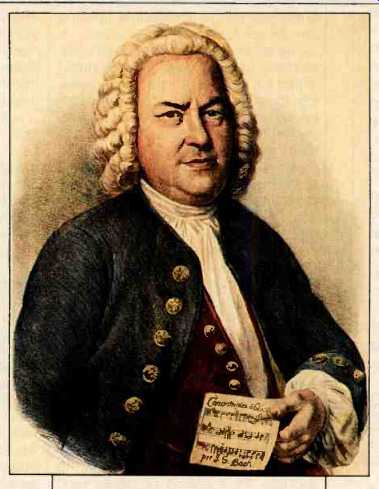

HEARKENING BACH

The 300th anniversary of the birth of Johann Sebastian Bach was celebrated on March 21, 1985. To mark the occasion, National Public Radio station WGBH in Boston arranged for an all-digital uplink and downlink, via Intelsat satellite, of a performance of Bach's "St. Matthew Passion" from the Gewandhaus in Leipzig, East Germany. The program was also made avail able to other stations in the NPR network.

Obviously, this was an historic broadcast, emanating as it did from behind the Iron Curtain. Of course, it was entirely appropriate, considering the years Bach spent as organist and music director of the St. Thomas Church in Leipzig.

I have had an abiding love for the music of Bach ever since I was a 12-year-old choir boy and sang many of his glorious cantatas. In my life, I have been privileged to know, and to record, some great Bach scholars.

I was most profoundly influenced on the music of Bach by my long association with Leopold Stokowski. Although the popularity of Bach's music has been increasing ever since its "rediscovery" by Mendelssohn, surely much credit must be given to Stokowski for his tireless efforts in bringing Bach's music to a wider public awareness. His famous transcriptions of Bach organ works for full symphony orchestra, as exemplified in the great "Toccata and Fugue in D Minor for Organ," are legendary. When he performed this work in the Walt Disney film Fantasia, he introduced millions of people to the glorious music of Bach.

I remember many occasions in Stokowski's Fifth Avenue, New York apartment when we would discuss Bach's music. He liked to point out (some times by playing snippets of recordings) how the magnificent architectonics of Bach's music were so appreciated by musicologists, but that the essential beauty of the music was what endeared it to so many people.

Another Bach scholar I recorded was the great cellist, Pablo Casals, surely one of the most passionate advocates of Bach's music. At the Casals Festival in Puerto Rico, I recorded Pablo and Alexander "Sasha" Schneider, the famous violinist, conductor of the Casals Festival Orchestra, and another ardent champion of Bach's music. I recorded Pablo performing the Dvorak cello concerto, which, sadly, turned out to be the last time he was able to play a full concerto. I attended a number of Pablo's "master classes" just to see the grand old man in action, and I heard how he inevitably turned to the music of Bach to demonstrate techniques to his cello students He would not dwell on the structural complexities of Bach's music, but on its sheer musical values-all the while exhorting his students to play cantabile--"Your instrument must sing!" One activity in which the saintly Pablo Casals did not participate was a rather uninhibited farewell party at the conclusion of the aforementioned festival in Puerto Rico. Held at the Rockefellers' Dorado Beach Club, it was a combination luau, barbecue and fiesta, with fabulous food and exotic tropical potables. As the party became more bibulous, Jesus Sanroma, the well-known concert pianist (whom I was later to record in Gershwin's "Rhapsody in Blue," with William Steinberg conducting the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra), had someone support him from behind while he leaned backwards on the piano stool and played the piano with his bare feet! During all this, he was accompanied by Sasha Schneider, who was playing some outrageously schmaltzy Gypsy violin music! I have many anecdotes about amusing incidents during recording sessions-may be I'll tell you them one of these days. I hasten to add that making recordings is a serious business, with a great deal of strain and pressures and responsibilities. There is always that big "taxi meter" (musicians'-union fees) inexorably ticking away! However, I don't subscribe to the starched, white lab coat Tonmeister attitude, replete with grim visages.

I've always found that with a relaxed and happy session there is a much better chance of making a good recording.

Another concentrated exposure to Bach's music came when I spent some time with Walter Carlos, creator of Switched-On Bach. In his lab/studio, Walter went through the incredibly complex and difficult process of using his synthesizers to construct Bach's magnificent musical edifices. So much electronic manipulation for each small increment of music! Although Walter was obviously deeply involved in the architectonics of Bach's music be cause of the very nature of the synthesizer process, he has always had a most profound respect and scholarly attitude for the purely musical aspects of Bach's works. Even those who are disdainful of the synthesizer process, per se, admit that some of the performance values of Switched-On Bach are consonant with accepted practices in live music performance.

I think it all boils down to the concept that whether Bach's music is per formed on a flute, a harpsichord, a synthesizer, or a kazoo, it is still the music of Bach. After 300 years it re mains transcendently beautiful, cerebral if you will, as emotionally uplifting and as spiritually exalting as ever.

The special broadcast of Bach's "St. Matthew Passion" was digitally transmitted via satellite. It would be interesting to know whether the more hide bound anti-digital people denied them selves the pleasure of hearing this historic performance just because the music was subjected to that "awful digitizing"! Don't laugh! At the last two Consumer Electronics Shows, I saw some well-known members of the anti-digital corps walk into a demo room, note that the only music source was a Compact Disc player, and, sniffing disdainfully, immediately walk out! Well, everyone is entitled to their own opinion. However, I do feel that the anti-digital types have some misconceptions. For one thing, just because someone likes the sound of digital recordings doesn't mean that person is automatically anti-analog or that he can't abide black vinyl records! As far as I am concerned, I am less interested in the medium, and more concerned with how the recording sounds--be it analog or digital--and whether the musical values are properly preserved and presented.

I still like and enjoy good analog recordings. Lord knows, I've got a helluva lot of them! I'm fortunate enough to own many 15-ips, Dolby A first-generation master-tape copies, and I'm sure not ready to abandon them! I also have many 30-ips, two-channel, half-inch master tapes which are real gems! But if a given piece of music is available on a really good digital Compact Disc recording, it has virtues with which an analog version of the same piece can't possibly compete.

Flexibility-that's the name of the game, and not a cop-out! Those who remain steadfastly anti-digital are put ting themselves into a technological straitjacket. Why? For the simple reason that major record companies are recording virtually all of their classical music in digital format. Except for a tiny trickle of new analog recordings from small, independent companies, usually small-scale stuff with minor or unknown artists, digital is all there is! Even the most vociferous anti-digital types are aware that, for several years now, most black vinyl discs have been mastered from digital tapes. Thus, if they want analog, they will have to re sign themselves to older recordings, many of which will go out of print.

Scare tactics? Not at all. Just ask any major classical record producers if they are still making analog masters.

Is there any way to resolve this problem? I'm afraid it would be difficult, at best. Let's put it this way: If I were going to record a major symphony orchestra-the New York Philharmonic, for example-I would probably employ a simple, spaced array of three omni mikes, or a Blumlein or M/S setup feeding a basic, two-channel digital recorder. I would simultaneously set up a Calrec Soundfield microphone feeding a four-channel digital recorder so as to have a "surround" master in the can for future use. In spite of the possibility of deriving a binaural pair from the Soundfield mike, I would also set up the new Bruel & Kjaer dummy head (originally designed by Mercedes Benz for their own acoustical testing) with B & K ear-canal mikes. This array would be fed into another basic, two-channel digital recorder to provide pure binaural recording. This would finally allow Walkman-type cassette deck users to hear music specifically recorded for headphones with the proper acoustic perspective. Finally, I would feed my basic spaced array or Blumlein mike setup into a two-channel, half-inch, analog tape recorder operating at 30 ips. These various setups would be used simultaneously and be covered by the basic musicians'-union recording fees.

Needless to say, making a separate analog master presupposes that a record company is willing to accept a "double inventory" situation. Based on past experience, this is not likely to happen. About all that could be hoped for is that a company would agree to make the special analog records avail able at a premium price, in the same fashion as higher priced audiophile recordings. Conceivably, these special analog records could turn a profit.

Jack Renner and Bob Woods of Telarc will hate me for saying this, but their company-with its simple miking philosophy, high-quality recording techniques, and roster of major sym phony orchestras and artists-would be a likely candidate for the preservation of analog recording.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Bert Whyte)

= = = =