by EDWARD TATNALL CANBY

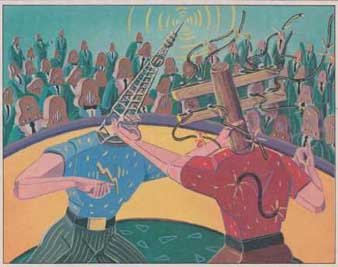

KNOCKED OUT NETWORKS

Last month's discussion of "old band" FM radio in the 1940s was an unofficial segment of my continuing "audio-biography," but so much of the vivid FM background returned to mind that things got a bit out of hand in that respect. If you will consider that the factual account I offer is backed by my own personal recollections, which illuminate so much for me that I did not then understand, I'll continue in the same vein. We might well have had an incredibly different FM right now. We almost did.

It is worth saying again that the early and elegant old-band FM radio broadcasting, from 1939 until soon after the war, was the true start of hi-fi, years before the "component" movement got underway. It was the first real public hifi, if on a small scale. Since last month I've found a lot to bolster that idea in a superb book about FM's great inventor, Man of High Fidelity: Edwin Howard Armstrong, by Lawrence Lessing.

It was published not long after Armstrong's death, but the original 1956 edition was superseded in 1969 by a revised and expanded paperback version, published by Bantam. This revised version takes FM right up to the stereo era, and it is still available through The Armstrong Foundation (1342A S.W. Mudd Building, Columbia University, New York, N.Y. 10027, $1.00 each). It should be intensely interesting for any audio enthusiast with FM in his blood.

To be sure, Major Armstrong's work in radio merely culminated in FM, dating from 1933. Much earlier, and also covered in the book, came those absolutely fundamental radio circuits, the regenerative and then the superhet; with them was that basic audio principle, the amplification of a signal by means of the vacuum tube-a thousandfold, a millionfold, and on. In the end, Lee de Forest, the "audion" tube man, won a battle in the Supreme Court over regeneration, but there isn't much doubt in knowledgeable engineering minds as to who really got there first. (Now don't write Letters to the Editor on that subject! It has been hashed out in millions of words already.) At least Man of High Fidelity suggests that, in the mid-'50s, author Les sing was aware of our newly burgeoning hi-fi biz and not averse to writing for a newly expanding audience, even if the term hi-fi doesn't really apply to Armstrong's earlier discoveries. The title does indeed reinforce my own memory, as of last month, of the extraordinary sonic quality available in that earliest FM. One of my questions is answered neatly by Lessing-how come such remarkable quality in the associated FM equipment, amps, speakers? It was Armstrong himself.

His fingers were into every bit of the developing FM operation; he was fanatical in his insistence on "the best" and in a position to enforce his views, through his FM licensing and his own meticulously detailed personal tests, from studio mikes right through to FM loudspeakers. He worked directly with his manufacturers on all this--no wonder the results were remarkable.

As far as I can now figure, it was in the fall of 1940 that I heard FM for the first time. It came-just about the time the "old band" was allocated-direct from the Major's own station, W2XMN in Alpine, N.J., the one with the big tower across the Hudson. That station went on the air in mid-1939, via one of the five pre-old-band experimental channels. It was a whopper, high power, up in the top range along with the well-known "clear-channel" AM outlets of 50,000 watts and more. And Armstrong worked fast: In that same year he got others to plan a series of similar powerhouse FM stations in other regions, with his very active aid and cooperation; already there were 150 applications for FM stations waiting. For five channels! Under a favorable FCC, television was booted out of just one of its 13 experimental channels, the lowest, making room for FM to expand to 20 channels. Within a year or so there were 500 FM station applications backed up, and more on the way.

New England was a focal point-two of the big 1939 stations began there with a provisional 2 watts, awaiting full power. The Yankee Network set up on a mountain some 40 miles from Boston with its 2 watts and immediately was found to cover the territories of three major AM stations! The same astonishing coverage showed up nearer New York, via an entrepreneur named Doolittle, on Meriden Mountain, which is nicely located between Hartford and Springfield to the north and New Haven to the south, thus blanketing the populous Connecticut River Valley.

With full power, what then? This was real revolution.

Even more important, perhaps, was a favorite new application of FM radio, the microwave directional beam, now familiar to all of us. It was impractical via AM. Static, interference and so on.

With FM it was as good as a hi-fi cable, and cost much, much less for station interconnections. That 2-watt station near Boston, like others to come, was not fed via phone lines, or cable, but by simple microwave, studio to transmitter. Very soon, there was microwave FM from the top of Mt. Washington in New Hampshire.

With all this, why not an FM-plus microwave country-wide set .of networks, coast to coast, and all of top hifi quality at relatively low cost? Marvelous thought! There was terrific enthusiasm for it among those who realized the implications.

That, it seems, was what was in the works, and in a hurry, back just before 1940. It accounted for the pile of FM applications as much as FM's own superior sound quality and noiselessness did. A whole new broadcast setup with a 1940 quality not far from what we have now, even with our satellites and all the rest, the whole laced together via microwave connectors-a series of super-high-power regional FM stations, accurately covering relatively fixed areas. Wow! What an inspiration for those who wanted to get in on the FM ground floor! Don't forget that whereas AM stations on the same wavelength tangle hopelessly (and with those nearby on one side or the other), FM stations ideally do not interfere. It's one or the other, not both. And in those days there were no skies full of jet planes to confuse the FM signal. Remember that the AM networks, in all their vastness, were interconnected mainly via phone lines plus, eventually, the expensively constructed coaxial cable-all these connections on a rental basis. The whole business was ever so neatly bypassed by microwave with FM. Do not suppose, then, that there was nothing but enthusiasm for this exciting changeover to a new and superior radio system! If you know the big-time commercial world, you know what was going on. How about a couple of billion dollars of vested interest on the part of America's largest communications establishments? How about those big operators who rented out their connecting lines at a fat mega-profit? The entire and hugely successful AM radio system at that point was based on the combination of AM broadcasting and the network concept-stations inter linked not via microwave, nor the nonexistent satellite, nor magnetic tape, the same, but guess what? In effect, AT&T. We have no business being critical of this system itself. Radio and long lines phone-company hookups had grown together after only a dozen-odd years into America's biggest communications, entertainment, and advertising medium. Is that a sin? Nor, until FM, was it a sin that (by no coincidence at all) the parameters in these interconnected elements of the AM system were of a similar degree: Uniformly lo-fi, from beginning to end and on a huge scale. The system obviously worked. The public appreciated it, obviously, and the promoters made cash. It was so successful that for most of those years there was really no change in the basic radio sound. People were used to it and they got the messages they wanted, as well as the messages which the broadcasters and ad people wanted them to get. It was big business.

And then, suddenly (it seemed), this new FM with its unassailable advantages! You could have forecast the explosion. When things came to a head, Armstrong had his 500 applications just waiting for a place in the new station roster on the "permanent" FM band, ready for a jump onto this new hi-fi radio bandwagon with technology that invalidated the entire AM network concept! What--you expect AT&T, RCA, CBS, MBS, and the like to applaud politely? Well, why didn't they license themselves for FM and simply convert, as comfortably as possible? Not likely, even for lesser commercial powers. In the face of this sort of deadly challenge, inertia is overwhelming, aided by every kind of rationalization in respect to the obvious values of present product and the highly doubtful benefits of the new. What else? ("The public doesn't want better sound" was a major argument, as it was later when our own hi-fi began to get around.) As for the large corporations, they are laws unto themselves, and most do not work in any amicable fashion at all.

GE, for its own reasons, went along with Armstrong as an FM licensee. Zenith too. Not the big fellows-and especially not RCA, where the whole network idea had originally developed through NBC. RCA apparently figured it would get along very well without Mr. Armstrong if it applied its considerable talents towards fending him off. License? Royalties? The last thing a huge establishment does is pay royalties to some lesser power! And especially not to a single inventor, entirely on his own.

That was Armstrong.

I remind you of an additional set of facts by means of which you may further guess the kind of thing that was going on and draw your own conclusions. Have you recently listened to any high-power FM stations? You are aware that many are remarkably low in power. The rationale is handsome.

Height versus power, so that each of many FM stations in an area will have the same effective clout at your home tuner. FM was for local people-right? It brought a new concept of, er, democracy in radio entertainment.

(Shades of today's cable and public access!) Very nice idea.

But the fact is that here we are, some 40 years later, quite without those big FM stations and their new network system that was so clearly "in the works" back in 1939 and 1940. Who now controls most of the large-scale broadcast networking of today, if via different means and mostly for TV? None other than the same large corporations, more or less, which owned the AM network system in 1940. Strange. And where are the big FM-only networks that Armstrong clearly had in mind and very nearly in fact? Nowhere. The later low-power FM system, if I am right, makes them quite impractical.

FM, we are often told (but not by its inventor), is for small, independent operations, for minorities (like classical music listeners!). Even our present commercial FM stations are isolated, each to its own territory. Is this really FM's true best use? It has been made true, arbitrarily. Behind the sweet, persuasive words, back in the 1940s, there was a struggle to the death. And Major Armstrong lost. Not everything, but plenty. He gave up in January of 1954. Dead of a fall from his high apartment window.

We are not so badly off, it must be said, under the present mandatory FM system, which has gone on to evolve with some logic to fit the need. But the irreversible frame, absolutely excluding Armstrong's major FM expectations, was set up in a hurry way back then, just in the nick of time to stop what FM might have been and maybe should have been--real commercial network big time.

You can imagine your own details, but Lessing lays them out splendidly in Man of High Fidelity, to make your eyes pop with astonishment. So long after, in retrospect, this story has the ring of truth. I am glad I wasn't Major Armstrong.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Aug. 1984; EDWARD TATNALL CANBY)

Also see:

= = = =