Media and Other Madnesses

From the beginning, the Consumer Electronics Show activities, sponsored by the Electronic Industries Association, have been trade events organized to keep dealers abreast of new product developments in an ever-expanding field. For many years there was only one show a year, in the summer in Chicago, and then about 20 years ago a winter show was introduced. Nobody relished going to Chicago in January, so the winter venue was soon changed to Las Vegas.

For more than 15 years the Las Vegas show has prospered. The Chicago summer show, on the other hand, has been so flat in recent years that many manufacturers have talked openly of pulling back, possibly attending only one show per year. One problem with the Chicago show is that it comes too soon after the Las Vegas show (just a little more than four and a half months apart this year), and in many areas of product development, there is little new to exhibit, just production versions of the prototypes shown in January.

A quick check of the program booklets for the two recent shows indicates that the exhibitor base in Chicago was only about two-thirds what it was in Las Vegas, with registration way down to boot. This trend has been under way for some time, and the CES management tried to bolster the flagging attendance by opening the last day and a half of the show to the public for an admission charge.

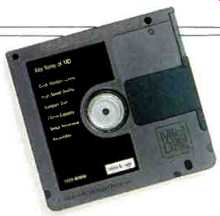

The MiniDisc's underside. Protective shutter at right slides open during play.

I don't know how successful this was in the large picture of exhibits at McCormick Place, but judging from public attendance at the high-end exhibits at the Hilton, I'd say it was not very effective. Other exhibitors, primarily suppliers to the industry, had virtually nothing to show to the public and closed their stands at noon on the third day.

Whatever problems CES has cannot be solved by opening the show to the public, and in the long run such an approach will only alienate exhibitors.

Joint trade/consumer shows are common in Europe and Japan. This works there mainly because travelling distances are short, allowing people from the relatively few major market areas to converge on one location; a single show can thus adequately serve both the trade and public.

In the United States, distances are far too great for such a plan to be successful. This points up the necessity for something that has long passed from the general scene-the "audio fair" concept. I am thinking of this in the same general context as boat shows, auto shows, camera shows, and the like, which happen yearly in metropolitan centers all over the country. But this is a subject for another time; suffice it to say that we cannot successfully piggyback an audio fair on top of a trade show.

The biggest thing in audio at CES was the unveiling of Sony's MiniDisc (MD) and its market positioning as a direct competitor to Philips' DCC. The positioning is about as direct as you can get; Sony intends for the MD to become the new standard for "audio on the go" in automobile and Walkman applications where the cassette has long been king. Of course Philips has the very same plan for DCC. Overall, both systems are equivalent in sonic terms. Both are recordable, and neither seems to have a clear advantage over the other in the cost department.

Beyond these points, their advantages diverge. The DCC provides a line of continuity with the past in that all DCC machines will play older analog cassettes. The MD players will not accommodate older CDs but will offer many of the advantages of CD, such as no wear on the medium and very rapid access time to individual program tracks.

The big question is this: Why, in these economic times, are two titans squaring off for a marketplace battle that neither may win? There certainly isn't room for both, and a pitched battle may kill both. There might be room for one or the other-if the titans worked together. (Remember that the astounding success of the CD happened largely because of cooperative efforts between Philips and Sony-the very two companies whose systems now oppose each other in the audio marketplace.)

Video continues to dominate CES, and activity here will certainly quicken as we head toward an FCC decision on HDTV in 1993. While it should be possible this year to buy wide-screen TV sets with a 16:9 ratio of width to height (about a third wider than our current 4:3 screens), there is little to play on them that takes full advantage of the wide-screen format except for movies recorded on LaserDisc in "letterbox" style. (Letterboxing enables wide-screen movies to be viewed without undue truncation of the picture's sides, but this leaves blank areas at the top and bottom of today's 4:3 screens.) I understand that some cable services will provide screen-filling programs. This may all be viewed as an interim step toward the mid-'90s, when we might expect the first true HDTV products and source material.

DCC, like MiniDisc, has album graphics on its smooth top side.

Elsewhere on the video front, Sharp exhibited their superb LCD HDTV projector, this time using a stacked pair for added brightness when delivering a 200-inch diagonal picture. JBL formally introduced its Synthesis One, which for the first time brings some of their theater loudspeaker technology into an area heretofore dominated by cones and domes. (See September "Currents".) The Snell home theater exhibit was also very well done, with an interesting program of both music and video clips and perhaps the best standard NTSC projection system at the show.

One thing that has puzzled me has been the failure of digital signal processing (DSP) to make an impact in auto stereo. The auto stereo market seems to do very well without it, perhaps because most of the examples I've heard to this point have been so poorly executed. What I am talking about here is the use of DSP to create spatial enhancement in the car, and this can take the form of reverberation programs or image enhancement of various kinds. Conceptually, all of this makes sense because the car's interior is generally perceived acoustically as dry and confining. What better way to open it up than with a modicum of tasteful spatial enhancement? The important thing here is the term tasteful. I know from firsthand experience, both at home and in the car, that the difference between a subtle spatial effect and a grossly overdone one is often no more than about 3 dB! In the exotic loudspeaker department I came across a unusual German design that resembles a high-tech space heater! It goes under the brand name mbl and is unlike anything I have ever seen. It consists of low-, mid-, and high-frequency elements, all of which are shaped like prolate spheroids (footballs) stacked vertically. The upper ends are fixed while the bottoms are driven by voice coils. The spheroids are flexible in construction, and they execute a 360° pulsating motion when driven by the voice coils. While most loudspeaker mechanisms perform best when they are kept as simple as possible, these transducers are, by their very nature, of complex construction. The large bass section is constructed of alternating pieces (a little like barrel staves) of rigid aluminum and flexible, neoprene-like material.

The aluminum pieces are further carefully damped to minimize secondary resonances. At a sensitivity of 80 dB, for 1 watt at 1 meter, the system is quite power hungry. The speakers sounded quite good, with the characteristic spaciousness of omnidirectional designs. And what is the price? About $29,000 for the pair!

There were highlights to this CES, and I have noted a few here. But I hope that organizers can work on ironing out some of the wrinkles, that they can keep CES a trade show only, and that this summer show can hold its own against its winter counterpart in Las Vegas.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Nov. 1992)

= = = =