JOHN EARGLE

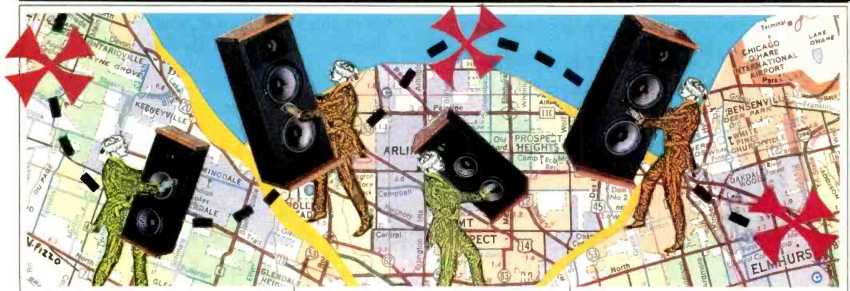

CHICAGO SHOWDOWN

Attendance at this summer's CES was down from last year, reflecting the soft economy in consumer electronics. As usual, video dominated the home entertainment side of the show, and audio was even more fragmented than in recent years.

The reputation of the Summer Show as the exposition venue for high technology may be up for reassessment, since there was very little of note in this area. Only in camcorder design were there significant steps forward in signal processing, size and weight, and useful features.

Of all the Japanese giants, Sony is the one with the persona Americans find most credible. The other major players, at least in consumer electronics, often seem faceless and without flair. Sony has been right so many times that we can easily forget its fallibility. Those of us who have been around for a while, however, will remember the Elcaset, and more recently Sony's Beta VCR format has taken a fall. The entire Sony exhibit this year was devoted to the virtues of high band 8-mm video recording. Their camcorders are remarkable, as is the array of consumer accessories intended for editing home movies. The implication here is that if Sony's Beta system is destined for obsolescence, then so is JVC's VHS system. Maybe so, inasmuch as 8 mm has the potential for better performance all around, but there is a universe of VHS recorders out there and a vast library of VHS movies that won't go away. It's a little like predicting the demise of the Philips Cassette merely because DAT is a better way of recording.

Which brings us to Sony's next big statement, actually made earlier this year, that Sony Classical (formerly CBS Masterworks) will bring out a release of 10 or so recorded DATs in an attempt to launch that medium as another format for the record industry. Since DAT machines (with a truce between hardware and software manufacturers on the copying issue) are now starting to come into the U.S., it is truly time to see if the medium can really fly on its own as a carrier of recorded sound into the home. Incidentally, DAT has already made it big in a variety of professional applications, and its position there seems secure.

The biggest problem at the CES is high-end audio. It is a minority within a minority, and the special needs of its exhibitors have not been well met in recent years by the CES and its sponsoring organization, the Electronic Industries Association (EIA). Thus, a brief review of how things have fared over the last decade appears in order.

In the late '70s, most small high-end audio exhibitors were at the Bismarck Hotel downtown, making use of normal sleeping rooms with the beds removed, á la old-style audio fairs and hi-fi shows. A few of the larger audio manufacturers, such as JBL and AR, maintained static exhibits on the main floor at McCormick Place, and simultaneously had demo rooms and/or hospitality suites in what was known then as the McCormick Inn across the street. Some of the larger high-end companies rented suites in upscale hotels where they could demonstrate their wares without interference-and not under the aegis of the CES. The Bismarck facilities were not good for demonstrating audio equipment and that activity later ended up at the Pick-Congress Hotel, below the Loop, on Michigan Avenue. The situation was a little better, but not much.

The next stop in this trek was the Conrad Hilton Hotel. That lasted awhile, and then, just a few years back, the weary travelers ended up on floors three through eight at the McCormick Hotel (the old McCormick Inn). At last, the entire show was under one roof, or at least mostly in one location, and this is something that the CES had long desired. By this time, the larger, mainline audio exhibitors had found permanent homes in the various large exhibit rooms in and around the large halls and on the mezzanine of the McCormick Hotel.

No one in high-end audio has ever been truly happy with the hotel room setup. The rooms are generally too small, and air handling is almost always insufficient-and noisy. Acoustically, the rooms are terrible. What high end audio needs is a special venue of its own with acoustically isolated spaces of appropriate size that can be acoustically treated for the particular demonstration at hand. And the costs must not be out of line, since most of the high-end manufacturers have limited show budgets. Very likely, such a venue does not exist-nor can it be hastily thrown together by the Electronic Industries Association with prefabricated booths.

Back in 1980, an organization known as the Institute of High Fidelity (IHF) put on an audio-only show in Atlanta. It was a vain effort to cater to the special needs of audio demonstrators. The show was a failure, and the IHF ended up merging with the EIA, which puts on the CES twice a year. One of the reasons for the failure was that there were, even at that time, very few audio-only dealers. By 1980, most audio dealers were already getting into video, furniture, and related accessories; they had to go to the CES to see what was happening in those fields.

Meanwhile, at the McCormick Hotel in 1990, there were very few audio exhibits on the upper floors. Apparently, the Chicago fire marshal considered the heavy attendance in recent years a fire hazard, so space was limited this year to about four exhibits per floor. A few of the exhibitors I expected to find there were in prefab booths on the lower level of the North Hall (some weren't in Chicago at all), but many of them had bolted the show altogether and gone to the Chicago Historical Museum instead! As I understand it, the exhibit at the museum had been organized in relatively short order by Dale Pitcher, president of Essence, a manufacturer of loudspeakers and amplifiers in Lincoln, Nebraska. It was apparently a great success, with 40 or so exhibitors showing 50 product lines. The location offered what many of the exhibitors were looking for: Good-sized rooms (not everybody wanted or had one), reasonable cost, and to-the-point floor traffic. Another friendly touch was the direct sale of CDs and LPs to attendees, something the CES banned about three years ago. Will there be a museum show next year? Nobody would say, but it seems apparent that if the EIA doesn't come up with a workable alternative, there certainly could be.

One of the best audio demonstrations during the entire Chicago trip was in the 800-seat auditorium at the museum. Wadia (of digital processor fame), FM Acoustics (Swiss amplifiers), Dun tech (Australian loudspeakers), and Dorian Recordings had teamed up to put on demonstrations. Normally, this sort of thing is a ticket to disaster, since it imposes local acoustics on recorded acoustics, not to mention the inability of most loudspeaker/amplifier combinations to deliver enough clean sound into a fairly large space. The amps and loudspeakers were up to the task, and the acoustics of the space were not a problem at all.

The new Duntech model, The Black Knight, is of the same general format as the earlier Duntechs: A symmetrical vertical array with woofers top and bottom and with a dome tweeter at the midpoint flanked above and below by midranges. FM Acoustics is well known in Europe and is a favorite in many recording studios. Their Model 811 power amplifier, used in these demonstrations, has been designed with enough current capability to avoid output-current limiting under signal conditions that would confound many amplifiers of similar 8-ohm power rating. Astounding in every way.

Magnepan was exhibiting in a suite at the Palmer House. They were the only exhibit around, and when they turned off their air conditioning, they had absolute quiet for demonstrating. I must say how important it is for subtleties of imaging that demonstrations be made in an absolutely quiet environment. This cannot be done to satisfaction anywhere in the main show area Magnepan's new MG 2.6 produced some of the more memorable sound at the show.

One of the major trends in high-end audio loudspeaker design is the desire to cleanly create higher sound pressure levels in order to do justice to newer musical styles. This is not easy, inasmuch as the temptation is to adopt design principles that may be at odds with one's philosophical starting point.

Take electrostatic loudspeakers, for example. Two of the most prominent manufacturers in the U.S. are Martin Logan and Acoustat. Both have devoted considerable engineering efforts to make their products handle greater input power without arc-over problems, and both have successfully integrated their upper-range electrostatic transducers with dynamic low-frequency elements (cone loudspeakers) for added acoustical output capability. This is not easy to do, because the basic radiation pattern of a cone is that of a monopole (omnidirectional), while that of the electrostatic is a dipole (bidirectional). These are the physical descriptions, but think of the difference purely in terms of the electrostatic transducer having back radiation which is 180° out of phase with the front. The matching of the two patterns is no simple task, and making the transition seamless is a matter of carefully choosing crossover slopes and placing the crossover point in a frequency range where normal room modes will tend to mask the front and back pattern differences.

Both of these companies have succeeded admirably.

A similar challenge faced both B & W and KEF some years ago. Ten years ago, these two British companies were noted for rather polite British sound: Smooth, laid back, and with great attention to imaging. In recent years, both companies have made inroads into the world of studio monitoring (mainly in Europe), where higher levels are necessary. Both have met the challenge by converting over to ported low-frequency sections for greater output, and in the case of KEF to multiple-tuned low-frequency systems. These changes are apparent in recent consumer designs, and B & W's recent Model 800 is an imposing statement in that regard. The 800 contains two 12-inch transducers in triangular enclosures, top and bottom, with a midrange/tweeter combination separating them. When I heard them, the sound was imposing, but a full assessment could only be made under better listening conditions. It seems that the original "laid back" quality, which many may have preferred, has given way to an "up front" quality for the American market-or is it that way for all markets? On another front, a handful of American electronics manufacturers have made it well into the high-end international amplifier market. Such companies as Boulder, Mark Levinson (Madrigal), Krell, and Audio Research come to mind. Most of these companies have approached digital technology with reservations, mainly because it required a different set of talents. Krell has faced the problem head-on with two companies. Krell Digital had on display a magnificent stand-alone CD turntable, along with several models of digital processors for it. Across the room, Krell Industries was showing their newest Class-A amplifier, the KSA-150, capable of doubling its continuous power output into successively halved load impedances all the way down to 1 ohm.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Nov. 1990)

= = = =