INTERNATIONAL AMBIENCE

The Roar of the Crowd

I've just had my first brief tastes of stereo-sound TV, one here and one in Japan. My impressions were fairly favorable but somewhat inconclusive.

Here in New York, the only station broadcasting in stereo seems to be WNBC-TV, but The New York Times TV page doesn't tell which programs are in stereo (Johnny Carson and Miami Vice were the only ones I caught), and my cable service (without which it's almost impossible to get a decent picture here) does not carry the stereo portion of the signal.

Faced with the choice between stereo or a clear picture, I used my window antenna just long enough to sample the stereo, then returned to the cable.

In Japan, I spent only one night in a hotel room with a stereo set, and there wasn't much stereo broadcasting (though there was a fair amount of bilingual programming) during my few viewing hours.

In both cases, stereo added more ambience than directionality to the signal. With my eyes closed, I could rarely get a feel for where voices were located. That probably will remain the case, since TV's sound engineers must bear in mind that changing camera angles can move a person around the screen at will.

Ambience, however, is nothing to sneeze at (even though it can be simulated). While I've wondered, in the past, why Japanese TV broadcasts sports events in stereo, I now know-in stereo, crowd noises really catch you up in the on-scene audience's enthusiasm! But it also makes me wonder whether the reason so little TV is broadcast stereophonically in the U.S., so far, isn't the time lag while they pre-tape enough stereo laugh tracks.

The Extinction of the AUX

The first time I saw an "AUX" input relabeled "Video," I thought it an encouraging sign that the long-heralded marriage of audio and video was beginning. The second time, I thought it a cheap way of making a component look more modern without any functional updating.

But now I see another reason for it:

A friend who has acquired his first component system just noticed that his 20-watt receiver has an "AUX" input, and called me to ask whether he should get an AUX to plug into it.

It's easy to forget, sometimes, that everybody (ourselves included) starts out ignorant. While the switch away from the old input designation may offend traditionalists, it does give explicit guidance to the newcomer.

On balance, I'd say that's an advantage. Of course, it all depends on whose AUX is being gored.

Violins and Valences

One of the reasons I am not a scientist may well be that my high school chemistry teacher spent less time discussing valences than in debating who was greater, Beethoven or Mozart. (I took the Beethoven side, but I've since switched.) On the other hand, he introduced me to hi-fi, which probably has had a greater influence on my life than chemistry ever could have. And he also told me something that has long made me suspicious of hi-fi endorsements by musicians. "My brother plays with the Pittsburgh Symphony," he told me. "You'd think he and his colleagues would have great hi-fi systems. But when you go to a violinist's house and listen to his system, all you hear are violins. At the flautist's house, you only hear the flutes. And so on." I've since met some musicians myself, and their systems actually sounded rather good. But in talking to them, I've discovered that many musicians would be just as satisfied with lesser systems. Musicians, you see, know the sounds of music so well that many can re-create that sonic splendor mentally, from even the tinny cues of a pocket AM radio. No matter what the sound system puts out, it's always hi-fi in their heads.

Even being just a music lover, as I am, can dull your critical listening faculties. Listening to music is fun; by the same token, listening past the music, to hear the system's sonic subtleties, is work. The better the music, the harder it is to ignore it and concentrate on the sound. And the better the sound, the harder it gets to ignore the music, too; there's less of a barrier to your enjoyment.

As I think I've said before, this has made unconscious musical enjoyment one of my clues to a sound system's quality. At a show, if I find myself drawn into a booth to ask what record is being played, it's a good sign that the sound was so good that I became unconscious of it. I then shake myself and pay attention to the sound for a while-preferably on music I don't much like. Which is more or less what I had in mind when I told Brian Cheney of VMPS, at one Consumer Electronics Show, "Enough music, already. Let's hear some hi-fi!"

Opinions of Difference

A few years back, when Linn first posited that turntables made a difference in recorded sound, I was skeptical. Then I attended a demonstration at which a record was played repeatedly on several high-end turntables, all equipped with the same models of Linn arms and cartridges, and I clearly heard a difference, every t me. I still retained a touch of skepticism (cartridges vary; could Linn have hand-picked the one on the Sondek?), but I was basically convinced Yet when the high-end dealers present oohed and aahed over how "major" the difference was, I disagreed. To me, a major difference is one that can be heard clearly and repeatedly, even after a lapse of time and under varying circumstances. By that criterion, the difference between the Linn and the other turntables was worthwhile, but minor. Similarly, differences between most high-quality components of the same general type (amps, for instance) are minor.

Admittedly, I'm using a rubber scale. To me, a major difference is one that I can hear under all circumstances. As I learn to hear what I thought were minor differences more clearly, they become major ones ... to me. I hear some things better than others on the Audio staff, and hear other things less clearly.

What about differences anyone can hear, without any aural education? They're not major differences-they're gross ones.

Admitting Ignorance

It's easy to assume that any hi-fi magazine editor has heard the particular audio components that interest you. Maybe we have. But it's more likely that we haven't.

Our Annual Equipment Directory listed 3,700 products in 1984. Assuming that only half of them are new in any given year, and assuming we listened to those new items 50 weeks a year, we'd have to audition 37 of them per week-roughly one for every working hour. (Though editors actually work a lot more than 37 hours per week, regardless of what the job descriptions say.) That would leave us no time to put out the magazine.

In practice, we do hear a lot of audio components-many briefly, some at length. But if you're looking for something specific and live within shopping distance of a major city, the odds are that you've heard more components fitting its description than we have.

Keeping Track of Tracks

I'm still digging out from my recent move, which means my computer is out in the living room, next to the audio system, instead of back in the bedroom that will soon become my home office. It's proving so handy where it is now that when it does go back where it belongs, my little lap top computer will be moved to the living room as an audio accessory.

I've already written about the program I devised which adds up selection times to see what tunes will and won't fit onto a given cassette. But I have other audio-related uses for the computer, too.

One use is in labeling the slots in my record cabinets. I have over 2,000 records stored in compartmented cabinets, each compartment devoted to a different type of record. Over the years, the compartment boundaries have shifted to reflect my shifting interests, but their labeling has not.

So I redid the collection after my recent move, using my computer first to list the compartments as they were, then to rewrite and update the list, and finally to print out new labels for the compartments. To turn the single spaced list into triple-spaced label sheets with dotted "cut here" lines between each, I had only to issue one command line-my computer did the rest.

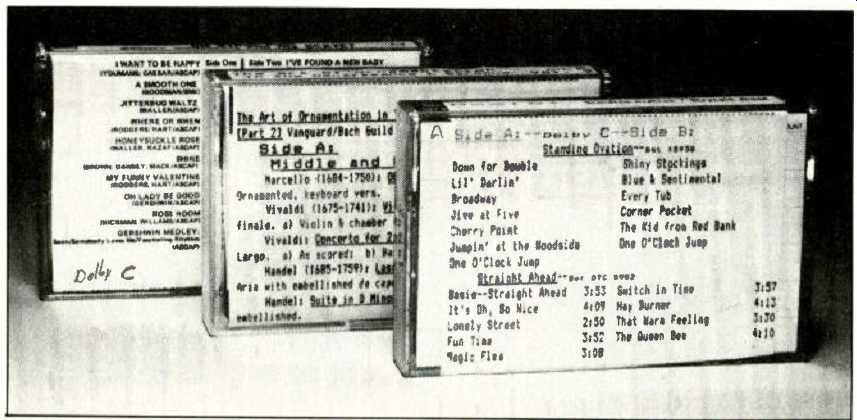

Another use is printing liners for the cassettes I dub to play in the car. My word-processing software (Powerscript plus SCRIPSIT, if anyone cares) and my Star Gemini dot-matrix printer let me print in varying sizes within one document-in this case, a cassette label. So I print the album title large, for the spine and header; print the selection titles normal size, underlined and bold, and print subsidiary information in smaller and/ or lighter type. If I find a typing error, or rearrange the selections on the album, the word processor makes it easy to redo the liner slip. I find it easier to print on regular paper and glue it to the cassette's original cardboard liner slip than to print directly on the cardboard.

It's also possible, of course, to photocopy the original disc's or tape's jacket or liner slip, and make your slip from that. Machines which can make reduced-size copies give you even more flexibility in this.

For those who want to print cassette liner slips on their word processors (or typewriters, for that matter), the following specifications should be useful: The slips are 4 inches wide, which means your maximum typing line can be 40 characters with pica type (10 characters per inch), 48 characters with elite type (12 characters per inch), and 68 characters for the condensed style (17 characters per inch) on most dot-matrix printers. In practice, you should type a little narrower; margins add legibility.

The slip itself should be either 3 3/4 or 6 1/8 inches long, with folds at 11/16, 1-3/16, and, if you choose the long style, 3 3/4 inches. That leaves room for four lines of type on the first flap (which goes over the top of the cassette), three lines on the label "spine," 15 lines on the flap which goes under the cassette, and 14 more on the optional flap which folds over the 15-line one.

Reel Helpful

My new living room is smaller than my old, eliminating some of the shelf space I formerly used for 7-inch tape reels. Time to start weeding out the collection. But if I can't weed out enough, colleague Larry Klein suggests another space-saver:

Prerecorded tapes make up about half my collection, and many (especially pop-music tapes at 3 3/4 ips) are short enough so that I can splice two together onto one large-hub reel, and three or four onto one normal-hub reel.

The Dolby-dbx One-Two

Of all common home noise-reduction systems, dbx gives the widest dynamic range. However, on some material you can hear it "breathe" a little, as the noise level in the input signal varies along with the dbx system's compression and expansion. Dolby systems don't breathe-but they don't have as much dynamic range, either.

The obvious solution, pointed out to me by Bill Cawlfield of Vector Research, is to use both at once dbx for the dynamic range, Dolby to reduce the trace of breathing. (He says Dolby B NR will do this well.) The catch is that, if you have a tape deck with both systems, it won't let you use both at once-a matter of rivalry between the NR-system companies. If you have a deck with Dolby B plus an external dbx adaptor, however, you can do it. That, says Cawlfield, is one reason why Vector put a dbx system into its receiver instead of into its matching, Dolby-equipped tape deck; the other reason was to allow decoding of dbx discs.

Arm-Twisting

Ever install a tonearm on a turntable? Fun, isn't it? The problem is that the tonearm hole must be drilled in precisely the right spot, and the cartridge installed in just the right location in the arm shell, or you get increased tracking distortion.

It's a precision job, and most tonearms come with Stone Age tools to help you with it. Most commonly, in my experience, you get a cardboard template with a hole punched to fit the turntable's spindle, and another punched where the hole should be drilled in the turntable base, often with lines drawn that show where the stylus should rest once it's in the right position.

That's all the information you need to do the job. The trouble comes when you try to use it. First, you have to rest a flat, floppy template on a turntable that usually rises about an inch above the surface you'll be drilling.

So you have to prop the template to prevent it from sagging (a sag would shorten the indicated arm/spindle distance), then poke a marker straight down through the template to mark where the arm should go. Then, if your only cartridge-position indicator is the lines on the template, you must figure a way to put the template back into position after the arm has been installed. Some templates are cut out to allow this, but others are not. If the template designer has too literally interpreted the stylus/spindle distance as "overhang," the stylus-position line may be just past the spindle, where the cartridge can't be set down because the spindle's in the way.

(Truth to tell, I only ran into that problem once, years ago, but it still rankles.) Some designers do give you more help. Over the years, I've had a few Dual turntables with plastic cartridge-

position gauges that fit over the cartridge-mounting slide (more snugly on some models than on others).

Shure's V15 Type V cartridge comes with an ultra-dandy mounting jig (usable, alas, for no other cartridges I know of); I understand AKG packs mounting aids with some of its cartridges, too.

There are also general aids for mounting and positioning cartridges, such as Mobile Fidelity's Geo-Disc and the grid on one disc of Telarc's Omnidisc. But I haven't found a great deal of help when it comes to mounting arms.

On the other hand, I haven't mounted every thing on the market (thank goodness!). And since mounting provisions are rarely discussed in ads and catalogs, I'd welcome hearing from readers about arms, cartridges and other products that make the process easier. (If a manufacturer wants to nominate his own stuff, fine, but he should send a copy of the appropriate instruction manual.)

(adapted from Audio magazine, Aug. 1985)

= = = =