by IVAN BERGER and HANS FANTEL

This article is adapted from a chapter of The New Sound of Stereo, a new book by Audio's Technical Editor, Ivan Berger, and Hans Fantel, syndicated audio columnist for The New York Times. The book will be published in February 1986 by Plume, a division of New American Library. 01985, Ivan Berger and Hans Fantel.

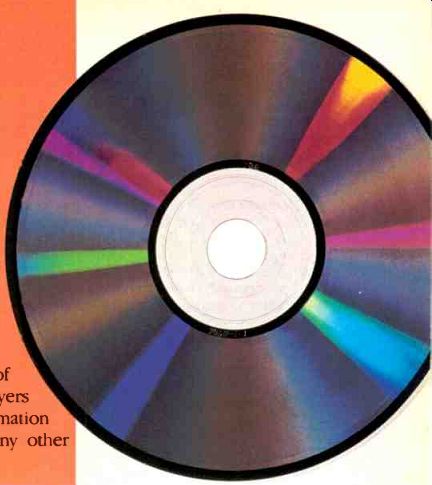

While more and more new phonograph records and cassettes are made from digitally recorded master tapes, these records and tapes are analog recordings which is why they're playable on ordinary turntables and tape decks. The one purely digital system commonly available for home use is the Compact Disc or "CD." The CD itself is a rainbow-silvered disc of plastic only 4.7 inches in diameter-smaller than a 45-rpm "single" record. It's not played by dragging a needle along a groove but by reading its information with the pure light of a laser beam. Because light beams cause no friction, the disc won't wear out or deteriorate no matter how often you play it. It yields better sound than even a brand-new LP or tape, and far, far better sound than tapes and records that have been played a lot. Be sides, the Compact Disc is the most convenient and efficient sound-storage medium ever devised.

It's also a most unusual medium. Physically, the only things that CDs and LPs have in common is their shape. The information recorded on a CD is not engraved on its surface, but sandwiched between an upper layer of lacquer, on which the label is printed, and a layer of tough, transparent plastic which forms the bottom of the disc, and through which the player's laser reads the information. The laser is not guided by a physical groove, the way a phonograph stylus is, but by a computer-operated servo mechanism that analyzes the data coming off the disc.

The servo senses when the laser is beginning to mistrack, and adjusts the laser's aim accordingly.

While you can see an LP record's grooves, the CD's signal path is too fine to be directly visible, except under very high magnification. A CD has more than 15,000 information lines per inch, about 60 times as fine as LP grooves. Uncoiled, a CD's signal path would stretch about three miles, versus about a quarter of a mile for an LP's groove. The LP turns at a constant speed (33 1/3 rpm), which means its in formation density varies, spread out at the longer, outside groves and densely packed at the smaller, inside ones. The CD's rotational speed varies, from 500 rpm at its innermost diameter to 200 rpm at its rim, to keep the information density as uniformly high as possible.

(Incidentally, a CD track begins at the center and spirals out to the rim, just the opposite of LP practice.) And since the CD is a true, digital medium, the information it carries is not the LP's continuously varying groove but a stream of ones and zeroes, rep resented on the disc by tiny pits that cause minute variations in the reflections from the laser beam.

What's on the Discs

Thousands of CDs are now available, something for every imaginable taste. This sounds like a lot, but it's actually just a drop in the bucket compared to the number of LP records (more than 50,000) or prerecorded cassettes available. A glance into any record store will show you that-but then, cassette has a head start of some 20 years, and LPs have been around even longer. Even so, the number of available CDs is growing fast, and virtually every record company you've ever heard of now offers at least some.

The Compact Disc has become an international standard. That's partially because the audio industry was smart enough, for once, to pile onto a single bandwagon. But the CD's success is due even more to its convenience, durability, and sonic excellence.

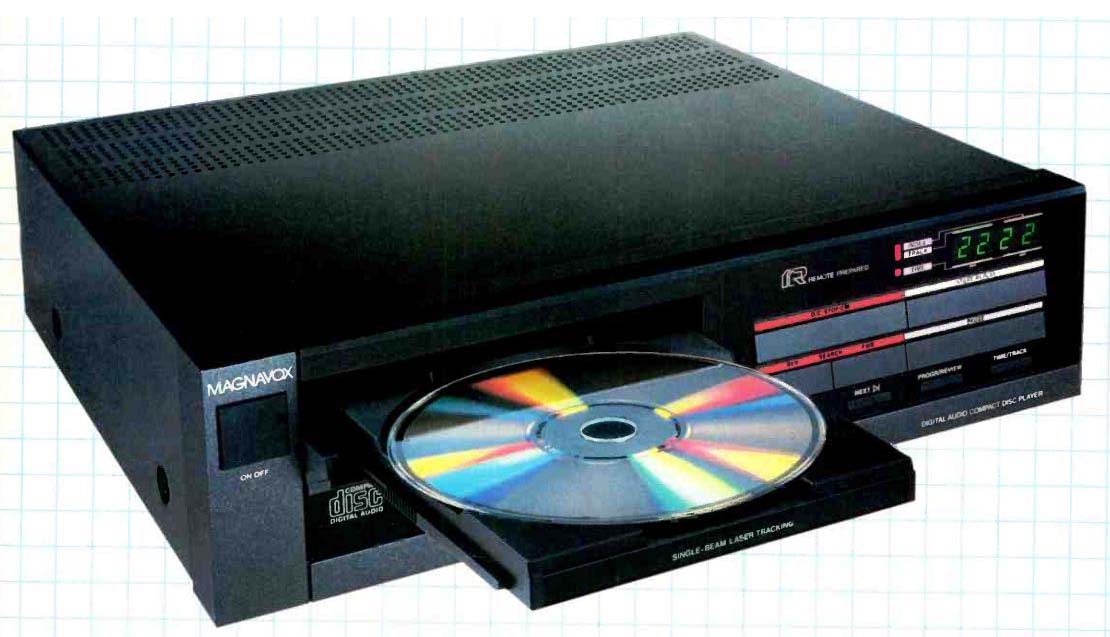

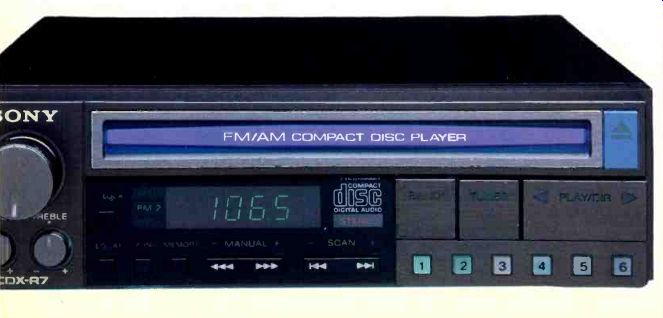

------- Less than three years ago, there were no consumer CD players. Now

there are units for the car, like this Sony, as well as players for home

and portable use.

CD's Convenience

Convenience starts with the CD's small size. This not only saves storage space, but opens up new uses that LPs couldn't touch, such as portable players to hang over your shoulder or in-dash players for the car. (The size of a car's dashboard radio slot was one of the factors considered when the CD's size was set.) The disc is recorded only on one side, so you don't have to flip it over halfway through.

A CD can hold nearly 75 minutes of music, enough for long works such as Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. For longer works, such as operas, the convenience grows: Three CDs can hold as much music as five LPs, and those three CDs require only two interruptions to change discs, while ten LP sides require nine interruptions.

Compact Discs still cost more than LPs, though the price gap between them is shrinking. Works which use the CD's full capacity (such as Beethoven's Ninth) already cost less than the same music would on LP.

The CD system was designed for automation, adding still more to its convenience. All CD players are automatic, to varying degrees-more like cassette decks than phonographs in how they work and look. That automation starts with disc loading and play.

You push a button to open the disc compartment, place the disc inside, and close the compartment again. De pending on which button you pushed to close it, the player will either start playing the disc at once or wait for you to tell it which tracks on the disc you want to hear or to skip. Many players even let you program those tracks into whatever sequence you please. (It's not like programming a computer; you just key in the numbers of the tracks you want, and the player takes it from there.)

If you want to listen to a track again, just push a button-ditto if you want to jump ahead to the start of the next track or back to the beginning of the previous one. Many Compact Disc players have audible search, which lets you zip ahead or back at a high rate while still hearing the music speeded up (about three to ten times normal) but at correct pitch. This feature helps locate specific passages you want to hear. A growing number of players can also be set to play the first few seconds of each track, or of each programmed track, so you can find the one you want even if you don't recognize its name.

There are repeat functions, too. De pending on the player, you can repeat the entire disc, repeat the tracks you've programmed, repeat any single track, or repeat a section of a track that you've marked in the player's memory.

Many cassette recorders also do these things. But tape players take longer to do them because they have to search all along the tape for the selections you want. A CD player just consults a computerized table of con tents at the start of the disc once, memorizes it, and then zips across the disc (a basic advantage of the disc shape over tape) to any track you want. Tape's audible cue and review functions are slowed down still further, to minimize the screech you hear when listening to a speeded-up tape something that's avoided with a speeded-up CD.

--- A single CD can hold over an hour of music, while CD players offer

a level of automation not possible with any other program source.

Besides, tapes hold only audio information; CDs hold that and a good deal more. For example, since the tracks on classical CDs tend to be fairly long, some have index points coded where significant passages start within a track; an opera, for example, might have one track per act, but index marks for every scene or aria. Some players let you go straight to any of these indexed points, just as you can to the beginning of a track, simply by keying in its number and pushing a "go" button. Not all discs are indexed, however.

There's also room on the disc for other codes, as yet unused. Future CDs (and we're only talking a year or three Into the future) may use the information space for song titles, sing-along lyrics, opera librettos, song translations, or even a series of still pictures, to be displayed by the player itself or on your TV screen. Some CD players already have output jacks for this purpose. And, as yet another link between CD and the TV screen, there are already players which use one la ser to play both CDs and LaserVision videodiscs.

CD players also have displays to tell you what they're doing. The more ex pensive the player, by and large, the more elaborate and informative the display. Lower priced models may tell you only which track is currently playing. Others may tell you how many tracks are on the disc, how long they are, how long the entire disc is, how much playing time has elapsed since the beginning of the disc or the current track, and how much remains-all helpful when taping. The display may also indicate what selections you've programmed for play and how many are left.

Some players show on their displays how all their switches are set, so you can read all operating information in one place. Other players put little lights on each switch, which makes that in formation easier to read from across the room.

Players also differ in the number of selections you can program them to play automatically, ranging from none to 99. On multi-disc, automatic CD changers, which are still rare, you can program in the disc as well as the track number. With just a minute or so of button-pushing, this allows you to set up a whole evening's listening.

This hardly exhausts the list of CD conveniences. Most of the more ex pensive players have remote control; some even share a single remote-control unit with other audio or video components from the same manufacturer.

A few players have pitch controls, which raise or lower the recording's pitch to match yours, if you want to play or sing along with the disc. Unlike the pitch controls on some turntables and tape decks, the ones on CD players don't change the tempo when they change the pitch.

Like most tape decks, some CD players have timer start switches, which start play as soon as power is fed to the unit. With this and an external timer, you can program a player as a musical alarm clock-an expensive substitute for a clock radio, but at least you'll know exactly what music you'll hear when it switches on.

If you tape CDs for use in a car or portable cassette player, you may find them among the best-sounding tapes you own. Several player features are de signed to make such taping easier. Some have calibration-tone generators, which put out a tone at the same level as the strongest signal that could come from a CD. This will help you set your tape deck's level controls before recording.

A few also insert several seconds of silence between tracks so that a tape deck's music-search function will be able to sense the silent gap be tween musical selections and, hence, to find the start of each selection.

The auto-pause function found on some CD players serves several purposes. When you're taping individual selections from different CDs, it saves you from accidentally taping the track that comes after the one you want.

(Players which automatically stop after playing a single, programmed track are of equal help when taping.) The enforced pause also gives you a chance to decide what to listen to next if you don't want to program several cuts at once. If the music is deeply arresting, it also lets you stop and con template what you've just heard, instead of dashing merrily on to the next selection.

At least one player now has a built-in compressor, which can be used to narrow the dynamic range between the loudest and softest signals on a CD.

This lets you record a CD with a wide dynamic range onto tape, whose range is narrower. It also keeps the sound from becoming too dramatic for quiet listening. This is especially useful when making tapes for use in the car, where road noise often drowns out qui et passages. Future CD players may also have expander circuits, to make the swings between loud and soft more dramatic if you feel a performance is too tame.

If recordings took full advantage of the CD's capability to reproduce the full dynamic range of a live performance, there'd be no need for an ex pander. But few CDs do use the entire range available, partly so they'll stay listenable under home (as opposed to concert-hall) conditions, but also be cause they're often made from the same basic master tapes as LPs are, to simplify life for the record companies. As CDs account for more of their business, record companies are be ginning to produce separate, wider range master tapes for the digital medium. At that point we'll need compressors, for times when our homes are noisy or we're not listening with full attention.

We've described these features in general terms because different manufacturers give them different names.

The more features a CD player has, the more convenient it becomes to use up to the point where the number of buttons and display indicators over whelms you. Even then, careful design can make the player's controls easier to understand.

Your tastes and circumstances govern which features you'll want. For ex ample, programmability means more to pop-music listeners, whose discs contain many short songs of unequal quality; classical-music listeners tend to listen to a disc from beginning to end. Remote control is helpful if your system's components are far from your listening chair, but not much use if you can reach the front-panel controls from where you sit. Players which load from the front can be stacked under other components, while top-loading players may be more convenient if they're placed on a low cabinet or table.

CD Durability

A CD is a lot less vulnerable to damage than an LP. It's made of harder plastic, and the recorded information is not on the disc's surface, but inside, where the transparent plastic shields it from harm.

That's possible because nothing touches the actual recording. The laser merely looks at it. The beam focuses on the recorded inner layer, and an optical system reads the light reflection, which represents the binary code.

The plastic of the disc material is actually part o' the optical system, narrowing the laser spot as it passes from the disc's surface down to the recorded layer. As a result, all but the worst dirt and scratches are far enough out of focus to be invisible to the player's optical system. And since the disc's surface is glassy smooth, not grooved like an LP's, most dirt is easily wiped off with a clean, damp, soft cloth.

CDs aren't invulnerable, however. Although dirt wipes off the playing surface, scratches don't. Minor scratches usually won't affect play, but bad ones can cause distortion, add noise (usually a ticking sound) or make the laser skip or lose its place. Dents and scratches on the label side can be even more serious, because the information layer within the disc is protected only by a thin and fragile lacquer coating or the label side, as compared to the thick, tough plastic below the information layer. CD players can compensate for many problems caused by dirt or damage, but not all of them. It pays to pamper Compact Discs.

They're becoming less expensive, but they're still not cheap.

Do CD Players Sound Alike?

There are differences between the sound of different CD players. But those differences are very subtle-so much so, in fact, that even experts have trouble hearing them. What differences there are stem mainly from the players' filtering method, their error-correction circuitry, and their analog output sections.

When a digital signal is turned from a hail of numbers to a stream of sound, ultrasonic frequencies creep in: they are not audible but can cause audible problems. These frequencies must be filtered out. Filtering them from the analog output signal takes complex filters (sometimes called brick-wall filters, be cause of their sharp attenuation of the undesired frequencies), which affect the phase response of the sound. If some of those frequencies are filtered from the digital signal first, very mild analog filters can then finish the job.

Many expert listeners feel that this technique, of using digital filters together with analog filters, improves the sound. Where analog systems try vainly to eliminate errors such as noise and distortion, and then hope for the best, digital systems acknowledge that errors will occur and take steps to limit their effect. Minor errors can be completely corrected, and those that are too large to be corrected can be "concealed," with the player computing and filling in approximately what the correct signal should be. The better the player, the less it errs in reading data from the disc, the more errors it can correct, and the fewer it has to conceal. Unfortunately, there are no specifications for this, so error-handling ability must be inferred from test reports which tell how well the player can handle special "obstacle course" test discs, and from whatever differences you can hear when comparing players to each other.

After the digital data has been read, error-corrected and converted into analog form, the signal must go through ordinary analog circuits in the player's output section. Some player manufacturers lavish attention on these circuits, while others throw in just enough cheap parts to do the job. This, too, can subtly affect sound quality.

CD Tomorrow--and Beyond

In a few years, you may even be able to record CDs at home, as easily as you now record tapes. The first recordable CDs may be "write once" discs that cannot be erased and re used, but discs that can be recorded, erased and reused should follow.

Recordable discs will probably en courage the use of the CD as a storage medium for computer data and pro grams. That could begin before the medium becomes recordable; a standard computer format, CD-ROM, al ready exists. Yet a CD-ROM holds so much that there are few programs or data bases (other than an encyclopedia or two) that can fill it without waste.

But you can already record digital sound at home-though on tape, not disc. Even before CD arrived, there were PCM processors, which used videocassette recorders to record studio-quality digital sound, and a few complete PCM recorders using video cassette tapes. Coming soon will be digital recorders using small tape cassettes, about two-thirds the size of to day's regular cassette tapes.

(Audio magazine, Apr. 1986)

Also see:

Living With CDs (Apr. 1986, CD)

= = = =