HAUTE CUISINE

When the young William Walton was asked to compose a work for the Leeds Festival in 1931, he considered taking advantage of the large orchestral and choral resources which were to be amassed for the Berlioz "Requiem." Before he composed for these large ensembles, however, he sought the advice of conductor Sir Thomas Beecham, who said in effect, "Why not? You'll never hear the work again!" History has been far kinder to "Belshazzar's Feast" than Beecham presumed, for it may be the best-known English oratorio of the first half of the 20th century.

Since the 78-rpm era, there have always been "Belshazzars" in the record catalog. My first hearing of the work was in 1948, by way of the old recording on RCA Victor with Walton conducting the Liverpool Philharmonic and the Huddersfield Choral Society.

During the age of the LP, many more recordings were made by such conductors as Adrian Boult, William Walton (a 1959 remake), André Previn (two versions), Eugene Ormandy, Georg Solti, Maurice Abravanel, Roger Wagner (the best of the lot), Alexander Gibson, and James Loughran. So far in the CD era, six versions have been released, impressive enough, I feel, to call for critical comparison.

The work, based on biblical texts set by Sir Osbert Sitwell, chronicles the suffering of the Israelites in bondage under King Belshazzar of Babylon and the ultimate demise of Belshazzar after the mysterious handwriting on the wall appears during a great feast: Mene mene tekel upharsin (thou art weighed in the balance and. found wanting). The work is richly scored with lots of percussion, requires a large double chorus, and has a demanding baritone role. It has not always fared well in recording, essentially because too many things can go wrong either in planning or execution. Some of these problems are detailed here.

Virtuoso choral performance is required, but many recordings have been made using collegiate choruses or those consisting of too many amateur singers. What is required is an ensemble of first-rate singers who can tone down their individual characteristics and blend into a homogeneous whole. Under these conditions, a large chorus may not be needed. Another contributor to poor vocal performances is that many fine orchestral conductors simply do not know how to get the best out of a chorus.

Although the score calls for organ and two ancillary brass bands, several recordings have been made without these. Walton included extra cues in the score, enabling smaller groups to perform the work, but for recording, nothing less than the full instrumental complement should be considered.

The differences between the dramatic demands of oratorio and opera must be emphasized by the soloist.

"Belshazzar" broke new ground in the oratorio field, and few good baritones truly understand how the work should be sung. Outside the opening cantante for the voice, the role is essentially a declamatory one, providing continuity from one section to another.

The work needs to be recorded with a good sense of space and ambience

while illuminating all of the inner details. The double chorus and brass bands

provide natural stereo advantages, and the rich percussion detail must be

clear. It is a definite case for multi-miking-but without excess.

When everything comes together the right way, the work is truly stunning.

Let us see how well the current crop of CDs has made out. We'll take them in order of the recording date.

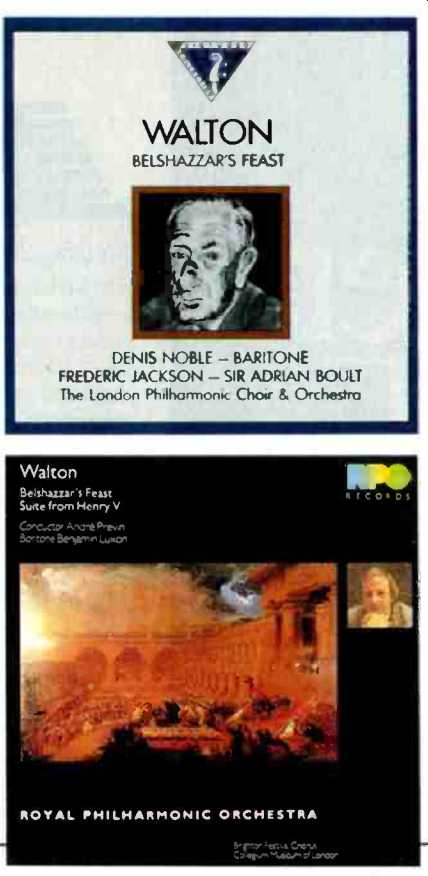

Sir Adrian Boult, London Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra. Dennis Noble, baritone. This is the only pre-stereo version of the lot. It is a reissue of the 1954 mono recording produced as a joint venture between Westminster Records and the British Nixa company and is available in two versions. One is a 1986 transfer from the original source tapes (Precision Records and Tapes PVCD 8394). The other is a 1988 transfer in which "Belshazzar" is coupled with the Walton First Symphony (NIXA NIXCD 6012) and has had stereo reverberation added to it, to the detriment of the music. As for the performance, it is an early LP landmark. The Huddersfield Choral Society is not always as precise as we take for granted in today's recordings, but the spirit is there. Both Noble and the orchestra are up to the task, and Boult's tempos are in keeping with the composer's indications. All the drama is there, but the creaky sonics often get in the way.

Despite the favorable coupling with the symphony, I cannot recommend the 1988 release of the Boult version because the added reverberation is completely out of context. The 1986 release is preferred, despite its playing time of about 35 minutes.

André Previn, London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. John Shirley Quirk, baritone. EMI CDC 7 47624 2. In the mid-'60s, Previn proved himself a superb Walton interpreter. While his zeal may have cooled in recent years, this 1972 recording shows him at his best. When the LP was originally released, it had little serious competition.

In its CD form, it is coupled with Walton's "Portsmouth Point" and "Scapino" overtures, as well as "Improvisations on an Impromptu of Benjamin Britten," and is thus a real bargain.

"Belshazzar" was recorded with Walton present, and the tempos are just what the composer ordered. Shirley Quirk's dark baritone complements the music, and the LSO Chorus is excellent. The 1972 sonics stand up well.

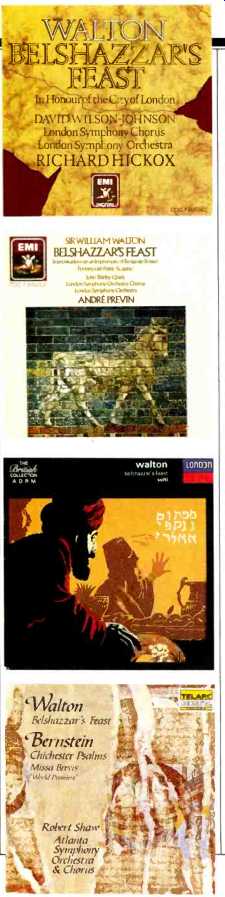

Sir Georg Solti, London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir. Benjamin Luxon, baritone. London CD 425 154-2. This 1977 recording has undergone thoughtful treatment via Decca's ADRM process, which cleans up whatever residual noise might have been in the original tapes. (By 1977, Dolby noise reduction was so well entrenched at Decca that little treatment, outside of cleaning up sticky splices, would have been needed.) As with the original LP release, "Belshazzar's Feast" is coupled with the "Coronation Te Deum" Walton wrote for the crowning of Elizabeth II in 1953. Solti's high-pressure approach to these works is often less than satisfactory. Little is held in reserve, and we get overblown chorus and brass from the onset. Luxon's splaying vibrato detracts from the declamatory role which the part calls for, and Solti allows the chorus to rise nearly a half-tone during a critical unaccompanied section at the start of the "Praise ye" section--something any competent choral conductor would never let happen. On the positive side, the recording is vintage Decca, with Kenneth Wilkinson and James Lock at the controls. Of the two works on this CD, the "Coronation Te Deum" comes off best.

André Previn, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. Benjamin Luxon, baritone; Brighton Festival Chorus and Collegium Musicum of London. MCA, MCAD6187. During 1986, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra established its own record label, and this was the initial release. I am not sure what has become of the orchestra's label activities as such, but .this item is now distributed in the United States by MCA. It was the first digital "Belshazzar," and as I noted in the pages of Audio at the time, the "see-through" quality of the new recording technology allowed us to hear far more detail in the score than we had heard before. This recording is Previn's second "Belshazzar," following his earlier one by 14 years. It shares both Luxon and the aforementioned choral pitch problem with the Solti recording; otherwise, it is excellent. It presents no additional insights which are not to be found in Previn's earlier recording, and it is coupled with the "Henry V Suite" from the Laurence Olivier film.

Richard Hickox, London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. David Wilson Johnson, baritone. EMI CDC 7 49496-2. The strong point of this 1988 recording is its superb choral work, which we would expect of Hickox. The weak point is Wilson-Johnson, whose tremulous vibrato exceeds that of Luxon. The coupling is the choral/orchestral work "In Honour of the City of London," written for the 1937 Leeds Festival and given its first recording here.

Robert Shaw, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. William Stone, baritone. Telarc CD-80181. This 1989 recording has a lot going for it. Foremost are Shaw's integration of superb choral singing with orchestral resources and baritone William Stone's intelligence and intensity. Telarc has recorded so many choral/orchestral works in the Atlanta hall that it is all down to a predictable science. Balance between the double chorus and orchestra is excellent, as is the ratio of direct to reverberant sound. I for one wish that the soloist had been slightly more forward, but this is a very small point. The inner orchestral details are superbly delineated, the organ well balanced with its subterranean pedal line, and the brass bands limned out at hard left and right. The suave Shaw choral sound may strike some as a touch too refined for the Old Testament brimstone of the work. I thought so, too, on first hearing, but subsequent listening convinces me that it is fine as it stands.

Of the "Belshazzars" available, the Boult release (without added reverberation) is an important link to the past and should not be overlooked. The 1972 Previn slightly outranks his 1986 remake, in spite of the latter's better sonics, mainly because of the superb singing of Shirley-Quirk. Telarc and Shaw walk away with the prize here, at least until EMI reissues, on CD, its mid-'60s Roger Wagner version with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and baritone John Cameron. (I don't find it surprising that the two best recordings of this complex work are at the hands of two of the best choral conductors of our time, Wagner and Shaw.) A bonus on this Telarc issue is Bernstein's "Chichester Psalms" and the first recording of his "Missa Brevis." Good listening!

(adapted from Audio magazine, Aug. 1990)

= = = =