WROUGHT IRONY

Browsing at random through my alma mater's fancy published voice, Harvard Magazine, I stumbled third-hand on what must have been the first communications snafu by electrical transmission in all history, as well as maybe the first official public message sent over a long distance by the same. I burst out laughing and have been chuckling ever since--so typical! I'll get to that. It was an astonishingly long time ago, 145 years and some months, on May 24, 1844. In a small but important way, things were not so different then from right now.

This was, as you may guess, the inspiring telegraph message pronounced by the fingers of Samuel F. B. Morse to inaugurate a new age of communication. In his Harvard column, John Train quotes a young grad student, Edward Widmer '84 (Harvard, obviously) who dug up, shall I say, the amplified version of the famous text plus the ancillary confusion that went along with the well-known official words, "What hath God wrought?" Somewhere deep in my ancillary brain, a bell rang. I once read a very detailed account of Morse's slightly eccentric telegraphic development and, more important, the publicizing of his new invention at a place where it would count-among the influential figures of the Federal government in Washington. From which place, of course, Morse tapped out his famous question, carefully chosen ahead of time for maximum impact.

The other end of the line was in Baltimore, a lot more than a stone's throw away from the capital; so this was indeed a miracle, wrought by Morse and his teammate, God.

You'll pardon me if I amplify a bit on this Harvard story. It does have great implications for us in our several special media and numerous submedia for the transmission as well as storage of information And it's funny, too... Not Morse's humor, you can be sure. He knew better than to crack jokes in selling his telegraph to Washington.

This dignified, even professorial character (New York University) was a splendid portrait painter and general experimenter who was in communication (via pen and ink) with most of the scientific leaders of his time concerning his own and their ideas In fact, because of this, Morse was the very first man in the world to set eyes on an actual photograph-other than, perhaps, the family of his friend Daguerre.

They had exchanged accounts, in Paris, of their respective inventions, and Daguerre had given Morse a look at a stack of the new Daguerreotypes at a time when they were still top-secret. An absolutely effervescent, if sometimes rather fuzzy, thinker, Morse was also an excellent publicist in terms of his own day. (Otherwise, we probably would not have known the telegraph as an American invention-a number of Europeans were hot on the trail, too, if not with Morse's brilliant simplicity.) To launch his new invention and, of course, to raise cash for further expansion--hopefully from the government--a "do" had to be put on, with invitations to all the proper bigwigs (or, rather, tall hats) with plenty of pomp and circumstance. A show, as we might put it in public relations.

Morse had to be weighty but also terse. What to say on this first public exhibit of electrical communication at a distance? After all, speaking show-wise, there would be nothing heard at his demo but the faint clicking of his little machine, quite meaningless to all present.

And not even very convincing, when you come down to it. A few choice words then, very short but also very big, to match the dignity of all those tall funereal top hats that, I think, were already becoming the obligatory mark of every big shot from the President down to the boss of the tiniest local business enterprise.

Official language was then flowery and deadly serious, if often inspiring, as, say, the Declaration of Independence 50-plus years earlier. By 1844, what we call the Victorian age was rapidly getting underway (Victoria herself came on stage in 1837), and bright colors everywhere were converting to black-from formal dress and top hats all the way to the grand piano. This had nothing to do with the Civil War, the coming War Between the States, as you might think; it just happened. The already feeble instinct for a good joke in a public speech, which might have tempted Jefferson or Washington, was ruthlessly suppressed. No sense of humor-or so it seems today.

Morse and, presumably, his friends must have worked a long time on "What hath God wrought?" It's a top-hatted masterpiece of pompous brevity, even unto the Biblical "hath!" If God were about to pass a miracle, then this was the perfect message. So like another, more modest message less than 20 years later, when good, honest Abe Lincoln (in tall black hat) would speak quietly, in public, something inaudible about "Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth ..." (instead of the much more prosaic "87 years ago"). It is the flavor of the age.

Practically nobody could hear Abe, by the way. No mikes. Solemn, if brief. We can easily imagine the assemblage of 1844 dignitaries clustered around Morse and his machine, the insignificant wire out of it going forth in the general direction of Baltimore. The famous four words were about to be transmitted for all to see, if not to hear-unless Morse proclaimed them in a loud voice (as he surely did) while wielding the telegraph key. Somebody had to unveil them.

So here is my fanciful amplification of the conventional story that comes down to us in all its typical lack of detail. Who among us hasn't heard those words, and that they were the first words transmitted by telegraph? Inspiring thought; totally fuzzy in terms of detail! Like Washington and the cherry tree-though that, I understand, is pure myth whereas our Morse event actually did happen. Most famous stories of the sort-legends in the making, even if basically true-tend to shed all sorts of detail and nobody ever notices. Read up on the Liberty Bell; that's an interesting one. Even more, Ben Franklin and his lightning. That man was remarkably lucky not to get fried. Another man did, who was grounded. As I see it, Ben was out in the rain with his umbrella and its pointed iron tip; thus, he was well housed in reasonably good insulation to match the bumbershoot. He got the spark but was spared the funeral. Later, of course, he figured it all out and invented the lightning rod-a brilliant bit of deduction, you'll admit.

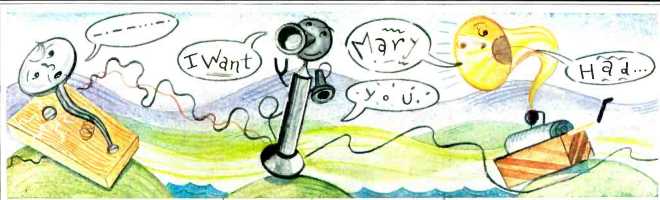

Famous first words? They became less fancy, more prosaic, as time meandered on through the late Victorian.

Mr. Bell, whose telephone went merely from one room to another, spoke that famous but flatfooted remark, "Mr. Watson, come here immediately. I want you." (If I remember it right.) As for the emperor of Brazil, when Brazil actually did have an emperor, he came to the big show, Exposition, at Philadelphia and was given a telephone to put to his ear. He, at least, had the dignity to invoke the deity, just like Samuel F. B. "My God, it talks!" he said.

In this vein, I suppose it is inevitable to bring in old Thomas Edison--actually, he was fairly young in 1877-and his famous First Words ever to be recorded-though to be sure, not electrically. He was a showman too, and when he wanted to be, also a bit of an old-fashioned humorist. His First Words were not uttered at some big publicity thing, just in his own lab, along with his familiar co-workers. So out came nothing godly at all but, instead, "Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snow...." Some comedown from those words that God had wrought for Morse only one score and 13 years before.

In my estimation, the bottom was reached when Thomas A. Edison, in his old age, was feted upon the phonograph--was it a "do" put on by Henry Ford?-and was persuaded solemnly to repeat, in a shaky voice, those same fateful words into-yes, as I remember--a battery of mikes (1927). Edison made it into the age of electronics that we know, but his interest was gone and, indeed, had departed after his only electronic discovery, the "Edison effect," which in the end led to the vacuum tube, amplification, and onwards. Edison developed a dismal ability to go into the wrong thing at the wrong time after his final really big invention, the moving picture. In his later days, he barely escaped ruin in a disastrous coal-mining venture--just as oil was coming to the fore. (Like Ford himself, who went heavily into natural rubber plantations with synthetic rubber on the horizon.) You may have heard Edison's later "Mary." It is, in a way, almost pathetic. So old and tired.

Again, audio history.

And so to the payoff. If you will return to my imagined (but mandatory) 1844 scene when Morse introduced his telegraph with "What hath God wrought?" I will complete the story. Click-click goes the telegraph instrument under Morse's hand, supposedly sending its famous message all the way to Baltimore right at that very instant, defying time, distance, even common sense.

Now, any audio person will understand, following .my reasonable reconstruction, that long before this vivid moment, there was the period of fabrication. Not the words, not the telegraph itself, but the remarkable trail of wire all the way from Washington to Baltimore. And then, the installation complete-not the formal opening! Far from it. Obviously, there would have to be what I can easily call the testing-testing period. For that breathtaking moment when Samuel F. B., minus dignitaries but probably surrounded by assorted assistants, first tried the line out at, we suppose, a preset time, with watches carefully synchronized.

Our Harvard graduate student says the man at the other end, in Baltimore, was Alfred Vail. Not having my own former source of Morse material at hand (I filed it somewhere), I am inclined to accept his info. Why not? He's out for a Ph.D. and this is a scholarly part of it. So, at a given moment in time, Mr. Vail taps out-no, not anything like "What hath God... " More likely, "Testing. Testing." If anything at all came out of Morse's instrument, 30 miles away, on that first test, I would expect it to be more like "Qrzzzfx mbzzt." Like the tests on the first transatlantic cable. (They forgot about capacitance.) You understand that Mr. Murphy's great-great-great grandfather was on hand as a matter of course. So Morse taps frantically back: "Hey, try that again. I can't read you." "Ztrsvt," says Vail. "It must be that section over the stream. Remember? Send Joe to fix it." "Psx," replies Vail from Baltimore.

Eight days later (we can guess), Mr. Morse, tired and disheveled, is back testing again. Aha! "What hath God ," he taps hastily and gets a quick answer, "Got it! You on the wire tryegin." So Morse, once more in Washington, "What hat..." and back from Vail comes, "My God, it talks. Congratsxsv." Mr. Murphy is still busy.

So, inevitably, the big day comes, all serene, and all looks well with Mr. Morse himself, but his heart is jumping.

Last-minute test. "Okay up there?" Morse sneaks in as the dignitaries begin to arrive. Right back comes, "Yes sir getting signal just fine sqgks all set to grf." Too late. The show is on. Remember, folks, those famous words made a question, more or less, and the proof that God had indeed "wrought" would be a dignified and suitable answer from the instrument, all by itself, out of Baltimore. Presumably translated into spoken words by a reputable code man. No fakery, please. So we may imagine a breathless silence as the multitude waited for the rhetorical indication as to what God had accomplished, all the way from Baltimore. For a moment, nothing. Then the machine chattered, briefly. What it said was, "Yes." Was this an answer to a previous testing question, Vail having missed the big message while, perhaps, tightening a connection or some such? The dignitaries were surely confused. Yes what? But it seems that was all there was to say. The first public communications snafu in history--electrically speaking--and thanks, Harvard, for ripping me off.

(by: EDWARD TATNALL CANBY; adapted from Audio magazine, Nov. 1989)

= = = =