About the cover: this shows a laser display on the dome of the Pepsi-Cola pavilion at Expo-70. A krypton laser beam is split into four colors and then modulated by sound impulses using special mirror galvanometers. The sound system itself uses 37 speakers ranged on a rhombic grid in the dome and sounds are switched vertically and laterally at differing speeds. Eight audio sources are employed with switching matrixes. The audio-visual systems were designed by Gordon Mumma and David Tudor, who are composers, in conjunction with Bell Labs and E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology, New York). Believe it or not, the display shown was made by whales, yes, whales who are apparently to be seen somewhere in the pavilion! Probably swimming in Pepsi-Cola ...

Power Line Considerations

Q. I am a foreign student. I am about to buy an FM stereo receiver. Because the household power in my country is 220 volts, 50 Hz, I would like to know if the use of a step-down transformer will in any way affect the performance of the receiver.

Is it O.K. to use the same step-down transformer to power the receiver and the turntable? Going a bit further, is it O.K. to use the same transformer to power my audio equipment and my household appliances? In other words, is it O.K. to use one big transformer for all my needs or is it better to use several smaller ones?

-E. de Weerth, Albany, Cal.

A. There is no reason why you cannot use a step-down transformer to obtain the voltage and current required to operate your equipment. Further, all devices you plan to use can operate from this same transformer. However, when doing this, the physical size of the transformer becomes quite large. Remember that the transformer must be capable of handling the total power used by all the devices which you plan to drive with this unit. For instance, household appliances, such as refrigerators and irons, consume quite a bit of power.

You must remember one more item. The receiver is designed for 117-volt operation, but at a frequency of 60 Hz. It will operate at 50 Hz, but the power transformer will become warmer than when operated at 60 Hz. Therefore, you need to be certain that the power transformer can withstand this added heat.

Phonograph and tape recorder motors are something else again. Their speed is not determined by the voltage applied to them, but is determined by the frequency of the power source. Hence, a motor designed for 60-Hz operation will run slower when supplied with 50-Hz energy than it will when it is operated at its design frequency of 60 Hz. Therefore, you will need either a new motor or you will need some kind of pulley adaptors which will result in correct operation of the equipment. Many tape recorders and phonographs are so arranged that they can accommodate such pulleys. Hence, you see that there is no problem about the use of the step-down transformer. Whether you use one large one or several smaller transformers will be a matter of what you can obtain rather than other considerations. Remember that motors which must operate at precise speeds will have to be modified in order to compensate for the frequency difference between 60 and 50 Hz.

Electrostatic Speakers

Q. I am considering the purchase of a full-range electrostatic speaker. I am most anxious to have the following questions answered.

1. Do electrostatic speakers "wear out?"

2. Does weather affect the operation of these speakers or cause deterioration of them?

3. Do the high-voltage transformers used with these speakers fail?

4. Do these speakers require any type of maintenance?

5. Any other information regarding electrostatic speakers.

-Don R. Parman, La Canada, Cal.

A.

1. Any speaker can fail after a period of operation. Electrostatic speakers are quite delicate. If they are fed with too much power, there is danger that the diaphragm will come into contact with the outside screens. This will result in an arc which will ruin the diaphragm. Also, if the diaphragm material was not pre stretched, it could gradually sag and be attracted toward the screens and thus be ruined by arcing. However, I have heard from people who own these speakers that they just continue to operate very well over the years.

2. I have heard of a few instances where high humidity has caused some arcing and unexplained sounds emanating from the speakers. However, this does not appear to be a common problem.

3. I have never heard of these speakers failing because of high-voltage-transformer breakdown.

4. There is nothing that the owner of an electrostatic speaker can do in the way of preventive maintenance. It is unlikely that you can make the necessary repairs in the event of a failure any more than you can make such repairs with a conventional speaker.

5. The one drawback which I have noticed about electrostatic speakers is that they cannot handle large sound levels. You might have to add an additional speaker to each channel to get the kind of volume that you want. If you are not interested in really loud sound, you have no problem at all. If the sound was loud enough for you, when you heard the electrostatic speakers for the first time, you should be able to buy them with assurance that you will enjoy them.

I would imagine that if you heard these speakers in the typical dealer's showroom, that this room is larger than your living room. Thus, if the sound was sufficiently loud for you under these conditions, you should be happy with them in your smaller living room.

Stereo Cassette Player Problem

Q. I installed a stereo cassette player in my car which requires 3.2-ohm speakers. My problem arises, I think, from the two 8-ohm speakers that I mounted in the car doors. I was getting some distortion with this arrangement. High-pitched instruments sound unclear. An alto sax, for instance, sounded as if it needed to "clear its throat." Incidentally, the same tapes played on a home cassette unit sound fine.

I tried to compensate for this mismatch by adding a set of 8-ohm, four-inch speakers in parallel with the original set. These were mounted in the kick-panels. I believe this has eliminated the distortion. Now the sound is so shrill that with some recordings it is almost unbearable, even with the treble completely attenuated by the tone control.

Should an upward mismatch of 3.2 to 8 ohms produce distortion? What would you suggest as a remedy other than the obvious substitution of a pair of 3.2-ohm speakers for the original 8-ohm units?

-David H. Sexton, M.D., Knoxville, Tennessee

A. Possibly you are now getting the shrill sound because the two additional speakers are more efficient than the original 8-ohm speakers you were using. Because these speakers are smaller, they will reproduce treble frequencies more efficiently than the original speakers. This would result in the shrillness. I am guessing, of course, that the original speakers are physically larger than those you added more recently. Otherwise it just might be that the added speakers are just "brighter" and more efficient all around than the original ones.

With the 8-ohm speakers running by themselves, it is likely that the amplifier simply cannot supply sufficient power to fill the car without producing distortion.

Naturally, the mismatch of impedances results in somewhat less power being transferred to the speakers than would otherwise be the case. Further, if these speakers are relatively inefficient, this would add to your troubles. The obvious cure for the problem is to use speakers having the proper impedance, obtaining units which are as efficient as you can find. The only other solution is to use larger, more efficient 8-ohm speakers than you added. This will give you more overall sound in the car and might in the end provide better sound than could have been produced merely by changing your original speakers to 3.2-ohm units. I realize that adding larger speakers is not always easy because of the limitations imposed on you by the physical layout of the automobile.

If it should happen that one set of speakers is more efficient than the other, as is apparently the fact now, you should consider using a T-pad at the more efficient speakers so as to equalize the volume between the speaker sets. Ideally you should use the same kind of speakers that you now are using as the original. At least this will eliminate all problems arising from differing efficiencies.

==========

Dear Editor....

DEAR SIR:

I would like to thank Paul Klipsch for his article, "Another Look at Damping Factors," in your March issue. He explains that all the resistance in the circuit, even the d.c. resistance of the connecting wires, must be added to the internal impedance of the amplifier to get a meaningful figure for the true damping of the system.

Unfortunately, many people have not understood this limitation on damping.

Some have felt that amplifier internal impedance per se was a figure of merit, as if an internal impedance of 0.01 ohms were better than one of 0.1 ohms. As Mr. Klipsch points out, the amplifier is so small a portion of the circuit resistance that it can have practically no effect on damping-assuming normal design which has a generally low internal impedance.

Another source of confusion to many users is the need for matching the speaker impedance to the amplifier impedance.

Mr. Klipsch correctly indicates that nominal mismatches ( such as 16-ohm speaker and 4-ohm amplifier) make only a minute difference in response and distortion. The only effect of mismatch is that the amplifier cannot deliver its maximum power into a mismatched load. At any power less than maximum, a mismatch is of no consequence. Further, no loudspeaker maintains exactly the same impedance at all frequencies, so that even with an attempt at matching, this is a compromise which results in mismatch at some parts of the sound spectrum.

It is safe to assume that with any modem amplifier and any loudspeaker in the 4to 16-ohm range, the only matching problem to be considered is whether the amplifier has adequate power for the efficiency of the speaker used and for the size of the area to be covered.

DAVID HAFLER, President, Dynaco Inc.

==========

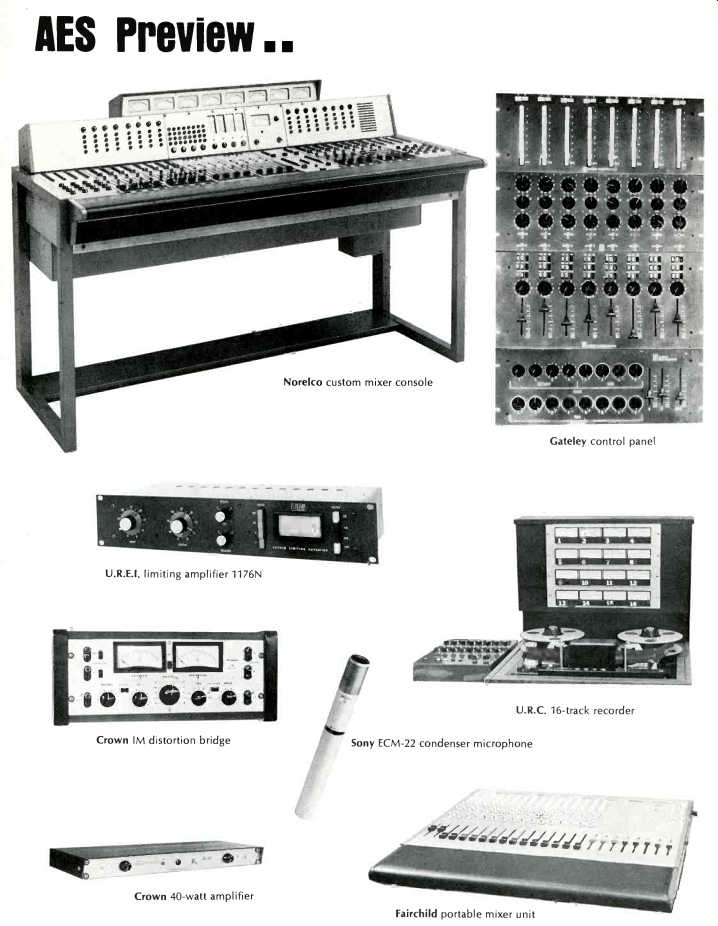

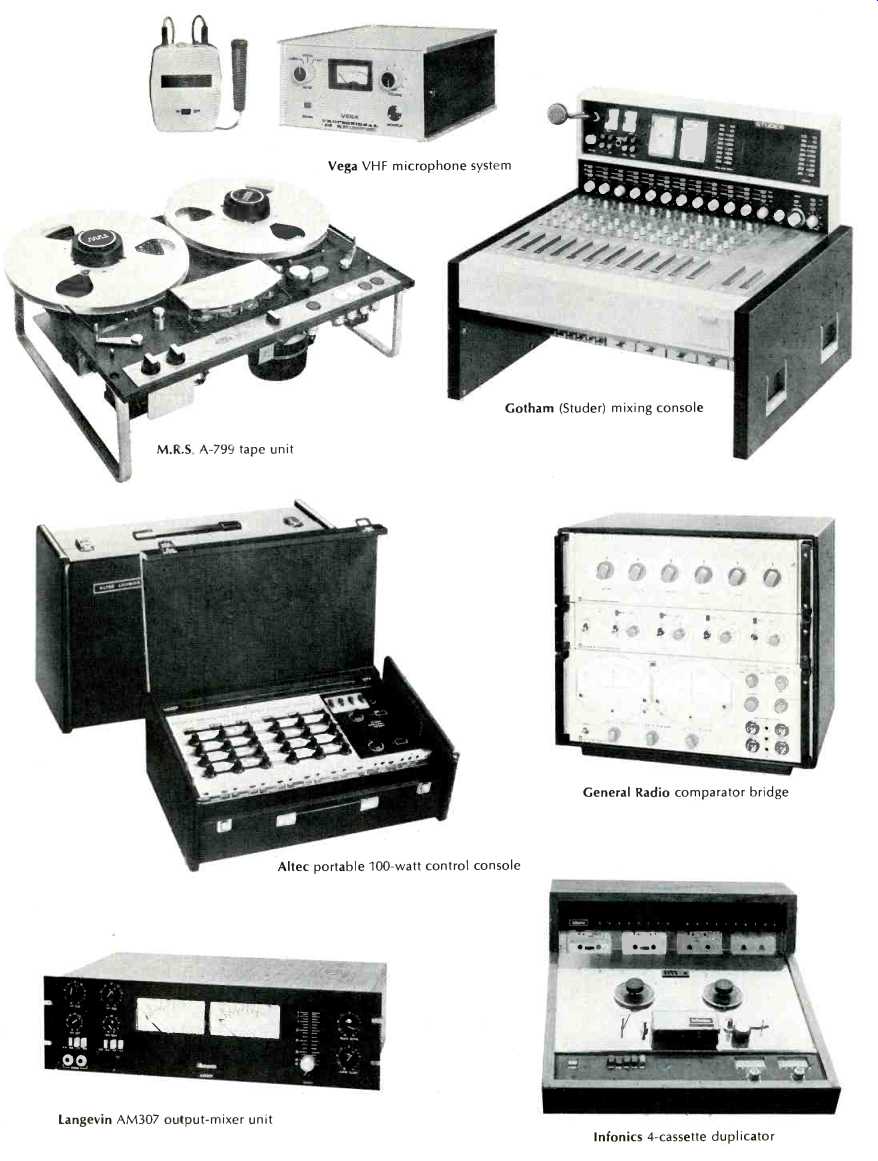

AES Preview ...

U.R.E.I. limiting amplifier 1176N, Crown IM distortion bridge, Crown 40-watt amplifier, Norelco custom mixer console, Gateley control panel, U.R.C. 16-track recorder, Sony ECM-22 condenser microphone, Fairchild portable mixer unit, Vega VHF microphone system, Gotham (Studer) mixing console, M.R.S A-799 tape unit, Altec portable 100-watt control console, Langevin AM307 output-mixer unit, General Radio comparator bridge, Infonics 4-cassette duplicator

==========

A new Electronic Synthesizer

by Alfred Mayer [Ionic Industries, Morristown, N. J. ]

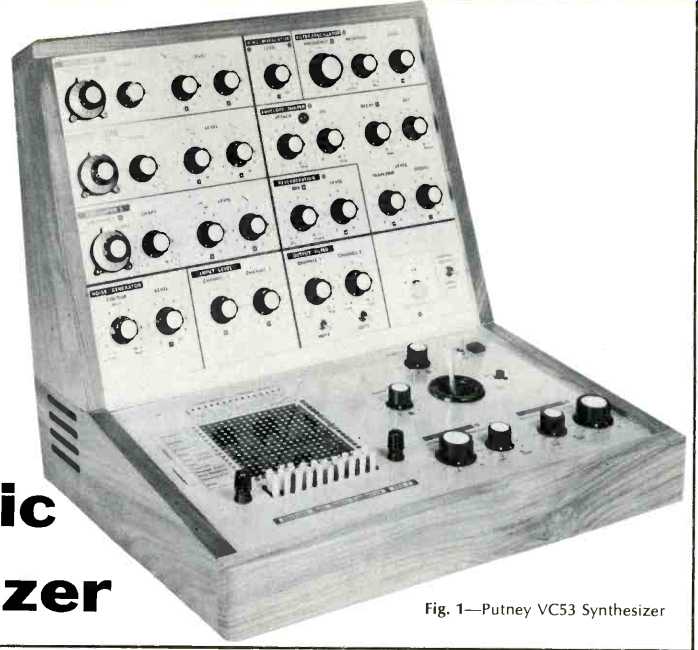

Fig. 1--Putney VC53 Synthesizer.S

SOME TWO YEARS AGO, Leonard Bernstein predicted electronic music would replace the symphony orchestra as we know it. This, with all due respect, is an extreme view and most musicians would be inclined to agree with a prominent composer who said electronics would end up as "a new voice in the orchestra." However, whether you subscribe to one view or the other there is no doubt about one thing-electronic music is definitely here to stay. The tape recorder was of course responsible for its conception; when the tape was rewound all sorts of bloops and bleeps were heard and the queer noise started people thinking. Here was a new sound that did not exist till then and with this as a start and a recorder to keep track ( sorry!) of the sound, composers experimented with natural sounds pieced together. This was called musique concrete and it was pioneered by composers such as Pierre Schaeffer in Paris. While experimenting with electronic simulated speech, the RCA Mk. II synthesizer was developed as a kind of off-shot of the program. This unit-reputed to cost anywhere from half a-million to a million and a half dollars is ensconced in Columbia university. It is the only one in existence and is now wearing out for lack of spare parts and will eventually be a 'ghost ship'. Offshoots of this initial venture ( which was pioneered by Milton Babbit) are the Moog synthesizer and Buchla systems. Some time ago, Harold Schonberg said if the price of a synthesizer could be brought down to the $3,000 to $10,000 range, every high school and college would have one in three years. Further evidence of the impact in the field was the astonishing popularity of "Switched on Bach" which presented a known and familiar work in the new medium. Today's young people are very enthusiastic about electronic music although many in their enthusiasm to break new ground want to go further and reject the past completely. I feel we must build on the past and not just dismiss it as being of no account. Many authorities have expressed the opinion that in order to be a proper candidate for electronic-compositional study, one should be able to demonstrate an understanding and some proficiency of the orchestral sound and score. We just cannot push buttons and get answers. One must have a feel for the combinations of sounds and tone-colors-in other words, the human element is still necessary in the mesh of all the electronic gear and gadgetry.

I suspect many musical people are frightened at first by some of the extreme sounds that emanate from synthesizers.

Put anyone near one and the first thing he wants to do is see how fast and high or low he can make the gadget sound.

His efforts bloop, bleep all over the lot and do not exactly win friends. However, whether we accept it or not, the synthesizer is here to stay and we ought to look at it a little more carefully and judiciously.

It has been said that the synthesizer can do all the things a regular instrumentalist can do and more. To start with, the range goes beyond the limits of human hearing in both directions. Through the magic of voltage control the multitude of possibilities is almost limitless. Compare a synthesizer to say, an organ. On an organ, you press a stop and get one set sound. On the synthesizer with voltage control you can make every sound variable in just about every manner you can imagine.

You can change the pitch, the timbre, the attack, the delay; there are so many possibilities-everything can be modified, altered, and varied. Just about any and every sound can be programmed on a synthesizer; whether it be a musical sound or noise. Sirens, the wind, thunder, lightning, trains, motors, cars, horns, and multitudes of sound effects all in a little box. A sound effects man can just go out of his mind dreaming up all the new sounds he can generate on a voltage control unit. Conventional instruments can still be played through a synthesizer and modified. With ring modulators, filters, envelopes, and trapezoids, your instrument or voice can now take on new dimensions.

Here is something to think about: at maximum, an individual with 10 fingers and two feet can sound 12 tones. With electronic devices as many tones can be sounded as the listener can comprehend, they can produce any number of rhythms simultaneously, accurately and with absolute calm and ease.

The Putney VCS3 Studio as shown in the picture is unique in that it uses no patch cords but has a matrix of 256 points that provide plotting positions numerically and alphabetically like a map reference (B 12, C4 for example) . This means that perforated templates can be marked with selected locations and placed in position over the matrix board. Complete records can be maintained in manuscript books provided. The choice of controls, whether a joystick, attack buttons or optional keyboards make for utmost flexibility and the unit can also be used with a computer. Three oscillators are incorporated with a range of .05 Hz to 20 kHz and they offer a variety of waveforms including sine, ramp, saw tooth, square, and triangular. A slow-motion dial gives a wide range of timbres and a noise generator has amplitude and coloration controls so that various bandwidths of noise can be obtained at any level. A trapezoid output provides another shape or waveform normally in the low frequencies but also used in the attack and delay facility. Treatments include an envelope generator ( attack, delay) which has an `off-time' control so that the envelope can either be automatic or manually controlled by the attack button.

Other features are a spring reverberation unit, a ring modulator and a filter. This last named device has a variable ‘Q' control which can narrow the bandwidth right up to the point when oscillation occurs so that it can be used as an additional sine-wave generator, if so desired. As a filter, the cutoff rate is 12 dB 18 dB per octave in the range 5 Hz to 10 kHz. The input amplifiers each have level controls and the output amplifiers can be voltage controlled so that amplitude modulation and automatic `fades' and `crossfades' can be applied. Pan controls which cross the left channel to the right and vice versa are also on the panel. Manual control is obtained by means of the joystick as well as the attack button. The joystick can be used to control any function on the matrix, it can operate in either channel and it can be set up with one set of controls horizontally and another set vertically.

The monitor speakers are built-in and are fed by 1-watt amplifiers. Line output is 2 x 2 V into 600 ohms and there are also 10-volt (50-ohm) outputs.

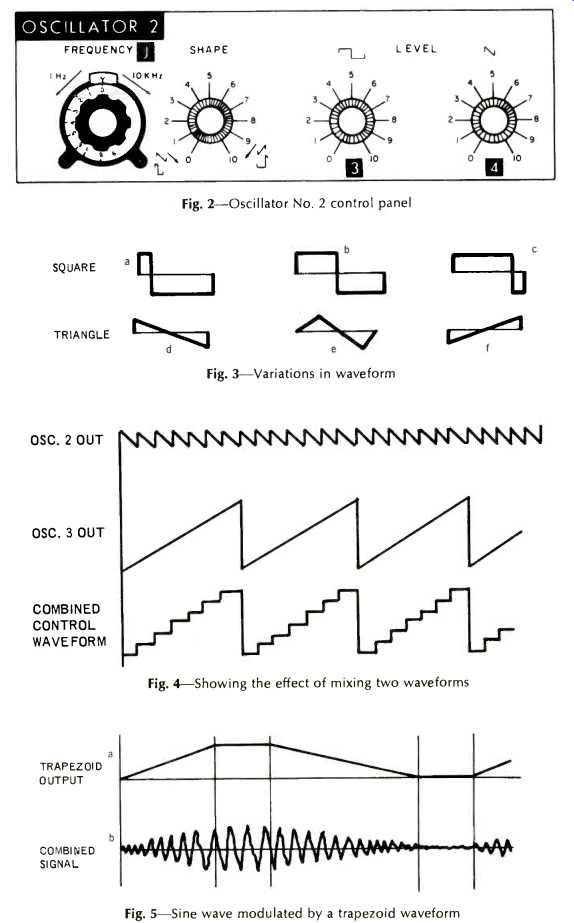

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3-Variations in waveform

Fig. 4-Showing the effect of mixing two waveforms

Fig. 5-Sine wave modulated by trapezoid waveform

Figure 2 shows the No. 2 oscillator panel, the controls being frequency, shape, and two level controls for square and ramp waveforms. The shape control enables the waveform to be varied from asymmetrical ( short pulse and sawtooth, Fig. 3a) through symmetrical, Fig. 3b, to a mirror image of the first position, Fig. 3c.

The range of this oscillator is from one cycle to 10 kHz. Figure 4 shows the effect of mixing two waveforms, the ramp of No. 2 oscillator is combined with a higher level ramp from oscillator No. 3 to form a `staircase' waveform. If this is applied to oscillator No. 1 this waveform will cause it to perform upwards or downward scales and arpeggios. Two-part chords and many other configurations can be produced by varying the controls accordingly.

Space does not permit showing all the waveforms available but one we should not miss out is the trapezoid. Figure 5a shows the waveform and 5b shows what happens when this is combined with a single sine wave. Musically, this gliding tone is called a `glissando' and it can be used with more complex configurations.

=====

Also see:

=====

(Audio magazine, May 1970)

= = = =