by Edward

Tatnall Canby

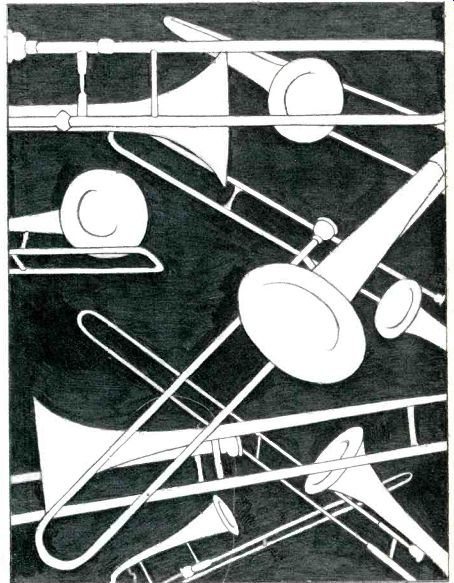

80 Trombones and 30 Basses. (Henry Brant: Orbits. Gerhard Samuel: What of My Music). Bays Bores Trombone Choir and Assisting Artists; Int. Soc. of Bassosts and percussion; Amy Snyder, voice, Nalga Lynn, soprano, dir. Samuel. CRI SD 422, stereo, $7.95.

Sometimes (quite often) I wonder why certain records are ever sent out to general record reviewers, supposedly to reach the general public. Like sending an engineering report to a literary magazine. As for CRI, there are no'doubts: In addition to supporting its professional composers and their performing artists, they're definitely out to interest and educate the general listener and, indeed, the hi-fi man too.

But what of the originators of all it!. music? Nuts on at least half of this one! Praise for the other half. Take the nuts first. A good title and in fact there are 36 double basses on side two, not 30But this piece was never intended for the likes of you and me! Specifically, it was written for the Summer School of the International Society of Bassists--hence the numbers. A solo for all.

Now this could be quite OK if the sonic results were interesting for us. But what you will hear is something else again.

The work belongs to that exaggerated school of no-rhythm sonics which originated in the first (and many sub sequent) "tape" pieces--but here the familiar zooming and sighing effects are applied to "real" instruments, which do their best to sound like tape.

Some of the results are fine--not this.

Mr. Samuel blows up a 30-second poem of Emily Dickenson into an enormous, humorless monstrosity headed off by a solo soprano who vocalizes shrieks and howls and enormous jumps, on-and-on at a snail's pace--cruelty to a mere human being. (More the fool she, for undertaking it!) These agonies are supported largely by a pitchless mumbling in the background--the mighty 36 basses. It may be stirring music for them, from inside, but out here, where I listen to the result in my living room, I found the whole thing a very conventional and, as I say, humorless lump of supposed radicalism, endlessly long and pompous for its content. Where have I heard all these sounds before? A million times over, if not for double basses. Even the strangulated soprano is familiar, only she strangles more this time. For all its big show, the work is unoriginal, a me-too piece.

Henry Brant is a much more authentic radical, and I enjoyed his 80 trombones, which sound like trombones even in the wildest sonics. Idiomatic noises. Actually, much of the music is a vast sea of churning sonic mud, huge pitch-less growls and rumbles (how do they play it?), elephantine sliding.

Maybe you'll be reminded of a herd of walruses bellowing in an Aleutian storm. A "sopranino"--a very high soprano voice (not tortured) and a brace of well-chosen percussion help the wails and the joyful yawps of the trombone choirs, all in a surround perspective (at least as of the live performance). Definitely it's alive and fun, this music, even via remote control, i.e. on a hi-fi disc. Getting together practically all the trombones in California for the event must have been a big deal in itself, almost like an AES convention.

Henry Brant once put on another surround piece (his hobby) via assorted outdoor "balconies and plaza" at Lincoln Center in New York, only to be drowned in local traffic noise plus a thunderstorm. He merely observed that NOW he understood the true sonic scale on which he should have composed. Maybe we need a Brant thunderstorm piece to replace the 1812?

Sound: A Recording: ?? Surfaces: B+

Schubert: Piano Sonata in B Flat, Op. posth. Lili Kraus. Vanguard VSD 71267, stereo, $7.98.

Superb--one of the great ladies of European pianism. Ever since I heard Ruth Geiger play this work back in the mid-'40s it has been my favorite of all Schubert; it is a towering, gentle masterpiece of expression. But very seldom is there a really moving and understanding performance, even among the pianistic great. Immensely long, it is a great sprawling thing with millions of notes, not notably difficult for professional fingers but requiring a profound musical sense--a brain piece, a drama piece on the grandest and yet simplest scale of values. Many otherwise splendid pianists are baffled by it. The notes come out, but the music isn't there.

Lili Kraus has it wonderfully well set out in her brain and emotions. The vast shape is under perfect control, set forth with casual ease from the first moments. Her fingers are no more than the able medium that gets it over to you, the listener. Perhaps there is something in this work that goes more deeply into a woman pianist's consciousness than a man's? I note with surprise that all the performances which I can remember disliking were by males. Perhaps it's a matter of negative machismo--the music is strong enough, loud enough, even fierce and stark at times, but it never shows off, it is inward and full of grace.

In the confusing Schubert chronology, this work seems to have been the very last on a large scale, a couple of months before his death. That accounts for much of its power.

Sound: B Recording: B+ Surfaces: B

Wilhelm Furtwangler Conducts Weber, Der Freischutz (1954). Grummer, Hopf, Bohme, Streich, Vienna Philharmonic, Vienna State Opera Chorus. Vox Turnabout THS 65148/50, 3 discs, mono, $14.94.

This Salzburg performance of 1954 finds Furtwangler in his latter rehabilitated days, after a somewhat unfortunate career among the Nazis during the war years. With a fine cast and the best of Viennese musicians, it is bound to be a good version, very much in fine style and full of the right kinds of feeling. But my impression is that the great conductor is nervous and a bit hasty, sometimes to the point of confusing his performers. Not really at his best, as of earlier on.

This is very, VERY much a live performance! Almost the loudest sounds in the whole thing come from the rattly floorboards of the stage in Salzburg, a bit of realism that is maybe just a bit too real. There are all sorts of rustlings and bustlings, war whoops, cries, clanks, squeaks--actually, all this is rather fun to listen to. The company is vivacious as a whole, the chorus very much on its musical toes in the peasant-like big scenes. And the solo voices are recorded at a merciful distance, blending into the orchestra and chorus as they should. Too many recent opera recordings use the all-out close-up solo technique.

This is a Singspiel, the type of popular opera in the German language that includes large amounts of German dialog. Such vigorous chatter! Even if you don't understand it, you'll be amused.

They really go to town--vast excitement (thump, thump on the floorboards), a positive plethora of dramatic projection. Just to round out the realism, there are plenty of audience coughs, hacks, gargles and chokings--it must have been a rainy day.

Don't quail at the somewhat unfortunate beginning; the very shaky soft notes of the overture, almost lost in a mass of audience noise. Was this early tape recording? It gets off to a very doubtful start but when the body of the opera is underway things seem miraculously better. Good listening.

Sound: C to C+ Recording: B Surfaces: B

American Brass Journal Revisited. Empire Brass Quintet & Friends, Frederick Fennell. Sine Qua Non SAS 2017, stereo, dbx encoded.

Wherever you may find him, Frederick Fennell and his band music will make your toes twinkle. He is the best. On this interesting disc, he "revisits" a 19th-century band--music publication, reviving a whole series of really splendid pre-Sousa marches that probably have not been heard for more than a century anywhere. His performers, the Empire Brass Quintet, plus a lot of extra players, are top-notch, too. All in all, the music rates in the almost-awesome category and surely merits our present term "classical" as well as classic.

Band-music listeners know that there is a rather large gulf in style and content between British band music and American, this last, of course, typified by the music of Sousa. In this collection of unknowns, the most interesting thing to hear is the clearly American band style, as of the 1860s and 1870s after the Civil War, and this, curiously, in spite of the fact that some of the composers are European. There is even a transcription of music by Robert Schumann. A matter of publisher's choice, I would think--by publishing his own canny preferences for this kind of music, the man who was responsible for the Brass Band journal helped to set the tone for Sousa himself, as anyone can hear.

The recording is excellent, even though the original standard stereo issue sells at list for only $4.98. Easy to hear why dbx chose this one for encoding.

Cornet Solos: Herbert L. Clarke. Sousa Band, Victor Orchestra. Crystal S450, mono, $7.98.

The big trumpet that is called a cornet was a prime solo vehicle for astounding display back as far as the late 19th century and through the great era of acoustic recording. Like the human voice (notably the tenor, as in Caruso), both the power and the overtone content of this instrument suited the acoustic limitations of the old recording system to a remarkable degree.

Clarke was the Caruso of the cornet, though his musical medium was not opera but those salon-type tidbits (with the big cadenzas at the end) which were the very height of musical fashion in simpler days.

These reissues are all from old Victor records, with the house (acoustic-style) orchestra of that label and the Sousa band--they don't tell us here whether old Sousa himself did the conducting job in person. (Probably not, I would guess. His band got around for a passel of commercial dates without benefit of the maestro.) The orchestra and band sound typically acoustic, unmistakably tubby and muffled; but the cornet comes through astonishingly well--you would think its sound purely electrical, via microphone. And what a technique! Absolutely effortless in the most incredibly complex and brilliant passages. Only trouble is the usual one how can you listen to all that sugary music, one piece after another' Like eating a half pound of maple sugar.

One amusing extra moment: Herbert L. Clarke's own voice, announcing something unintelligibly in the old-style, high-flying manner, is dubbed in at the beginning of the first item. This sets the tone nicely.

(Audio magazine)

More music articles and reviews from AUDIO magazine.

Also see:

= = = =