by LEONARD FELDMAN

Until very recently, major manufacturers of video equipment paid very little attention to the quality of audio their products delivered. Although FCC rules allow the audio portion of TV broadcasts to have as wide a frequency response range as is used in FM broadcasting, makers of TV sets have traditionally equipped their sets with low-power audio amplifier circuitry and small, improperly baffled loudspeaker systems. While there were occasional TV broadcasts with good quality sound, that quality never made it to the viewer's ears because of TV set limitations.

The audio quality available from home videocassette recorders also left much to be desired. Operated at fastest tape speed (Beta II in Beta-format machines, or SP in VHS VCRs), some of these recorders could deliver frequency response extending to a bit beyond 10 kHz, but their levels of distortion and wow and flutter were well in excess of what any serious audio enthusiast would tolerate. At slower tape speeds, commonly used to obtain longer continuous recording time, high-frequency cutoff was even worse (often not much better than 4 or 5 kHz), and other performance areas suffered further degradation.

In recent years several events have combined to draw attention to the poor quality of audio for video. Simulcasts, in which local FM stations carry the stereo audio associated with video concerts, have introduced the viewing public to the pleasure of better sound as an accompaniment to their TV programming. Many cable TV services offer stereo music (via the subscriber's FM radio) as an accompaniment to some of their video programs. There is talk of imminent standardization of stereo audio for broadcast TV programs, and general awareness that just switching to stereo will not improve sound quality. Finally, people are beginning to combine their audio and video systems and to discover, in so doing, how bad the audio quality of their TV sets and VCRs really is.

For more than a year there had been rumors about a new and better method of recording the audio tracks on video tape. Until the official announcement came in early January, none of us suspected just how good the new system would be. It turns out to be better in terms of dynamic range, wow and flutter, and distortion than even the best audio recordings made on the costliest open-reel audio tape recorders! The new system is called Beta Hi-Fi and it is being adopted by all of the Sony licensees who make and distribute Beta-format VCRs. They include such well-known names as Aiwa, Marantz, NEC, Sanyo, Sears, Teknika, Toshiba, and Zenith plus, of course, licensor Sony. Recent additions to the list of licensees are Pioneer and Nakamichi.

Beta Hi-Fi Versus VCR Low-Fi

To give you some idea of just how much of an improvement in sound quality the newly announced Beta Hi-Fi system offers, here are some comparisons between its claimed performance characteristics and those of either conventional Beta VCR sound reproduction or VHS audio quality:

Audio signal-to-noise ratio in conventional VCRs runs around 40 dB; a bit higher if you use top-grade tape and are lucky enough to get a machine that's on the good side of nominal specs. It doesn't take a "golden ear" to hear that ever-present tape hiss, which gets even worse at slower tape speeds (Beta III or, in the case of VHS, LP or EP). Even the poorest quality standard audio cassette tapes, operated in low cost cassette decks without any Dolby or other noise-reduction system, yield considerably better signal-to-noise figures than that these days. Beta Hi-Fi offers a dynamic range (or signal-to noise ratio, if you prefer) of more than 80 dB! Consider the matter of frequency response. The very best VCRs I have ever measured offer treble response out to perhaps 12.0 kHz at their -3 dB cutoff points. At slower tape speeds they typically begin rolling off response at around 5 kHz. Neither conventional Beta nor VHS VCRs ordinarily repro duce frequencies below 50 or 60 Hz.

The Beta Hi-Fi system boasts flat response from 20 Hz to 20 kHz-the full range of human hearing. Furthermore, it makes no difference whether the re cording is made at the faster Beta II or the slower Beta III tape speed.

Harmonic distortion, which typically runs around 3% for the audio signals played back on conventional VCRs, is reduced by a whole order of magnitude--all the way down to 0.3%--in the new Beta Hi-Fi system. (That's referenced to maximum recording level.) Finally, perhaps the most annoying defect in the soundtracks of conventional VCRs, wow and flutter, is reduced to insignificant levels in the Beta Hi-Fi sound system. In conventional VCRs I have measured wow and flutter figures as high as 0.5% to 0.75% wtd. rms when recordings are made at slowest tape speeds. In Beta Hi-Fi sound reproduction, wow and flutter has been reduced to less than 0.005% and is, for all practical purposes, inaudible.

High Speed on Slow Tape

With these performance specifications, you might conclude that Beta Hi Fi utilizes some sort of digital technology. In fact, at the press conference which announced the development last January, just that sort of misconception seemed to be present, judging by some of the questions that were asked. Certainly, the performance does come remarkably close to that mentioned in connection with compact digital discs and PCM processors, but Beta Hi-Fi is very much an analog and not a digital sound system. As such, it may well find its niche in the world of audio as a future competitor to digital sound, but more of that presently.

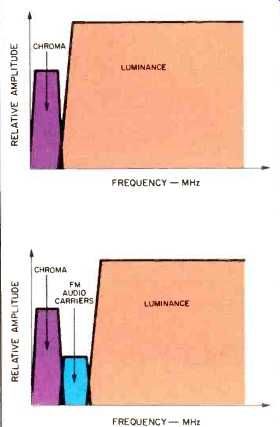

Fig. 1--Frequency spectra of a conventional video head (top), and Beta

Hi-Fi video head (bottom), show how Beta Hi-Fi sandwiches the new audio

signal between the chroma and luminance signals.

As you may have already guessed, the audio information in the Beta Hi-Fi system is "laid down" on the magnetic medium using the same fast-spinning heads that are used to record the video signals. In other words, instead of the tape writing speed for the audio signals being limited to only a couple of centimeters per second (when a stationary audio record/playback head is used), the effective tape writing speed is now the same as that used for the video signals, typically 6.9 meters per second in the case of Beta. Given the wide bandwidth that results, it be comes possible to use what amounts to an r.f. (radio frequency) carrier (see Fig. 1) or, more correctly, two separate r.f. carriers, each of which can be frequency modulated by a left- or right-channel stereo audio program. These two extra carriers are neatly nestled into the available spectrum between the chroma (color) and luminance (brightness) video signals. In the Beta VCR format, the luminance signals are located between 3.5 and 4.8 MHz, while the chroma signal is centered at 688 kHz. It is an amplitude modulated or AM signal whose upper sideband somewhat overlaps the FM luminance signal spectrum.

An interesting side benefit arises from this arrangement, besides the superb performance already outlined. If you operate the fast scan feature of a Beta VCR (say, at two or three times normal viewing speed), the audio doesn't take on the "chipmunk" quality that is characteristic of conventional audio tape reproduction at higher than normal speeds. If you stop to think about it, actual tape-head to tape writing speed doesn't really change that much when the longitudinal tape speed is increased by two or three times or, for that matter, when it is decreased for slow-motion viewing.

That's because the longitudinal tape speed is a very small part of the total effective tape-to-tape head writing speed when we talk about the video recording heads.

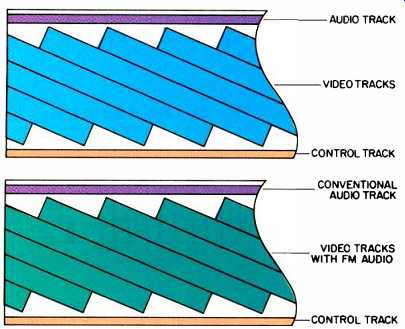

The Beta Hi-Fi track allows for total compatibility with earlier hardware and software. The conventional longitudinal audio track, read by a stationary audio tape head, is still present on a Beta Hi Fi tape, as shown in Fig. 2. An older Beta videocassette played on a new Beta Hi-Fi VCR will still deliver its old (albeit inferior) audio sound, as before.

Fig. 2--A comparison of track for mats between conventional Beta (top),

and Beta Hi-Fi video shows no difference in layouts so that there

is perfect compatibility in this regard.

And, because newer Beta Hi-Fi cassettes will have a monophonic (L + R) equivalent soundtrack recorded longitudinally where it always was (in addition to the two FM-modulated audio tracks that become part of the video composite diagonal tracks), newer tapes can be played back on conventional Beta-format machines. The avail ability of three audio channels suggests, too, that some enterprising soft ware producer may, sooner or later, come up with a movie that employs ambience enhancement using the third limited-bandwidth longitudinal channel.

Measure for Measure

I recently had an opportunity to measure the audio section of a prototype Beta Hi-Fi VCR which came through my lab. The unit, a Sony Model SL-5200, will be available later this year.

While I can't speak for the video quality of this machine, I was able to measure audio performance much as I would for a high-quality audio tape deck. Using a Sound Technology 1500A Tape System Tester and the hard-copy video printer that's connected to it, I documented some remarkable performance characteristics for this machine. All during the measurements, I had to keep reminding myself that this was not a digital PCM system.

Figure 3A represents a plot of record/play frequency response at a nominal record level of 0 dB. At 18.5 kHz, response was down a mere 1.2 dB! Meter calibration on this machine ex tends to a +6 dB notation, which is followed by a red "over-record" warning light. Since metering of this type is arbitrary and related to the amount of FM deviation of the extra carriers rather than to any tape saturation characteristics, I pushed up the level to the maxi mum allowable metered indication just short of the over-record notation. Under those circumstances, there was some roll-off at the high end (-4.1 dB at 20 kHz) and a lesser amount of roll-off (1.8 dB) at 20 Hz. (See Fig. 3B.) The excellent results obtained at this higher record level suggested that the meter calibration's 0 dB point was put there as a safety factor for inexperienced recordists and that other measurements ought to be made relative to the higher +6 dB mark on the metering system. So, to determine the distortion characteristics of the system, I re adjusted the test instrument's reference level so that its 0 dB point actually caused a recording level of +6 dB on the VCR's metering system. Even at this higher recording level, third-order distortion was an incredibly low 0.12%, as shown in Fig. 4A. Raising the level, which moves the dotted line cursor up from the nominal 0 dB point shown in Fig. 4A, I determined that 3% third-order distortion occurs at a bit under +7.0 dB relative to the new reference level (that's a full + 13 dB above the nominal 0 dB point on the VCR's own meters). The new distortion level for +7 dB is 3.4%, as shown in Fig. 4B.

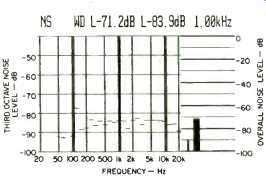

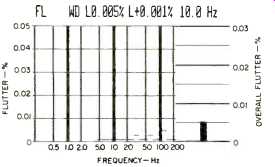

I measured signal-to-noise relative to the newly established 0 dB reference level of the test instrument and came up with an A-weighted S/N value of 71.2 dB, as shown at the top of Fig. 5. To this must be added the +7 dB of extra headroom that was previously determined (Fig. 4B), bringing the effective dynamic range of the system up to an incredible 78.2 dB! Remember, there is no form of companding or electronic noise reduction employed here. Finally, I recorded a 3-kHz test tone onto a videocassette and played it back to determine wow and flutter. As shown at the top of Fig. 6, it measured 0.005% wtd. rms, exactly as claimed!

Competition for Digital?

As a result of the introduction of Beta Hi-Fi, several questions arise concerning the emerging digital audio technology. If you can get that kind of audio performance, along with a TV picture, using purely analog techniques, is the industry perhaps placing too much emphasis on the coming digital audio era? The question arises on purely economic terms, since the addition of Beta Hi-Fi to a conventional VCR is estimated to add no more than $100 to its cost, leaving the VCR's price not much higher than the proposed price of some CD players. And certainly, the cost of such a VCR has got to be a lot less than the cost of a PCM processor plus any type of VCR, the elements now needed for recording digital audio on tape. Looked at from that point of view, the ability to record pictures as well as such high-quality stereo sound is almost an extra bonus, one that you can ignore, if you so choose, by not even using it for video.

Fig. 3--Record-replay frequency response of Beta Hi-Fi system at 0 dB

record level on meters (A) and at +6 dB meter indication (B).

Fig. 4--At 0 dB record level, third-order harmonic distortion measured

only 0.12% (A), while 3% third-order harmonic distortion occurred at

a record level of just under +7 dB on the unit's meters (B).

Fig. 5--Signal-to-noise ratio measured relative to 0 dB record level

was 71.2 dB, A-weighted. Adding +7 dB to this figure gives a dynamic

range of more than 78 dB.

Fig. 6--Wow and flutter of Beta Hi-Fi unit measured only 0.005% wtd.

rms.

(Source: Audio magazine, May 1983)

Also see:

VHS Hi-Fi: Five Units Tested (Nov. 1984)

Deck to Deck Matching and NR: Straightening the Mirror (Aug. 1986)