This article is adapted from a chapter of The New Sound of Stereo, a book by Audio's Technical Editor, Ivan Berger, and Hans Fantel, syndicated audio columnist for The New York Times. The book was published in February 1986 by Plume, a division of New American Library. C. 1986.

By Ivan Berger and Hans Fantel.

Car stereo is a mixture of the familiar and the unfamiliar. As in home stereo equipment, you can get all-in-one systems or build up systems from separate components, and manufacturers' specifications are available to give you some idea of how a system will perform. However, the mixture of components is different in car systems (for example, the tuner and tape deck are nearly always combined), some of the specs must be read with a critical (even skeptical) eye, and the car's spatial and acoustic limitations make installing a good system much trickier.

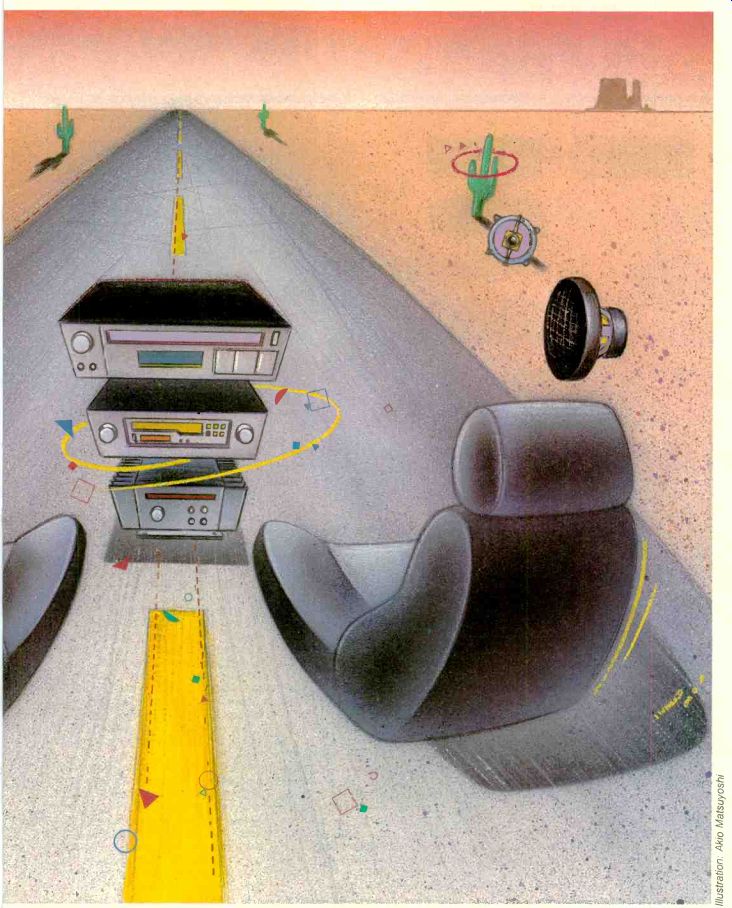

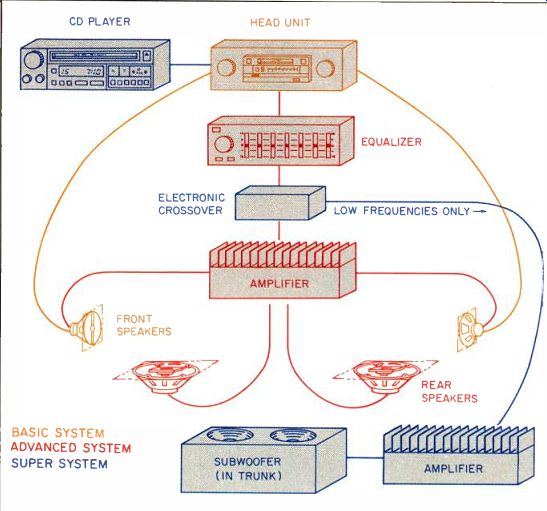

The systems made up of these components vary in complexity (Fig. 1). A typical, basic car sound system will consist of a single in-dash unit (variously called the receiver, head unit, or deck) combining a tuner, a cassette deck (for playback only; car decks rarely record), and an amplifier, plus a pair of speakers. Speakers are commonly mounted in the dashboard or front doors and in the parcel shelf, or rear deck, between the top of the back seat and the bottom of the rear window.

The amount of space available for the amplifier section of a basic system's head unit is limited, so those systems don't have much power on tap. To get more power, complex and advanced systems may include separate amplifiers (often larger than the entire head unit), and may include a frequency equalizer as well. Sometimes, the amplifier and equalizer are combined; if not, the amplifier is usually installed out of sight.

More expensive "super systems" will usually include a crossover and separate amplifier to power a subwoofer, and may even include several crossovers and amplifiers to separately power each loudspeaker driver. Increasingly often, such systems will include a Compact Disc player in addition to, or instead of, the cassette deck. In advanced and super systems, the number and placement of speakers (other than subwoofers) will be pretty much the same as in a simple system, but those speakers will usually be of higher quality.

Fig. 1--In basic car-stereo systems, the head unit (tape and tuner sections)

in the dashboard drives the speakers directly. In more advanced systems,

separate amplifiers are used, allowing higher power output; equalizers

may be separate (as shown), be combined with amplifiers, or be omitted altogether.

The most advanced super-systems add an electronic crossover to route the lowest

frequencies away from the main amplifiers and speakers, and through a separate

amplifier and subwoofer. CD players are also found in expensive systems.

The Receiver

A car-stereo receiver must be selected with an eye toward the kind of system it will be used in. Lower cost receivers (roughly $100 to $350), de signed for use in basic systems, have built-in amplifiers of fairly low power (typically less than 5 watts per channel) so they can drive the speakers of such a system directly.

Many medium-priced units (typically $200 to $600) have both amplifier and preamp outputs. While they can be used without additional amplifiers, the extra outputs allow the system to be expanded with separate high-quality amps when the money is available.

Few buyers, however, actually do expand their systems because of the difficulty of getting at components and wiring after installation. The most deluxe receivers (about $500 and up) generally have no built-in amps at all, on the assumption that they will be used only in advanced or super systems with external amplifiers.

Control-panel design is far more critical in car than in home stereo receivers. The car receiver must cram all the controls of a typical home system into a front panel smaller than that of any single home component. At the same time, those controls must be easy for the driver to find and use, both day and night, while keeping his eyes on the road. To complicate the designer's life still further, no two users (or designers, for that matter) quite agree on what controls should be emphasized and on what design makes them easiest to use. Before buying a receiver, check its controls, preferably from about the same relative position as you'll occupy when driving, to make sure its design is convenient for you not just for comfort, but for safety.

Because a car-stereo system must compress nearly all a home system's functions into such a tiny space, it may lack features you would miss. For example, many systems omit tape-equalization switching or noise reduction, which critical listeners will want. So make sure that your choice has all the features you need.

If it's simple to use, automation be comes a safety measure in the car; two common forms are scan tuning and seek tuning. Every time you press the seek control, the tuner advances to a new station, so you don't have to tune manually to find where the next station is. Scan tuning samples each station for 5 to 10 S, then moves on to the next; you stop the search when you hear something you'd like to keep listening to. On most sets, scan and seek work only in one direction, from lower to higher station frequencies; on a growing number, though, they work both ways, which is more convenient.

Diversity tuning, another automatic feature, constantly compares the signals from two antennas, selecting as its signal source whichever is better at any instant.

Even more automation is usual in the tape section. There are equivalents of station seek (often called music search or any one of many similar names) and of scan tuning (called tape scan), both usually operating bidirectionally. Auto reverse is common, and systems with out it frequently have auto repeat, which lets you repeat the same side of the tape over and over. It's even more important to have a system which disengages the transport from the tape when it's done playing or when the car's ignition is turned off. Otherwise, the rubber pinch roller that holds the tape against the transport's capstan will develop flat spots, causing wow and flutter during subsequent tape play. One such system is key-off eject, which automatically ejects the tape; this not only protects the pinch roller but prevents you from leaving the tape in place when you park the car, thus eliminating the possibility that the tape will jam your stereo if it warps in the hot sun. Many recent decks have auto pause instead of auto eject. At shutoff, or when you press the pause button, this feature disengages the transport from the tape but leaves the tape in place. Therefore, you can restart the tape just by pushing the play button rather than having to push the cassette back in. This is a convenience-but it probably still pays to remove the tape entirely when parking in the sun.

Not all tape features affect tape motion. Some (especially tape equalization, noise reduction, and azimuth adjustment) affect the fidelity of the sound. The equalization selector, usually labeled "Metal/Normal," matches the playback to the 70-µS equalization generally used with metal (Type IV) and chrome (Type II) tapes, or the 120 uS equalization normally used with ferric (Type I) tapes. Some modern car players select the proper EQ automatically, by reading notches in the cassette which indicate the tape type.

Noise reduction is basically de signed to combat tape hiss, a high-frequency noise; its effects are plainly audible, even in a moving car, be cause road noise is mainly of low frequency. Four types of noise reduction are common in car stereo (though usually not all four in any one unit): Dolby B, Dolby C, dbx, and DNR. The two Dolby systems and dbx are needed for optimum playback of tapes recorded with those NR systems; you'll want to have the same NR system in your car deck as you use when making tapes at home. Unlike the other three, DNR can be used on any tape (or radio broad cast, for that matter).

Dolby B NR, found on virtually every home cassette deck and used on most commercially duplicated cassettes, amplifies hissy high frequencies in re cording and reduces them by an equal amount in playback, simultaneously diminishing by up to 10 dB any high-frequency noise which may have been added to the original signal. If your car stereo lacks Dolby NR decoding, it can still play tapes made with Dolby B NR if you turn down the treble control. The frequency response will be slightly off, but the sound will still be passable.

Dolby C NR, whose popularity is growing rapidly, reduces high-frequency noise by up to 20 dB and reduces midrange noise as well. But tapes made with Dolby C NR must be played back on decks with Dolby C decoders. Otherwise, they will sound shrill. Similarly, if you make tapes with the dbx noise-reduction system, then you must play them back through a head unit which has dbx decoding (which quite a few car-stereo units have), or the tapes will sound unpleasantly compressed and a bit shrill.

The DNR system consists of a high-frequency cutoff filter whose action varies with the high-frequency content of the playback signal. When the signal's high frequencies are strong enough to override noise, the DNR filter opens up to let those highs through.

When the signal's high frequencies are weak enough for noise to become audible, the DNR filter clamps down, to cut off the high-frequency noise. The DNR system can be used in conjunction with other noise-reduction circuits.

A small but growing number of car-stereo units now correct or compensate for azimuth errors. When the play back head scans a tape at a different azimuth angle than the recording head did, the mismatch causes high-frequency losses. This problem is especially common in car-stereo units because they only play tapes recorded on other machines, which increases the probability of mismatch. Also, a given tape's effective azimuth will change according to its direction relative to the cassette shell; therefore, the many car stereos with automatic tape reverse face different azimuth angles for each direction of play. And the bouncing and vibration which mobile equipment is subject to can shift the heads slightly, making azimuth problems likely to increase over time.

Several ear-stereo units compensate by adjusting the playback head's angle. In most cases, the adjustment is preset to compensate for the difference in azimuth between forward and reverse playing directions. A few models can be manually adjusted, by ear, to compensate for any azimuth error (even errors due to misaligned recorders), and at least one model corrects its azimuth automatically, while the tape is playing. Another approach is to leave the playback head alone but boost the high-frequency response enough to compensate for azimuth losses; this too must be set by ear.

With two possible exceptions, specifications mean exactly the same thing when applied to car-stereo components that they would mean if applied to home equipment. The two exceptions, power and tuner sensitivity, may or may not mean the same as they do in home-component spec sheets, de pending on how they're stated.

When you see a car-stereo amplifier's power specification given in full, to 18 kHz, at 0.5% distortion, you can assume it means the same thing that the same spec would for a home amp.

The only difference is that the car amplifier's rating will be given in terms of the power it can deliver into 4-ohm speakers, rather than the 8-ohm loads used in rating home amps-quite legitimate, as almost all car speakers have 4-ohm impedances.

However, be skeptical when any of those details are omitted from the specs. If no power bandwidth is listed, assume the power rating applies only at 1 kHz, with somewhat less available at the ends of the audio frequency band. If no distortion figure is specified, assume that the power is measured at an un-listenably high 10% distortion. And if the spec does not list power "per channel," assume that the figure given is for the sum of all the channels, not just for a single channel.

That can be especially deceptive if, as is often the case in car systems, the amplifier has four channels instead of the usual two-not for quadraphonic use, but to power the front and rear speaker systems independently. With out all of these formal technical specifications, the 20-watt amplifier de scribed above could be listed as delivering 120 watts or more!

Tuner sensitivity figures in dBf mean the same thing in car and home tuners, but sensitivity figures in uV are not equivalent, due to different antenna impedances. Thus, a sensitivity figure of 20 dBf would be given as 2.75 uV if measured across a car tuner's 75-ohm input but 5.5 uV if measured across a 300-ohm input, as is commonly done for home tuners.

----------------

---Stereo units with knobs at each end and the tape slot and tuning indicator

jutting from the middle (A) fit the dashboard spaces in most older cars

and many newer ones. The dashboard spaces in more and more new cars, however,

are rectangular, DIN-standard slots for which flat-front units (B) are

designed. Note the station indicators: Pointer-and-dial (A) vs. digital

readout (B). The digital display panel of the unit shown here flips down

for access to the cassette slot and subsidiary controls.

---- Equalizers with up to seven bands are still simple enough to be used

as extra-versatile tone controls.

-------Complex equalizers should be set up by a competent installer, preferably

with the aid of test instruments, and then left alone. Such equalizers

are often mounted in the trunk to discourage fiddling.

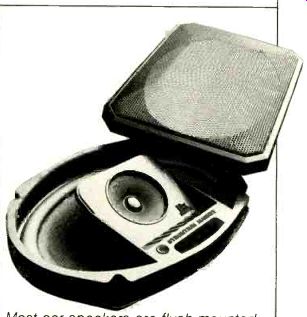

------ Most car speakers are flush-mounted in holes cut into the car's

interior panels. Since oval speakers are usually mounted in the shelf behind

the back seat, some models (such as the Coustic HS-892, shown here) tilt

the tweeter up to aim it more directly at the listener.

------------------

EQs, Amps, and Crossovers

Equalizers are more common in cars than in home systems. In theory, they're being used to overcome the sonic problems of the car's interior and the limitations of car speakers and speaker placement-tasks the usual five-band car equalizer, with controls for both channels ganged together, is ill-equipped to handle. In practice, all too many listeners simply set the top and bottom controls full up, so they'll always hear bass and treble even if they seldom hear what the music really sounds like.

If your sound true, then you should probably rework that system, if you can afford it, until equalization is no longer necessary. Equalization can help, but only about as much as aspirin helps a bro ken leg. Any equalizer with enough flexibility to deal with your system's problems would have more controls than you could cope with while driving;

elaborate equalizers which can handle such problems are usually designed to be set up by professional installers and then hidden away.

If you want to use an equalizer as a tone control, the fewer controls the bet ter. This is one reason why five-band equalizers are the most popular type for car use. However, we find that a three-band equalizer is even easier to use and is still as versatile as one could wish.

Amplifiers come in two types, power amplifiers and boosters. The main difference is that power amplifiers are built to work from the weak, preamp level output signals of the more expensive head units, while boosters require the heftier outputs of the small amplifiers built into lower priced receivers.

Boosters are basically designed for after-the-fact expansion of basic systems. The power increase available from boosters is often limited but is still significant; the chief problem is that the booster also amplifies whatever noise and distortion may have been added to the signal by the receiver's amplifier stage. Some power amplifiers include both booster-level and preamp-level inputs; you can use such an amp to expand a simple system now, then re use it later as the nucleus of a more advanced, higher powered system.

Electronic crossovers route bass and treble frequencies to different amplifiers. They are far more common in cars than in home systems, and are often built into equalizers or amplifiers.

Bi-amplifying-using separate amps for bass and treble-allows the use of a powerful amplifier for the bass, which needs it, and a less powerful amp for the more delicate midrange and tweeter drivers, which could be damaged by too much power. It also ensures cleaner sound; if the woofer amp is overdriven, its distortion will be con fined to the woofer, which can't repro duce the higher and more annoying Since the correct crossover frequency to use depends on the particular speakers (and, to a slight extent, on the acoustics of the particular car), most electronic crossovers allow this frequency to be adjusted during installation. Some even allow the low-pass frequency for the subwoofer and the high-pass frequency for the rest of the system to be adjusted independently.

In complex car systems, the amplifiers and crossover are frequently mounted on an amp rack in the trunk or elsewhere. This usually simplifies wiring and service, while giving the owner visible evidence of what he has when he feels like showing off. It can also make the components more visible to any thieves who happen by when the trunk is opened; for this reason, some installers conceal their amp racks be hind removable panels.

Speakers

------ When woofers and tweeters are mounted independently, the installer

can put the woofer where there's room for its large magnet and mount the

tweeter where its highs can best be heard. Next to the speakers is a crossover

network which routes highs to the tweeters and lows to the woofers.

Choosing speakers for a car is far different from choosing them for home use. Most home speakers are built into enclosures when you buy them. Be cause space is so limited in a car, speakers must usually be flush-mounted in doors or other body panels.

Therefore, most car speakers are naked drivers, without enclosures of their own. To conserve space, such speakers are usually coaxial types, with the tweeter mounted in front of the woofer.

Systems with independently mounted tweeters and woofers, however, some times allow more choice of placement, with the woofers mounted where they'll fit and the tweeters where they can face listeners most directly. The woofer and tweeter should be within a few inches of each other for most natural sound; a speaker whose woofer and tweeter are mounted on a flat plate will ensure this.

Self-enclosed mini-speakers, some times mounted on rear decks or slung beneath dashboards, can be used where it's inadvisable to cut large speaker holes. They also solve a problem for the speaker designer, who never knows for sure what enclosure volume will be behind his flush-mounted speakers; with self-enclosed speakers, he can optimize the design for a known enclosure volume.

Speakers should be placed and aimed so that passengers can hear the more directional high frequencies; treble is lost if the highs are aimed at the car's upholstery or the passengers' socks. This is often easier said than done, however. It helps to have both front and rear speakers so that sound can reach front and rear passengers at equal levels. (Fader controls on receivers and equalizers are used to adjust the front/rear balance.) Otherwise, the passengers farthest from the speakers will hear clearly only when the sound is loud enough to curdle the ears of passengers closest to the speakers. Rear-deck speakers usually have an easier time delivering deep bass than front-mounted ones, because larger speaker drivers can be located on the deck and because deck-mounted speakers can use the trunk's large volume as an enclosure. However, front-mounted speakers usually give a more natural impression, since we usually face mu sic we're listening to.

The best values in car speakers tend to be two-way (woofer/tweeter) or three-way (woofer/midrange/tweeter) systems. Four-way, five-way, and other systems tend to raise cost more than quality, while single-driver systems tend to have limited, poorly directed frequency response.

The car's space limitations make it hard to fit speakers that are large enough to deliver good bass into locations where their upper frequencies can be heard. So, to get low bass in the car, it's easiest to delegate low frequencies to subwoofers, which can be tucked into the trunk or elsewhere.

With such a setup, the low bass will be coming from behind the listeners, while most other frequencies will come from in front of them. The lower the frequency at which the sound crosses over from the main speakers to the sub-woofer, the less you'll notice this; the subwoofer's location becomes least obtrusive when the crossover frequency is below 100 Hz. On the other hand, the higher the crossover frequency, the smaller the main speakers can be, which makes them easier to place.

Still, in no case should the crossover frequency for a rear-mounted sub-woofer be above 250 Hz. Some manufacturers offer components with built-in crossovers at about 2 kHz, well into the midrange. A 2-kHz crossover is acceptable when the tweeter and woofer are close together. But with front tweeters and rear woofers, the musical effect is like having your soup in front of you and your spoon behind.

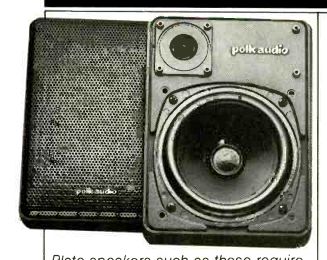

---- Plate speakers such as these require the cutting of only one

hole in the car body panel for the woofer magnet.

The tweeter mounts in front of the body panel, not in it.

Car interiors tend to resonate at about 150 Hz, making the upper bass too prominent. Installers frequently stagger their crossover frequencies in order to leave a response dip between the subwoofer and upper-frequency speakers, thereby underemphasizing the frequencies that the car's acoustics will overemphasize. This only works, however, if the frequency at which the dip is needed is the right crossover frequency for the speaker drivers involved. If not, it's better to correct the car's acoustical problems with equalization.

Installation

Installation is usually best done by professionals. The car is a cramped and awkward place to work, and the tools required are not found in most home workshops. 'Also, it takes a good deal of knowledge to place speakers where they'll sound right and where they won't interfere with window cranks and other mechanisms, and to install the electronics so they won't pick up noise from the car's electrical system.

That's not to say you can't install your own system, especially if it's a simple one. Many people do-but most of them do it only once or twice, and then leave it to professionals thereafter. (We speak from experience here.) It takes research to find the best installers in your area. Go by their reputation, by the sound quality and craftsmanship of the installations they've already done, and by their understanding of your needs. Make sure, too, that you and your installer know exactly what results you want and how they're to be achieved, and get a fairly firm estimate of what the installation will cost you.

If you plan to buy equipment yourself and then take it to an installer, make sure he'll go along with that. Many installers won't touch equipment that they're not familiar with, and quite a few won't install equipment that they didn't sell. For a complex system, it might pay to choose your installer first and work with him to pick a system, rather than picking the system and hunting for someone to install it.

If you're buying a new car, check the sound systems offered by the factory.

Since the success of the Delco-GM/ Bose system ("Roadsigns," Audio, December 1982), some car manufacturers have moved towards producing premium sound systems of their own; the first of these we've heard, the Ford JBL system ("Roadsigns," Audio, November 1985), is at least as good. If you're considering a factory-installed system, make sure you hear a demonstration before buying, preferably in the same model and body style as the car you're ordering.

Car-stereo prices may seem high, at first. But while $500 or more for one little box and a couple of speakers may strike you as costly, it may seem more reasonable when you itemize what you've bought as an AM/FM tuner, amplifier, cassette deck, speakers, and a custom installation. More elaborate systems, of course, cost more: $1,000 to $2,000 for a system is not unheard of, and we've heard systems up to $5,000 or so that were worth the money--at least to those who had it to spend. As usual, diminishing returns set in at some point, where every cost increase brings less sonic benefit than the preceding one. Some of that cost may go for cosmetics (such as concealing equipment), and some may go for alarms and other security measures. In very high-priced systems, a lot of money may go for mindless multiplication of components; the phrase "16 speakers per channel" sounds far more impressive than the resulting system does! How good a system you're willing to buy will depend on your tastes, your income, and the amount of time you spend in your car.

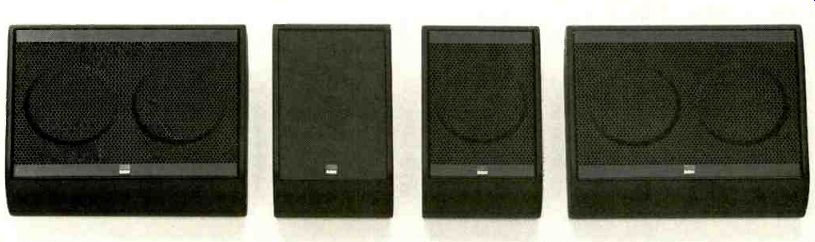

---- In this modular B & W system, the woofers mount in the trunk,

feeding bass through hoses to the large grilles shown. The tweeter module,

with its smaller grille, can be surface-mounted on a body panel or flush-mounted

in a hole cut into the panel. The small module without grille is a crossover,

which can be concealed.

(adapted from Audio magazine, May 1986)

Also see:

The Problem with FM (March 1985)

Antennas FM -- Try a Rhombic FM Antenna (Jan. 1982)

= = = =