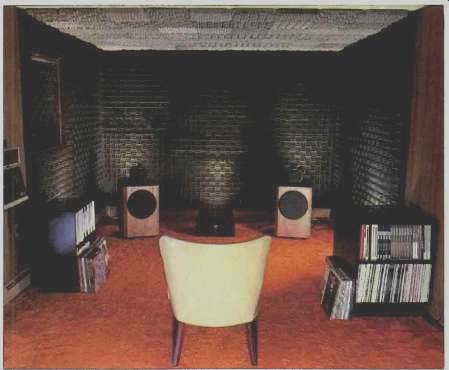

above: Bert Whyte's listening room, in which sound-absorbing Sonex was used in an LEDE installation.

Most audiophiles, even those who are relatively inexperienced, learn early on that the catch-phrase "concert hall realism" is much abused and indiscriminately applied as a quality achieved by almost all hi-fi equipment. Or so the copywriters would have you believe. The audiophile is aware that what he ultimately is trying to achieve is the closest simulation of the live listening experience, whether the music be of the pop persuasion or from the vast resources of the classical repertoire. To this end, most audiophiles continually upgrade their systems to achieve ever higher levels of sonic sophistication.

Some truly dedicated audiophiles spend large sums of money improving their systems. Unfortunately, the acquisition of expensive stereo equipment is no guarantee that the elusive sense of realism will be secured. I have heard some absolutely awful sound from some of the most expensive components. Almost invariably, the poor sound was not the fault of the equipment (although quality can vary widely even in expensive units) but in the manner in which the system was set up and, most especially, the acoustic environment in which it operated. For some strange reason, even experienced audiophiles with high quality stereo systems do not regard the acoustics of their listening rooms as a vital element in playback of music. Too many audiophiles look upon room acoustics as a most arcane subject, and their knowledge of it is at best rudimentary. They admit to a continuing feeling of frustration in their efforts to improve the simulation of the live listening experience.

But there is a new way of acoustically treating listening rooms to achieve this purpose, far beyond what audio equipment can achieve on its own. My awareness of it began at an AES convention several years ago. I was roaming around the exhibits and ran across Alpha Audio of Richmond, Virginia, a company unknown to me. The genial president of the company, Nick Colleran, introduced me to the product they were displaying, an acoustical material known as Sonex. Sonex is an open-cell polyurethane foam supplied in 4 x 4 foot charcoal gray sheets, in 2-, 3-, and 4-inch thicknesses. It is configured in what is called the "indented" or female pattern and the "wedge shaped" or male pattern. (You have probably seen the wedges used in anechoic chambers, and the wedge pattern of Sonex is the same, although the wedges are on a much smaller scale.) Sonex is also supplied in 15 x 15 inch, 2-inch thick wedge-shaped "audio tiles" in silver, blue, brown, orange, and green. Because of the wedge pattern, one square foot of Sonex has 450% more surface area than a square foot of flat foam, and there is almost 100% absorption from 500 Hz to 1.5 kHz with the 4-inch thick Sonex.

Nick Colleran told me about the use of Sonex in recording studio control rooms, in a rather radical configuration known as "live end-dead end" (LEDE) and promulgated by Don and Carolyn Davis of Synergistic Audio Concepts in California. Traditionally, most studio control rooms have their monitor speakers mounted near the front wall and ceiling boundary, surrounded by reflective walls. The mixing console is in the front third of the studio, where the mixer can face the monitors, usually no more than 10 feet in front of him.

The rear side walls and the rear wall are ordinarily made as absorptive as possible. Hence, the "live" reflective end of the control room is in the front, and the "dead" absorptive end is in the rear. Although many aspects of studio control room acoustics are quite controversial, a number of engineers feel the Davis' LEDE approach, in which the "live" end is in the rear of the control room and the "dead" end is at the front of the room, has some unique advantages. Not the least of these special qualities is the very uniform absorption characteristics of Sonex.

When the walls and ceiling of the front of the control room are covered with Sonex, both the absorption and the wedges work together. The wedges provide surfaces to interrupt and break up standing waves so that any energy that might be reflected is diffused. The absorption comes into play along with the diffusion to prevent close-order early reflections which, if the Sonex were not present, would reflect off the hard live wall and combine out of phase with the direct sounds of the monitor. This would produce nasty comb-filter effects, with subsequent frequency anomalies. With the elimination of the close-order early reflections, the mixer hears just the direct sound of the monitors and is not influenced by room acoustics.

After discussing some of the professional studio applications of Sonex with Nick Colleran, I had a brainstorm. It occurred to me that there should be no technical reasons why Sonex would not work in an LEDE configuration in a home listening room. The different circumstances might require some modifications, but I didn't think they would be too difficult. Nick agreed at once and said that as soon as I measured my room and knew the requirements, I could start construction of the first residential LEDE listening room.

First came some basic choices. With orange carpeting in my 12 1/2 x 24 foot listening room, I decided the standard charcoal Sonex would make an attractive color contrast. I selected the 3 inch thick Sonex because it is definitely superior to the 2-inch, especially in the lower frequencies, and is almost on a par with the 4-inch thickness, without its bulk and greater expense.

As a rough rule of thumb, the front dead end of the room should be one-third of the room's total length-in my case, 8 feet. My ceiling height is also 8 feet, so it worked out very nicely to use four of the standard 4 x 4 foot sheets of Sonex on each side wall, and six of the same sheets on the back wall. The 6-inch space was pieced in by cutting strips from another Sonex sheet. For the ceiling, I chose the light silver-colored 15 x 15 inch "audio tiles," both for the desirable color contrast and ease of installation as compared to handling large sheets over one's head! The live end of my room is wood-paneled. Diffusion and the avoidance of long path lengths which would accentuate standing waves are provided by record cabinets on each wall and rear speakers (for use in ambience recovery, ambisonics, etc.). If you undertake construction of an LEDE room, it would be worthwhile to look into several other matters before proceeding. For example, how structurally rigid is the room? Large unbroken areas-the ceiling, floor, and perhaps the walls too-are subject to diaphragmatic "flexing" which can accentuate certain room modes and cause boominess and muddy, over resonant bass. Because of the flimsy nature of most ceilings, nothing much can be done to avoid excessive flexure. However, the Sonex "audiotiles" will afford a little help because of their absorption and diffusion properties. I am fortunate that my listening room is on a concrete slab. In most homes, especially those of recent construction, wooden floors are prime sources of flexure. If your playback equipment is in the listening room with your loudspeakers (the usual arrangement), such floors can be troublesome sources of structure-borne feedback.

One partial solution is to run a 2 x 6 piece of lumber diagonally under the floor joists. This can be held in place and exert upward stiffening pressure by means of one or two adjustable support columns lowered or extended by a worm gear.

Walls can also benefit from stiffening. Dennis Lockhart of Charlotte, North Carolina, built the second residential LEDE listening room. His room dimensions are almost identical to mine and his construction is essentially the same. To stiffen his walls, Dennis cemented together two 3/4-inch, 4 x 8 foot sheets of high density particle board and used enough of these fabricated sheets to do the job. The 1 1/2 inch thick particle board and its weight exerted just the right amount of pressure. There still was some flexure, but the resonance was changed and room modes were better damped for a cleaner bass. If a room is on a concrete slab and the paneling is heavy enough so that it can be screwed and glued to the studs, the spaces between the studs can be filled with dry beach sand.

Next month I'll detail the finishing of my LEDE listening room, report on its performance, and discuss some of the ramifications of this new technique.

-----------

(Audio magazine, Jun. 1982; Bert Whyte )

= = = =