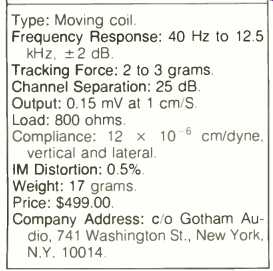

Manufacturer's Specifications

Type: Moving coil

Frequency Response: 20 Hz to 20 kHz +/-1 dB

Vertical Tracking Force: 2.0 to 2 5 grams.

Channel Separation: Greater than 25 dB

Stylus: van den Hul Type I, vertical line-contact, 85 microns.

Compliance: 8 x 10^-6 cm dyne.

Output: 0.115 mV

Optimum Load Termination: 3.0 ohms.

Weight: 6.3 grams

Price: $1.095.00.

Company Address: c/o Audio Classics, 727 Creston Rd., Berkeley, Cal. 94708.

When I first saw the van den Hul Type I moving-coil phono cartridge, it looked as if someone had decimated an EMT cartridge. It certainly looked like nothing I had seen in the past. I asked what had happened to the EMT XSD-15, and was politely informed that this was the new van den Hul Type I phono cartridge-the familiar EMT had been stripped down to the "bone" and reworked almost totally into the finished product I was looking at. I was further informed that the genesis of this cartridge actually goes all the way back to the early Ortofon SPU-GT. And that was a bulky phono cartridge! A number of years ago, A. J. van den Hul had developed a new stylus design and decided to try it on the EMT phono cartridge. In not too long a time, he had almost totally rebuilt the EMT to meet his needs by installing a new stylus design, crafting the cantilever of boron and modifying its length, and optimizing the angle for mounting the new stylus. The relatively bulky body was removed to help eliminate various spurious resonances. It undoubtedly will be of interest to the audiophile to compare some of the original specifications of the EMT phono cartridge, presented in Table I, against the specifications of van den Hul's Type I, which are listed at the beginning of this report.

When all of his other modifications had been accomplished, van den Hul found that the cartridge coils needed to be modified to reorient the lead-out wires and make certain at the same time that the coils were correctly positioned for minimum distortion. Finally, it was necessary to retune the suspension of the cartridge by repositioning the elastomer of the suspension mechanism and physically manipulating it to linearize the frequency response.

About two dozen other changes have been made; one wonders where the original EMT cartridge went, since so very little of it survives. Mr. van den Hut considers the Type I phono cartridge, incorporating all that he knows on the subject, to be the acme of phono cartridges currently available. By the end of this report, the reader may deter mine for himself if Mr. van den Hul has succeeded. In the meantime, I can tell you that as a result of the design modifications, the user should exercise great care to prevent damage to this cartridge. It is sensitive to certain factors in the environment, as outlined in the "Use and Listening Tests" section of this review, in designing stylus tips, the designer must always consider and use as his reference the currently used V-shaped cutting stylus, whose two sides form a 90 deg angle. The front of the cutting stylus is flat and is perpendicular to the lacquer during the cutting process.

The edge of the cutting stylus is slightly rounded, usually having a radius ranging from 2 to 4 microns. The shape of the playback stylus in an ideal situation would be identical to that of the cutting stylus. But, then, each time a given record was played, a new groove would be cut over the existing groove, enlarging it to some degree and worsening the tracking, ad infinitum. Thus, the stylus designer is faced with the problem of developing a stylus tip which would reduce the wear of the record groove to near zero, reduce distortion to an absolute minimum, and maintain a solid contact at the stylus/ groove interface while playing the most difficult and hard-to-reproduce musical passages present on a record. Obviously, such a perfect stylus tip has not been commercially available. Within the past few years, A. J. van den Hul has developed a stylus tip that appears to be nearly perfect and not too distant from the usual cutting stylus shape, namely, a front-to-back radius of 3.5 microns and a rather long vertical groove contact radius of 85 microns (extended line-contact tip). One of the more important aspects of this unusual tip shape is that it is capable of tracing an 85-kHz signal, cleanly.

(Further discussions relating to the van den Hul stylus may be read in Audio, November 1981, page 62.) The output of the van den Hul Type I phono cartridge is quite low; therefore, a step-up device is needed to raise its output voltage to a level that can be used with the usual preamplifier phono input stage. Some preamplifiers have pre-preamplifier phono input stages that may be used with low-output moving-coil phono cartridges. Unfortunately, in my experience, such pre-preamplifiers leave much to be desired. Their main problem is noise. I have tested the van den Hul Type I moving-coil phono cartridge with the a.c.-powered Audio Standards MX-10A pre-preamplifier, which proved to be an excellent combination, also tested it with the Audio Interface CST-80L (3 ohms) step-up transformer, which is ideal for this specific purpose, as it provides maximum energy transfer without de grading the sound of the cartridge. Both of these step-up devices are used in my lab as reference devices.

Since the van den Hul Type I moving-coil phono cartridge is supplied with its own pre-preamplifier, including an outboard power supply, I used this active device for all the tests and listening evaluations. I found it to be among the best active devices I have ever used in my laboratory.

The van den Hul moving-coil phono cartridge comes encased in a black box bearing van den Hul's facsimile signature across the top of the box and the van den Hul name printed on one edge. The box does not indicate which specific van den Hul phono cartridge model it contains. The cartridge is supplied with the usual assortment of mounting screws and a removable stylus guard. Also included is, in my opinion, one of the most important tools needed for installing a phono cartridge-a bubble spirit-level, which weighs only 1.03 grams. I have used such a lightweight bubble spirit-level for many years to ascertain if a phono cartridge is level in the left-to-right and front-to-back planes when the stylus is in contact with the record-groove wall.

For accuracy, I compensate for the weight of the bubble spirit-level when determining the optimum tracking force for the phono cartridge. A frequency response curve for each of the cartridge's channels is also included. However, I have been unable to accept these curves, because they are made with the CBS STR-140 RIAA pink-noise acoustical test record. On this disc, the pink noise is recorded with the standard RIAA recording characteristic, which simplifies its intended use in checking out loudspeakers, their placement in the room and the room itself. But cartridge measurements made with it will include the effects of any errors in the preamp's RIAA equalization. It is common practice throughout the world to measure a phono cartridge's frequency response using a sweep signal that has a constant amplitude from 40 to 500 Hz and a constant velocity from 500 Hz to 20 kHz. I did measure this cartridge's response using the CBS STR-140 pink-noise test record, in conjunction with a very accurate, RIM-equalized preamplifier, to better than + 0.25,-0.5 dB.

For the official record, however, I also followed standard practice and measured the frequency response of this phono cartridge using the CBS STR 100 test record.

Measurements

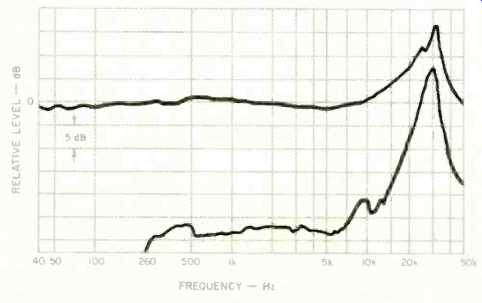

Fig. 1 Frequency response and separation. Note that curve extends

to 50 kHz.

The van den Hul Type I phono cartridge was mounted in a Technics headshell and used with the Technics EPA-A250 (S-shaped) interchangeable tonearm unit attached to the Technics EPA-B500 tonearm base and mounted on a Technics SP-10 Mk II turntable.

The Type I was oriented in the head-shell and tonearm with the Dennesen Geometric Soundtracktor.

Laboratory tests were conducted at an ambient temperature of 74.3° F (23.5° C) and a relative humidity of 66%, ±3%. The tracking force for all reported tests was set at 2.25 grams, with an anti-skating force of 2.3 grams.

The Type I phono cartridge should be used in medium- to high-mass tonearms. The load resistance at the phono input was 47 kilohms, and the load capacitance was 250 pF. As is my practice, measurements were made in both channels, but only the left channel is reported (unless there is a significant difference between the two channels, in which case both channels are re ported for a given measurement).

The following test records were used in making the reported measurements:

Columbia STR-100, STR-112, and STR 120; Shure TTR-103, TTR-109, TTR 110, TTR-115, and TTR-117; Deutsches HiFi No. 2: Nippon Columbia Audio Technical Record (PCM) XL 7004; B & K QR-2010, and Ortofon 0002 and 0003.

Frequency response, measured from 40 Hz to 50 kHz using the CBS STR-100 and STR-120 test records (Fig. 1), was: +0.75.-1 dB from 40 Hz to 700 Hz; ±2 dB from 1 kHz to 15 kHz; +3.5 dB at 15 kHz; +6.5 dB at 20 kHz; + 14 dB at 30 kHz; +3 dB at 40 kHz, and -0.5 dB at 50 kHz. Separation was 29 dB at 1 kHz. 22 dB at 10 kHz, 22 dB at 15 kHz, 14.75 dB at 20 kHz, 6.5 dB at 30 kHz, 16 dB at 40 kHz, and 18 dB at 50 kHz. From this data it is noted that the van den Hul Type I has an excellent frequency response through 20 kHz and a very good high-frequency separation through the same range. The frequency response and separation beyond 20 kHz, though present, is not remark able. The rise in the frequency response beyond 10 kHz is typical of most moving-coil phono cartridges.

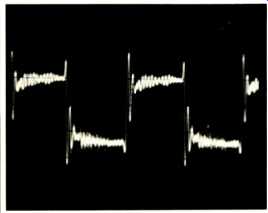

The 1-kHz square-wave response (Fig. 2), using the Columbia STR-112 test record, is consistent with that seen for just about all moving-coil phono cartridges, where a large overshoot is followed by a low-level ringing which de cays rapidly.

From the 1-kHz square wave (Fig. 2), it is evident that the ultrasonic resonance frequency is at about 33 kHz.

This was confirmed when the frequency response curve was extended to 50 kHz. A resonant frequency above 20 kHz usually introduces intermodulation distortion between the ultrasonic noise and the signal, thus producing difference tones which are in the audible range. The sonic result is generally a slightly distorted midrange, with the sound between 3 and 7 kHz having a sort of metallic quality, reduced definition, and a blurring of the stereo image. The resonant frequency also causes large phase shifts in the audible range, with a definite effect on the stereo imaging-a common problem with all moving-coil cartridges.

To measure the arm-cartridge low-frequency resonance, it was necessary to disable the arm's anti-resonance unit. The arm-cartridge low-frequency lateral resonance point for the left channel was 12.5 Hz with a 6-dB rise, while for the right channel it was 12.5 Hz. also with a 6-dB rise. Vertical resonance was at 10.5 Hz. The high frequency resonance was at 33 kHz.

Using the Dynamic Sound Devices DMA-1 dynamic mass analyzer, the arm-cartridge dynamic mass was measured as 18 grams, and the dynamic vertical compliance as 12.76 x 10^-6 cm/dyne at the vertical resonant frequency of 10.5 Hz. The harmonic distortion components of the 1-kHz, 3.54 cm/S rms, 45° velocity signal from the Columbia STR-100 test record are:

1.12% second harmonic and 0.32% third harmonic, with less than 0.18% higher order terms. The vertical stylus angle measured 22° for each channel, using the CBS Model 3002 vertical tracking meter.

Other measured data are: Wt., 6.94g. Opt. tracking force, 2.25 g. Opt. anti-skating force, 2.3 g.

Output. 0.96 mV/cm/S with the pre-preamplifier, and 19.99 uV/cm/S without the pre-preamplifier. IM distortion (200.4000 Hz. 4-to 1): Lateral (+ 9 dB). 2.1%: vertical ( + 6 dB), 2.3%. Crosstalk (using Shure TTR 109): Left.- 18 dB: right. -27 dB. Channel balance. 0.5 dB.

Trackability: High freq. (10.8-kHz. pulsed). 30 cm/S; mid-freq. (1000 and 1500 Hz. lat. cut). 25 cm/S: low freq. (400 and 4000 Hz. lat. cut). 19 cm/S. Increasing the tracking force to 2.7 g allowed the cartridge to track the mid-freq. cut at 31.5 cm/S; Deutsches HiFi No. 2. 300-Hz test band was tracked cleanly to 67 microns (0.0067 cm) lateral at 12.82 cm/ S at + 7.50 dB and to 55.4 microns (0.00554 cm) vertical at 10.32 cm/S at +5.86 dB.

Fig. 2--Response to a 1-kHz square wave.

The van den Hul Type I was able to track all the various bands through level 5 on the Shure Obstacle Course Era III musical test record except for the bass drum, which was reproduced cleanly through level 4. The level 5 bass-drum note has a peak-to-peak amplitude of 304 microns, or a velocity of 4.9 cm/S at a frequency of 52 Hz.

Similarly, the Type I was able to track all the various bands through level 5 on the Shure Obstacle Course Era IV musical test record except for the harp and flute combination, which was reproduced cleanly only through level 3 before distortion was heard. Here, the flute is played at a level of 8 dB while the harp remains at 6 dB. On the Shure Era V test record, all six levels were tracked without mishap. It is a rare commercial analog record that has peak recorded velocities exceeding 15 cm/S, and thus the van den Hul Type I would undoubtedly be able to track all records without any noticeable mis tracking, except for, on very rare occasions, passages in audiophile records from Telarc, Sheffield, or Reference Recordings.

Table I--Manufacturer's specifications of the EMT XSD-15 cartridge, on which

A. J. van den Hul based his Type I.

Use and Listening Tests

The design modifications embodied in the van den Hul Type I have rendered it sensitive to various environ mental factors. Because this cartridge is open, it should be kept away from magnetic particles and any ferrous materials that could be attracted by the powerful magnet and damage the stylus-cantilever assembly. It should also be dusted frequently. To overcome the possibility of damage to the cartridge motor assembly and the stylus, I do not recommend cleaning the internal structure with any sort of brush. I used compressed air (gentle pressure) to blow the dust and dirt away. I suggest cans of compressed air, like those sold at camera shops for cleaning lenses.

The Type l's open construction also makes it, I find, more temperature-sensitive, and I suggest that, for peak performance, it be used at ambient temperatures between 72° and 77° F (22.2° and 25° C).

After the optimum tracking and anti skating force was determined for the van den Hul Type I, I played various types of records for a period exceeding 10 hours (as is my practice) prior to performing laboratory measurements.

The equipment used in the listening evaluation included the aforementioned Technics arm and turntable, the Audio-Technica AT666EX vacuum disc stabilizer, a Crown IC-150 preamplifier, two VSP Labs Trans-MOS 150 amplifiers (each used in the 300-watt mono mode), and B & W 801F loudspeakers.

The speaker cable, Distech, and inter connecting cables were from Discrete Technology ( 2911 Oceanside Rd. Oceanside, N.Y. 11572).

I have lived with the van den Hul Type I moving-coil phono cartridge for quite some time, playing the gamut of recorded music from my record library.

Except for the rare occasions mentioned above, I have not come across any recorded music that the Type I could not reproduce as intended. Son is clarity was excellent, as were the transparency of sound and the transient response. Bass was sonically well defined and more than adequate.

The human singing voice and the piano (the Bosendorfer in particular) were reproduced exceptionally well. Applause definition was excellent.

Having used different moving-coil cartridges fitted with the van den Hul stylus, it was very evident that this stylus shape reproduced details in the upper midrange very accurately. This was particularly evident with this cartridge when playing the superb Cantate Domino (Proprius Records 7762), where the choral passages were re produced without the blurring I have noticed in the past. Continued listening brought out the fact that the van den Hul Type I did not introduce any sound or coloration.

During my listening evaluation, I compared two analog records with their CD versions, where both were derived from the same digital master tapes. On J. S. Bach's Orgelmeister werke (Helmuth Rilling, organist, Denon OX-7027-ND PCM on LP, 38C37-7039 on CD), I was pleased to note that the Type I reproduced this digital-analog recording very accurately, as it did Stravinsky's "Firebird" Suite ( Atlanta, Shaw, Telarc LP DG-10039 and CD-80039).

Some of the other exceptionally good recordings I used in auditioning the van den Hul Type I were: Vivaldi's The Four Seasons ( Boston, Ozawa. Telarc DG-10070). Respighi's Pines of Rome and Fountains of Rome ( Chicago. Reiner, RCA Red Seal Point 5 ATL1-4040), Solid Gold at the Bosendorfer (Tibor Szasz, Sonic Arts Laboratory Series 16), Late Night Guitar (Earl Klugh, Mobile Fidelity MFSL 1-076). Symphonie Fantastique by Berlioz ( Utah, Kojian, Reference Recordings RR-11), Dabs (Reference Recordings RR-12), and The Sheffield Track Record ( Sheffield Lab. 20). The last three are superb recordings and will give your audio system a real workout.

After more than 75 hours of listening to this cartridge play practically everything and anything, I concluded that the van den Hul Type I is undoubtedly one of the best moving-coil phono cartridges available to the audiophile today.

-B. V. Pisha

(Audio magazine, Jul. 1984)

Also see:

Van Den Hul Type III Phono Cartridge--Auricle (July 1984)

ADCOM Crosscoil XC/VAN DEN HUL Moving-Coil Phono Cartridge (Equip. Profile, Jan. 1982)

Supex SD-900/E Moving-Coil Phono Cartridge (Sept. 1975)

A Clutch of Cartridge (Adcom, Grado, Talisman and Decca) (Feb. 1986)

Decca London International Tonearm & Mk VI Gold Elliptical Phono Cartridge (Aug. 1979)

= = = =