GIVE IT A SPIN

Since the introduction of the Compact Disc, I have accumulated a fairly sizable library of good-quality CDs. I also have many digital tape recordings, an extensive collection of analog master tapes, and even a large number of four-channel masters on half-inch tape. In addition, I have a huge collection of phono graph records. I assure you that I treasure a great many of these recordings, and quite frequently play and enjoy them.

With all my superior sound sources, I continue to play my phonograph records for the most basic of reasons: The music. As I noted some months ago, classical music on CD is at this point heavily oriented to the standard repertoire and the best-selling warhorses. Even though more and more classics are being issued as CDs, it will be years before CD can hope to approach the vast diversity and broad scope of the music available on phonograph records.

Listening to CDs, one becomes quickly conditioned to their superior playback qualities. Thus, when you re turn to phonograph records, you be come acutely aware of the technical shortcomings of many of them. How ever, a number of the newer phono discs-ones whose lacquers were cut with modern Neumann and Ortofon cutting heads, then processed by advanced electroplating methods, and pressed on the best low-noise vinyl can provide remarkably high-quality sound. If the recording was made using the DMM process, sound quality can be even better.

Everyone is well aware that the quality of the playback system has a pro found effect on the reproduction of music from phonograph recordings, whether they are old or new. Many high-end audiophiles are ardent champions of the vinyl phonograph record, and they often spend an inordinately large amount of money on very elaborate phonograph playback systems.

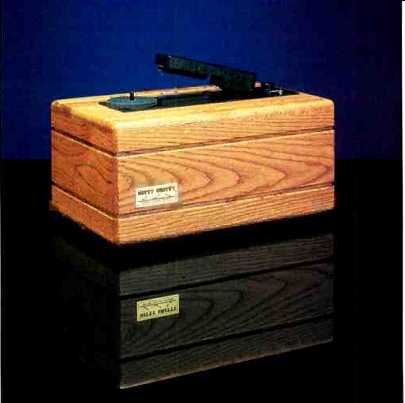

-------- Nitty Gritty Pro 2

These are the people who buy expensive, belt-driven turntables, exotic pivoted and lateral-tracking arms, and even more exotic and expensive phonograph cartridges, usually of the moving-coil variety. These audiophiles are masters in the arcane art of "tweaking" turntable systems to ex tract the last iota of performance. For instance, some of these tweakers try to find what they consider the correct vertical tracking angle for each recording they play. This is often a tedious pro cess, but once they've determined the VTA, they mark the setting on the record label so that it may be used in subsequent playings.

Some people consider it a subversion of music to technology, but the tweakers are vitally concerned with the suppression of all extraneous noises and resonances that might be super imposed on the music. These include rumble and other low-frequency vibrations, and various resonant colorations. It is enough of a problem to contend with the hiss, pop, and crack le of record-surface noises without being forced to deal with such vibratory and resonant problems as acoustic feedback, too. This can arise as structure-borne and airborne feedback, both emanating from the loudspeakers and both interacting with the stylus/groove interface.

In recent years, various spring-loaded isolation platforms for turntables have appeared on the market; they are supposed to suppress acoustic feed back as well as attenuate resonant problems. None of these platforms have been entirely satisfactory.

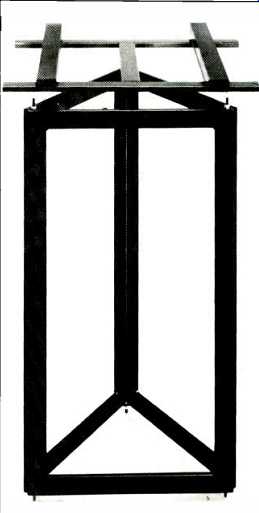

The main problem is that frequencies below 50 Hz, including subsonic frequencies, are attenuated only about 1%. A simpler and more basic problem is that most of these plat forms will not accommodate such larger turntables as the Sota Sapphire, VPI, or Technics SP-10MK2. So some tweakers have gone to such elaborate lengths as pouring concrete pillars to serve as decidedly non-resonant bases for their turntables! Recently a much more practical solution to these acoustic-feedback and resonant problems has become avail able, in the form of a dedicated turntable stand and isolation platform rather amusingly called the Lead Balloon.

This consists of a 33-inch-high, delta-shaped stand, an extremely strong, very rigid structure made of heavy angle iron. On top of this so-called Delta Tower is a steel turntable platform, 20 inches wide and 16 inches deep. On either side of the turntable platform are lead bars 1 in. H x 1 1/2 in. W x 20 in. L.

These bars have a total weight of 25 pounds, and are adjustable so that they can fit underneath the base of almost any turntable currently avail able. The bottom of the Delta Tower rests either on cushioned pods or the preferred, sharply pointed steel spikes which are intended to mass-couple the entire assembly to wooden or concrete floors for optimum performance. The turntable platform is equipped with leveling bolts.

The Lead Balloon provides a simple but elegant solution to the problems of feedback and resonance. The resonant frequency of the lead is so low less than 1 Hz-and the density of the lead is so high that it will not transmit any feedback or vibrations to the turn table. It is especially effective in the subsonic and low-frequency regions, which include such things as footfalls and compressor rumble from air conditioners. Needless to say, this also includes low-frequency elements of mu sic, such as large bass drums and pipe organ pedals, which give rise to structure-borne feedback.

I set up my Lead Balloon turntable stand with its steel spikes coupled to the concrete floor of my listening room.

In this mode, I used it with a Technics SP-10MK2 turntable (with its 37-pound lava rock/epoxy base) and the new VPI HW-19 MKII belt-driven turntable. The VPI, with its clever suspension system, was combined with Souther's latest lateral-tracking arm, equipped with the new Clearaudio moving-coil cartridge from Peter Suchy, a German designer;

I also tried the VPI with Eminent Technology's new air-bearing Tonearm Two, equipped with Shure Brothers' new Ultra 500 cartridge.

The results in both cases were exemplary. I heard just about the cleanest reproduction of phonograph records I have ever encountered. There was a singular lack of resonant coloration, and no veil of low-frequency feedback overlaid the music. Image, focus, and localization were very precise and stable. With the VPI dust cover in place during playback, and a brand-new DMM recording (which was virtually free of any steady-state or impulse surface noise), I was amazed that a vinyl record could quite honestly bear comparison with a Compact Disc.

Of course, I must note that ultimately the ravages of stylus/groove friction and contamination from dirt will inevitably produce more and more noise, while the CD will be as fresh and vital on playback 1,000 as it was on the very first play. Nonetheless, the high playback quality achieved with this combination of phonograph equipment and the Lead Balloon was quite remarkable. Even when I played the thunderous, low-frequency pedals in the direct-to-disc recording I made with Virgil Fox, the Lead Balloon did not transmit any of this very high-energy, structure-borne feedback to the turntable.

--------- Arcici Lead Balloon

The turntable platform of the Lead Balloon is available separately, sold as the Lead Belly. This is intended for use with CD players. As such, the Lead Belly can be placed on an appropriate shelf or table. It is equipped with sharpened spikes for mass coupling, but, to protect shelves and table tops, three Lincoln pennies are furnished to accept the spikes. Here, too, there are leveling bolts, and of course the plat form has the two lead bars on which the CD player is positioned.

The same company that makes the Lead Balloon also makes a clever little trestle called the Treble/Base T-1. These units can be used as speaker stands, but I found them more useful as supports for heavy amplifiers. Equipped with casters, the T-1s make such amps easy to roll around and afford quick access to the amps' in puts and speaker output terminals.

I consider my collection of phonograph records a most valuable asset because many of the musical works may not appear on CD for a very long time. Anything I can do to extend their usefulness and maximize the quality of their playback is a worthwhile endeavor. I have no doubt that the Lead Bal loon is a significant aid in achieving this optimum playback quality.

The Lead Balloon has a list price of $225. The Lead Belly is $120, and the Treble/Base sells for $20 each or two for $35. The Lead Balloon products are sold in many audio shops, or you can contact the manufacturer: Arcici Inc., 2067 Broadway, Suite 41, New York, N.Y. 10023.

While acknowledging the salutary effects of the Lead Balloon on turntable performance, some attention must be directed to certain problems inherent in phonograph records. It hardly needs saying that the main problem with phonograph records is one that has annoyed and frustrated people ever since phonograph records were in vented; this is, of course, record-surface noise. The "Rice Krispies Syndrome," as the snap, crackle and pop of impulse noise is popularly known, and the steady-state hiss as the stylus traverses the record grooves, have al ways been gross intrusions on the mu sic recorded on there is the ever-present problem of electrostatic noise.

The noise level of vinyl pressing compounds has steadily improved over the past few years. The best of today's audiophile-quality pressings are remarkably quiet. However, as most record enthusiasts are painfully aware, the buildup of dirt and grime is the mortal enemy of records and the root cause of most record-surface noises.

Microscopic examination of dirt on a record reveals that it is gritty, particulate matter that looks like rocks and boulders lying on the record grooves.

Surprisingly, even a brand-new record has a lot of dirt and debris, such as tiny cardboard shreds. The obvious solution to all this is that records must be cleaned.

Countless methods and devices for cleaning records are on the market, and most of them are highly ineffective, simply rearranging the dirt. Some years ago I reported favorably on a record-cleaning machine, and there were several others on the market which worked quite well. However, these machines were rather cumber some and a bit sloppy to use. Most of them required individual cleaning of each record side.

For some time now, I have been using the Nitty Gritty Pro 2 record-cleaning machine. To me, it is the first of these devices that works effectively and efficiently, with due regard to human engineering. Housed in a hand some oak cabinet, with a reservoir for Nitty Gritty's Pure 2 record-cleaning fluid, this machine is very simple to operate. The record is placed on a spindle, and the edge of the record engages a slotted-rim drive wheel. A record-cleaning brush and vacuum chamber contact the underside of the record. A hinged arm, also equipped with record brush and vacuum chamber, is placed over the top of the record. Depressing a rocker switch starts the record revolving. A brief touch on a pushbutton dispenses the cleaning flu id onto both sides of the record. Three or four revolutions of the record are usually sufficient, with the scrubbing action of the brush and the cleaning fluid, to thoroughly clean the record.

Depressing the rocker switch to its other position activates an extremely powerful vacuum which gives you a bone dry record within two revolutions. Examination of the record grooves with an illuminating microscope reveals that the grooves are pristine clean, no longer strewn with the "rocks and boulders" of dirt.

Older records which have had dirt ground into them and are noisy, especially in respect to ticks and pops, can be improved to a limited extent with the Nitty Gritty machine. Using the ma chine on less heavily soiled records affords lower noise levels, and using it on new recordings is quite rewarding, too. Even before the first play, running a record through the machine removes mold-release compounds and assorted debris. On really high-quality pressings, this can provide a virtually noise-free playback.

The cleaning fluid was formulated by Warren Weingrad (importer of Duntech speakers), who is a chemist and an expert in surfactants and detergents.

The fluid's chief virtue is that it leaves no significant residue on the record surfaces. It also acts as an effective anti-static agent. I have found that the use of this fluid in the Nitty Gritty Pro 2 record-cleaning machine is the closest one can come to a program of preventive maintenance in the care of vinyl phonograph records.

At $699 the Nitty Gritty machine is not inexpensive. Those who have a big investment in a large record collection will benefit the most from it. Obviously, this is a device whose cost could be shared by groups of phonograph-record enthusiasts or by members of audiophile societies. One thing is certain:

The Nitty Gritty Pro 2 record-cleaning machine is the best of its type, and provides the best possibilities for low-noise playback of records. For more information, the manufacturer can be contacted at 4650 Arrow Hwy., #F4, Montclair, Cal. 91763.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Bert Whyte)

= = = =