A NOVICE APPROACH

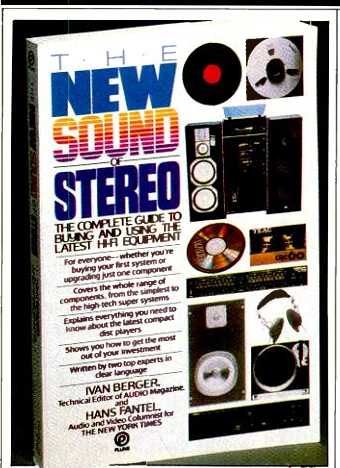

The New Sound of Stereo by Ivan Berger and Hans Fantel. New American Library, paperback, 265 pp., $12.95.

In The New Sound of Stereo, Ivan Berger and Hans Fantel have gathered together all of the knowledge that first time hi-fi buyers need. Armed with such wisdom, beginners should be able to go bravely forth into the shops, avoid most of the pitfalls, take home a good-sounding system and perhaps even save some money. But the book goes farther than that, covering topics such as how to place speakers in a listening room, how to plan for future upgrades, and how to shop later for additional components that will extend the basic system. Berger and Fantel also discuss how to integrate video sound into an audio system.

No, you won't find detailed explanations of Thiele/Small parameters, nor probing surveys of exotic speaker cables. What's here is just the basics, straight from the shoulder. Still, even experienced audiophiles might find some of the information useful. Have you forgotten what a dBW or a femtowatt is, or how to troubleshoot a system to find the component that needs repair? This book truly delivers on its prom se to be jargon-free. To explain the technical concepts behind audio in clear, easy-to-understand English is not always easy to do, but Berger and Fantel succeed wonderfully. A glossary would be a nice addition to the second edition. However, terms are well defined in the text, and the well-organized index points to them clearly.

Another strong point is the book's emphasis on listening. Understanding technology is one thing, but knowing what it means in actual sound is quite another. Berger and Fantel encourage readers to trust what their ears are telling them, and offer guidelines about listening to hi-fi gear. Frequently, they raise the beginner's objection: "My ears are untrained, so my perceptions are not worthwhile," and beat it back by saying that you'll learn to recognize your new system's virtues and its vices after you buy it, so why not acquire some listening skills first, to minimize those vices?

Always, their advice is tempered with common sense. In discussing how to listen to speakers, the authors urge you to listen to the bass, but also point out that too much bass reveals a defect in the design. A powerful amplifier is desirable, but too much power can be a waste of money; of course, too little power leads to other kinds of problems. They quickly debunk the beginner's notion that a speaker with more drivers in the cabinet is always better than one with fewer drivers even to the point of extolling the virtues of the theoretically ideal one-way system. Unfortunately, despite giving much attention to left-right speaker imaging, they neglect depth of image, which is one of the really interesting ways speakers differ from each other.

In the chapter on cartridges, Berger and Fantel cover all the principal topics, including stylus geometries, tracking, and groove structure. With dry humor, while discussing compliance, they appear to explain the units of measurement, but actually do not:

"Compliance is usually expressed by a measurement such as '10^-6 dynes/ centimeter' (or pascals per milli-newton, which amounts to the same thing)." In other words, don't worry about the strange units of measurement; what a beginner needs to know is whether a low or a high number is better, and why. Berger and Fantel don't explain why cartridges affect the sound of a system as much as speakers do. Early in the book they allude to the idea that transducers have the greatest effect on the sound of a system. But they don't nail it down and advise the consumer to shop for a cartridge as carefully as for a speaker.

The authors observe that open-reel tape recorders are better than cassette recorders. Clearly, this is more or less true, but I've seen too many consumers who were misled by this oversimplification. A low-end open-reel machine is not necessarily capable of making better sounding tapes than a sophisticated cassette deck at the same price.

They talk extensively about transports, but don't describe how they affect the sound quality. However, I like their orderly discussion of tape types and noise-reduction systems. Probably, not many readers of Audio will think they need this book. After all, it's "just" basic hi-fi information. But we all have friends who pester us with questions. For them, we should keep a copy of The New Sound of Stereo handy. Then we can peek at it in the middle of the night to answer our own questions. Don't let its simple, straight forward language fool you; the book is a handy reference that belongs on every audiophile's shelf.

---Steve Birchall

San Francisco Nights by Gene Sculatti and Davin Seay. St. Martin's Press, paperback, 192 pp., $12.95.

In the mid-'60s, as a few brave souls began trading in their acoustic guitars for electrics, something strange was happening in the already progressive San Francisco Bay area. A new sound, an amalgam of folk, bluegrass, raga, Bach and jug band music, was incubating in garages, back rooms and basements of Victorian houses. It would soon rush headlong into a realm ruled at the time by spike-heeled girl groups, squeaky-clean folk duos and trios, bleached-blond surf stylists and a handful of toned-down black singers.

The authors of San Francisco Nights set the stage for the psychedelic explosion by briefly reviewing the city's early days as a gold-rush boomtown and beatnik haven. They then plunge into the swirling musical waters. While raising the idea that the psychedelic era was ushered in when the pent-up energy of the '50s was dosed with mind-altering drugs, the authors maintain that the scene was created by people who had nothing better to do. Boardwalks, rather than board rooms, sheltered the creative energy which blossomed in the four years covered by the book.

In a style of reportage that lacks chronological cohesiveness, but compensates with a charming exuberance of tone, the authors trace the histories of prototypical groups such as The Beau Brummels and The Charlatans, survivors like The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane, and transplants such as Janis Joplin and Steve Miller. There are also various flashes in the pan, and groups who-like Only Alternative and His Other Possibilities--were too unstable even to record a whole album. Profusely illustrated with publicity photos and snapshots of the era's movers and shakers, SF Nights also provides a scenic side trip into the advertising world of the time. Many concert posters are reproduced, as well as laugh able attempts by record companies to promote their psychedelic artists with band-member look-alike contests and ads lamed by stereotypical jargon.

Concert promotion, however, in the early days of the Fillmore and Avalon ballrooms, was more like throwing a big party. Hardheaded opportunism was blotted out by sheer romance promoters such as the Family Dog organization exhausted their budgets on framable posters, light shows, party favors, fruit, and prizes such as talking mynah birds. To ensure good attendance at their shows in the spring of 1966, the Fillmore promoters would phone every one of hundreds of people in their personal phone books to get the word out.

The authors report that most artists and organizers shied away from the machinery of capitalism. With lines firmly drawn at that time between the establishment and the counterculture, record companies, by making money from art, seemed particularly evil. But eventually, the practicalities of big business swept through the scene like a green tidal wave. The idealistic either sank or rode its crest. The original Family Dog members gravitated to Mexico in a yellow school bus, one of them with the entire working capital for a show that was already booked. The intimate ballroom "happenings," .with their intricate trappings, quickly gave way to civic theater concerts and extravaganzas in sports stadiums. Attention to unromantic details such as con tracts, insurance, upscale advertising and security police replaced concern over party favors. Jefferson Airplane had risked their counterculture status by "collaborating with known commercial interests" and signing with RCA for an unprecedented $25,000 advance.

Other San Francisco groups, encouraged by the Airplane's success and the control they maintained over their product, became less hesitant to cross the line. The Grateful Dead, who thought they were doing fine as a dance band with steady ballroom gigs, eventually signed up with Warner Bros., late in the game, for an experimental lark. During 1967's Summer of Love, Joe Smith of Warner Bros. was commuting to the Dead's house in the Haight to conduct a flurry of scouting and signing.

By 1968, the San Francisco image was being imitated worldwide. SF Nights tours the complementary music scenes in New York, Los Angeles, Boston, Detroit, Chicago and Texas. Even En gland's psychedelic scene, the authors maintain, was essentially a graft of San Francisco, which took root in a London basement dancehall where patrons grooved to the house band, Pink Floyd, from dusk until dawn.

Up until 1967, record sales to the youth market were mostly of 45s; in assembling an LP, artists might pad out a few three-minute hits with filler and sound-alikes. With longer songs (in part developed to accommodate ballroom audiences) and expanded musical concepts, psychedelic music brought about the rise of albums. Almost overnight, there was an onslaught of LPs packed with extended musical messages and bearing a $5.98 price tag. And the new album market gave credibility to the wide-open formats of underground radio, which would slip, by the mid-'70s, into a predictably formulaic AOR programming format.

Although it covers the commercial angles of the psychedelic era with in sight, San Francisco Nights doesn't fail to portray the personal dramas, spiritual underpinnings and naive good will which were its cornerstones. It's an armchair tour that will induce nostalgia in those who were engulfed by it. Held up against the less-than-best elements of today's music scene, it may evoke regret that the psychedelic era dissolved to leave us among a host of pretentious, vapid and soulless con tenders.

--Susan Borey

Principles of Digital Audio by Ken Pohlmann. Howard W. Sams & Co., paperback, 285 pp., $19.95.

Every knowledgeable audiophile will want to have a copy of Ken Pohlmann's Principles of Digital Audio. This book, written in an easy, conversational style, explains nearly every facet of the subject. Pohlmann covers the familiar territory of digital encoding, but he goes much farther than most writers on the subject, exploring such topics as the decoding process, error protection, magnetic and optical storage media, and digital transmission methods.

The chapter on the Compact Disc alone is worth the price of the entire book, particularly because of the section on the inner workings of a CD player. There are also hundreds of diagrams to illustrate and clarify the points under discussion.

This is not the sort of book you would read straight through while curled up in front of the fireplace, but rather the kind you keep handy to answer your questions. To make topics easy to find, Pohlmann has arranged them in a logical progression; the table of contents is a good general outline, and the index is genuinely helpful. The bibliography includes most of the standard works on digital audio and will be valuable to readers seeking more detailed information.

Despite the straightforward, conversational style of Pohlmann's writing, some readers will find that he has assumed a level of technical knowledge that they don't have. Occasionally, un usual terms such as "birefringence" (a measurement to check the flatness of a CD) or "syndrome" (not a disease contracted by bad data) go past without definition or explanation, so you might need to consult a technical dictionary from time to time. For the second edition, a glossary would be a nice addition. However, you can infer enough meaning from the context to get through it if you are persistent. I suspect that Pohlmann, being a college professor, is accustomed to the live interaction of a classroom, where students can ask about terms they don't understand. In a book, specialized language needs to be explained, especially in a relatively new field.

Sams' editors evidently need some courses in basic English grammar. They repeatedly fail to make subject and verb agree in number, and seem defenseless against the run-on sentence. Readers should keep a bucket of periods and upper-case letters handy. These are not matters of style and preference, but are shocking examples of incompetence. All I can say is, grit your teeth and plow through it, because what Pohlmann has to say is worth reading.

The design of the book is crisp and clean, and the boldface subheadings help you find topics quickly and easily. But the failure to coordinate the illustrations with the text is annoying. Why are the drawings always one page ahead of the text? With just a little more thought and care, the production team could have placed most of the diagrams on the same page as the text.

Books on technical subjects can be extremely dry, but this author's subtle sense of humor helps relieve any oppressively technical feeling. For in stance, he warns readers not to experiment with ultra-fast sampling rates, because the energy required might create a black hole. In another place, he uses a budget for a motorcycle trip as a metaphor. The budget contains only three items: Beer, gas, and motels.

The section on rotary-head and stationary-head digital recorders is filled with good information. In the chapter on the Compact Disc, the description of how a CD is mastered and pressed should be fascinating reading to any one who owns a CD player. A section on recordable optical discs will be come more valuable in the future, as the various types of discs (DRAW, WORM, OROM, and who knows what else) start to enter the marketplace.

Principles of Digital Audio is packed with information, and it's worth reading. Don't hesitate to buy it and keep it handy for reference, but let the publisher know how you feel about the text editing.

--Steve Birchall

Beatle! The Pete Best Story by Pete Best and Patrick Doncastle. Dell Publishing, paperback, 192 pp., $7.95.

In the years since John Lennon was assassinated, every childhood friend of Lennon's and every "fifth Beatle" has put pen to paper to let the world know the real story. Pete Best was The Beatles' drummer before Ringo was shuttled in, and one can sympathize with the fellow who sweated out the early days in the German clubs, before audiences were screaming for the Fab Four. (In fact, much of the time Best was with the group, they were the Fab Five, with Stu Sutcliffe on bass. Sutcliffe had a row with McCartney on one of the German gigs and left the group, dying shortly thereafter of a brain hemorrhage.) Many of the facts included here have been documented in one book or another, as well as in Dick Clark's television special, Birth of The Beatles, for which Best served as a research consultant.

Beatlemaniacs keenly devoted to every aspect of the group's career might find this volume of interest, but it provides only a few insights into the group's history. Best's narrative isn't exactly inspired, and most of the time he deals with superficial incidentals how George refused to clean up the evidence of his post-drunken sickness and managed to live with it in his room for quite some time, how the German girls were ever so eager to comfort the Fab Four, etc. The only time you get a feeling for the Best personality is when he recounts being sacked from the group. In a mire of pitiful anecdotes, he belabors the question, "If I wasn't a good enough drummer, why did they put up with me for the years of paying dues and then give me the elbow right after receiving a record contract?" True, Pete Best got the shaft, but how many times should one try to make milk from sour grapes?

----Jon & Sally Tiven

------------------- Bookcassettes

The success of radio drama was due to skilled writing, skilled acting, and skillful use of sound. Radio drama "worked" not just because of what was said, but because of what was left out and, hence, left to the imagination.

Similarly, a good novel relies solely on skillful writing, leaving the reader to fill in the blanks.

Now, the Brilliance Corp. of Grand Haven, Mich. has produced a combi nation of the novel and the spoken drama. On its Bookcassettes, complete books are recorded on cassette, read by excellent actors. The narrative passages are read as one might expect. What is unusual is that dialog is read by actors who can be considered as taking the parts of the characters whose lines they speak.

The dialog is in no way changed, nor are the narrative portions. Nothing is omitted. Likewise, nothing is added, not even sound effects. If the book describes a high-speed car chase, you must supply the sound of the mo tor, the sound of shots, the smell of gasoline, etc. The only liberties which are sometimes taken involve such touches as adding a bit of reverberation if the action takes place inside a church, applying some filtering if we are eavesdropping on a telephone conversation, etc.

The reading is often done at high speed, and this can be a bit disconcerting at first. I found, however, that after listening a while, I became used to it. Further, this brisk pace adds to the tension in adventure novels.

A book can take several hours to read aloud, and if suitable steps were not taken, Bookcassettes would have to be recorded on many cassettes. To solve this problem, Bookcassettes are recorded monophonically, using all four tracks on the cassette. In order to play them, you need a stereophonic player. Begin by setting the balance control so that the left channel is heard. Play the first side of the cassette; turn it over and play the second side. Next, turn the cassette over once more, but now adjust the balance control so that output is obtained from the right channel only, and proceed as be fore, listening to the third and fourth tracks of the cassette.

Program material of this kind would likely be enjoyed by users of personal portable equipment. Even where such players are equipped with a balance control, it is often disconcerting to have the sound produced in just one channel of a headphone. To solve this, the Brilliance Corp. can supply an adaptor to be placed between the player and the headphones. This device has switching which can send a signal from either the left or right channel into both sides of a headphone.

Another interesting technical note is that the folks at Brilliance use digital speech compression to achieve the reading speed, rather than having the actors wear themselves out attempting to maintain such a pace. This writer has considerable experience with speech compression and can usually detect it; I was not able to do so when listening to Bookcassettes.

The Bookcassette packaging is de signed to look like a book, and the price is the same as that of the hard cover printed version. The headphone adaptor costs approximately $2.

These products are available at fine bookstores. For a catalog and additional information, write to: Brilliance Corp., Box 114, Grand Haven, Mich. 49417.

The phone number is (616) 846-5256 in Michigan, (800) 222-3225 elsewhere.

--- Joseph Giovanelli

In One Lifetime: The Life of William Grant Still by Verna Arvey. The University of Arkansas Press; cloth, $16; paperback, $9.95.

William Grant Still was born in 1895 in the deepest South, descended from a slave woman and a Scots plantation supervisor named Still. He was, without a doubt, the first Negro (the term preferred in this book, and common through most of Still's life) to rise in the music world into the "classical" area by virtue of thorough training, and to compose on a professional symphonic scale and conduct major orchestras.

This in itself makes him an important figure in American musical life. Though he long outlived Gershwin, three years his junior, the two lives make an interesting parallel, running virtually side by side in the heady New York of the 1920s-though in Arvey's biography Gershwin's name is never mentioned, among hundreds of well-known musical personalities.

William Grant Still, like Gershwin, immersed himself in the show-biz excitement of post-WW I New York, both as a brilliant arranger/composer/conductor and as a performer on almost any instrument that came along. But oddly, Still's commitment to the classical took him technically far beyond Gershwin, who never really mastered either the required expertise in orchestration or, more important, the structural organization of larger classical forms. Still was a tune-writer of genius, with a marvelous sense of piquant harmonies and rhythms. His larger works are essentially strings of these tunes glued together with ingenious breaks.

As a teenager Still was already studying the basic classical disciplines-counterpoint, harmony and reading-through the scores of Beethoven and even Richard Wagner. Astonishing, one might think, in a Negro youth brought up at the beginning of this century in deepest Louisiana and in Little Rock (of more recent fame in black liberation). But from the very start, Still pursued a classical education, thorough and conservative, even including a stretch at that Midwestern bastion of "serious" music, Oberlin College.

Where Gershwin's genius kept him in the living theater, right on through Porgy and Bess, William Grant Still (who also wrote operas) was thus able to diversify into a surprising variety of musical entertainment, from Eubie Blake's traveling Shuffle Along, full of future black stars, to much success in radio, arranging for big-time network shows, and on to major symphony orchestras and worldwide recognition.

This last did not imply a rejection of black values-far from it. Still went the opposite way, to bring classical dignity and craftsmanship to music with Negro themes. It was a notable aim, and often shocking to those who expected the "primitive" sort of black art.

All of which makes for a powerful range in the subject matter of this biography, in spite of many predictable weaknesses: The author, Verna Arvey, was Still's second wife, a brilliant and well-educated white pianist, writer and interviewer who began working with him when he came to the West Coast around 1934. They were not married until 1939, but their increasing interdependence is clear enough. She could put vast energy into an increasingly complex interracial social life and a growing involvement in music world wide; she also became Still's literary partner, devising texts, fitting words to the shape of melodic lines, concocting entire plots of his operas directly with him. In this book, it is "we" and "our" throughout the second part, and no slightest disrespect or criticism of "Billy" can be tolerated by this strong minded helpmate. A far from totally objective account, understandably.

The theme of racial tolerance, rather than belligerence, runs through the book and can only be praised; it was an ideal for both Still and Arvey. Their case for the dignity of Negro accomplishments is even more persuasive.

But the impetuous Verna is not a good judge; those many great names, and small ones too, who were sympathetic and helpful tend to be made into plaster saints; on the other side, she relates scurrilous plots, real enough, yet tending to blame the ominous "they" and, alas, leaning toward an intolerance that is not too pleasant.

The famous Still benefactors are in variably "foremost composers" and the like, but though they surely were kindly, most of them are anything but foremost in many minds. They all belong to a very conservative, old-fashioned type, which seems to have been where the Stills moved. Atonal music, in contrast, is made by "tin pan clangers," and "modernists" in general are given very short shrift. "Modern music"--a term long outmoded--is senseless jangle and nothing more.

Some will agree, others definitely not.

The first half of the story, before the name-dropping (legitimate but, in the end, boring), is the salvation of his work and explains the rest. The picture of a group of highly intelligent 19th-

century black families, well educated and well mannered, most of them quite literate and often schoolteachers. is quite fascinating, a side of the old Deep South life that seldom reaches us these days. It does, in truth, explain the later William Grant Still in rather moving terms, in spite of the tendency towards plaster sainthood, and is thus a contribution towards both musical and black history.

Incidentally, the entire world of audio electronics and recording of music is virtually ignored here. This is strictly a live-music world, straight through to the 1970s! Not atypical of the professional musician's viewpoint. Broad casting, yes-but only as though it were another show, or a concert.

--Edward Tatnall Canby

(adapted from Audio magazine, Jun. 1986)

= = = =