FILE QUIRKS

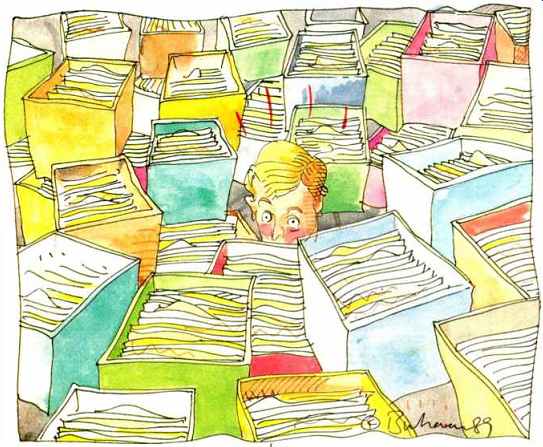

Lately, I've been cleaning house and throwing out, not wishing quite yet to join the Collier brothers. About time, after more than 42 years with this magazine! What an accumulation of stuff--that's the safest word for it. For all these years, I have kept this stuff safe and dry in my dwelling places, and now, you might say, I am awash in it. Old audio equipment, yes. But much more prominently, yard after yard of solidly stacked paper, valiantly filed and filed and filed in case of future need. What need? That's always the question, and the answers keep changing.

I ran out of big metal file cases on roller bearings years ago and turned desperately to old cardboard cartons.

Now they are everywhere--corners, desk, table tops--and not only do they bulge, but they burst, the files spewing out. It's terrible. I am a Collier brother.

Or will be soon. The inflow continues.

Throw it all out quick? Ah, the easy solution, the sort that unmakes history in every age. Junk? Who ever knows? if you have a conscience, you do not throw out quick. So with a conscience, and interest, too, I am a squirrel. I keep. On a chance.

It's like those lottery tickets with the odds printed right on them. One chance in 40 million? Go for it! I just cannot miss the chance of some value in all that stuff--or throw out the enormous effort it symbolizes, over the years, without even a look-see. Yes, 99% is indeed and indisputably leftover junk. Reams of invoices, memo sheets, bills of lading (1959), tattered instructions for nonexistent equipment, routine business notes in standard format, plugs galore: "Dear Sir or Madam, I am about to introduce you to the greatest hi-fi sound you will ever experience, brand new for 1961...." A bloated mass of triviality, long departed, and long may it rest in oblivion! Yet in the middle of all this is the other stuff, extremely well dispersed and easy to miss. The older world of audio itself, alive and strong. It's bad enough to junk all the labor I did in answering 1,000 letters, along with my slaving and highly intelligent sec'y, who typed, filed, typed, filed, year after year so neatly, until she went on to better things. Beyond our efforts, there are those other souls who return to life-if I pause a moment in sorting--almost stifled among the invoices. Every so often, one of them suddenly communicates out of the past--or so does a colorful leaflet-to persuade, to inform, to offer useful thoughts, ideas, and explanations, or just to kibitz. This is our world in the very shaping, moment by moment, back then. How can I junk it? I mean, sight unseen.

If I do not cope with this philosophical problem, a large dump truck will eventually do the job for me.

Only last year, screwing up my courage, I made a start. I opened up a lowly "Small Business" file, company by company, and pulled the dusty folders out one at a time, just to see what I could do. Mostly a batch of silly or routine products, the predecessors of the routine products of today. So the work went fast. In a long evening, I got through about 2 feet of files and saved only about 2 inches. But there were items to give me brief pause, even here. Sprightly letters from the founders, the chief engineers, the sales reps. I rescued a little bit of each of them, and it felt good! Only 24 yards of file to go. The junk slid neatly into the compactor chute of my New York City apartment building.

In my Connecticut home, things are not so simple. The cardboard boxes were, for a time, a brilliant idea--economical, space-saving, efficient. But cardboard is not for the ages, even my age. Now the spewing is relentless. If I lift a box, the bottom falls out or the sides collapse. On the floor, I stumble on one and out pour 1,000 pages, jumbled. Ants get into the cardboard tunnels; spiders weave sticky webs. Buy expensive metal cases for this stuff? Not ,before reducing the sheer mass, thank you. And by a lot.

I am no file man. My mind is much too inventive, my memory too short. I can think of a dozen heads under which every item could go-then I forget which heading I chose. To file is to lose. Thus, any recent stuff that seems important is left out, where it remains visible (until buried by more "visible" material). The persistence of time annoys me. I have folders marked "Current Letters" to keep myself up-to-date. Another file follows and another "Current." Straight in front of me, as I write, I see a folder (in a new cardboard box) marked "AUDIO Letters-Lately." How "lately," I will not tell you. Behind it is another that just says, "AUDIO." Then there is "Recent AUDIO Correspondence." Should I go on from that to "More Recent"? To be sure, I've made one improvement of great psychological significance: Instead of recycling the paperwork, I recycle the folders. When I run out of them, I just have to get to work on another cardboard box--to retrieve its folder content. This adds urgency to my task, something I deeply require.

I am assisted in the accumulation of ever more stuff by those who, obligingly and innocently, copy off and send to me all sorts of paperwork of real audio importance, industriously complete, at length, and in bulk. No complaints! Very helpful and interesting. A fine example, a couple of years back, was a whole fat set of proprietary newsletters, around 1935, from that pioneer hi-fi maker E. H. Scott not (H. H.). In those distant years, older readers will remember, Scott built an astonishing "radio phonograph," with specs that stand up remarkably to this day. Quantities of big tubes, for versatility and to build up power, AM radio with variable bandwidth so you might choose wide-range hi-fi or long-distance precision reception. No FM; it wasn't around.

Neither were solid state, integration, or digital. I was sent four or five of these well-written newsletters-publicity, but on a reasonably high level. I was so intrigued by their voice from the hi-fi past (using the term high fidelity even then) that I sent them on to Technical Editor Ivan Berger. Dutifully, he copied them and sent them back, and I filed them away--all 2 inches or so. Only I forget just where I filed them.

Two readers sent me off-copies of the original print face on an LP made by Virgil Fox playing the famed Wanamaker organ in Philadelphia. The LP, I knew, was way back, and I remembered having played it; now it had been refashioned, with some debatable tonal adjustments, on CD. My copy was not to be found (no doubt on "permanent loan"), and on it was the proper information I would have liked to have around. Thanks, then, to readers Robert Baker of Humboldt, Iowa and Lewis Millett of Kensington, Md.

Another major category of old files is not companies but subjects of some special continuing interest. Wow, are these revealing! It's always my habit to collect anything and everything I see that relates to such a category, especially if I may one day be writing about it. This includes not only company handouts but all sorts of ads, newspaper articles, pictures-anything even marginally apropos. Bulk! But I can use it. Thus, the other day, I hauled out an old "Binaural" file, about 3 inches thick and dating mostly from my first years of interest in that subject in the 1950s. True binaural-that is, recording and playback of two-channel material for 'phones, each channel going exclusively to one ear.

As to binaural recording, after 35 years I do not perceive any significant breakthrough, in spite of dummy heads, mini-mikes, JVC, Sennheiser, Bob Carver, and John Sunier. Plenty of highly technical and expensive research and large doses of wishful thinking, I say. (At last, you hear it out in front!) My 1952 binaural sounds much the same as the very latest. But on the playback scene, there was a huge and paradoxical breakthrough--the tiny Sony Walkman, with its miniature 'phones, and all the millions of its successors.

The paradox is, very simply, that the sounds we listen to on those fabulous players are almost never binaural in the mike pickup. Instead, they are stereo--two channels designed for two loudspeaker systems. Yes, we hear them in binaural, each ear with its own channel. But we love the altered stereo sound! So why bother with special binaural recordings? Anyhow, in my voluminous "Binaural" file is an astonishing collection of forgotten audio, if you can call it that--notably, the addition of the first soundtracks to 8-mm home movies. To my surprise, this was, for a time, a very big thing, a real craze. Everybody was in on it, with competing products and all the normal hype: "Now you can Thrill to the sound of your Child's Immortal Words." Fantastic--such enthusiasm! Just think, four whole minutes per expensive roll of 8-mm film, a fancy new camera with turret lenses (no zoom), an elaborate projector, and a mono soundtrack, probably not very good. That didn't stop anyone. This was the sensation of the early '50s and on, as my file easily proves. The LP was only four years old; magnetic recording, at least in public, was brand new. The pictures weren't even Super8, just the old 8-mm film on small reels, not cartridged, recorded on 16 mm twice through like today's audio cassettes. The film was then split to 8 mm in the processing, the two halves joined sequentially.

All the big names were in on it. "Now hear what your home movies have been missing," says Fairchild. "Only Fairchild takes pictures that talk." That is a revealing bit. Most of the 8-mm sound was audio applied afterwards, not simultaneous with the original filming. Added commentary, musical backgrounds, very much as we know this kind of thing today. But not really a home-movie talkie.

The double talk on this basis was clever enough. "How would you like a good sound recorder that also shows movies?"' asks Kodak. "Just take your pictures and send them to us for the Kodak Sonotrack coating. Project with the new Kodak Sound 8 projector, and into the little microphone speak your comments." Whimsical but a wee bit evasive, I'd say. You did not take sound pictures with Kodak. You did with Fairchild. Also Eumig. "Sick of Silents?" asks Eumig. "Are you a disillusioned home movie producer? Does your audience doze quietly through your greatest epic?" If so, you are supposed to wake them up with the new Eumig Model C5, the camera that takes pictures you hear as well as see. This one, you discover, uses a separate, synchronized tape recorder, the Model T5. And, of course, you had to have a sound/picture projector to match, plus an amp, a speaker, and a screen.

Another flyer plugs the Elite "Talkie" projector and a film-striping service somewhat like Kodak's. And many more of the same. Such an effort and expense to produce sound from those four-minute rolls of film! A comparison with today's camcorder is inevitable.

What immortal sounds do we record with our camcorders? Mostly, we ignore audio. Hour after hour.

The strangest device I found in this old file was a home system, 6 pounds and portable, that applied a liquid magnetic "paint" stripe to your 8-mm films, right in the living room. Dried in a minute, ready for recording and erasing. The Argus Syntronic 8-mm Soundstriper. Just pop the film into the Penn Cinesone Sound Outfit, a fancy projector with amp and speaker, and you had sound movies for $99.50. (Read, $900 today.) All this, for me, had binaural potential-if only there were two stripes and two channels. It was possible because there was the Movie Sound Eight Projector of 1952, as noted in a mag called Audio Engineering. It provided two separate channels of audio playback from 8-mm film. Binaural! That's what I thought. New worlds to conquer, right and left? They are still unconquered.

You want me to throw this file out? Not on your life. Or mine.

(by: EDWARD TATNALL CANBY; adapted from Audio magazine, Aug. 1989)

= = = =