Despite the encroachments of the once-lowly prerecorded audio cassette, the

venerable phonograph record remains the major source of high-quality recorded

music. The LP record has proven to be a wonderfully resilient and adaptive

medium for the reproduction of music. It has withstood the challenge of prerecorded

tape and the difficulty of stereophonic sound, and even managed to accommodate

the four channels of quadraphonic sound. The record currently has less noise

due to cutting masters using Dolby noise reduction, and improved vinyl formulations

have given discs quieter surfaces. Modern cutterheads and better electronics

have meant significant increases in the fidelity of the reproduced sound. Yet

for all of its strengths, the modern LP record is still a fragile thing. It

is subject to various forms of warpage, the soft vinyl is easily scratched,

and it electrostatically attracts all kinds of dirt. In addition, it deforms

from excessive heat, is subject to "cold flow," the vinyl can be

attacked by fungi and bacteria, and well-intentioned cleaning with some fluids

can leach out vital components in the vinyl formulation, thereby increasing

noise. If one is to enjoy optimum quality of music reproduction, the LP record

demands tender loving care. Having said all this, consider that we take the

hardest substance known to man, diamond, and then grind it to a specific contour

for a minute stylus which will be interfaced with the microgrooves of a soft

vinyl phonograph record.

No matter how good the preamp, amplifier and loudspeakers may be in an audio component system, it can truly be said that high-fidelity reproduction must begin at the stylus/groove interface. Although it may not be readily apparent, there are immense forces involved in the tracking of a record groove. Some ongoing and recent research has indicated the nature and magnitude of these forces. A spherical or elliptical stylus simply placed on a record groove can exhibit static pressures on the order of 30 tons per square inch. As the record revolves at 33 1/3 rpm, dynamic pressures come into play, the stylus rises in the grooves, somewhat akin to a boat coming up "on plane," and the instantaneous pressure is still many tons per square inch. The undulations of the music signal cut into the groove walls are causing violent vertical and lateral (45/ 45 stereo groove) motion of the stylus.

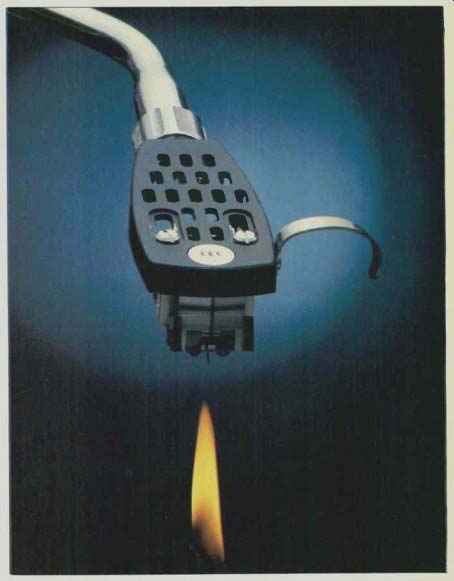

Near the inner grooves of the record, accelerations as much as 2000 G are encountered. The stylus traversing the grooves at 33 1/3 rpm produces friction, and thereby heat. Although we are talking about microseconds, instantaneous stylus tip temperatures are thought to be as much as 2000 degrees F. It is felt that through the combination of pressure and heat, certain components of the vinyl formula are physically deposited on the stylus, and some vaporization takes place which instantaneously condenses on the stylus. Vinyl formulas contain such things as plasticizers and lubricants. Lead stearate is often used as a lubricant, and it is thought likely that this is what accumulates on the stylus. Of course, much grosser materials, such as dirt, lint, various fibers, and the residues of some types of record cleaners, are also picked up by the stylus--and the result is noise and mist racking.

All of this preamble is by way of pointing out the vital importance of cleaning records and, most especially, the playback stylus. You might think that such an admonition is hardly necessary. Common sense would lead one to believe that most people do clean their records and styli. But the key point is how well do they clean, and how often? I could say there is more than meets the eye. In other words, don't depend on the naked eye to determine the status of your stylus. Use at least a magnifying glass, or better still, use a small hand-held inspection microscope. Osawa makes a handy little one, Model OS-50M, which is only 1 1/4 inches long and 9/16 inch in diameter. At a magnification of 13.6X, it gives a bit better view than the usual 10-power units. It is not really intended to detect wear facets but serves well to check the general condition of styli, especially their cleanliness. With styli which are cleaned in the usual fashion--with small brushes with or without an alcohol mixture--what this little scope can reveal still encrusted on the stylus may shock you. The worst part is that much of the dirt normal cleaning does not dislodge builds up cumulatively on the stylus. Left in this condition, the stylus will simply grind this material into the record grooves and produce noise. The better the sound system, the more apparent this noise 'becomes. Up to this point, the prudent audiophile would try to rectify such dirt problems by periodically removing the cartridge from the tonearm and laboriously try to remove the encrusted gunk. Not too easy a task since some contaminants, like the lead stearate, literally weld themselves to the stylus.

Fortunately, there is a dandy new device which most efficaciously solves the problems of dirty styli: Signet's SK-305 Electronic Stylus Cleaner. Shaped something like a Churchill cigar tapered at both ends, the device has a small circular pad of densely packed nylon bristles and a small inspection lamp on ore end. On top of the housing is a slide switch, and inside the unit is an oscillator circuit powered by a penlite battery. A small bottle of an alcohol mixture is also furnished. In use, two or three drops of the alcohol mixture are placed on the nylon bristle pad, and the stylus is lowered onto the center of the pad. Turning on the switch activates the oscillator which sets up very energetic vibrations in the pad. I am presuming that the vibrations in combination with bristles and the alcohol mixture set up a sort of scrubbing action over the surface of the stylus. The device is used for about 20 or 30 seconds and then switched off.

Since it will undoubtedly be resting on your turntable platter during the cleaning operation, it is a wise precaution to leave the turntable switched off.

Microscopic inspection of a stylus that , has been treated with this device will reveal that the stylus is absolutely pristine clean. In fact, in most cases the stylus will appear to be in brand new condition.

The alcohol mixture used in this operation appears to be of the methyl variety, and I certainly can't fault its cleaning power in conjunction with the vibrator circuit. However, remembering something I heard years ago from Paul Weathers, who you may remember pioneered low tracking pressures with his one-gram capacitance phono pickup, I checked some old notes. Sure enough, there was Paul's observation that the most efficient agent for cleaning styli is caprylic alcohol and that it is of particular use in removing lead stearate from styli. Caprylic alcohol is one of the so-called higher alcohols, somewhat more volatile than methyl or ethyl alcohol, and should be obtainable from chemical supply houses. I assure you this Signet electronic stylus cleaner works really well and is one of the best improvements you can make in an audio component system for $29.95.

I would be remiss if I did not mention here one of the older stylus cleaners available presently, the SC-2 from Discwasher. It includes a small bottle of fluid, which does a very effective cleaning job, and a dual purpose brush and magnifying mirror in a wood handle.

While the tonearm is securely locked into its rest, the stylus can be inspected with the mirror; should any contaminants be observed, the brush, moistened with the SC-2 fluid, is used to clean them away.

This little system can be most handy.

It goes without saying that a clean stylus mates best with a clean record. As you are well aware, there are a zillion record cleaning devices using some form of a proprietary liquid and various kinds of brushes and pads. A myriad of claims are made and now, like the automobile industry, rival companies dispute the merits of their competitors' products.

There are good record cleaning products on the market, and there are others which do little more than rearrange the dirt on the record. While most of us have successfully used a number of these products, there are many audiophiles who feel that any kind of cleaning fluid will leave a residue detrimental to their records. These poor souls endure the "Rice Krispies" effect, which is something beyond my understanding. Some months ago, a well-known cartridge manufacturer put me on to a record cleaning idea that I have found works quite well. You have probably seen the TV ads in which a product called Static-Guard is sprayed on a woman's dress to eliminate the static charge that made the garment cling ungracefully to her body.

My manufacturer friend said to get two large, new powder puffs, direct a short burst of the Static-Guard on one powder puff, and then rub the sprayed puff on the second powder puff. While the record to be cleaned is revolving on your turntable, preferably at 45 rpm, apply one of the puffs to the record surface with moderately firm pressure. Turn the record over, and repeat this operation with the second puff. I have found that not only does the Static-Guard clean the record very effectively, but it de-statisizes the disc as well. It also reduces stick-slip friction to a considerable degree. I have been assured by my friend that he has run extensive tests on the fluid, and there are no problems with any residue.

Although cost should not be a reason for buying a product, it is nice to known that a large can of Static-Guard costs $1 .98.

Having addressed ourselves to obtaining clean styli and clean records, another old friend of mine in the industry called my attention to a product called Gruv-Glide. This is supposed to be a sort of "spin-off" from the space program. In any case it is a very volatile liquid said to be a "dry" treatment for cleaning and de-statisizing, and most importantly, it is a highly effective agent for combating stick-slip. My friend says there are neither silicone nor Teflon-type ingredients in its formula, and the stick-slip chemical is entirely different from anything previously used for this purpose. And the stuff works like a charm. It is also applied with powder puffs supplied with the liquid.

Once on the record, you can feel the smooth slickness of the surface, and a brief buffing will remove your fingerprints.

But whether one uses these products or ones from the better known companies, such as Discwasher, 3M Co., Audio-Technica, Stanton, et al., the most important thing is to be diligent in cleaning the stylus and the record every time a disc is played. If methods such as I have described are used with good regularity, disc playback can be very significantly quieter and that, my friend, is the way to obtain maximum fidelity from a recording. It's these little things that I court.

-----------

(Adapted from: Audio magazine, Nov. 1981; Bert Whyte )

= = = =