Manufacturer's Specifications

FM Tuner Section

Usable Sensitivity: Mono, 12 dBf; stereo, 17.23 dBf.

50-dB Quieting Sensitivity: Mono, 21.45 dBf; stereo, 39.17 dBf.

S/N Ratio: Mono, 70 dB; stereo, 65 dB. THD: Mono, 0.2%; stereo, 0.4%.

Frequency Response: 20 Hz to 15 kHz, ± 1.0 dB.

Alternate-Channel Selectivity: 70 dB. Capture Ratio: 1.5 dB.

Image Rejection: 85 dB. I.f. Rejection: 90 dB.

Spurious Response Rejection: 90 dB. AM Suppression: 55 dB.

Channel Separation: 45 dB at 1 kHz.

Pilot Suppression: 60 dB. SCA Rejection: 60 dB.

AM Tuner Section

Usable Sensitivity: 400 µV/m.

S/N Ratio: 45 dB. Selectivity: 40 dB.

Image Rejection: 50 dB.

I.f. Rejection: 40 dB.

Amp and Preamp Sections

Outputs Power: 100 watts/channel, 20 Hz to 20 kHz, 8-ohm loads.

Rated THD: 0.009%.

Dynamic Headroom: 2.0 dB.

SMPTE IM: 0.009%.

Frequency Response: Phono, RIAA ±0.5 dB; high level, 10 Hz to 40 kHz, +0,-1.0 dB.

Input Sensitivity: MM phono, 2.5 mV; MC phono, 250 µV; high level, 150 mV.

Phono Overload: MM phono, 75 mV; MC phono, 6 mV.

S/N Ratio: MM phono, 80 dB; MC phono, 60 dB; high level, 95 dB.

Headphone Output Level: 420 mV into 8 ohms.

Tone Control Range: Bass, ± 10 dB at 100 Hz; treble, ± 10 dB at 10 kHz.

Subsonic Filter Response: 6 dB per octave, 30-Hz cutoff.

Loudness Control Action: +10 dB at 100 Hz (volume control set at -30 dB).

Channel Separation: 55 dB at 1 kHz, all inputs.

General Specifications

Power Consumption: 250 watts.

Dimensions: 16 1/2 in. (42 cm) W x 5 3/8 in. (13.7 cm) H x 14-15/16 in. (38 cm) D.

Weight: 27.3 lbs. (12.4 kg).

Price: $599.95.

Company Address: 1200 West Artesia Blvd., Compton, Cal. 90220, USA.

Though it isn't obvious from looking at the front panel, the ULTRX R100 receiver is a product of the well-known Sanyo Corporation, and here we should distinguish between American Sanyo and Japanese Sanyo. The former owns the ULTRX brand name and is, itself, owned by Japanese Sanyo, which also owns the Fisher brand. In this country and with many types of products, Sanyo and Fisher compete on head-to-head terms, but ULTRX is an upscale move by Sanyo to a more exclusive market, where Fisher existed even prior to its sale to Sanyo. Thus, what exists in the U.S. between Sanyo, Fisher, and now ULTRX is more nearly a case of sibling rivalry than anything else.

Be the marketing questions as they may, the R100 has a tremendous number of features going for it. Its PLL frequency-synthesized tuner section provides 20 station-memory presets and tuning, as well as an automatic station-search system. Major control functions are performed electronically, using rocker switches for varying volume, channel-balance, and bass and treble settings. A stereo synthesizing circuit can liven up such mono program sources as VCR and TV sound. A full encode/decode dbx circuit has been included, as has a DNR (Dynamic Noise Reduction) single-ended dynamic filter for reducing hiss and noise when listening to noisy program sources. There are inputs for two tape decks, with provisions for dubbing in either direction.

Even more noteworthy is an infrared remote-control module which performs the basic functions of volume adjustment, up and down tuning, and selection of the preset station frequencies.

The front panel, which gives excellent access to all these features, is itself a model of good, contemporary design. It has no protruding knobs, and its colorful displays, indicators and graphics make operation easy, even for the audio neophyte. However attractive and useful these features might be, they should be evaluated after the basic performance is considered. And when turning to measured performance versus specification, in light of the competition, the ULTRX R100 does pretty well for itself. I should mention at this point that two samples of the R100 were tested; the first unit, which I discovered later was a preproduction sample, did meet specification, while the second and full-production unit did better and is reported on here.

Control Layout

Along the lower edge of the front panel are a power on/off button; a stereo headphone jack; speaker-selector buttons; an FM i.f. bandwidth-selector switch; dbx encode and decode buttons; pairs of buttons for bass, treble, and channel balance; a subsonic filter switch; a mono/stereo switch; a loudness control button, and three "Tape Copy" buttons.

The center section of the panel contains the "Up" and "Down" tuning bars, an "Auto/Manual" tuning selector button, 10 preset tuning buttons (each accesses either of two memorized frequencies with the aid of an additional button labeled "1-10/11-20" that works like a typewriter or computer shift key), an AM/FM selector button, tape monitor switches, program-selector buttons ("Tuner," "CD," "TVNCR," "AUX," and moving-magnet and moving-coil phono), volume "Up" and "Down" buttons, and stereo synthesizing and DNR switches.

The entire upper section of the front panel is dedicated to a host of displays and indicating lights. Station preset number (from 1 to 20), selected AM or FM frequency, status of the volume control (in numerical indications from 1 to 10), and signal strength (in numbered, graphic symbols from 1 to 5) are all augmented by more than a dozen alphanumeric displays as well as graphic displays which show the status of the tone and balance controls, selected program source, and instantaneous power-output levels. The power-output meters take the form of a pair of ascending ramps of fluorescent graphics, one rising to the left, the other to the right. No actual bells and whistles, but there are plenty of flashing lights!

The rear panel of the ULTRX R100 is considerably less flamboyant. There are the usual pairs of inputs and tape-output jacks, two complete sets of spring-loaded speaker terminals, a pair of a.c. convenience outlets (one switched, the other unswitched), and a pivotable AM loop (which comes packaged separately, is snapped into place, and is then connected to the AM antenna terminals). For connection of an FM antenna, 300and 75-ohm coaxial terminals are provided. There are also a pair of screwdriver adjustments for tape-related uses of the dbx circuitry and a second pair for adjusting playback of dbx-encoded discs.

The owner's manual correctly states that, with most tape decks, the factory settings of these adjustments will work nicely, outlining a simple procedure for readjustment if you happen to own the "exceptional" tape deck that isn't tracking properly.

Tuner Measurements

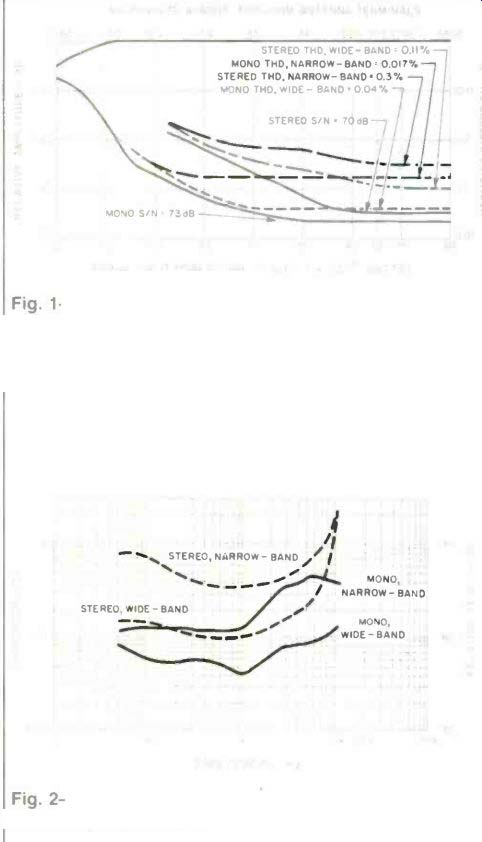

Usable sensitivity of the FM tuner section, in mono, measured 12 dBf, exactly as claimed. In stereo, however, usable sensitivity was determined by the muting threshold (muting is defeated only in the mono mode), which was set at about 22 dBf. The 50-dB quieting point occurred in mono with an input level of 16 dBf; in stereo, it took 37 dBf to reach that level of quieting. Although quieting characteristics were virtually the same in both the wide and narrow i.f. modes, distortion was, of course, markedly higher in the narrow-band mode than in the wide. This trade-off must be made to improve selectivity when interference from adjacent--or alternate--channel signals makes it impossible to listen to FM in the low-distortion, wide-band mode. THD for a 1-kHz, 100%-modulated FM signal at 65-dBf input level was only 0.04% in mono when the wide-band i.f. setting was used; in stereo, under the same conditions, THD was 0.11%. Both of these figures are much better than the manufacturer's published specifications. In the narrow i.f. mode, THD increased to 0.17% in mono and 0.3% in stereo, still well below published specs. Quieting and THD as a function of r.f. input-signal strength is shown in Fig. 1, while Fig. 2 shows how distortion varies with frequency in mono and stereo and in the narrow and wide-band i.f. modes.

Signal-to-noise performance was a bit disappointing to me, however, measuring only 73 dB in mono and 70 dB in stereo. I realize that these results do slightly surpass the published figures, but these days, I just expect that tuners and tuner sections of receivers will be able to do somewhat better than that.

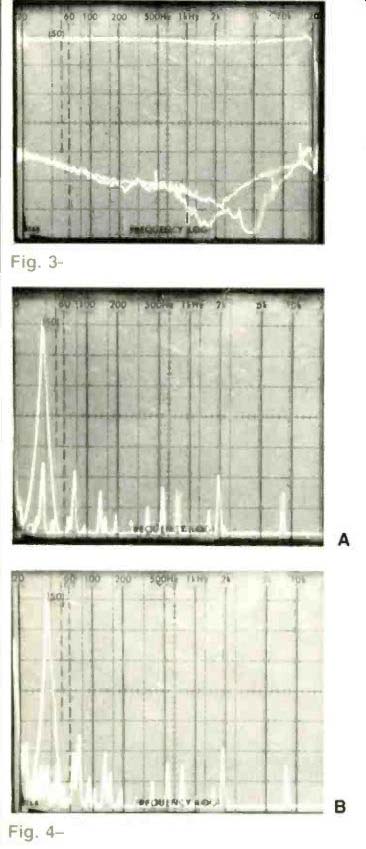

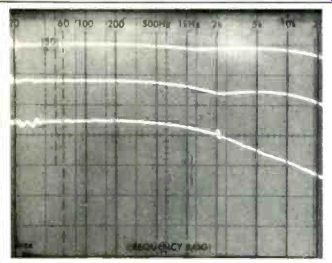

Frequency response deviated from flat by no more than ±0.6 dB from 30-iz to 10 kHz but exhibited a slight rise (2.1 dB) at 15 kHz. This was caused, no doubt, by less than perfect termination of the multiplex decoder's low-pass filter. Stereo frequency response and separation in the narrow and wide i.f. modes are shown in Fig. 3. Notice that separation didn't change much when switching from the wide to narrow i.f. mode; only the frequency of maximum separation shifted slightly. In the narrow mode I measured separations of 45, 40.5, and 36 dB at 1 kHz, 100 Hz, and 10 kHz respectively. Switching to the wide i.f. mode, separation measured 48, 43, and 39 dB for the same test frequencies.

Fig. 1-Mono and stereo quieting and distortion characteristics, FM section.

Fig. 2-THD vs. frequency, FM section.

Fig. 3-FM stereo frequency response (upper trace) and separation in narrow

and wide i.f. modes (lower traces).

Fig. 4-Crosstalk and distortion products resulting from 5-kHz modulation in one channel, as seen at opposite channel's output. Results here were almost identical between tests made in wide i.f. mode (A) and narrow i.f. mode (B).

Figures 4A and 4B show what comes out of the right-channel output of the tuner section when the left channel is modulated 100% by a 5-kHz test signal. In both 'scope photos, the tall spike at the left is the desired 5-kHz signal, while the signal contained within it is the 5-kHz component observed at the opposite channel's output. Additional signals to the right represent other undesired crosstalk and distortion components. Strangely, though the crosstalk components had about the same amplitude whether measured in the wide or narrow i.f. mode, tie 5-kHz separation was actually better in the narrow mode then it was in the wide. At first glance this seems unusual, until you look back at Fig. 3 and realize that 5 kHz happens to be the point of best separation for the narrow i.f. mode. At all other frequencies, there is the expected slight deterioration of separation as you switch from wide to narrow.

SCA rejection was a rather poor 58 dB. This means that, if there are FM stations in your area that broadcast an SCA subcarrier (either for private subscriber background music, data transmission, or any of the many other purposes now permitted by FCC rules), you may very well hear faint "swishing" sounds during quiet passages of music. Don't blame these on multipath problems. More likely, what you are hearing is crosstalk from an SCA subcarrier used by the offending station.

Figure 5 shows the frequency response of the AM tuner section, which was about what I have come to expect in most stereo receivers. There wasn't much output above 3 kHz or below 50 Hz.

Fig. 5-Frequency response, AM tuner section.

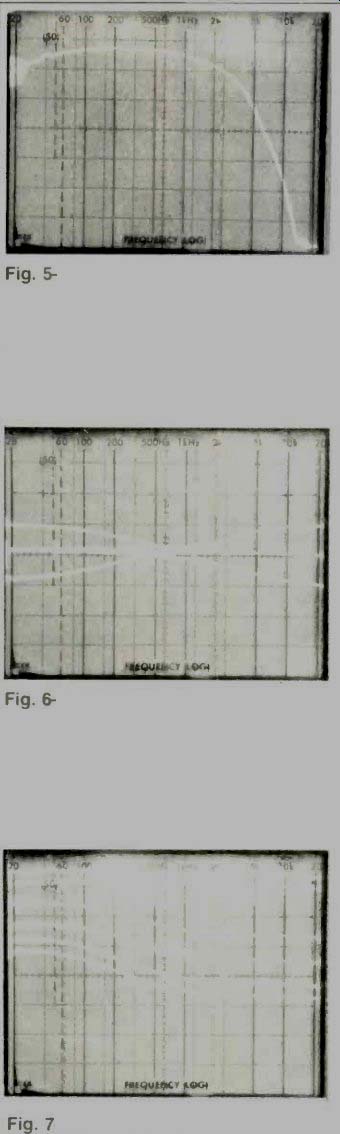

Fig. 6-Range of bass and treble controls.

Fig. 7-Loudness-control response at various settings of volume control.

Fig. 8-Response sweeps made at low signal levels to demonstrate action of

the dynamic low-pass filter system used in the DNR circuit.

Amplifier Measurements

Using a 1-kHz test signal, the power amplifier section of the R100 more than realized its claimed power output at its rated distortion of 0.009%, measuring only 0.0046% at 1 kHz. It produced a bit more harmonic distortion at the audio frequency extremes: 0.0065% at 20 Hz and 0.0057% at 20 kHz, for 100 watts per channel into 8-ohm loads. The SMPTE-IM distortion was lower than claimed, measuring only 0.004% at rated power output. Damping factor measured 44 (referred to 8 ohms), and dynamic headroom measured 1.8 dB as against 2.0 dB claimed. CCIF IM was less than 0.0033%, while IHF IM was below 0.03%. Amplifier clipping, for a 1-kHz signal input, occurred when output levels reached 124 watts per channel.

Preamplifier Measurements

Input sensitivity for the phono inputs, referred to 1-watt output, was 0.25 mV for MM and 25 µV for MC. It took 15 mV of input at the high-level inputs (or at the tape inputs) to produce 1 watt of output with the volume adjusted to maximum. Phono frequency response deviated from RIAA by no more than ±0.7 dB. Phono overload via the MM inputs was 125 mV, considerably better than the published rating of 75 dB, which I would have considered inadequate. Using the MC inputs, overload occurred with an input level of 12 mV, twice the overload level claimed. Frequency response for the high-level inputs extended from 8 Hz to 42 kHz for the -3 dB cutoff. With the subsonic filter activated, response was down by 3 dB at 40 Hz, a bit higher in frequency than I would have liked and higher than the 30 Hz claimed by ULTRX. Signal-to-noise ratio in the MM phono setting was 75 dB referred to 5-mV input and 1-watt output. At the same referenced output level, and with 0.5-mV input, S/N for the MC inputs was 63 dB. Via the high-level inputs, using a 0.5V input and again referred to 1-watt output, S/N was an undistinguished 73 dB, increasing to-88 dB of residual hum and noise when the volume was set to minimum.

Figure 6 shows the maximum boost and cut range of the bass and treble tone controls, while Fig. 7 shows the action of the loudness-compensation circuitry at various settings of the volume control. Notice that this particular loudness circuit affects only the bass frequencies; no treble boost is introduced even at low listening levels.

In Fig. 8 I have tried to show how the DNR circuit works. Using relatively low-level signals, I swept from 20 Hz to 20 kHz with my spectrum analyzer. DNR, as its full name implies, is a Dynamic Noise Reduction circuit; it can also be described as a dynamic low-pass filter. That is, when there is an abundance of high-frequency musical information in the input signal, the filter "opens up" and passes all audio frequencies. When only low-level, high-frequency information is present, the system looks upon this as "noise" or hiss, and closes down or attenuates the highs. As you can see in Fig. 8, by applying a very low-level sweep (lowest of the three traces), I "tricked" the circuit into believing that the "highs" in the sweep were really noise, and so it attenuated them. At a slightly higher level, the circuit wasn't quite sure whether it was seeing noise or musical highs, and so it let the highs through with only slight attenuation. At still higher levels, the circuit was certain that it was dealing with "musical" treble tones, and passed them on with virtually no attenuation.

Use and Listening Tests

Sometimes, trying to cram too many features and making them overly user-friendly carries with it certain disadvantages. When using the ULTRX R100 for entertainment and musical listening purposes, I was bothered by at least three things that are a direct result of all the electronically adjusted parameters of this receiver. The electronically adjusted volume control works in discrete steps. Normally, that would be fine (I've gotten used to step-detented mechanical volume controls that do the same thing); in this case, each step is accompanied by a slight popping sound from the speakers. No doubt FET or other solid-state switches are being used to change the volume level, and they introduce noise and pops during the adjustment process. I found that the bass and treble controls, as well as the balance control, which also operate in electronically controlled steps, seemed to take forever to get where I wanted them to. I have nothing against rocker switches and pushbuttons, as they sure make a front panel look sleek and elegant. But every now and again, I yearn for the days when a simple, smooth twist of a rotary knob brought me to the exact control setting I wanted in less than 1 S. Once I got all the adjustments out of the way, the tuner, preamplifier and amplifier sections worked adequately well and sounded good enough to justify the price of this receiver. All the extra displays, of course, are needed to tell you what a marker dot on a knob could have told you at less cost. However, I have no real objection to their use, since, on a sound quality versus price basis, the R100 is a winner.

Whether its price would have been lower without all those front-panel displays is, I suppose, moot. On the very positive side, there are all too few receivers that offer built-in dbx as well as DNR noise reduction, and I must say that both of these circuits worked extremely well. As ULTRX points out in one of their advertisements, with so many of us getting used to noise-free reproduction from digital program sources, we tend to get spoiled and want our older, analog program sources to be just as free of noise. The dbx NR system is one way to accomplish this for the tapes you record, not to mention that it allows you to record much greater dynamic range than would otherwise be possible. By the same token, DNR helps out older program sources as well as noisy FM broadcasts whose background noise can't easily be eliminated in any other way.

I haven't mentioned the stereo synthesizing circuit (ULTRX calls it a stereo matrix) simply because I regard such circuits as poor substitutes for the real thing. I suppose, though, if you are piping video sound into this receiver and if that program source (whether from a TV broadcast or a VCR) is in mono, there's some sonic excitement to be derived from the quasi-stereo effect of the ULTRX circuit. If you don't like it, you can always switch it off and go back to mono-I did.

The extra high-level inputs on the R100, over and above the usual AUX inputs, were most welcome. These days, most people have more and more program sources to hitch up to their central audio components, what with stereo TV on the way, CD players catching on and VCRs coming out with hi-fi sound. The ULTRX provides for all of these, with no need for external switchboxes or patch bays. It offers adequate power output for virtually any pair of speakers housed in any reasonable size of listening room. It picks up all of the FM stations I would expect it to, and makes it easy to access up to 20 stations at the touch of a button. In short, the ULTRX R100 is a no-nonsense receiver on the inside, notwithstanding some of its front-panel flash on the outside.

-Leonard Feldman

=================

(Adapted from Audio magazine, Apr. 1985)

Also see:

Technics SA-424 FM/AM Stereo Receiver (Equip. Profile, Aug. 1981)

Link | --Technics by Panasonic SA-8000X 4-Channel/2-Channel Receiver (Equip. Profile, Nov. 1974)

= = = =