B. V. Pisha

Quite a number of record cleaners have appeared on the domestic market place since our last review of record cleaners in Audio, March, 1975. It is interesting to note that many of the record cleaners come from England where they either have a major dust problem or are more concerned with maintaining their records in a pristine condition. We are inclined to think the latter, inasmuch as records are quite expensive in England.

With the sensitivity of the present-day cartridges and their high compliance, any dust present in the grooves produces a sound not unlike a well-known-breakfast cereal plus a background hiss. If the record surface is not cleaned before playing, the dust has a tendency to accumulate and is eventually ground into the plastic groove by the stylus with its concomitant pressure and heat, never to be removed again.

For example, an elliptical stylus tracking at 1.1 grams generates about 16 tons of pressure per square inch on the groove wall, and stylus movement at such a pressure creates a good deal of heat. Reportedly, an elliptical stylus tracking at 1.3 grams generates about 42°C (107.6°F) in the groove. It has been reported that the lubricants used in record manufacturing frequently become annealed at these high groove wall pressures and temperatures.

Dust on records is generally not related to the cleanliness of a home. All air is dust laden, which may be readily seen in a shaft of sunlight, and all such dust collects on solid surfaces. Inasmuch as modern records are made from vinyl plastic, they can easily become electrostatically charged and attract dust from the air as well as nearby surfaces. This is particularly true in dry weather when the humidity is below about 50 per cent. Smoke, whether from cooking or tobacco, has a tendency to act like gum, causing the dirt particles to adhere tenaciously to the record. Another source of such gumminess is the breath, occurring when blowing dust from a record surface. Although the gross particles may be blown off, the near-invisible breath moisture gums up the record surface, causing the micro-dust deposits to really stick to the record. Another unrealized but very common source of dust is the actual record jacket meant to protect the record. We have examined record jackets for dust immediately upon opening them and found the jacket and record surface to be full of dust. The original source is unknown, but this dust is probably in the ambient air at the time the records are placed in the jacket. Microscopic examination of the record grooves also revealed dust present in the grooves. We believe that this dust was attracted to the record surface at the time the record was removed from the press and before being placed in the jacket. Of course, the jackets may come to the pressing plant already dust laden from the manufacturing process. We suggest that the interior of record jackets be cleaned with a slightly damp cloth the first time they're opened, particularly those made of plastic or plastic-lined.

Currently, the problem of micro-particles in the record groove has become more serious with the introduction of quadraphonic records with their four channels. Dust and dirt can cause drop-outs and distortion on these records, primarily in the rear channels where the 30-kHz carrier is used for the discrete CD-4 rear channels.

We would again like to state that, with modern cartridges tracking between one and two grams, we are unequivocally against the use of any type of chemically impregnated cloth or chemical sprays with their inherent ability to trap dirt on the record surface as well as in the grooves, thus forcing the stylus to push micro-chunks of concrete-like particles against the groove walls with attendant damage to both the walls and stylus tip. (The sole present exception to this is Ball Bros.' Sound Guard, reported on last month.)

Static

Although dust and dirt can destroy both record groove and stylus, static destroys the listening pleasure derived from playing records. Since the advent of the vinyl record, static has been a major problem, although much attention and research has been directed towards its elimination. The stylus reacts to a static charge not unlike your hand does when touching a door knob after walking across a rug-a spark is discharged, jarring the stylus, which is followed by a loud series of pops and crackles from the speakers, all most disconcerting when listening to music from records. Furthermore, the static charge attracts dust and dirt onto the record as nothing else does. Sometimes just removing a record from a plastic jacket will charge the record. The usual antistatic cleaners leave a chemical film on the record that automatically causes dust and dirt to be attracted, making it more difficult to clean. Until recently, there has been no truly effective means of removing static from the record, regardless of the numerous claims made. With the introduction of the Zerostat, the English have come through with a winner-an anti-static device that truly works, albeit temporarily. The device looks like a plastic toy pistol with a large metal trigger. In use, the Zerostat is aimed at the center of a record from a height of about 12 inches, the trigger is pulled slowly and released just as slowly and, presto, the static charge is dissipated. In normal use, we found it necessary to apply the treatment twice to ensure the removal of any measurable trace of static.

The Zerostat is not a radioactive device. Its activity is developed by a very efficient piezoelectric element which generates a high voltage, on the order of 15 to 20 thousand volts, when the trigger is slowly squeezed, thus twisting the element. Upon slowly releasing the trigger, the piezoelectric element is returned to its resting state. The generated voltage is discharged from the corona discharge needle in the center of the barrel, causing the air around the needle to become ionized in a wide arc that covers the entire record surface. On squeezing the trigger, positive ions emanate from the needle and on release, negative ions. The end result is a wholly neutralized record surface, truly free of static charge, the action taking no more than about 20 seconds to accomplish. The Zerostat treatment affects only the side of the record to be played. In our experience, we find it most advantageous to have the Zerostat next to the turntable and to apply it immediately after we clean a record. It is amazing how noise-free most records are when they're static and dust free.

We might add that the Zerostat treatment is also useful in eliminating static from the plastic turntable covers, in the photographic laboratory where it is essential to keep dust from the negatives and prints, and in the assembly of any optical elements in the make-up of lenses.

A word of caution is in order. The Zerostat is not a toy and.

should never be pointed and discharged at any human or animal, particularly in the region of the eyes, even though it is claimed to be safer than the static charges generated by walking across a rug. Above all, keep it away from children.

The Zerostat is available for about $30.00. Considering the fact that its life expectancy is about ten years, it is not that expensive for the results that are obtained when properly used.

Liquid Cleaners

As in our previous study of record cleaners, we left a good number of records exposed to the air in our laboratory as well as in the garage. Artificially dirty records were also produced with cigarette ashes and vacuum cleaner dust. Because of the nature of some of the record cleaners to be tested, we obtained about 100 records from the "peanut butter-and-jelly" set. Aside from the numerous scratches present, the records were smeared with an untold number of finger prints plus whatever else had adhered to the fingers during the course of any given day. It is doubtful that any audiophile would have records this dirty. However, these records proved to be most useful in determining the ability of the various record cleaners to truly clean a record.

During the tests, all records were examined with a wide field stereoscopic microscope just prior to being cleaned and immediately after. Before cleaning the record, it was treated with the Zerostat so as to facilitate the cleaning process. All records were tested for static charge immediately after cleaning and 15 minutes later. Most of the records cleaned with a liquid cleaner had only a small static charge left on them.

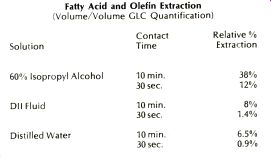

Record cleaning fluids are generally mild detergents such as Alconox or a formulation containing varying strengths of alcohol. From our experience, we question the use of these types of cleaners, particularly since it has been established that contact with alcohol, Alconox, and certain anionic detergents does, in effect, oxidize the surface of the vinyl disc after a period of time. Alcohol, in almost any strength, has been identified as one of the cleaning fluids that leech out from the vinyl surface the important stabilizers and lubricants necessary for the longevity of records. Stabilizers are needed to counteract the high-heat conditions created by the stylus and for subsequent vinyl integrity, while lubricants assist in good stylus/surface contact and slippage. Unfortunately, these important chemicals are extractable from the record surface by almost any solution, but in varying degrees. By way of comparison, on a 0-100 continuum, extractions of fatty acid chains and the polyolefin groups from vinyl records by three solutions are shown in the accompanying table.

Fatty Acid and Olefin Extraction; Volume/Volume GLC Quantification)

Solution

above table: 60% Isopropyl Alcohol DII Fluid Distilled Water Contact Time Relative Extraction 10 min. 38% 30 sec. 12% 10 min. 8% 30 sec. 1.4% 10 min. 6.5% 30 sec: 0.9%.

Fortunately, the integrity of the vinyl compound is not damaged to the point of making a record unplayable until the cleaning solutions have been applied to the record surface over long periods of time. The process is insidious and eventually will cause damage. It appears that any liquid put on the surface of a vinyl record will exhibit some extraction characteristics, be it distilled water, alcohol, detergent, or the Discwasher DII solution; there just isn't a perfect record cleaner.

There is a great deal of data available on liquid record cleaners and their action on vinyl records and additional data is forthcoming from continued research in this field. At the moment, we seem to have raised more questions than answers. However, it is our intent to publish the results of these experimental findings in the near future.

A word of caution to collectors of acoustic and early electric shellac records is in order. Shellac is quite soluble in alcohol. Any strength of alcohol in a record cleaning solution will cause some damage to the shellac record surface, and it can also totally destroy the record.

Brushes

There are numerous brushes available for removing dust from the record surface. Unfortunately, the brushes generally remove only a small portion of the dust that collects on a record exposed to room air for a 24-hour period. Microscopic examination of record surfaces after cleaning with a brush show that although some brushes do reach the bottom of the groove, they simply push most of the dust into a pile at the point where the brush was removed, leaving a line across the record that is not generally visible with the naked eye. Some brushes, when held at a slight angle, do remove a good deal of the dust, and those that are wetted ever so slightly with a cleaning agent and held at an angle do a much better job of removing dust. Only two of the available brushes, when used as directed, were capable of cleaning truly dirty records to a really satisfactory level of cleanliness.

No brush currently available has been able to remove more than about 90-95 percent of dirt found on the records we borrowed from the "peanut butter-and-jelly" set.

In spite of our experimental findings, we are of the opinion that some form of brush "dusting" of records should be employed by everyone. It is far better to remove some of the dust from a record each time it is played than to permit the dust to build-up to the point where the record simply becomes unplayable due to the noise generated by collected dust.

Record Cleaning Devices

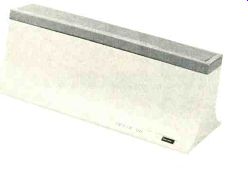

The monarch of record cleaners, without a doubt, is the Keith Monks Record Cleaning Machine, Mark 2, imported from England, and retailing for the princely sum of $1350.00. There is also a dual device (Mark 3) available for $1835.70. As the photographs show, the Keith Monks unit is larger than a normal turntable, weighing 68 pounds. The unit uses a 50 per cent alcohol (methanol) solution to clean the records, which, subsequently, is removed along with any debris on the record surface by the suction arm as it "plays" across the record. The vacuum is developed by a 1/12th hp motor-vacuum pump combination.

The Keith Monks Record Cleaning Machine would rarely be used more than once a year to clean a record, since it is not meant to be used simply for the removal of surface dust.

The effects of using the 50 percent methanol solution would, accordingly, not be noticeable until a few years had passed. This device is most useful when terribly dirty vinyl records are to be cleaned, like those we borrowed from the "peanut butter-and-jelly" set. Without a doubt, it is the most efficient record cleaner available, as microscopic examination of the cleaned records showed that all the debris and fingerprints had been removed. Some static developed on the record surface as the vacuum arm traversed the record, but this was easily remedied by applying the Zerostat anti-static treatment.

Despite the efficiency of the alcohol cleaning solution in removing all the "dirt" from the record grooves, we cannot recommend the Monks machine for routine use because of the solution's potential destructiveness. In view of our misgivings, we examined a few other record cleaning solutions in order to find an efficient substitute for the alcohol solution. Experimental findings indicated that the most efficient solution to use with this device is the Discwasher DII cleaning solution, diluted one part of DII plus three parts of distilled water, stabilized at a pH of 6.81/4the same pH as the DII solution. This dilute solution produced results similar to or better than those obtained with the 50 per cent alcohol, but at a lesser risk of extracting essential record components.

The D-II solution also extracts stabilizers and lubricants from the records, but only slightly more than distilled water, which is very little. A DII solution this dilute would be relatively ineffective with the Discwasher pad.

After using the Keith Monks machine for awhile, with the dilute DII solution, we were convinced that it is the only way to convert really "dirty" records to a pristine condition. Because of the cleaning results obtained, the Keith Monks Record Cleaning Machine, Mark 2, became one of our two reference standards for this study.

Another excellent record cleaning device is the Fidelicare Spin and Clean Record Washer, selling for $19.95. The Fidelicare washer consists of a plastic tank filled with the cleaning solution, with roller guides to restrict the record insertion depth so as to keep the label dry. The record is placed between two cleaning pads and rotated by hand first in one direction and then in the reverse direction. Subsequently, the record is removed and dried with a lint-free cloth supplied with the unit.

The cleaning solution used with this device is a dilute solution of Alconox. Checking a dilute solution of DII against the dilute Alconox solution, we found the DII to be the better cleaning agent.

Although we found this unit to be one of the most efficient record cleaners for dirty records, we had some small misgivings about the cleaning pads. When the cleaning solution was left in the tank overnight, the pads became soft and lost their ability to reach to the bottom of the grooves.

We believe that the efficiency could be substantially improved if the pads were replaced with proper size brushes, and present users should store the unit only when empty.

The efficiency of this record cleaning device, used with the dilute DII solution, compared rather favorably with our two reference standards. Collectors of shellac records should find it most useful.

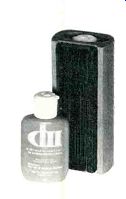

The Discwasher, retailing for $15.00, is now available in a slightly improved version, with the backing made with a long-fiber, highly absorbent cotton, while the slanted cleaning fibers are made of very fine nylon. The DII solution is applied to the edge as before, but when the brush is rotated towards the opposite edge, the very fine nylon fibers act in a capillary manner whereby the liquid on the record rides up the nylon fibers along with the debris, to be absorbed onto the backing material. Eventually, the backing takes on a brownish-white color, indicating that it is full of dust particles and should be cleaned and vacuumed per the enclosed instructions if the dust particles are not to be re-deposited on subsequent records.

We found the new version of the Discwasher to be more efficient in cleaning truly dirty records than the previous model. This is probably due to the specific slant of the nylon fibers and the improved capillary action of the pile. Daily use of the Discwasher did maintain records in a dust-free condition. Any static generated was easily removed with the Zerostat. The Discwasher was our other reference standard for this review of record cleaners.

The Lencoclean "1" record cleaner is unique in that the stylus continuously travels in a wet record groove. The device, selling for $13.25, looks like a tonearm, with the small brush at one end of a tube containing the dilute alcohol solution and a counterweight and fluid reservoir at the other end. The arm rests on a pin located on the turntable. When the brush is placed on the record, the cleaning solution comes out of the brush base, over the bristles, and onto the record. In principle, a track of dilute alcohol is placed on the record just ahead of the stylus, causing the stylus to ride a wet groove. The bristles of the brush appeared too large to effectively reach to the bottom of the groove, and their purpose seems to be mainly a means of dispensing the cleaning solution on the record and to pickup any larger particles on the record. Microscopic examination of the record grooves

after using the Lencoclean "L" brush and solution showed that little or no debris was removed from the very bottom of the groove, though particulate matter on the surface was picked up. The alcohol solution did not evaporate quite as readily as claimed, and the test records had to be thoroughly dried with a lint-free cloth or tissue paper before being returned to their jackets for storage. Dust on the record surface was either removed by the brush or pushed towards the center of the record where it can be removed when the record is dried.

Although we did not investigate the claim that the stylus tip has less wear when playing a wet record, the report published in the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, Vol. 22, No. 10, p. 800, December, 1974 discusses this claim and presents some interesting photomicrographs showing the wear on a stylus tip by the normal dry technique and by the wet technique.

The Vac-O-Rec cleaning device, $29.95, has been somewhat improved during the past year. It now comes with a small brush, similar to those used with electric razors, for cleaning the mohair pads, and more detailed instructions on the best way to use the unit accompany it. There is a plastic wrap on the brush handle, which is inserted into the record cleaning slot, so that the unit will accept 45-rpm records for cleaning. Thus, the Vac-O-Rec can now be used for cleaning of all standard size records.

The new Vac-O-Rec performed better than the original unit, though some dust particles still remained in the bottom of the record grooves. When the mohair pads are cleaned regularly with the supplied brush and vacuumed from time to time, the dust streak left by the pads of the original unit when the record was removed is no longer visible to the naked eye. A fan in the unit acts as an exhaust, drawing in air through the record-cleaning slot and expelling it from the bottom of the unit. Records with large amounts of static have their charges reduced to almost nonexistent levels while in the unit. Though some static is built up when the disc is removed from the unit because of friction by the mohair brushes, this is at a low charge level and is easily removed, if bothersome, by treatment by the Zerostat. The Vac-O-Rec was judged effective in removing surface dust in day-to-day record maintenance and appeared particularly quick to use.

The Metrocare Hi-Fi Kit/3, $9.95, comes from England, and contains a 5 by 7/8 by 1-1/4-in. velvet pad, an ounce of non-alcoholic record cleaning fluid, a 7-1/2 cc bottle of alcohol-based cleaning fluid for styli, and a stylus brush with two tufts of bristles. The pad, which is called an "ioniser," is claimed to direct ions on the record in one direction, thus eliminating static, and to pick up dust and dirt. Three or four drops of the fluid are placed in each of two holes on top of the pad housing, bringing the pad to a humid dampness.

The unit was effective in diminishing the static charge on a record and removing surface dust accumulation, acting somewhat like the well-established Watts Preener. However, it does not remove particulate matter from the bottom of the groove or fingerprints.

The Memorex Record Care Kit, $5.95, contains a plush roller brush, a bottle of dilute alcohol cleaning solution, and a stylus brush, all in a plastic case that is essential to the operation of the record cleaner. On the bottom of this storage case is a foam pad that must be moistened with the cleaning fluid. The plush cleaning brush is placed on the moist foam pad and the case lid is closed tightly to allow proper humidification of the brush. In use, the humidified brush is applied to the surface of a rotating record. Like all record care units of this type, its usefulness is limited to removing dust from the record surface, which it does quite well. It does not remove fingerprints or dust from the bottom of the record grooves. Although no anti-static claim is made for the device, static present on the record surface was diminished after using the plush brush as directed.

The Decca Record Cleaner, $15.00, consists of an arm with a 5/8-in. wide brush on one end and a counterweight on the opposite end. The unit may be adjusted vertically to accommodate various turntable heights. Provision is made to ground the unit to the turntable, thus creating a pathway for the discharge of any static charge present on the record through the bristles which are conductive. The unit is used without any fluids, and its specially designed bristle tips do reach the bottom of the record groove. The unit operates on a tonearm principle just ahead of the stylus, somewhat like the Dust Bug. It does remove dust and static charge, as claimed. Microscopic examination of the record grooves after treatment with this unit revealed dust particles to be present, but to a lesser degree than with many similar types of add-on brush cleaners. Surface dust was effectively removed with this cleaning brush.

The Decca Record Brush, $15.00, is a hand-held unit which comes with an aluminum stand on which the brush is stored. To use the unit, the brush is slid on its track so that the bristles rub across two rods which remove any accumulated dust from the bristles. There are no fluids used with this brush, although the brush was quite effective in removing surface dust particles. Dust particles were not re

moved from the very bottom of the groove, but appeared to have been shifted from one spot to another. A minimal static charge was on the record after use of this brush, but was easily removed with the Zerostat.

The Keith Monks Record Sweeper, $18.95, is unique in that it does not have to be physically attached to the turntable. It consists of a heavy metal base and an arm with a brush at the end of it, the arm riding on lateral pivots. To eliminate static or static build-up, the unit is grounded. It is used in a manner similar to the Dust Bug. Microscope examination of the record grooves reveals dust particles at the bottom of the record grooves. The unit is effective in removing surface dust that is attracted to the record. Static build-up is easily dispersed with the Zerostat.

Conclusions

To conclude, it is most important that records be kept clean of surface dust before and after each play. Although alcohol is detrimental to the surface of vinyl compound records, its effects are noted only after a period of time. All of the record care devices examined in this study will keep records free of surface dust.

The outstanding cleaning device for truly soiled records is the Keith Monks Record Cleaning Machine used with the dilute DII fluid. Needless to say, only the most affluent of audiophiles can afford such a record cleaner in their home.

It would be nice if our high-quality domestic record shops would follow the English and install in their store a Keith Monks Record Cleaning Machine and clean their customers' soiled records for a nominal fee. Another good location for this cleaning device would be the libraries which loan records, such records to be cleaned before being returned to the stacks. Repositories of valuable shellac records as well as LPs, e.g., the Rodgers and Hammerstein Library and the Library of Congress, would seem likely candidates for this cleaning machine to maintain their collections in a pristine condition.

As far as cleaning deeply soiled records is concerned, the Fidelicare Spin and Clean Record Washer, when used with the DII solution, will do a commendable job.

For the daily care of records, to wit, the ounce of prevention that can assure your records of reasonable longevity and noise-free plays, the Discwasher with DII solution and the Zerostat should do the best job of keeping your records clean with a minimum of noise problem.

------------

ADVERTISEMENT:

SC-1 --

The only stylus cleaner

DISCWASHER--

The superior record cleaner

Announcing : The technology of the Discwasher Group

announces a system-a protective environment-utilizirg an improved dry friction

reduction agent and a radically new application

method.

Dry lubricants. ALL reed the Discwasher

system (see Audio, April 1976).

None car match the PRO-DISC environment.

(Soon at your Discwasher dealer)

ZEROSTAT --The static killer

GOLD-ENS--

Perfectionist cables

Discwasher Group --909 University, Columbia. MO 65201

++++++++++

--------------

(Audio magazine, 1976)

Also see:

= = = =