Author: DAVID LANDER

above: Stanford student Dolby (third from left) started at Ampex.

Few scientists get to see their names on movie marquees. Ray Milton Dolby does-frequently-and the famous double-D symbol of Dolby Laboratories adorns cassette decks the world over. Indeed, the name has become almost synonymous with noise reduction. The professional Dolby A type NR system, so popular with filmmakers, is becoming part of the TV production scene. More than 70 million Dolby B items for consumers have been produced since that NR system was introduced with open-reel decks in 1968, followed two years later with cassette decks. Currently being shipped or about to go into production are 112 different models of products with Dolby C-type noise reduction.

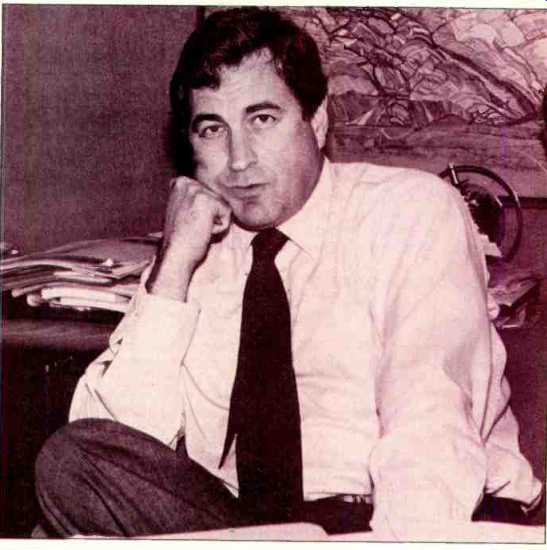

Yet the 49-year-old Dolby, whose career has taken him from the San Francisco Bay area, where he was raised and educated, to England, India and back again, remains unassuming, even shy. He is cautious when it comes to predicting the future of his C-type system. But as the discussion progresses he candidly admits to frustrations with both professionals and consumers who often seem either unable or unwilling to appreciate the sonic improvements Dolby has endeavored to bring to tape recordings, FM broadcasts and films.

-D.L.

According to your biography, you worked at Ampex while attending StanfordUniversity. Did you go to college at night?

No, I was on a normal course, but I had a fairly flexible arrangement at Ampex. I worked about 15 hours a week. I just came in whenever it suited me, sometimes during the day, sometimes at night.

How did this come about?

I met [Ampex founder Alexander] Poniatoff when I was 16 years old. He had hired me to show a film for his mental health society. He was always interested in health things. Following the showing he invited me to see his plant and tape recorder and in due course asked if I'd like to work for him-as soon as an opening occurred. He had only about 25 people then.

You spent six years at Cambridge University in England after graduating from Stanford. What did you pursue for that length of time?

Most of the work I did in Cambridge could be described as a kind of noise reduction effort. I was trying to get information about the concentrations of certain elements in specimens-for example, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen-through the bombardment of the specimen with an electron beam and the analysis of the X-rays that come out. In the X-rays there's a lot of hash and garbage and so on. So for six years I tried to devise various methods of cutting through the hash and getting at the information I wanted.

========

Henry Kloss wanted a recorder running at 3 3/4 ips to be as good as a studio recorder running at 15 ips.

=========

How does this "hash" and extraneous noise show up in X-rays?

In the form of graininess. It would be like a grainy television picture, and I had to devise ways of taking the raw information, analyzing it, unscrambling it in the most efficient way possible so the image was as free of grain as possible.

And you see this as analogous to eliminating tape hiss?

Yes, except that you might characterize what I was doing there as single ended noise reduction. In other words, after-the-fact noise reduction. There was no possibility of encoding the signal ahead of time in order to decode it later.

You also pursued your hobby of tape recording in Cambridge. Were you bothered by tape hiss at the time?

I had my Ampex 600 in very good tune, but still there was this tape hiss problem. I accepted, let's say, the state of the art. The tape hiss was there, and it was disturbing and annoying. To switch from line-in to lineout and hear that tape hiss was very annoying, but it was something you had to live with. Once in a while I would think about the problem, and I remember in Cambridge contemplating this idea. Imagine the signal is 100 or 1,000 times as big as the noise that's causing this trouble. Isn't it ridiculous that such a small quantity can cause such annoyance. There ought to be something you could do about that. Previous attempts had been to squash and expand the whole signal, and it had become a byword that it just didn't work, that the distortions and side effects just weren't worth any noise reduction. It was better to get a pure recording coming back with the noise than to suffer these distortions with some noise reduction.

From Cambridge you went on to India--in 1963. What did you do there?

I was working for UNESCO on a technical aid project. In my spare time, I recorded Indian street musicians. I ran my microphone lines out to the street and used to pay street musicians to come and perform. I also invited them into my house--this was usually prearranged--and they would perform North Indian music. I'd set one room up as a sort of control room, and they'd be playing two doors away. And throughout this time I continued to be bothered by the tape hiss problem. I had formed an idea about a noise reduction system that might just work, but I knew there would be some distortions connected with it. I was calculating these when it just hit me that I could bypass the whole problem by dividing the treatment of the signal into two regimes, mainly this high-level regime with loud signals which I would do nothing to, and have separate circuitry for dealing with the low-level signals. The low-level signal circuitry would cut in only under very quiet conditions where the noise was. That was the key to the problem.

To the problem of building the system, you mean. Not of selling it.

Yeah. [Laughs] I've described the easy part so far.

In fact, after starting your company in London and delivering your first order of A-type units to Decca, isn't it true that you couldn't find another customer in England?

It turned out, to my dismay, that Decca was virtually unique. The other companies said things like, "We don't have noise problems. We adjust our recorders every morning. We use the best tapes." That was quite a contrast with the very eager reception which I'd had at Decca. So I didn't sell anything else in England, and by October 1966, things were getting a bit desperate. The money was running out very, very rapidly.

Didn't it occur to you to come home and try to sell your system to the Americans?

That's what I did! I got hold of the New York studio directory and fired off about 30 letters. And I received back four telegrams. Seymour Solomon [of Vanguard] immediately telexed and said, "We're very interested. Please come as fast as you can and demonstrate this." And John Eargle at RCA sent a similar kind of message. So it was really quite a different kind of picture.

I heard that Henry Kloss, then still with KLH, learned about your system from one of his key executives and reached for the phone and called you immediately.

--------- I've been to so many parties where people will say, "Oh,

you're the guy with the switch. What's it do?"

He phoned me in London on a Friday afternoon in March 1967, and asked, "Have you ever thought of doing anything with a consumer product?" And I said, "Well, yes, in due course, I have that in mind." He then asked, "When are you going to be in the U.S. again?" I said, "Well, I'm due to go to the Audio Engineering Society in April in Los Angeles." And he said, "I really want to talk to you right away. Could I come over to London to see you? How about tomorrow?" I was quite taken aback by this. And he went out and got himself a ticket and flew overnight. I picked him up at the airport the next morning. We spent the whole weekend discussing and speculating on the possibilities. He wanted to build an open-reel tape recorder which was the best. He wanted this recorder to be, at 3 3/4 inches per second, as good as a studio recorder at 15 inches per second, felt uncomfortable about being pushed so far so fast because I knew how far it would stretch our resources, but he was determined, so I agreed to jump in and start the project.

So you started work on your B-type noise-reduction system. How long did it take to complete?

Well, the final touches weren't put on the system until the middle of 1969.

When did the idea of applying it to the cassette format occur to you?

In early '69. I started investigating cassettes even though the slow tape speed seemed to be a deterrent, and I was amazed at how well you could do with a cassette if you really tried. After working with various machines, I came up with a Harman/Kardon CAD-4 as a demo machine. That was all souped up and optimized and used with a free-standing noise-reduction unit which was called the 505. I took the first 505 with me to the Audio Engineering Society together with that pampered CAD-4 in October 1969. I stopped in Boston and gave Henry Kloss a demonstration, and he was amazed. He had not considered cassettes before. He had founded Advent by then and was very eager to get moving on something, and I decided to give him a license to manufacture a free-standing noise-reduction unit and also a cassette deck. He started on both things simultaneously, and that's what brought about the Advent Model 100 noise-reduction unit and the 101, and then the Advent 200 cassette recorder.

Was there some specific event that occurred or some precise point in time when you knew that your noise-reduction system had become a standard?

No, it was very, very gradual. It was a matter of giving a lot of demonstrations and talking to a lot of people, explaining and overcoming confusion and misunderstandings and misconceptions.

Did you ever dream the system would gain such widespread acceptance?

Yes, I could see that. One thing that was of enormous value to me in this whole venture was that I had seen the same kind of thing happen to my previous work, the videotape recorder which I'd worked on during my early 20s at Ampex.

And that was the first videotape recording system.

Yes, and I designed most of the electronics for that system.

At that early age?

I was 23 when the first videotape recorder was exhibited at the NAB in Chicago.

Had you even graduated from college at that point?

No. That was the work I was doing part time. My Ampex title, while I was still in college, was consultant. I got very good treatment there. I could come in and hand in my latest designs to be built and next time I would come I'd test them, give instructions...

So you really were something of a prodigy. Here you were, still in college, and these people were working with your designs. You weren't just somebody's assistant who went for coffee.

No, but I'd hesitate to use the term prodigy. I was, I think, just a very practical, capable person with my head screwed on. I mean, I knew how to get things done.

Do you feel now that Dolby C is going to be the new standard?

I don't know whether it's going to be a new standard or not. Nobody knows.

A lot of people in the audio industry are predicting it.

People predict a lot of things, but nobody knows. All you can do is try. And hope. Or maybe say they're crazy if they don't take it. But there were all these expectations With four-channel sound, for example... .

What about your HX system? That hasn't been adopted by many manufacturers. Are you disappointed?

Yes. It proved the thesis that you can't persuade people to pay for more quality than they perceive a need for. Also our effort to clean up FM broadcasting has not worked at all. The reason is that most people simply don't care. Most people listen to FM as sort of a background music while they're shaving or whatever, and they don't care about the quality. That was an endeavor that just didn't work out.

Earlier, you said much the same thing about the record companies in England, other than Decca, of course. It sounds like the fact that most people just don't care about quality may have been one of the biggest frustrations you've faced in business.

That's right. For instance, we started work on our movie program in 1970, and it wasn't until about 1976 or '77 that we began to have the feeling that maybe it was going to go. Because throughout those early years, people in Hollywood, in London and in other places would tell us "You're wasting your time. Nobody cares about the sound. They go for the stars or the plot or the ambience of the event: They don't care about the technical quality of the soundtrack."

But you persisted. When was the breakthrough?

People like to point to Star Wars. But, of course, we had various other pictures. So it was just one little step after another, and there wasn't any single breakthrough. But there was a certain turning point in my own mind, which 'I suppose occurred around that Star Wars time. Before then I didn't know whether I was pouring money down an endless hole; it was really an article of faith up to that time. I thought there had to be some people out there who'd care what it sounds like to hear a good movie soundtrack, and I was going to try long enough until I proved it one way or another. In other words, movies just barely made it. FM radio did not quite make it. It's like the A system. It just barely made it because somehow or other there were just enough studios who said, "Well, I don't know. We don't really have a noise problem, but on the other hand, if we had a gadget that would reduce noise a little bit, I guess that would be handy."

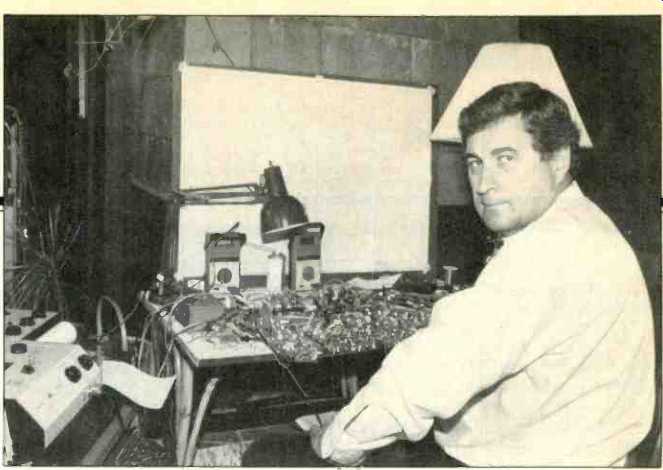

------- At the bench, scientist and engineer Dolby is caught between

those who demand even better NR and people who never hear noise.

Do you think of yourself as a man who just barely made it?

[Pause] That's really what it is. You know, the cassette, before noise reduction was applied to it, did not quite make it as a quality recording medium.

Okay, B-type noise reduction was enough to just barely push it over, and so it did make it. But then there were certain rumblings of dissatisfaction even with the results with B-type. You know, the people who were the real audiophiles, the enthusiasts, they said, yeah, B-type is probably okay for the mass market, but we want something better.

So you're caught between the audiophiles, who want perfection at any cost, and the average listener, who might not want to pay for any noise reduction system at all.

That's why I'm cautious when I say I don't know whether C-type will become a new standard or not. Because the average listener hasn't heard tape hiss with or without noise reduction.

I've been to so many cocktail and dinner parties where people will say, "Oh, you're the guy with the switch. Tell me, what does that switch do, anyway?" And I'll say, "Well, it reduces the hiss." "Hiss," they'll say. "I've never noticed any hiss."

(Adapted from: Audio magazine, Jul. 1982)

Also see:

Introducing Dolby S-Type Noise Reduction (Jun. 1990)

Dolby B-Type Noise Reduction System (Sept. 1973)

The DNR Noise Reducer: How it Works and How to Build it. (Feb. 1985)