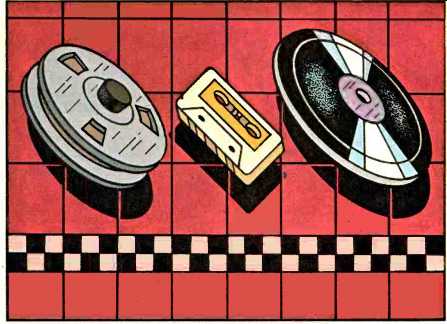

For many years now, audiophiles have lamented the fact that phonograph records

and prerecorded open-reel and cassette tapes have been the limiting factor

in their quest for realism in the reproduction of music. To their way of thinking,

their high-fidelity sound equipment was infinitely superior to all commercial

formats of recorded "software." Of phonograph records, they complained

about the lack of wide frequency response and wide dynamic range. Fortissimo

passages were over-cut and full of distortion. Physically, the records had

various forms of warpage, eccentric center holes, and steady-state surface

noise, as well as pops, ticks and assorted sonic hash. If their prerecorded

open-reel tapes gave them somewhat wider frequency response and dynamic range

than discs, it also gave them print-through, interchannel leakage, and the

accursed omnipresent tape hiss. As for the lowly prerecorded cassette, no self

respecting audiophile would ever consider it a high-fidelity medium.

Now in 1981, audiophiles who own the very best high-end playback equipment have relatively less justification to malign recorded software. For the most part, music software has not only caught up with high-quality playback equipment, but in many cases has severely taxed the capabilities of such systems. What follows is a sort of "state of music software" report, and there is such a diverse selection there is almost an embarrassment of riches.

Despite many of the controversial aspects of digital sound (many of the more far-out audiophiles purport to hear such anomalies as "high frequency glare" and "graininess," and "compression" of perspective and ambience), more and more record companies are issuing analog phonograph records made from digitally recorded masters. In addition, many of these companies are lavishing extra care and stricter quality control in the production of these records. High-quality disc-cutting techniques, including half-speed mastering, plus precision electro plating and the use of special vinyl formulations for high-quality pressings are commonplace.

With the exception of London/Decca Records, which has its own proprietary digital recording system, most record companies have not elected to adopt an official digital recording system but are using a number of the systems now available. The Soundstream digital system has been used by Telarc, RCA, Philips, Varese/Sarabande, Chalfont, Digitech, Delos, and quite a few other companies. The 3M digital system has been used by WEA, CBS, DGG, and others.

Sony has digital credits with CBS, Philips, M&K, DGG, RCA, and others. JVC has the newest professional digital recording system which thus far has been used by EMI, Capitol, Nonesuch, Vox, and Smithsonian Institution Recordings.

Half-speed mastering, with its purported gains in quality, is the special province of Mobile Fidelity records, and now they have been joined in using this technique by CBS Mastersound recordings. The special qualities of dbx-encoded records can be had from such record labels as M&K, Sarabande, Chalfont, Vox, Nonesuch, Ultragroove, and others.

Sheffield Labs and Crystal Clear still hold up the banner for direct-to-disc re cording. The AudioSource Company can supply special high-quality imported recordings from Japanese Philips, Proprius and Lyricon. The audiophile seeking high-quality recordings can also often find gems in the regular catalog output of London/Decca, EMI, Philips, and Deutsche Grammophon.

Open-reel prerecorded tapes still have their loyal supporters, and the Bar clay Crocker people keep faith with them. The quality of their duplications is at a very high level indeed, and with their newly acquired rights to the Philips catalog, there are some superb recordings from this company.

Prerecorded cassettes have come a long way from the efforts of a few years ago, but then so have the cassette players. The level of quality in this medium is most largely dependent on a high degree of synergism between cassette and player. One thing certain is that there is no lack of variety in prerecorded cassettes. So-called standard cassettes, usually issued on a normal ferric oxide tape with 120-uS equalization, are avail able on a regular basis from CBS, RCA, DGG, Philips, and London/Decca. Audiophile cassettes are issued on chromium dioxide tape with 70-uS equalization. Usually some attention is paid to better construction for the shell, and duplicating speed ratios are less than the standard 64 to 1; in the case of the CBS Mastersound cassettes it is 16 to 1. Both Mobile Fidelity and In Sync prerecorded cassettes are duplicated on a one-to-one or real-time basis. Prerecorded cassettes using metal-particle tape are a relatively recent development, and they are now available from JVC, which duplicates these cassettes at a 16-to-1 ratio, and from Audible Images, which duplicates their cassettes on a one-to-one real-time basis. In another new development, dbx encoded cassettes are available from Ultragroove, Sarabande, M&K, Chalfont, and several others. Certainly, all the foregoing discs and tapes constitute a pretty impressive array of what is available in high-quality recorded software.

Let's take a closer look at some outstanding recordings from each category. In digital/analog hybrid discs, Telarc continues to issue some generally impressive recordings. A case in point is their DG10054 of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring, with the Cleveland Orchestra conducted by Lorin Maazel. There are about a zillion recordings of this orchestral tour de force, and on balance, at least in matters of sound, this is the best.

The spacious acoustics of Severance Hall in Cleveland give a nice warmth to the strings and woodwinds, but don't excessively soften the contours of the brass and percussion which are so important in this score. Dynamic range is as wide as you can put on an analog disc, and some of the thunderous climaxes combining tympani and bass drum are awesome in their impact.

Maazel does all of the necessary things in his performance, but if it lacks a bit in thrust and verve, the splendid playing he elicits from the Cleveland Orchestra makes up for this. Still in the category of digital/analog hybrid discs is a real rouser from Philips.

They used the Soundstream system to record the Boston Pops with its new conductor John Williams. Side one of 6302082 contains classical material with, alas, the great "Orb and Sceptre" march of William Walton taken at such a breakneck tempo that it loses all its majesty. The album is entitled Pops on the March, and the second side has some of the great numbers the Pops does so well. "The St. Louis Blues March" and the "South Rampart Street Parade" are cleverly arranged and played with great zest, and the sound will knock your socks off! The recording is of the close up highly detailed variety, but they have managed to preserve the splendid acoustics of Boston Symphony Hall. Wide dynamic range here as well as room-rattling fortissimos.

From London/Decca come two digital/analog hybrid recordings of tremendous impact that are definitely in the "don't miss" class. One is LDR10015 of Shostakovich's Symphony #7 (Lenin grad) and the Age of Gold Ballet by the London Philharmonic conducted by Bernard Haitink. The utterly clean sound is very wide in dynamic range, and the heaven-storming climaxes of the frenetic first movement will leave you limp! The other production, LDR10031, is of Bruckner's Symphony #5 by the Chicago Symphony conducted by Georg Solti.

Not only does this recording have a wide dynamic range, it has a very high-level output. This is very useful in the great Brucknerian brass chorales in many parts of the score. You have never heard such brass! Simply overwhelming, and the rest of the recording is on the same elevated plane.

If you want a foretaste of what true digital recording may sound like, try some dbx-encoded discs. You will need a dbx decoder like the $109 Model 21 or the more versatile Model 224 (it can encode dbx as well as decode) at $279 I'm sure you all know that the dbx is a compander 2-to-1 and 1-to-2 system which affords 30 dB of noise reduction and a dynamic range on their encoded disc of more than 90 dB. If there is by chance some residual noise on the master tapes that are dbx encoded, it is possible to hear the noise being modulated, although the effect is more noticeable on some types of music than others. With discs encoded from digitally recorded masters, there is virtually no noise. In fact, it is uncanny with some of these, dbx-encoded discs that start off with a loud vigorous declamation from the orchestra and then sort of "lunge" at you from a background of dead silence. Two really spectacular dbx-encoded discs are The Empire Strikes Back on Chalfont SDG313 and Boy With Goldfish on Sarabande VCDM 1000 30. Both were re corded with the Soundstream digital system, and when you say wide dynamic range here, you mean 90 dB. In fact, while some of the fortissimos here are quite awesome (in particular Boy With Goldfish affording some of the most stupendous bass drum ever put on a record), it is the extreme pianissimos with a total lack of noise that are the most intriguing aspects of the discs. As to the report in some quarters that the dbx decoder attenuates bass, a single listen to these discs will put that story to rest and will also refute the claim made by some that ambience information is diminished. These discs will stress any sound system to the utmost.

As to how prerecorded metal cassettes sound, on the evidence of JVC MDS-7 Mountain Dance with Dave Grusin, the answer is just splendid. The Dolby B encoded tape is quiet and the sound pristine clean, with especially sharp "punchy" transient response.

High-frequency response is especially well maintained, which is one of the things you would expect with metal tape.

Well, there you have it. Try any of the recordings in the various mediums mentioned above, and you will find much that will please you from the technical viewpoint in the present state of the art in software.

-----------

(Adapted from: Audio magazine, Jun. 1981; Bert Whyte )

= = = =