DEVOLUTION OF THE SPECIES

The evolution of musical instruments over the centuries has been driven by the demands of virtuoso players who have constantly sought greater facility, better intonation, and more acoustical output from their instruments. The modern concert grand piano, for example, evolved out of efforts to produce an instrument that could withstand the demanding technique of Franz Liszt and the other great pianists who followed him. The high tension stringing on a cast iron frame of today's instruments produces considerable tone and is a far cry from the simple design of the early pianoforte.

Today's highly articulated action is miles ahead in its ability to negotiate repeated notes and rapid scale passages. In the symphony orchestra, wind and percussion instruments have continued to evolve, even into modern times, as the players have sought greater facility and the capability of playing louder without intonation (pitch) problems.

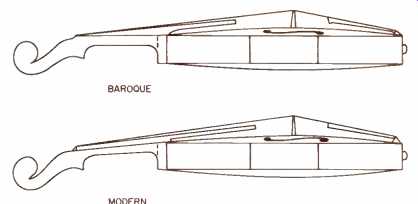

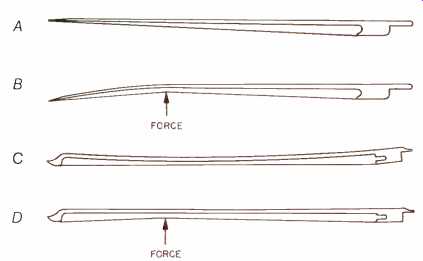

The oldest section of the orchestra, the strings, often includes highly prized instruments made more than 200 years ago. Early in the 19th century, most of these instruments were re built with a steeper neck and finger board that could support a higher bridge and, consequently, higher tension stringing (Fig. 1). The curve, or crowning, of the bridge top (not visible in this side view) was also increased so that violinists could play more vigorously without accidentally touching two strings at once. The emergence of the violin as a virtuoso instrument, in the hands of Niccolo Paganini and the like, forced such modifications. The instruments have changed little since then, except for the introduction early in this century of wire-wound strings (and a steel E-string) in place of the original gut strings. Even the bow underwent a marked change. Baroque bows were shaped in such a way that increased pressure on the string resulted in "wrapping" the hair of the bow around two or more strings, making it difficult to play loudly without sounding the adjacent strings.

About 1775, Tourte devised a bow with a reverse curve, which caused the hair of the bow to stiffen with increased pressure on the strings, thus allowing the player a greater range of dynamics. Figure 2 shows the basic differences in profile of the older bow as compared with today's instrument.

For most of this century, the works of the baroque masters, such as Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi, have been played on modern instruments, whether on recordings or in the concert hall. On college campuses, collegium musicum groups were often formed for the authentic performance of Renaissance and earlier works, but music of the baroque (1600 to 1750) and classical (1750 to 1825) periods was routinely done on modern instruments.

During the 1960s, the recordings of Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Vienna Concentus Musicus brought to a large base of listeners a degree of authenticity in baroque music via early instruments and scholarship in performance practice. And as the '70s progressed, the so-called "early music" business took off in a big way. Many record labels embraced it, and the number of conductors and ensembles (at least in name) proliferated. Purely from a re cording point of view, these ensembles had the good fortune of benefiting from newer approaches to recording ushered in by the digital era: Direct-to-stereo (two-channel) recording, improved microphones, and the general return to natural perspectives. Most of the groups are European or English, so it was relatively easy for them to identify recording venues appropriate for the program at hand, since the Old World abounds in unspoiled 200-year-old structures.

Record companies have a bonanza here: They have opened up a new branch of music, so to speak. New conductors and players, a fresh look at playing familiar music-this is grist for the record mills at much less than the cost of a major symphony orchestra, and all without the agony of dealing with superstar conductors and soloists, or their agents.

Today, our ears have become so conditioned to the sound of authentic instruments in music of the baroque era that modern instruments seem strangely out of place. No record company today would think seriously about issuing a set of Handel Concerti Grossi or Bach Brandenburg Concerti using modern instruments, no matter what the reputation or competence of the group and its conductor. The competition on early instruments is simply too great, and the performances often do capture an eloquence and spirit hard to duplicate with modern instruments.

There are a few adjustments the listener must make on the way to enjoying period instrument performances.

First, there is the matter of intonation in the wind and brass sections of the ensembles. The suavity of modern wood winds will be missed, and in their place will be somewhat rough-edged sounds of lesser dynamic range and less precise tuning. The brass instruments are, valveless, and as such depend on the player's "lipping" tones, up or down as needed, to place the pitch. These problems in pitch accuracy simply must be accepted as such. The strings are played without a vibrato, and string attacks are apt to be less incisive, due to the lightness of the bowing.

The small size of most early-music ensembles is welcomed in most cases, as are the more modest recording venues. Recording directors often seek out venues which have lots of "bloom," an immediate sense of reverberation and ambience. The venues which work best are often old ballrooms with lots of plaster, wood, articulated surfaces, and coffered ceilings. When vocal re sources are included, the singing style is light, unforced, and most "unoperatic" in the conventional 19th-century sense.

Few standing early-music groups perform regularly in concert. Most of their activity is in the recording studio, and the pervasiveness of their efforts, via FM broadcast and disc sales, is a measure of just how significant the record industry has become in shaping musical tastes. More to the point is the effect on programming of concerts by major orchestras.

An ironic consequence of early-mu sic groups' success is that many sym phony orchestras have simply stopped programming the compositions of Bach and Handel, and other baroque works. This is a musical loss for the audience and may be a downright liability for the orchestra. As conductor Gerard Schwarz pointed out last year in "A Conductor Must Help to Shape Public Taste"-an article in the September 17 issue of The New York Times-orchestras which ignore 18th-century repertoire in favor of 19th- and 20th-century music lose certain ensemble skills which the earlier music reinforces, and general competence may suffer as a result.

This last point is especially of concern at present, in that the early-music forces have embraced music of the classical era. The symphonies of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven are now available in many performances by authentic instrument ensembles, and the fortepiano has made a triumphant return as these ensembles' chosen vehicle for Mozart and Beethoven piano concertos. Pity the modern orchestra that is daunted by this and stops programming Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven! It may be quite a while before most of us are willing to trade in new instruments for old in the classical literature.

After all, we have been so thoroughly conditioned in this repertoire by the great conductors and orchestras of this century, not to mention the legendary keyboard virtuosi who have per formed the concertos. Musicality, not authenticity, is likely to be our chief concern here, even though it is relatively easy to demonstrate that the fortepiano is, in a purely acoustical sense, a better match for a classical size ensemble than is the modern con cert grand piano.

Fig.

1--Baroque and modern violins. Note the higher bridge and slanted neck of

the modern instrument.

Fig. 2--The flat top of old-style violin bows (A) deflected easily when the

bow was pressed against the string, wrapping the bow around the string (B)

and making it difficult to play one string at a time loudly. The reverse curve

of the modern Tourte bow (C) maintains greater tension, so deflection is minimal

(D).

The most venturesome conductor and ensemble on the period instrument scene are, unquestionably, Roger Norrington and the London Classical Players. Having gone through most of the Beethoven symphonies, Norrington and his group issued late in 1989 a period-instrument recording of "Symphonie Fantastique" by Berlioz. The re cording is immensely successful and has moments of considerable insight.

Perhaps the problem most people have listening to it is the preconception that it is a large "Romantic" work requiring resources akin to those common toward the end of the 19th century. The fact is that the work dates from 1830, just barely out of the classical era into the Romantic. The identification of Berlioz as the Father of the Modern Orchestra further confuses our expectations and judgments.

If Berlioz, then why not the early Romantics: Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Schumann? There are no reasons why not, if the motives are right. What about extending the notion forward to period instrument performance of Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Wagner? This is okay if the notion of "original instruments" is tempered to include certain performance values.

For example, Brahms wrote for the so-called "natural" French horn, an instrument without valves. He preferred it for its purity of tone, as compared with the valved form of the instrument.

While there are some expert players on the natural horn, all major symphonic horn players today use the ubiquitous "double horn" version, which has extra sets of tubing and makes for greater accuracy in playing. Would we be willing to put up with split horn notes in Brahms' symphonies for the sake of authenticity? I don't think so-at least not for long.

Perhaps the best way to approach the late Romantic period is to start at the present, analyzing current performance practices and working back ward. If we did this, we would find that modern orchestras play far too loudly.

We would remove some of the wire-wound strings from the violins, violas, and cellos, and we would certainly ask the brass players to tone things down considerably so that the strings could be heard without forcing.

We would take a look at middle-European orchestral practice, which favors a soft-edged approach to sound production and reaches a real fortissimo only once or twice during a typical concert.

We would take note that modern woodwind instruments can play so well in tune, but we would ask them to play still a bit more softly.

We would implore our architects and acoustical consultants to be leery of what Michael Forsyth refers to in his MIT Press book, Buildings for Music, as the Hi-Fi Concert Hall, and return to earlier values.

Finally, we would ask recording engineers and producers to use fewer microphones, do less gain riding and "spotlighting," and strive for the pickup of natural stereo perspectives.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Jun. 1990)

= = = =