By Edward Tatnall Canby

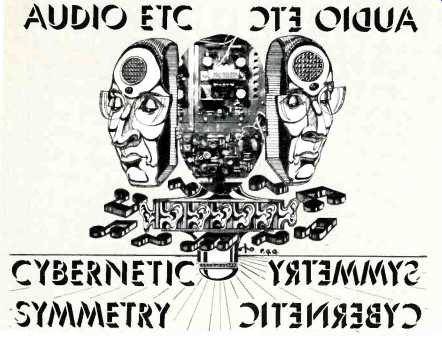

CYBERNETIC SMMETRY

Cybernetics is the prime unsung problem in consumer hi fi as we multiply our channels and our controls, hardware, cables, and, above all, our choices for possible action. I am in the midst of some very cybernetic four-channel taping right now, and I've got so much to groan about that I'm taking time off in order to toss out some helpful suggestions.

Consumer organizations have been busy for years pointing out that if your automobile's headlight switch looks and feels the same as your wiper switch, then when it starts to rain one of these nights you'll switch the lights out. Some cars make it possible for you to douse the light when you reach for the horn-a disastrous idea. The possible combinations of disasters-in the-making are indeed awesome. The solution is in controls that look, and feel, and act the way they are, in knobs that are where they ought to be and not where some other knob is.

Same in hi fi. Perhaps our audio gear is less dramatic in action when the wrong thing is pushed or the wrong knob turned. But damage can and often .does result. Much more often--no damage, but a lot of sheer annoyance, leading to high blood pressure.

It must be admitted that manufacturers design their equipment not merely to satisfy ME (or you), but to fit into all possible worlds and suit every hi fi temperament. That is a tall order. You can't do everything right and be fail-safe too. Moreover, internal requirements are hideously complicated, and a plus on the outside controls often brings along a minus with it. More often than not, I suggest cynically. Oh, for mono. Manufacturers do try to foresee problems, each according to his lights. They all work hard; they don't all succeed. But mostly they have fixed things so that the more obvious mistakes, like plugging a microphone into a speaker power output, can be avoided by anyone with half a brain.

Yet with all our new complexities, things like that do go wrong. The other day, I did it myself. I plugged a speaker power output into a mic input.

It wasn't the mouse that died, it was the elephant. I now have half a stereo amplifier as a result. The mic input is doing fine, thanks.

Note that four channels increase our options (to put it positively) by a geometrical, not an arithmetical factor-sixteen times as many possibilities, give or take a few. Do you remember the hideous complexities when stereo first arrived? Those complications are now cybernetically under beautiful control and few of us really get tangled up in our standard stereo. We have ganged switches and volume controls, paired cables with plugs attached, nicely marked inputs, neatly laid out for the eye, and so on. It's all quite easy once you get the idea. But now--we begin all over. Believe me, the four-channel hi-fi makers are sweating out there, behind the scenes.

It's bad. What unforeseen combination of buttons did we forget, the one that tore up a whole tape in two seconds? Did we accidentally wire the front right mic preamp into the rear left phono? And how come when I push TAPE IN and TUNER simultaneously there is that smoke coming up? It's a nightmare for all, and if an item gets to the store and works, without fail or confusion, the miracle really has happened. But though they test and test, the designers are only human.

So take the following observations on equipment as merely typical and not exclusive. You'll find similar problems of the petty sort in lots of other equipment. I am not picking out horrid examples. Just typical ones. Maybe the manufacturers who read here will profit a bit in their next production runs, and the rest of us will get a laugh out of it. Nice equipment, too.

The most obvious reason for confusion in controls and connection layouts, alas, is neither electrical nor mechanical. It can only be described as Art. Manufacturers have an overriding urge to produce slickly gorgeous machinery, even if it costs them money. Granted, this ties in with sales appeal; the customer tends to agree. It's not merely expensive knobbery, switchery, chromery, fancy lettering, and brushed panelings but, above all, symmetry and pattern.

Shapes, lines, colors, neatly laid out for the harmonious eye. That's the trouble. It looks fine, and who wants an ugly row of controls, each a different shape? But that's just what we need, or equivalent.

The finest example I can think of is in my home right now. Read all about the Crown IC-150 control unit and its companion D-150 power amp in our Equipment Report (AUDIO, January 1972). An astonishing pair of units.

Distortion so low that our equipment couldn't measure it, etc. Quite a story, and I was delighted when these units in due course came my way, to be put to instant use as my main audio center.

You won't even look at the power amp, which is basic and out of sight.

(It has a box, which I didn't get.) I have only one little complaint of a typically petty sort--the d--thing uses phone plugs for inputs. You have no idea what a blarsted nuisance that can be for one who changes things around frequently. You should see the jerrybuilt, patched-up cables I've invented (and lost at crucial moments) in order to cope with those presently nonstandard inputs! Well, rumor says Crown has added more prosaic standard inputs in later production. See? Cybernetic feedback.

As for the control unit, the IC-150, it is beyond this world, a super splendid doubled unit with two of everything that you'd expect only one of: two phono inputs (and mag pre amps), two tape-outs, two tape-ins, two audio outputs, etc. Reminds me of a city railroad station with fifty tracks all narrowing down to an ultimate pair. This machine is two-channel, if you can call it that. To accommodate all those alternatives, Crown has gone out of its way. On the rear you'll find a big sunken plug board with a thousand or so RCA sockets, oddly set onto a horizontal shelf built inward underneath. At the inside edge, vertically, is a panel with instructions as to what is what. Unbelievable! I haven't yet figured out what is right and what is left; I just go by plug and hunch-you really can't tell, since a front-rear pair of sockets is pictured on the panel as top-bottom. When the board is filled up with plugs-my usual situation-the instructions are invisible in any case, behind all the cable spaghetti. Even without spaghetti (a different sort this month) I have to do as I always do, shove a VW mirror down in back, aim a flashlight at it, and try to read backwards and upside down.

I'm really learning that trick, thanks to many obliging manufacturers who require the same of me.

Look, fellas, what if my equipment is up against the wall? You assume that I can walk around back and read your rear instructions right-side-up. My wall is too thick. My equipment is all hooked up. So I use a mirror and read backwards. If I can read at all.

Gotta get the light just right... . (Ha! I note that when I lean over the top of my new four-channel TEAC recorder I can look down on the inputs and find them in the same plane and relationship as the front controls, my head still facing the same way. Just reach over, and plug. Somebody, finally, is on the right track.) On the Crown rear panel it is virtually impossible, too, to plug in (or pull out) a back cable when the front one is in place. Can't get your fingers in. You have to pull out the front one-and then you lose track of which pair of holes you're dealing with; so out with the flashlight and the mirror all over again. Not very cybernetic, and I cannot allow myself to sympathize with the Crown engineers who had to get that horrendous number of connections underneath the rows of sockets. That's their problem. Ha ha.

How about an optional decal or card, for viewing all inputs from the front position?? That could help a lot.

Peanut problems, these. The visible glory of the IC-150 is the gorgeous front panel, resplendent in chrome and brushed aluminum, with the four big, silky knobs and the dual tone controls.

Those knobs! A semantic headache. I have very nearly wrecked my system time and again, through mis-aimed adjustments. Wrong knob; wrong position. They are all identical. But not their functions nor their working positions. A typical cybernetic stew, if you ask me, though I do love 'em, both as to looks, not to mention performance.

Knob One, to the left, is SELECTOR, seven positions. No problem. Knob Two, visually identical, is VOLUME and, mind you, a lot of wattage is thereby smoothly controlled. Normal volume is around ten o'clock. At noon I'm blasted. Beyond that--mayhem. So one does not turn this knob beyond the top position. But the next identical knob, Knob Three, is BALANCE-and the normal position is up, at noon. To get right channel, you turn it all the way clockwise, and vice versa. Fine-except that I grab VOLUME half the time.

Disastrous! There's worse. Knob Four, identical again, is called PANorama.

Now, its normal position is turned far left, counterclockwise, which gives you normal stereo. At noon, you get mono.

Far right and you have reverse stereo.

Phew! Three knobs, each with a different "normal" position, and all look alike. Turn the wrong one the wrong way and you have either disaster or sonic chaos. I have it much of the time. I just can't learn. You have to think each time-and you shouldn't.

That's what I mean.

This IC-150, nevertheless, is the finest and most versatile control unit I have ever used (coming after the ancient Fisher 400 CX, only recently retired-the one with the colored lights that really worked). I owe the IC-150 a debt of gratitude. For the first time I can hook all my equipment together at once, a marvelous convenience. I find many semi-pro operations possible with it that I have never before been able to pull off, including a first-class equalization of old tapes and discs via the smooth and distortionless tone controls (and the second main audio input and output). I have rescued some of my earliest broadcast tapes by this means, recopying them to sound better than they ever did before. A fine machine, if a bit whacky in its externals; so thanks muchly, Crown, and better cybernetics next time.

Then, in four-channel, there's the handy little add-on Lafayette LA-524 with SQ decoding (and "composer"), which includes a stereo power amp for your rear speakers, but uses your present amp for the front pair. A lopsided configuration, to meet a present need, and it invites some confusion--but I've been using the thing for some months with great success. It connects so that you can run all four channels via its volume control or balance front and rear or individual channels.

Alas, it is now out of service. Ahem, er, etc. I made a little semantic mistake. I misread a visible symmetry.

Now there's only one channel. My fault for being stupid, but not entirely my fault.

The problem was that I misread the layout. It was more lopsided than I thought. Two pairs of RCA output sockets, one at each end of the rear panel. (But, I'll admit, not quite symmetrically placed-probably on purpose.) One pair was to feed the power amp for the front speakers.

Regular "line" level. The other pair fed "remote speakers," rear channels.

But at what level? A switch on front turned off the rear speakers and diverted the signal to those rear outlets.

Well, what I needed was a feed from the four channels which I could mix with voice signals-music and voice in each of the four inputs to the recorder. The TEAC has a mic and "line" mix for each channel and I had nothing else on hand-so I figured I'd use the mic inputs, feeding very low.

It worked fine on the front two channels. At Lafayette's lowest volume, the front outputs didn't overload the mic input and only a bit of hum resulted.

Now, the other two channels? Well, thought I, maybe the other two outputs are also at "line" level. (Amateur line, that is, home-style.) Suppose you wanted to bypass the Lafayette built-in rear amps? There ought to be a pair of outputs for that, to match the front ones. And symmetry of position (more or less) indicated that just maybe, that designation "Remote speakers" in fact meant "output of remote amplifier for rear speakers." Four RCA plug outputs, one for each channel. Yes? Well, I was wrong, as I found out when the power signal that I actually had from those rear "remote" RCA sockets accidentally touched ground as I tried the mic recorder input. Pssst, and that was that. Power transistor.

Funny thing is, it worked, until then.

The speaker output did drive the mic input, usably, for an emergency operation with nothing else on hand.

Sure, the moral is: read the instructions. There weren't any. This was an early production model. I figured everything else out OK, but I didn't take into account the basic lopsidedness of the unit-I fell for a false symmetry. (When you get yours, there'll be instructions.) The incident, and the Crown panel configuration, serve to illustrate the unsuspected dangers of misleading design symmetry for the eye-or a symmetry, when that is misleading.

Plugs, sockets, knobs, all have instant meaning. They carry a very real message; they should always give the right message, at a glance and without ambiguity.

If our hi-fi engineers would think of their visible controls and connections as in themselves a form of direct communication, as precise as words and a lot faster, we would have fewer mistakes and confusions of the outward sort I am now describing. Knobs speak. Front panels talk loud. Rear panels shout. If the electrical connections inside your equipment must be precisely right, then the visual connections between equipment and the eye (and by feel-equally important) must be just as clearly defined. Functional symmetry for the eye must reflect exactly the same symmetry in actual operation-and the same for unsymmetrical layouts. If two operational functions are really different, then they should be different in looks, in placement, in feel. Not easy in the designing. But then, what is? There are endless ways in which the basic cybernetic aim can be accomplished. Location is important. You will never confuse two identical controls at opposite ends of a panel--unless their normal settings are confusing. Remember when we finally standardized tone controls, normal or flat position straight up, boost right, attenuate left, and the bass tone (like the piano) on the left of the treble? Before that, tone controls were dismally confusing. Position is first, but color is good, too. Shape counts heavily. Avoid those rows of identical knobs! Surface texture is very useful. Action counts. Clumping of related controls is an obvious necessity. (But be careful!) Above all, use symmetry only when it is meaningful, and the same with asymmetry. For motions, be natural. Remember the Shure pickup arm where you pushed a button down to lift the head up? The arm was vertically rigid. Nice, but wholly against nature, and of course, opposite to all other arms. Nobody could ever learn to use it right. I tried, then gave up and lifted the little head up off the record with my own fingers. Don't make 'em push a left button to activate a right speaker either. That's like a steering wheel that turns the wrong way. Nobody does things like that? Oh no? On my TEAC, in order to go fast forward you must (a) move a lever towards the left and then (b) push a button on the right. I muff it every time. No matter that TEAC has excellent reasons for having that lever right there. Very useful in other respects! But deadly for fast-forward.

No wonder designers have headaches. It's an unsymmetrical world.

(Audio magazine, Dec. 1972; Edward Tatnall Canby)

= = = =