As any observer of the consumer audio scene is aware, the current recession

in our national economy has wreaked considerable havoc in the audio components

industry. Across the country, many of the smaller, inadequately capitalized

audio dealers have gone bankrupt, victims of drastically curtailed sales of

stereo equipment. Consumers have restructured their priorities, with the purchase

of audio components relegated to a minor position. As the recession has deepened

and with the imposition of severe restrictions on credit buying, even the bigger

component dealers (including some well-known chains) have had to seek financial

relief by entering into Chapter XI negotiations. As I write this, the Summer

Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago is just a couple of weeks away, and it

is being widely regarded as a "make or break" affair that will determine

the current economic health of the entire industry.

I have recently returned from the 66th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society in Los Angeles, and it is gratifying to report that while there has been a moderate slowdown and some retrenchment in the world of profession al audio, there is no comparison to the ills that have befallen the consumer sector. Oh, there may not have been the jaunty air of confidence and enthusiasm of other years, but in fact, the Los Angeles convention was as usual the biggest yet with more exhibitors than ever. However, it must be noted that apart from the expected activity in digital audio matters, there seemed to be fewer pieces of new equipment than one would have anticipated from the number of exhibitors present.

Early on at the convention, one of the main topics of conversation was the joint announcement by Sony and Studer/ReVox that they had reached an agreement to support a common format in fixed-head digital audio recording. Studer will have access to Sony's digital tape recorder technology, and presumably there will be an interchange of information on Studer's R&D efforts in digital audio. The two companies expressed the desire that their common digital recording format be accepted in the industry as an international standard. In other words, this joint endeavor is an attempt to establish, at least, a de facto standard. Other than the fact that the proposed format utilizes 16-bit linear encoding with multiple sampling rates (apparently 44.056 k, 50.4 k and 55 k) applicable from 2 to 48 (!) channels with new "high efficiency" codings for error protection and "high density" recording, no further information on the format was forthcoming. While the quest for digital audio recording standards is certainly laudable, most spokesmen for other digital tape recorder manufacturers I talked to were not bubbling with enthusiasm and said they would reserve opinions and judgments until the Sony/Studer format is fully de tailed to them. Sony and Studer are powerful organizations with great technological resources, so we will watch with interest the new developments from this unexpected alliance.

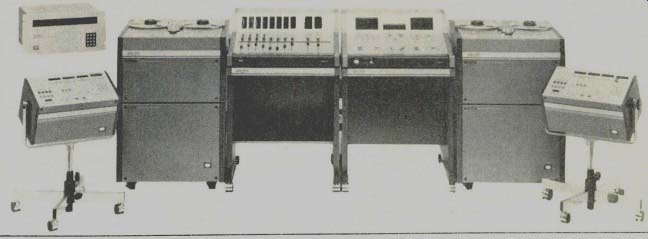

-------- Digital audio recording system exhibited by Technics at the AES

Convention.

Digital Recording Systems

In other digital news, if you are an enthusiast for digital/analog hybrid recordings, Dr. Tom Stockham pointed out that his Soundstream digital re cording service has now produced 75 digital recordings. I, for one, didn't realize there were so many available. (Incidentally, Tom's pioneering digital recording of my Virgil Fox and Arthur Fiedler recordings will soon be avail able in the dbx en coded format.) There were also important developments in the digital area from Technics and JVC. Technics introduced the first fully digital recording system. Its elements include a four-channel digital fixed-head recorder using quarter-inch tape at 15 ips. The unit features a further refinement of thin-film evaporated metal heads pioneered by Technics, which permit high-track density with low playback error rate. Each audio channel is re corded on four parallel tracks with new parity check and error correction techniques (16-track total). There are also four analog channels on the tape which were used for a control track, audio monitoring, SMPTE time code, and spare or voice cue. The recorder is a two-piece unit, one section for the tape transport (the by-now-familiar Technics closed-loop system) and servo system, the other section for the signal electronics. If higher multi channel operation is desired, two or more of the recorders can be operated in parallel, synchronized by SMPTE time code. In the complete digital system, one machine is used for recording and another recorder for editing lay out.

The next item in the Technics system is a unique digital editor, equipped with a solid-state memory and a variable rate read-out clock con trolled by an operating knob. Slow-speed playback analogous to that in, regular cut-and-splice editing is avail able through the slow rate read-out of the digital data stored in the memory.

With two memories available to establish "in" and "out" edit points, the operator "rocks the tape" (as in time honored analog fashion) with the control knob until he determines the edit points. The edit points can be pre viewed before execution of the actual edit, and enter and exit mode crossfades are possible for a smooth transition through these edit points. In the demonstration of the editor I saw, it was quite uncanny to hear the edit previews played back from the memory while the reels of the playback and layout tape recorders remained motionless! A digital audio mixer is the next part of the system. The unit can mix up to eight digital signals, down to a two-channel signal, and then divide it into four channels for the digital recorder. Each channel can be panned, and digital reverberation can be added on an outboard basis. The important aspect of this unit is that all signal processing remains in the digital domain.

Lastly, there is the digital delay unit to interface with a disc cutter. Delay time is keyboard controllable from 0.1 to 1.6 seconds, in increments of 0.1 second.

The entire digital system of recorder, mixer, editor, and disc preview uses 16-bit linear encoding with a sampling frequency of 50.4 kHz. Keeping all elements of the system in the digital domain is obviously the way to go. Unfortunately, Technics gave no information as to price or availability.

JVC introduced their Series 90 digital audio mastering system. The recorder here is the familiar U-Matic helical scan video-cassette unit using 3/4-inch cassettes. The recorder is used with the JVC BP-90 digital audio recording processor, a two-channel PCM processor using 16-bit linear quantization and the usual 44.056-kHz sampling rate. It is claimed that the unit has a new high-efficiency error correcting code.

The AE-90 digital audio editor is some what similar to the Technics editor. In the editing setup, there is one U-Matic VCR for playback and another for lay out, plus the BP-90 PCM processor and the AE-90. Recorded music can be monitored audibly at the desired speed in either direction. In the search function, automatic or manual scanning can be used to locate the exact edit point. The AE-90 is said to have an accuracy of 45 microseconds. As in the Technics editor, rehearse preview of the edit is available from the memory, without running the tapes. Crossfade in and out at edit points is also avail able with four increments of time. In addition, JVC has the CD-90 digital audio delay unit for furnishing a preview signal to a disc cutter. At any sampling frequency, delay time can be up to 1.5 seconds in six-millisecond increments.

With input for 16-bit data, the dynamic range of the delayed signal is more than 90 dB. If controlled by an external clock signal, the unit can be operated at sampling frequencies from 30 to 60 kHz. What appears to be missing in this system is a digital mixer, but per haps that is forthcoming. JVC seems to be deadly serious about this system, as delivery is quoted as "late July" of this year. No price given, but rumor has it in the neighborhood of $120,000.

U.S.S. Amplifier

As is usual at AES conventions, the mixing consoles get ever bigger and more complex. Automation is virtually a necessity, as even the most octopus-armed mixer can't cope without it. The huge Neve Necam automated console that was being demonstrated at the convention was purchased by my ever-venturesome friend Bill Putnam for his United Recording studios. Bill's UREI company introduced a brute of a power amplifier, Model 6500. Designed as a high-quality unit with high output power for professional monitor and "road show" applications, this amp is built like the proverbial battle ship. It has modular amplifier assemblies, accessible from the front panel.

Each amplifier module is equipped with a variable-speed cooling fan. The 6500 has a unique conductor compensation circuit (no, Virginia, it doesn't help bad music conductors!), which includes the speaker wires in the main feedback loop of the amplifier and corrects for wire losses in long runs.

With this circuit high damping factors and high peak current capability are maintained. Power output is 275 watts/channel at eight ohms, all the way to 600 watts at two ohms, and in mono bridged mode, a very healthy 900 watts into eight ohms at 0.2 percent THD. Slew rate is listed at 50 V/ NS. The amplifier is just now going into production.

Here and There at AES

Other interesting items that caught my eye while wandering around the exhibits ... Sansui's new "feed-for ward" amplifier, said to completely (!) cancel all distortions at the output stage, is apparently ready for production ... Crown now in production of the Barclay Badap analyzer and the new PZM microphones. In another move Crown is making to further in crease its involvement in professional audio, they will be making a dedicated instrument for the Energy Time Curve (ETC) measurement techniques, the brainchild of our own Dick Heyser, under license from Cal Tech ... How about a 24-channel recorder using two-inch tape, in two portable cases from Stephens Electronics? ... Or Neal-Ferrograph's Model 312 cassette deck, metal capable, sporting the new Dolby HX system, and a nice three-motor, solenoid operated transport ...

Jerry Bruck, that genial importer of the superb Schoeps microphones, had two intriguing items in his exhibit in aid of better quality stereo recordings. One is the UMS 20 Schoeps universal stereo bracket. This $275 device has clamps to accept various Schoeps mikes. By sliding them along a metal bar, adjusting their angles and aligning a series of colored dots, the specific mikes are properly positioned to make stereo recordings according to the Blumlein, XY, MS and French ORTF techniques.

The second item is from Wes Dooley's Audio Engineering Associates in Pasadena, an active MS matrix decoder, the MS38 (distributed in New York by Jerry Bruck). As you may know, in MS stereo recording, the M (mid) pickup is a cardioid mike facing forward to the source, picking up the main overall sound image; the S (side) mike is a figure-eight pattern picking up lateral directional information. The two mike outputs must be combined in a sum and difference matrix (M+S and M-5) to produce conventional left and right stereo signals. By adjusting the relative balance of M and S signals into the matrix, variations of the stereo perspective are possible. This MS technique affords stereo sound with a very natural balance, with precise imaging, depth and instrument localization.

Heretofore, matrix networks with transformers had to be used, with the attendant degradation caused by the iron in the transformers. Hence, the MS technique was not used as much as it deserved. But the AEA MS38 uses modern solid-state circuitry, no transformers, and as I heard it, is an immaculately clean device. A single knob controls stereo perspective, and interfacing with the recording chain is simple. If the tape you are recording has the original MS signals and if the playback is connected to the inputs of the MS38, it will be decoded directly into conventional left/right stereo sound. With most digital recorders being two-channel units (except 3M), these mike pickups are worth any engineer's attention.

Now we'll have to wait until November at the Waldorf in New York for the 67th AES Convention and further digital developments. I can tell you there will be some surprises!

-----------

(Source: Audio magazine, Aug. 1980; Bert Whyte)

= = = =