By JOHN ALVIN PIERCE

-----

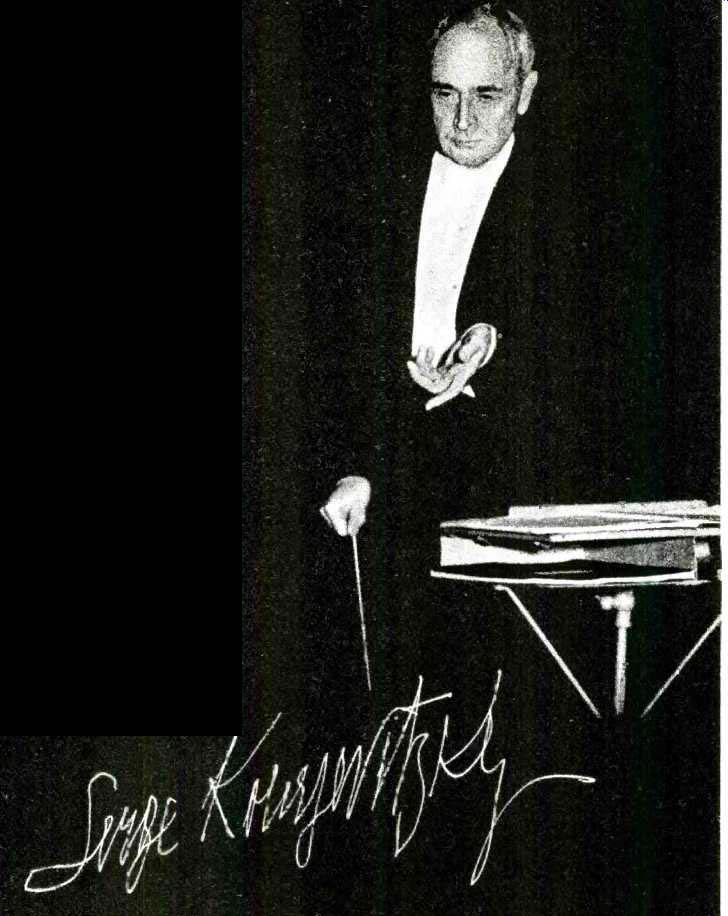

Serge Koussevitsky insisted that BSO's records be cut during actual performances. The performance was better, but harder for the engineer.

-------

In an era before I settled into my "defense" or wartime activities, I held a most interesting consulting role. This was passed on to me by Ted Hunt, who was surely already preparing for his very important work as director of the Underwater Sound Laboratory at Harvard. The Boston Symphony Orchestra had been encountering great difficulties in its efforts to avoid signing a contract with the Musicians' Union. The latest, and ultimately conclusive, difficulty was the success of the union in forbidding RCA Victor to make any more recordings of the orchestra. It could easily be predicted that, without a continuing supply of newly recorded performances, the royalties from records would soon decrease. In a last-minute effort to offset this financial threat, the orchestra trustees adopted the idea that they might well record, manufacture, and sell their own recordings.

I was introduced to this proposition by George E. Judd, a charming man who was then the manager of the BSO. Under his guidance, a man from New York who understood the manufacturing aspects was found, and I became a consultant on the recording end. Between us we selected, and the orchestra bought, all the necessary equipment. Whenever possible (and without compromising the quality of the product), the purchases were made in the secondhand market. A little room overlooking the stage in Symphony Hall was fitted with first-rate amplifiers and cutting turntables, and part of the basement was filled with electroplating tanks and presses for the actual manufacturing of records.

My primary duties in this enterprise were in the supervision of the cutting of the wax master records. Today, in the era of high-quality magnetic tape, making masters is relatively easy. The performance is recorded from as many as 16 or 24 microphones in strategic locations and on as many separate tape tracks. These, sometimes after as much as a year of study and experimentation, are blended together to produce the desired artistic results.

The same original material can then be re-mastered to meet a variety of recording needs.

In 1941 and 1942, this experimentation and flexibility were not possible. It was necessary for the original recording to satisfy all the requirements for a finished commercial release. This involved much attention to the placement of mikes and the proper mixing of their outputs in proportions that usually varied during a performance.

One policy decision, probably made by the music director and conductor, the great Serge Koussevitsky, was that the records should be cut during actual performances. Although this ensured a higher quality, as there was no doubt that the orchestra played better before a sympathetic audience than in a "cold" hall containing only microphones, it was harder for the recording engineer in several ways. It was recognized that at times the audience noise would ruin a recording, but because any important work would be presented many times, it was hoped that at least one recording would be satisfactory.

The greatest problem in making a record was the compression of the volume range of the orchestra into a compass that did not exceed the limitations of the recording medium. Should the level be too low, surface noise on a record (in the absence of either the Compact Disc or Digital Audio Tape) could overcome the signal and become intolerable; too high a level leads to distortion.

Even if the recording mechanism employed could follow the whole range of loudness possible to a symphony orchestra, the resulting music could never be played in a small room without very unpleasant results.

To avoid this, it was necessary to increase the gain of the recording amplifiers for pianissimo passages and to reduce it when the orchestra played fortissimo.

If this compression process should be carried to the extreme, so that the record played everything at a constant loudness, the music would lose much of its emotional content. This would certainly disgust a listener with any musical taste at all.

In order to maintain dynamic realism, the recording engineer needed to foresee all changes in volume. When he knew that a crescendo was coming, he inconspicuously and gradually reduced the gain so that the increase in loudness came forth with as much as possible of its full glory. Similarly, he prepared for a soft passage by bringing up the gain enough so that none of the reproduced music was lost in the background noise of an ordinary room.

Our solution to this problem, as it must be for any other engineer, was to rehearse the operation of the recording gain control as though it were another musical instrument. We learned to follow. The printed score well enough so the we could annotate it with numbered settings for the gain control. We used whatever musical taste we had to make the necessary adjustments as inaudible as possible--or perhaps should say to preserve as much as possible of the artistic values of the performance. We tried, through many rehearsals and performances, to have music students and other artists carry out, this function, almost always with discouraging results.

I’m sorry to say that the least satisfactory results were those with Arthur Fiedler, the famous conductor of the Boston Pops, at the controls. It was clear that Fiedler was too devoted to the music itself and could not simultaneously maintain necessary concentration on the recording process. The only alternative was to employ an engineer who had a modicum of musical taste but who kept the technical problem uppermost in his mind. I am sorry we did not identify a better compromise candidate than me. Consequently, I’m sure that I “rode gain” on more trials and records than anyone else. Curiously, I was never introduced to Koussevitsky In the year I spent on this effort, but I still treasure a letter from Judd in which he described the conductor’s satisfaction with some of our results.

Koussevitsky’s personal habits complicated my recording problem. He felt his orchestra could keep time, so he devoted his gestures, whether of the baton arm or the other, almost entirely to matters of inflection. It was common for the orch. to begin playing with no preliminary signal that I could see from the poor vantage point of the very small window overlooking the stage from the side. This was a great trial, because it was necessary in those days that did not permit re-recording, to start the cutting turntable soon enough so that record would have only three or four silent grooves. All too often I found the orchestra playing while I was eagerly watching for a cue. From my point of view, the performance was reduced to the status of another rehearsal.

I was sternly assured that Koussevitsky could not be troubled to give a starting signal for my benefit because, in the last seconds before beginning a composition, he was entirely occupied in mental preparations and could not be disturbed. After watching this ritual many times, I came to the conclusion that an errant cough in the last row of the audience could interrupt the conductor's concentration and considerably extend the time it took him to prepare himself. I did learn to start the recorder at nearly the right time on some occasions, but I failed much too often. I was delighted at one rehearsal when a violinist, new to the orchestra, had the temerity to inquire how the musicians were supposed to know when to begin. Koussevitsky looked at him in what seemed to be total amazement.

"Why, why," he said, "When ze baton touches ze air, you play." By the end of the year, when it was too late for the information to do me much good, one of the musicians who had become accustomed to seeing me around finally provided the answer to the question.

This was not given without an oath of secrecy, as the musicians seemed to feel that they were in deadly peril if the conductor heard of their betrayal. I was informed that when the first oboe saw Koussevitsky's baton gently descend to the level of the third button on his vest, the musician would give an inconspicuous nod which the orchestra would take for its starting time. This confession may have been akin to sending me for a left-handed monkey wrench, but it comforted me to believe that I was not alone in my trouble.

above: Roman Szulc (left) and Everett J. Firth

When introducing a new composition for rehearsal, Koussevitsky had the habit of giving the orchestra little 5- or 10-minute lectures, discussing the composer and explaining the conductor's beliefs about what the composer was trying to accomplish. These talks were invariably delightful and I tried very hard to get permission to record some of them, thinking they would be of great interest and importance to music students everywhere. I am still disappointed that Koussevitsky never agreed to this suggestion, especially because such a series of records might have gone far toward justifying the amount of time and energy, if not of money, that was spent on the recording project.

One of our great difficulties was the strength of the timpanist, Roman Szulc (pronounced, as it seemed to me, "Schultz"). He had muscles that I never saw equaled. He enjoyed baring his arm, with a drumstick between his fingers, and letting all corners feel his forearm; it felt as though it were carved out of seasoned maple. His power was a trial to us in the recording room. We would often think that we were ready for a passage rising to fortissimo when Szulc would join in with his kettledrums and send sound levels above our distortion threshold. Those of us bothered by his skill, or strength, invented all sorts of hypothetical schemes to limit his acoustical output.

Probably the most polite of these was the suggestion that we bore holes at appropriate points in the ceiling and drip water onto his drums during the performance.

After suffering from Szulc's ministrations for some time, there came a cheering day when the orchestra was rehearsing Shostakovich's Sixth. At a moment when, to me, all seemed to be going beautifully, Koussevitsky's baton went "tap, tap, tap" and the music came to a quick stop. Turning toward the timpanists' corner, extending his arms toward Szulc and then bringing his hands over his heart, the maestro, Koussevitsky, then exclaimed, "Ah, Szulc, Szulc, you play be-yooo-tiful-but too loud!" Koussevitsky's instructions to the orchestra were, to o ' one with no musical experience except as a listener, often unintelligible.

My favorite occasion was during a rehearsal of something by Beethoven, when again, the baton tapped three times. As the orchestra stopped playing, Koussevitsky extended his arms in a gesture somewhere between beckoning and beseeching and cried, "Zhentlemen, zhentlemen, I moost haff more go-o-old all over ze orchestra!" When the music resumed, I could detect no difference, but the tone must have been more golden because the conductor made no further comment.

The year in which I spent a fraction of my time in this enterprise of the Boston Symphony Orchestra was full of discovery and excitement. It had all of the fascination of any work that requires stretching one's ability and energy to the utmost. The satisfaction that should have ensued was, unfortunately, absent because the management of the BSO found it financially impossible to continue without signing a contract with the union. I never found out whether the few symphonies I had successfully recorded could have withstood commercial competition. I had, however, had a memorable experience in a world that was new to me.

(source: Audio magazine, Aug. 1990)

Also see:

The Kennedy Center (Nov. 1973)

Audiophile Recordings: Polished Antiques (Sept. 1982)

Remasters of Living Stereo (Aug. 1993)

Stereo’s Life During Wartime (WWII) (Aug. 1993)

Fast Forward at BMG (aka RCA Studios) (Apr. 1990)

============