By ROBERT ANGUS

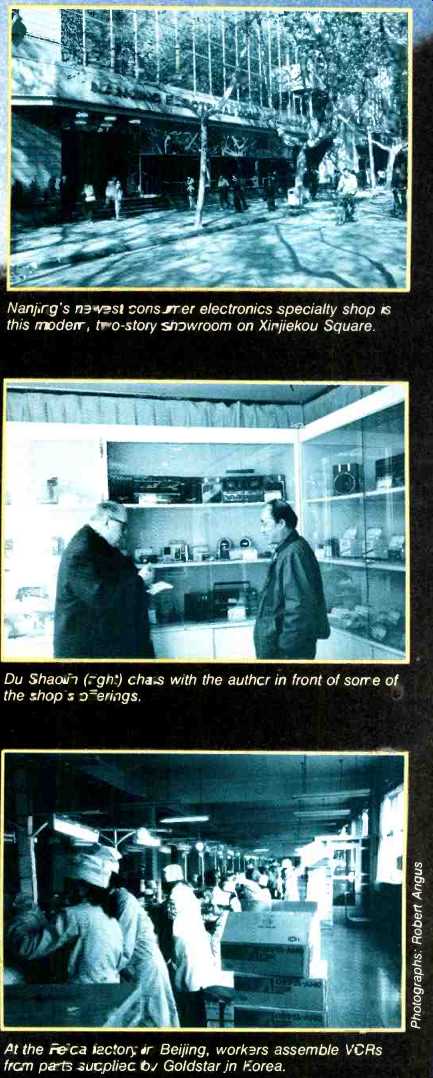

Xinjiekou Square is one of the busiest in Nanjing, particularly on a Sunday, when most Chinese have the time to shop. Just off it, within a few hundred yards of one another, stand three large, new consumer electronics shops, all owned by the state and locked in fierce competition with each other. At almost any time during the business day, you'll find audiophiles shuttling back and forth among these shops in search of the right loudspeaker or the best price on a power amplifier.

That's right. Audiophiles. In China.

Nobody's sure just how many of China's one billion people are dyed-in-the-wool sound perfectionists, but there are enough to make consumer electronics, in general, and audio, in particular, a growth industry and for State-owned industries like Panda, Peony, and Feida to pay attention. Just ask Du Shaolin, Li Jun, Yang He Ming, or Yao Hong. Du manages the Nanjing Electric Home Appliances store just off Xinjiekou Square, a sort of Oriental " Circuit City." This shop caters to electronics hobbyists and experimenters as well as offering a more prosaic selection of stereo music centers, color TV sets, VCRs, refrigerators, and electric ranges. Mme. Li edi’s Radio, China's largest (900,000 circulation) monthly magazine for electronics enthusiasts, while Yang is vice president of the China Audio Industry Association and director of the Shanghai Tape Recording Equipment Factory. Yao is typical of China's fast-growing yuppie class--a young professional fiercely proud of the component A/V system he assembled himself Yao, who has a relative living in Hong Kong, received his first stereo system five years ago, when he got married. It was, in fact, the center piece among the wedding gifts, re placing more traditional presents such as furniture and bedding. The system cost about $1,000--roughly 20 months' income for a typical Chinese worker. It consisted of two giant three way loudspeaker systems (brought up, one at a time, on the Saturday train from Hong Kong to Guangzhou), a Chinese-made Feida AM receiver (10 watts per channel, he recalls proudly), a domestic Panda dual-well cassette deck, and a turntable made for professional use in Shanghai. FM simply isn't available in China, but Yao claims that the quality of mono-only AM broad casting is quite good.

above:

--Nanjing’s newest consumer electronics specialty shop is this modern, two-story showroom on Xinjiekou Square.

--Du Shaoii (right) chats with the author in front of some of the shop’s offerings.

--At the Feida factory in Beijing, workers assemble VCRs from parts supplied from Goldstar in Korea.

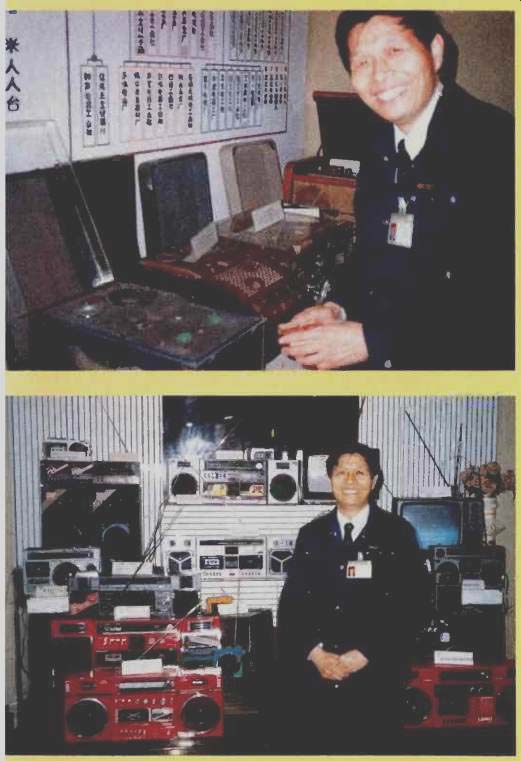

top: Yang He Ming, director of the Shanghai Tape Recording Equipment

Factory, poses with China's first wire recorder, made by the factory in 1951

(far left). Next to it are three open-reel machines produced by the factory

from 1953 to 1973. The second and third machines from the left were designed

to use paper-based tape. (above) Yang with his factory's current, more up-to-date

product line.

Manufacturer Yang says that to understand the Chinese audiophile, it helps to have a background in 20th-century Chinese history. As recently as 1928, China was still ruled by feudal warlords. Six years later, while Europe and the Americas struggled to climb out of the Great Depression, China's Civil War started with Mao Zedong's Long March to the North, which was interrupted by the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. The Civil War resumed with a vengeance at the conclusion of World War II in 1945, culminating in the expulsion of the forces of Chiang Kai-shek in 1949. At just about this time, hi-fi was developing as a hobby for music lovers and do-it-yourselfers in the United States.

In 1951, Yang's factory made China's first wire recorder--for broadcast use--after reading about them in Western magazines like Audio. "You must remember that we were completely cut off from technical information from the West at the time, and we had to rely on information in the popular press," he recalled recently. Beginning in 1952, the government not only forcibly collectivized China's struggling radio and television factories but took over the distribution and sale of all consumer products, replacing privately owned shops with ones owned by the state. Although it was government policy, at the time, to provide the people with radios and television sets, these were supplied first to community centers and trade unions rather than consumers. Viewed as part of the state communications network, basic radios were considered essential products- niceties like music-reproduction systems for the home were not.

During the Great Leap Forward, which lasted from 1958 to 1960, professionals (including engineers) were repatriated to the countryside in an attempt to force the pace of development by substituting manual labor for technological progress. Although in 1953 Yang's factory began making tape recorders-designed for paper-backed, quarter-inch tape--it continued to produce wire recorders for the government until 1958. It wasn't until 1960 that acetate and polyester re placed paper-a bare three years be fore the introduction of the Compact Cassette in the West.

Yang and his factory are proud of these early products, maintaining a museum where they are displayed. Interestingly, my photo of Yang with the collection was the only one I shot on my entire Chinese tour which caused any controversy. I simply asked Yang if he would pose with the wire recorder.

Following the translation, there was a feverish and heated discussion among his colleagues. As I tried to take the picture, I had camera trouble. Another heated discussion. Yang then volunteered the services of one of his colleagues--the most vociferous one--to see what was wrong with the camera.

Nothing was, as it happened, and I took the picture. Then the translator asked me to take another, showing Yang and his current line of boom-boxes and personal portables, which I did. Outside, the translator explained that while Yang had no objection to the picture, his colleagues were concerned that he and the factory might be subject to ridicule because of the primitive equipment. I assured her that I had no intention of embarrassing either Yang or the factory and that the story of how the recorder came into being was of immense interest in the West, as was historic equipment of this type. (In fact, since I'm a collector, these historical gems made my mouth water!) The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, a period which saw political turbulence at home and attempts to spread revolution abroad, lasted from 1965 to 1968. Beginning with the death of Mao in 1976, a power struggle for leadership was followed by a purge of Maoist elements. Toward the end of the decade, China was actively seeking better trade and cultural relations with the West, and in 1980, the government encouraged factories to begin producing more consumer goods. In mid-1987, restrictions on so-called private and individual businesses were relaxed, permitting citizens to open their own shops, provide services, and even employ others. Since then, ac cording to the official newspaper, China Daily, the economy has created a large new class of millionaires (in yuan; translated, that's $275,000-aires).

Nobody really knows how audiophilia got started in China, or exactly when. Mme. Li says that her magazine has been publishing do-it-yourself projects, including the construction of loudspeaker systems and amplifiers, since the late 1950s. Retailer Du re calls that kids and experimenters have been scouring electronics shops for parts ever since he can remember. "In the early days," Yang recalls, "being an audiophile required a great deal of time-not so much to construct a project as to find the parts for it. You might have visited every electronics shop, department store, and repair shop in your city to find what you needed.

Even then, it might have taken trips to two or three different cities to find everything." People did build amplifiers, tuners, and speaker systems from the circuit diagrams published in Radio or copied from equipment brought into China from abroad.

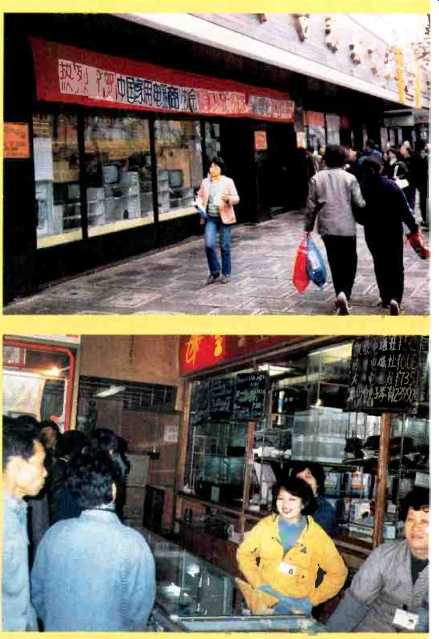

(top) Shanghai TV Store is one of the city's largest electronics specialty shops.

(above) Clerks at Shanghai TV Store's audio counter cope with mid-morning

crowds. Items on sale are listed and priced on the blackboard behind the counter.

After the easing of tensions with the Crown Colony of Hong Kong in the early 1980s, hi-fi took its own Great Leap Forward, particularly in the southern city of Guangzhou. During the height of the Cultural Revolution, hundreds of thousands of Chinese poured across the border to find work or sanctuary. By Chinese standards, they became well-to-do within a few years and began returning home on the Saturday afternoon train.

As is the Chinese custom, they returned with gifts--the kind of items not available in the People's Republic. The more elaborate the gift, the more prosperous the donor was deemed to be.

By the mid-'80s, that led to train travelers bent under the weight of gigantic loudspeaker systems, big-screen color TV receivers, VCRs, and just about every audio component and package available in Hong Kong. The trade became so lucrative that some Japanese manufacturers and Hong Kong retailers found it worthwhile to advertise in China to convince shoppers that only their brand or the products available in their shop were worth having.

Most of these gifts have become the centerpieces of households which usually embrace three generations, in homes which have no central heating and where warmth is provided by many layers of clothing. Some have turned up in flea markets and black markets and have found their way to cities farther north. As the products have spread northward, so has the prestige of owning a first-rate music system, particularly if one or more of the elements is imported.

One of the problems facing Chinese audiophiles is the shortage of software. There's no such thing as FM radio or broadcast stereo, and Compact Discs have yet to make any impact, for two reasons. There is no domestic supplier, although CD players are being manufactured for export. Further, the few titles available from Hong Kong or Japan are of limited interest and are unreasonably expensive. (If CDs were available, it's been estimated that they would cost the equivalent of one month's salary!) Vinyl records have all but disappeared from shops, replaced by audio cassettes, which generally are inexpensive and of acceptable quality--no Dolby noise reduction and no high-bias tape, but at least some very presentable recordings in terms of dynamic range, background noise levels, and frequency response. Actually, there are dozens, if not hundreds, of tape duplicators in China. These include the likes of back-street pirate operations (which survive on scrap tape and parts imported from Hong Kong), the current Chinese pop hits taped from Hong Kong radio, tapes from the Crown Colony, and tapes provided by the large state-owned plants which produce a bewildering array of programs. These programs include folk and Chinese classical music, talking books for the blind, and instruction- al tapes for students from preschool to postgraduate level.

Shops in the major cities are well stocked with blank audio and video cassettes. Locally made C-60 tapes sell for as little as 540, while Japanese-made TDK D60 and Maxell UR 60 cassettes cost $1.33 and serve as the country's premium audio tapes. It is said that in some southern cities, counterfeit and look-alike Japanese-brand cassettes (made in China and/or Hong Kong) are on sale for somewhat less, but I saw no evidence of them or of any cassette lengths other than C-60. Yang He Ming hopes, however, that China soon will be producing its own premium recording tape, either as part of a joint venture with a U.S. or Japanese company, or on its own.

According to Yang, some 280 factories are members of the China Audio Industry Association, competing with one another for retail outlets and customers. This helps to explain why Du Shaolin's shop offers different brands, products, and prices from its nearby competitors, although they are all owned and operated by the government. "All other things being equal," Du observes, "Chinese like to buy from local factories," which helps to explain the prominence of the local Panda brand in his showroom.

However, things are not always equal. Some brands have a reputation for offering better value, greater reliability, or better workmanship, just as in the West. Du says that if he has bad experiences with a brand or a particular product, he stops carrying it--usually after drawing the factory's attention to the problem. "Many times, they are able to correct it and we have no more trouble. But I can't afford to have customers complaining. If the factory can't or won't solve the problem? We'll turn to someone else to get what we need." Du has more clout with the factories than some of his competitors; he's also a wholesaler who supplies smaller shops with equipment.

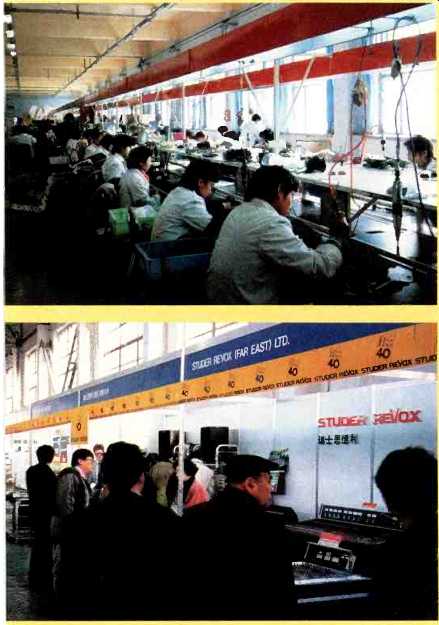

(top) Workers at Nanjing's. Panda factory assemble Sharp TV sets on one side

of the assembly line and Philips TV sets on the other. (above) Equipment from

all over the world was on view at Beijing's Second Annual International Audio-Visual

Show last December.

above: A scene at the Peony factory in Beijing, where VCRs, TV sets,

tape decks, and boomboxes are made.

The Yaos agree that, among domestic brands and products, they prefer to buy things made locally. But when it comes to serious purchases like audio and video equipment, there's a distinct preference for imports, even though they may cost twice as much as the domestic equivalent. According to Mme. Yao, there is a perception that imports are made better and will last longer, thus making them worth the extra money.

Du's shop has a parts department which caters to hobbyists and experimenters, but he believes that the great days of do-it-yourself audio are over, at least in Nanjing. "The quality of the factory-produced systems is very much better than it was a few years ago and represents much better value than any do-it-yourself project," Du claims. For enthusiasts who want separate preamps, power amps, and low boy two- and three-way loudspeaker systems, Du sells them but admits that packaged systems outsell components handily. One exception is the audio cassette deck, which upgrades older turntable-only systems. The most popular decks, he explains, are dual-well units which permit their owners to make copies of favorite recordings.

Mme. Li agrees, saying that her readers these days are more interested in new audio and video technology than in circuit diagrams. "Nobody has the time, anymore, to chase around from shop to shop to get the parts and then sit down and build an amplifier or loud speaker system-particularly when they can buy something that's just as good in a shop for less money." Although Du is free to choose the products he sells, there are strict government guidelines on how he con ducts his business. Every retail shop provides its customers with a three way guarantee on their purchases. The buyer is entitled to his money back within five days if he changes his mind or finds something wrong with the item-provided, of course, he hasn't damaged it. There is a factory guarantee that, for a reasonable period of time, the unit will be repaired or, if repair is not possible, exchanged. Finally, the shop itself guarantees that parts will be available for the life of the product. While Du's store maintains its own service department, a much larger state-run repair shop is just down the street. "We do the simple repairs here, but we don't have the parts or the manpower for more elaborate repairs," he adds. In addition to the state shop, there are also private repair shops.

These came into existence some years ago, as moonlighting operations run by technicians employed in the government-owned shops. The private repair shops charged more, but customers usually got their equipment back in a fraction of the time the state-owned shops took. There was some official criticism that the moonlighters were using tools and parts which belonged to their daytime employers, although the practice was allowed to continue be cause of the popularity of private re pair. When the government officially welcomed private enterprise in 1987, electronic technicians were among the first to begin hiring help-often their former colleagues. It's said that they are now among the nation's new "millionaire" class.

Also said to be bucking for such status are the peddlers--entrepreneurs who buy goods in the city where they're made (and consequently are inexpensive) and transport them to another (where they're either unavailable or very expensive). Factories in the southern cities of Guangzhou and Shenzhen are grinding out everything from cheap transistor radios and personal portables to semiprofessional audio gear. But in the cities of Kunming and Guiyang, less than 1,500 miles away, state-run stores can't keep the hottest audio items on their shelves. Enter the entrepreneurs, who aren't bound by the 15% markup government-owned shops are allowed. In alleys, the front rooms of homes, and increasingly in small shops, the peddlers offer a dazzling array of items at equally dazzling prices. There, a hobbyist can find a printed circuit board for an amp or VCR, as well as woofers, tweeters, crossovers, cassette decks, portable players, and the other accoutrements of Chinese audio. All this is in addition to articles of clothing, food stuffs not found in the state stores, and more. Acknowledging the importance to the economy of this growing class, China Daily recently reported that these private and individual business people "come mainly from those previously unemployed: Retired or resigned workers or technicians, farmers, and ex-criminals." The private shops have another edge over their state competitors: They are often open an hour earlier and stay open several hours later than their 9-to-5 competitors, to catch potential shoppers on the way to and from work.

Du notes that while he's allowed a maximum 15% to 18% markup on the products he buys from state-owned factories, he can charge what the traffic will bear when it comes to imported items, such as Sherwood car stereo and home components. He is also free to charge less than the authorized markup, to stimulate sales. "I love imports," Du says, claiming that by handling them, he performs an important market-research function for the factories. "We tried Compact Discs a while back, importing players and discs from Hong Kong. But they were too expensive-nobody bought. So t reported this to the factories. If CD players had proved more successful, one or more of the factories would be making them by now." A current experiment involves VCRs. Du's shop offers two Panasonic models, at $3,630 and $3,800. "We haven't sold any yet," Du says, "but we've had a lot of people looking at them." He remains hopeful that someone may yet purchase one of the VCRs. Du's status as a wholesaler allows him to import directly for his own shop, provided he has the hard currency to pay for the products he wants.

Du seemed genuinely surprised to learn that the Sherwood components he sells were not made in the United States--he has been marketing Sherwood as "the American brand." "We have also handled Ampex tape recorders from time to time," he added, "but we're not carrying them now because the price is too high." Some genuinely American equipment--as well as a great deal of European and Japanese gear--was on view in Beijing during my visit, at the Second Annual International Audio-Visual Show held last December. According to organizers for the six-day event, some 75,000 electronics hobbyists and consumers came to see a full range of do-it-yourself parts, audio and video components, and professional broadcast and video equipment, shown by 51 exhibitors. The Show even included the latest in high tech, such as Super-VHS VCRs and high-definition TV.

By far the biggest attention-getter was NHK's 20-foot HDTV screen. "I'd love to own it," taxi driver Feng Zhao Heng said, "but I don't have a room that large." Yao Yunzheng, wife of a Beijing University lecturer, marveled at the fine detail in the picture. "You could see individual strands of hair and the model's complexion," she re ported.

Immediately behind the jammed NHK exhibit were booths for Panasonic and JVC, demonstrating Super VHS also to thick crowds. A JVC spokes man explained that while none of his company's Super-VHS products are available to Chinese consumers, the company exhibited in order to demonstrate the components' abilities to professional and semiprofessional users "and perhaps to encourage some shops to import Super-VHS camcorders and VCRs directly, when they see the reception these products are get ting here." Not to be outdone, Sony showed Betacam SP, 8 mm, and U Matic. The latter is widely available in Chinese department stores and specialty shops.

Packing them in among the audio exhibitors was Sansui, which featured the 130-watt/channel Vintage Series AU-X901 power amplifier with matching preamp. Bose's Acoustic Wave Cannon and Acoustimass professional speakers and JBL's pro speaker systems were prominent, along with Revox's 8285 90-watt receiver, B252 preamp, 8242 200-watt power amp, and $1,800 B226-S CD player. Chinese-made products included rack-stereo systems from Panda, a dual-well cassette deck and 25-watt AM/FM receiver from Feida, and speakers from the Shanghai Broadcast Equipment Factory.

above:

China hopes to export its consumer electronics equipment. This rack

system was part of a trade exhibit in flew York City a few months ago.

What can the determined audiophile buy? In theory, almost anything I saw at the Show. In practice, the neighborhood store probably won't have most of it, but it will have such items as a two-way acoustic-suspension mini speaker from Feida, with a 5-inch woofer/midrange driver and a 1 1/2-inch dome tweeter in a natural teak enclosure. The speaker costs $19.30 (71.50 yuan at the official exchange rate), and its sound is not bad. Or, for about $100 (370 yuan), the same company sup plies a waist-high bass-reflex model with 12-inch woofer, 8-inch midrange, and two 1 1/2-inch dome tweeters. To go with it, how about a JSGF 250-watt power amp in black, with a profile which would remind McIntosh owners of the vintage models of 20 years ago? It costs $580 (2,150 yuan). A companion Fidek preamp at $230 (850 yuan) provides inputs for tape, phono, tuner, and auxiliary; outputs for two pairs of loudspeakers, and full stereo and switching controls. To complete the ensemble, you could choose a Peony or Panda dual-well cassette deck for about $120 (450 yuan) or a more ex pensive, more professional single-well recorder from Mr. Yang's Shanghai Tape Recording Equipment Factory.

These and other audio components--microphones, keyboard synthesizers, mixers, stereo headphones, equalizers, tuners, etc--are readily available not only in the specialty shops but also in the larger department stores in cities like Beijing, Nanjing, and Shanghai.

Asked why such products are on sale in department stores at prices which seem too high for the average consumer, the manager of the audio department in the cavernous Shanghai No. 1 Department Store says that his customers include institutions, professionals, musicians, and theaters as well as audiophiles who, he admits, are a small percentage of the total. How ever, the audio department has noticed an increase in demand for professional-quality components during the past year, and its manager attributes this to China's fast-improving standard of living.

While the Shanghai No. 1 Department Store stocks an ample supply of music recorded on cassettes, there are no black vinyl discs to be seen, and the audio department seems equally devoid of turntables and phono pickups. "There's no demand for them," says the manager, a view Du Shaolin seconds. His shop sells packaged systems which contain inexpensive turntables, but there are no component-quality turntables or pickups.

"The audio cassette is the medium of choice today," he argues. "There is no demand for turntables." Although apparently there is demand, at least in the Guangzhou area, it's being met by personal imports from Hong Kong of moderately priced Sony, Kenwood, Sansui, and Pioneer models. It is with one of these that Yao replaced the aging broadcast turntable which formed part of his original stereo system. His moving-coil pickup, likewise, is a product made in Japan.

By Western standards, Yao's library of several dozen long-playing albums, mostly of Chinese popular and folk mu sic, is small indeed. By Chinese standards, it's enormous. "Very few people have the need for a turntable. Young people have cassettes. Older people, who grew up during the Cultural Revolution, don't have much interest in having music reproduced electronically in the home," he believes. For those who can afford turntables, some occasion ally "fall off the back of a truck"--an expression my translator had trouble understanding and explaining, al though it turns out that the phenomenon occurs in China, too. Some can be bought second-hand from radio stations or from public halls where they form part of the P/A system.

Casual observers of the audio scene in China who are old enough to re member audio's early days in the U.S. will notice many similarities-in the kinds of products that are available, the appearance of many of the shops, and the enthusiasm among active hobbyists. But there are differences, too such as in buying power, which, at least for the moment, outstrips the goods to spend it on. Another difference from the America of 30 years ago is a well-educated, prosperous yuppie class which wants the very best and has a pretty good idea of how to get it.

But the most significant difference may be an electronics industry determined to do, in 10 years or less, what it took the West a third of a century to do. It's an exciting, vibrant scene--one we'll all be hearing a lot more about.

(Source: Audio magazine, Apr. 1989)

Also see:

Have DAT ... will Travel (Sept. 1991)

= = = =