by John C. Hallenborg and Edward J. Foster

Though Sonic Frontiers is known to day for its amps, preamps, and CD playback gear, it started in 1988 as a mail-order parts business, branched into kits in 1990, and only began selling factory-wired equipment the following year-which led the company, in 1993, to close the circle by creating The Parts Connection, again selling parts by mail. Now that division has its own Assemblage kit line, aimed at the do-it-yourselfer who has some soldering and wire-stripping skills and a couple of hours to spare.

The first Assemblage kit, the $449 DAC-1 digital processor, is positioned to compete with factory-assembled D/A machines costing much more. One appeal of kit building is the chance to save a worthwhile sum by performing some of the steps normally done at the factory; the saving over the equivalent Sonic Frontiers unit, the Trans DAC, is $150. The Parts Connection plans to add to the Assemblage line, with kits to build a tube line-stage preamplifier, a stereo amp based on the 300B triode, and an up scale D/A converter. Prices are not yet avail able for these intended products.

Getting Started

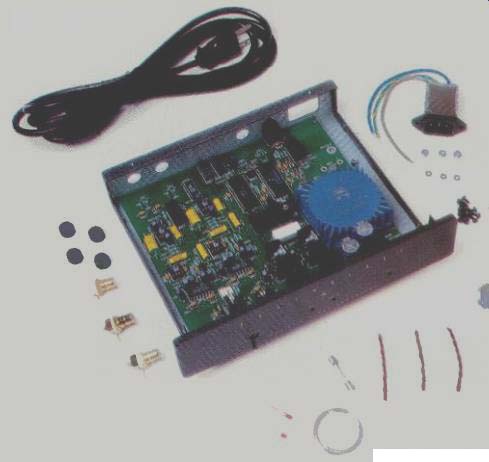

The DAC-1 kit's parts are packaged neatly so as not to put off the inexperienced kit builder. A haphazardly thrown-together bag of parts would be daunting to the bud ding hobbyist.

The accompanying kit manual presents the builder with 17 easy-to-follow construction steps. The parts are depicted in both an exploded view and in photos accompanying each step. To make this kit accessible to those who are not engineers or technicians, more than 90% of the internal assembly has been performed at the factory.

The printed circuit board is pre-loaded with ICs, resistors, capacitors, etc., lest the imprudent beginner produce a smoking amalgam of metal and chemicals. The instructions also include a primer on basic soldering and wire-stripping techniques.

Once assembled, the DAC-1 is smaller than most consumer hi-fi equipment, only 9 1/2 inches wide, 2 inches high, and 7 inches deep. It is heavy for its size, which connotes a more than adequate power supply for a device in this product and price category.

The heart of this supply, the power transformer, is of high quality, commensurate with high-end gear costing upwards of a thousand dollars.

The signal path within the DAC-1 is populated with active parts of very good quality, including a pair of Burr-Brown 20-bit 1702 DACs, a Crystal CS8412 input receiver, an NPC SM5813A digital filter, and Analog Devices' AD844 and AD847 op-amps.

The careful kit builder will have a competent, finished component that should provide many years of satisfying service. More over, should the intrepid audiophile find himself in over his head in constructing the DAC-1, the manufacturer will complete the job for the purchaser at no additional charge or, within 30 days of purchase, return the buyer's money. A completed unit, regardless of whether the owner or manufacturer finally builds it, carries a two-year warranty. There is also a toll-free hotline to call if you encounter a small snag during construction.

SPECS

Type: 20-bit, using Burr-Brown PCM 1702 DAC.

Digital Filtration: Eight-times over sampling, using NPC SM5813A.

Sampling Rates: 32, 44.1, or 48 kHz.

Frequency Response: 20 Hz to 20 kHz, ±0.5 dB.

Dimensions: 9 1/2 in. W x 2 in. H x 7 in. D (24.1 cm x 5.1 cm x 17.8 cm).

Weight: 5.3 lbs. (2.4 kg).

Price: $449.

Company Address: c/o The Parts Connection, 2790 Brighton Rd., Oakville, Ont., Canada L6H 5T4.

Construction Notes

The list of tools required to construct the DAC-1 gives a fair indication of the project's simplicity: Two Phillips screwdrivers, a pencil-tip soldering iron, a 1/2-inch wrench, a pair of needle-nosed pliers, a wire stripper, and a ruler. Everything else you need, including solder, is packed in the kit.

The initial steps in construction involve partial disassembly of the unit, as it is most practical to ship the DAC-1 partially screwed together. Next, the constructor's wire-stripping skills are tested. Great care should be taken when stripping the wires; if you must redo this often to get the desired length of clean copper, you may wind up with insufficient wire to complete the job.

As the Kimber wire that is supplied to connect the p.c. board to the output jacks has rather stiff insulation, it would be easy to cut into or snip right through the copper conductor. However, anyone with even moderate experience at this should have no trouble.

Soldering is required at the next step, when the Kimber wire is attached to the p.c. board. Thankfully, minimal skill is required. In all of the project, only a few wires are soldered, into well-marked holes in the p.c. board. Thus, there is virtually no chance for the first-time kit builder to mis locate a soldered connection.

Following more wire-stripping and the somewhat delicate insertion of leads for three LEDs, it is time to install the three RCA jacks, a straightforward alignment and nut-tightening procedure. Next looms the only point in the construction when a third hand would be welcomed: The builder must solder the stiff Kimber wire to the positive and negative terminals of the RCA jacks, which can be awkward for anyone but the nimblest technician. After that, the remaining tasks are mere screw twists and the exact positioning of the LEDs in the holes in the faceplate. Then-voila-you're done.

----------To make construction easier for the non-engineer or non-techie,

90% of the DAC-1 's internal assembly is done by to factory.

Use and Listening Tests

The Assemblage DAC-1 (which is powered up whenever its removable cord is plugged in) is certainly up to date in appearance and performance. The black, nicely cut faceplate is simply lettered and punctuated by LEDs to indicate which input is active and whether the signal from the transport is locked in.

The signals I fed to from two dedicated transports (the Audio Alchemy DDS II and California Audio Labs Delta Transport, priced at $699 and $895, respectively) and four players used as transports. The players included two up-market units (the $1,600 Denon DCD-S10 and a two-year-old Sony CDP-X707ES), an inexpensive unit (Denon's DCD-815, $330), and a portable unit (the Optimus 3400, which was recently discontinued).

I also compared the DAC-1 with the converters in the up-market Sony and Denon machines, and with an Anodyne Group the DAC-1 came FET-Adapt D/A converter, a discontinued model that originally sold for nearly four times the DAC-1's cost. After checking whether the DAC-1 could hold its own against much more expensive competition, the verdict was good news for Assemblage--and great news for the audio enthusiast on a limited budget.

Other hardware in the system included an Air Tight ATC-1 tube preamp, a QED passive control box, a pair of New York Audio Labs (NYAL) OTL-3 tube monoblocks (triode-modified by George Kaye Audio Labs), and an old transformer-coupled, 50 watt/channel Grant-Lumley push-pull design with a pair of EL34 power tubes per side. Cables in the main system were Kimber silver AG series throughout.

Loudspeakers used in the testing were predominantly Brentworth Sound Lab Type Is, a design of very high efficiency (100 dB/watt/meter). The DAC-1 was also inserted into a larger system that included Dunlavy SC-IV speakers wired to a Kaye-modified NYAL Moscode 600 hybrid amp, producing some 325 watts/channel, which in turn was partnered with a Convergent Audio SL1 Signature preamp.

Initial impressions were of a robust, yet unimposing sonic character, regardless of the partnering hardware. Once broken in and warmed up, the DAC-1 clearly resolved the most densely scored orchestral material, with only the slightest hint of audible stress.

Every other type of music that was auditioned was handled with seemingly error less aplomb.

Krystian Zimerman's fulminating passages in the Debussy piano preludes (Deutsche Grammophon 435773-2) were cleanly reproduced, with a full measure of the piano's size and more than an inkling of the instrument's tonal signature. In quizzical, introspective passages, Zimerman's superb control was easily appreciated, with no smearing. In these sections, the Sony 707/DAC-1 combination was excellent, exhibiting a solid mid-hall perspective. The Denon/Anodyne combo seemed superior only when vigorous lower octave information might tax a power supply's ability.

Then, the Anodyne's beefier supply would not be deterred, whereas the DAC-1 would intermittently render a mid-weight impression, as if Zimerman's left hand was now playing an upright piano.

Partnering either the Audio Alchemy or the CAL Delta with the DAC-1 via the coaxial connection made for a terrific match: A sense of tonal and mechanical imperturbability emerged in the Zimerman and in a starkly portrayed reading of Stravinsky's L'Histoire du soldat (Chesky CD122). This disc revealed many noncritical differences in the transports, underscoring the DAC-1's ability to reveal low-level information.

The Optimus portable and mid-market Denon machines also performed very well with the DAC-1. The Optimus fits nicely atop the DAC-1, creating a tidy but tenable playback system for audiophiles with space problems.

To the DAC-1's credit, it delineated Sigiswald Kuijken's masterful playing of his 300-year-old Granci no on the Bach Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi 77 043-2-RG) as well as the other, more expensive machines did. However, the Denon DCD-S10/Anodyne combo offered subtle, small advances in dynamic contrast and ambient detail.

Through a cutting-edge play back system, a few cuts on the Brazilian vocal stylist Ana Caram's Maracana (Chesky JD104) project an unnervingly lifelike portrayal of a woman in a state of readiness not to be further described in a family magazine. Properly replayed, the in-the-room effect can be startling, and the DAC-1 was up to the challenge, particularly with the Denon DCD-S10 feeding the signal.

With Sonny Rollins' Prestige classic Saxophone Colossus (Fantasy/Original Jazz Classics OJC-291), vintage 1956, the DAC-1 displayed none of the grainy tizziness or tonal thinness that often characterizes inexpensive CD gear. Only some of Max Roach's intricate de tail drumming seemed glossed over, prompting a wish for a mint copy of the LP.

The DAC-1 could rock 'n' roll as well, doing justice to The Pre tenders' recent compilation The Singles (Sire 25664-2). Inventive guitar chords were kept intact, and Chrissie Hynde's voice projected just the right raspy combination of skewed maternalism and taunting alienation.

In summary, the treble performance of the DAC-1 was laudable, given many CDs' limitations in this area. Midrange performance was dictated mostly by the various transports, as the DAC-1 properly passed along the qualities of the signal fed into it.

Vocal material might be criticized as being just on the dry side through the DAC-1 but the CD format has been widely criticized for just this, so perhaps the DAC-1 is merely an accurate re-player of CD sound.

During playback of CDs versus the Dunlavy/Moscode system, some minor deficiencies in the DAC-1's mid and lower bass be came apparent. Still, those whose systems deliver clean bass below 40 Hz should seek expensive gear more capable of defining the bottom octaves.

If a more rounded, harmonically enriched playback character is desired, one might seek a converter with vacuum tubes in the output stage.

Conclusion

The Assemblage DAC-1 is helping to re vive the appealing tradition of Heathkits and Dynakits of the 1960s and '70s. The DAC-1 deserves a resounding recommendation and not simply because it is inexpensive. Over a course of a few months, it was a synergistic part of costly, carefully integrated systems and did not sound out of place. Score one for the avid listener on a budget.

-J.C.H.

Measurements

Let's face it. Despite their claims to the contrary, precious few manufacturers design their own digital-to-analog converters.

Sure, they design the circuitry surrounding the converter, but most DACs and the digital filters that accompany them are third party ICs that are available to anyone. Even hardware manufacturers that own IC foundries gladly sell chips to competitors to get production up and cost down.

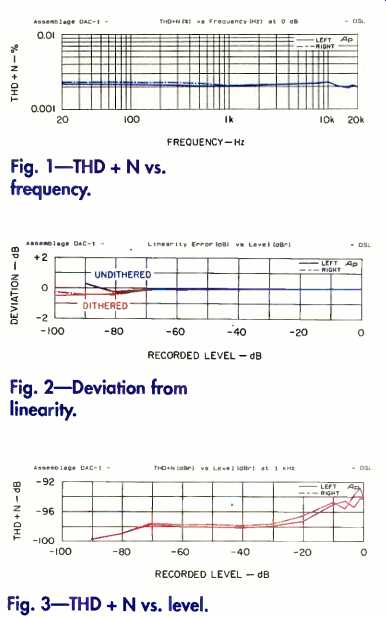

Fig. 1--THD + N vs. frequency.

Fig. 2--Deviation from linearity.

Fig. 3--THD + N vs. level.

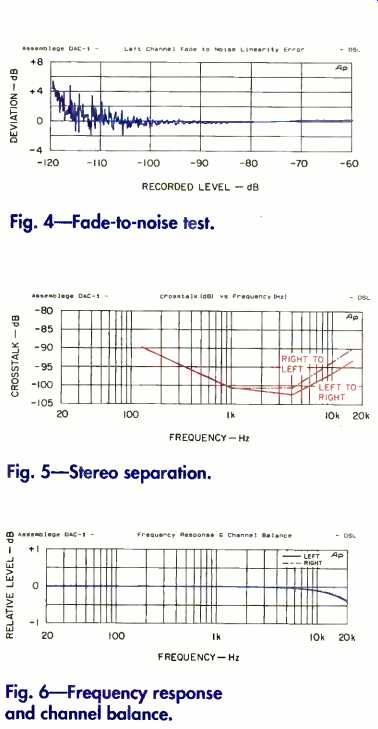

Fig. 4--Fade-to-noise test.

Fig. 5--Stereo separation.

Fig. 6--Frequency response and channel balance.

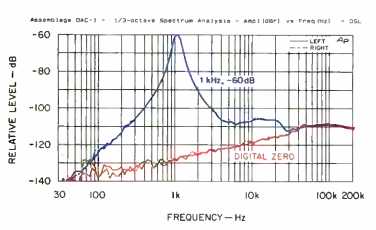

Fig. 7--Third-octave noise vs. frequency for 1-kHz signal at-60 dBfs and for

signal at digital zero.

==============

MEASURED DATA

Frequency Response: 20 Hz to 20 kHz, +0.00, -0.39 dB.

THD + N at 0 dB: Less than 0.0023%, from 20 Hz to 20 kHz.

THD + N at 1 kHz: From 0 to -90 dBfs, less than -92.6 dB; from -30 to -90 dBfs, less than -97.5 dB.

A-Weighted S/N at Infinity Zero, re: 0 dBfs: 110.0 dB.

Dynamic Range: A-weighted, 98.8 dB; unweighted, 97.1 dB.

Quantization Noise, re: 0 dBfs: -95.8 dB.

Channel Balance: ±0.00 dB.

Channel Separation, 125 Hz to 16 kHz: Greater than 89.8 dB.

Line Output Characteristics: Level, 1.96 V; impedance, 78 ohms.

==============

This being the case, why aren't all DACs "state of the art"? Cost is one obvious reason: Not every company will spring for an expensive chip, especially not for products designed to meet a low target price. Carelessness is another reason: The best DAC will not perform optimally with shoddy support. The entire system (including analog circuitry, power supply, and component layout) must work in concert to permit the DAC to attain its potential.

The Assemblage DAC-1, however, is done right. Judged in its entirety, it comes as close to technical perfection as I can recall. Just take a look at the curves of THD + N versus frequency, in Fig. 1. Outstanding! They come as near to the theoretical limits of the CD as I've seen, and do so across the entire frequency range, with none of the typical rise in THD at' and above 10 kHz. (More about this later.) Now look at the plots of linearity error, in Fig. 2. Incredible! There's well under 0.1 dB of error at the -70 dB recording level (-70 dBfs) and only 0.33 dB at -90 dBfs. And that's without dither to help. With a dithered recording, the error barely tops 0.5 dB at -100 dBfs. If there's ambience on a CD, the Assemblage DAC-1 will dig it out.

The THD + N versus level curves of Fig. 3 and fade-to-noise graph of Fig. 4 relate the same tale of perfection. Rarely do you find a DAC whose worst-case THD + N tops out at -92.6 dB at high recording levels and remains be low -97.5 dB from -30 dBfs down, as Fig. 3 indicates. In Fig. 4, I've shown the left-channel fade because it seemed ever so slightly worse than the curve taken on the right channel. Technically, however, the two were identical "within the limits of experimental error," and had I run the plots again, the outcome might well have been reversed.

As you would expect from the graph of THD + N versus level (Fig. 3), the DAC-l's dynamic range (not shown) was excellent, approaching 100 dB, A-weighted; even un weighted, it was better than 97 dB, worst case. Thanks to its 20-bit DACs and exceedingly quiet analog electronics, the DAC-1's A-weighted S/N ratio (measured with a "digital-zero" recording) topped 110 dB. But even when the converter was exercised (the "quantization noise" measurement), total noise was almost 96 dB down, which is outstanding.

Figure 5 shows interchannel crosstalk.

While I've gotten slightly better numbers on a few systems-precious few, I hasten to add-I have no grief with these whatsoever.

When worst-case channel separation approaches 90 dB, we're really splitting hairs.

It's far greater than necessary, and I've seen "dual-mono" amps do much worse! I've held the frequency response data (Fig. 6) until nearly last because I want to discuss these curves together with the spectrum analyses of Fig. 7. Over most of the audio spectrum, response is ruler flat; it's down less than 0.1 dB at 10 kHz. At 20 kHz, response is down a tad less than 0.4 dB.

Most likely, this is caused by the analog reconstruction filter. I'm sure that the DAC-1's designers could have used a less aggressive filter and/or one with a slightly higher cutoff frequency to improve the response at 20 kHz. (Not that it's bad; I'm simply splitting hairs to make a point.) However, had they done so, I'm convinced that the noise and high-frequency distortion would have been worse.

Despite the standard nomenclature ("total harmonic distortion + noise versus frequency"), the high-frequency "distortion" shown in Fig. 1 is not "harmonic" distortion at all, since a 22-kHz low-pass filter is used in the analyzer when making the measurement, which suppresses harmonics of any signal above 11 kHz. The distortion is really a form of IM caused by harmonics of the signal beating with whatever residual sampling-rate carrier is present. These "beats," when present, fall well within the audible range and are much more distressing than a loss of 0.4 dB in 20-kHz response. In short, I heartily approve of the approach taken in designing the DAC-1.

Now, if you carefully examine the spectrum analyses (Fig. 7), you'll find hardly any 44.1-kHz sampling-rate component even in the 1-kHz, -60 dBfs plot. And there are no components at harmonics of the sampling rate. Both conditions are unusual, and I believe both contribute to achieving superior sound quality. Note, too, the absence of power-line-related components and the smooth roll-off in low-frequency noise. These characteristics testify to good circuit design, careful circuit layout, and a selection of active analog components that have negligible "popcorn" noise. Care seems to be the hallmark of the Assemblage DAC-1. The channels are perfectly balanced, the output level is "standard," and the output impedance is exceedingly low.

Since the digital-to-analog converters in many of today's CD players are really fairly good, a stand-alone DAC must be out standing to justify its existence. Clearly, the Assemblage DAC-1 is. What a delight! And what a bargain!

-E.J.F.

(Audio magazine, Nov. 1995)

Also see:

Museatex Bidat D/A Converter (Equip. Profile, Nov. 1995)

Philips DAC960 D/A converter (Jun. 1988)

= = = =