By Oliver Berliner

The year 1977 marks the 100th anniversary of the record business ... actually not of the records as we know today, but rather the start of recording for profit, via Thomas Edison's December, 1877, demonstration of his cylinder phonograph. However, a decade later another invention emerged that revolutionized (pun in tended) the recording industry. This was my grandfather's--Emile Berliner--invention of the disc record and player, which he called the gramophone, meaning, more or less, sound of words. Alas, my grandfather's terminology is not used in France and the Americas, thus today we call gramophones "phonographs," continuing the misconception that Edison had created the disc when in reality his device was the cylinder which, with the advent of the disc record, was relegated to service as an office dictation machine and was used as such through WW II.

I once shocked a lecture audience by hinting that Edison was of Mexican descent. But consider his middle name, Alva--a very Spanish word. Think, too, that in so very many stories about Edison, his mother and his devotion to her figure prominently. So consider the possibility that the inventor's name was Tomas Alva, and that in historical Spanish tradition he adopted his mother's maiden name as his surname, while Anglicizing his Christian name, resulting in Thomas Alva E. in true Spanish culture and Thomas A. Edison for use in the United States. Think too, how little we know about Tom's father.

Why? Imagine how our Latin neighbors would rejoice if they could establish a Spanish heritage for the wizard of Menlo Park.

The Centennial, then, is surely the time to disclose some anecdotes and information about the record industry of today and of yore. Let us begin at the beginning, with the bark that started a revolution, "His Master's Voice." The world's most famous dog is not Pluto or Lassie-they're not known in nearly as many countries as "Nipper"-but actually lived and was not the figment of some adman's fertile imagination, as many have thought. He was a mischievous terrier with a considerable amount of bulldog in him, accounting for his broad chest and extraordinary strength. Mark Barraud, a French Huegenot living in England, had acquired the pup when the little nipper, as the British affectionately call their youngsters, was but a few days old. But Mark's children promptly named him Nipper because he was always nipping at their heels.

Despite the fact that he was brought home for the kids, Nipper preferred the company of Mark, a theatrical scenic designer who, when called on stage to take a bow, would often find Nipper there sharing the applause, and the noble mutt became somewhat of a local celebrity. Upon Mark's untimely death, Nipper stayed not with the children but went to live with Mark's brother, Francis, an artist of some skill but little renown even though some of his works had hung in the Royal Gallery.

While Emile Berliner or later Eldridge Johnson have often been credited as being Nipper's "master," the dog's true masters were the Barraud brothers, neither of whom ever made recordings for Nipper to listen to. An inquisitive dog, Nipper would, however, sit for long periods of time, one ear raised and his head cocked at an angle, studying whatever it was that attracted his attention. Francis's brother, Phillip, a professional photographer, had captured Nipper on film in such a pose. Francis ultimately disclosed that seeing one of these photos is what gave him the inspiration for the painting which was created in 1893 or 1894; nobody knows for sure.

The original painting was Nipper listening to an Edison-Bell Consolidated Phonograph Company cylinder machine, not a gramophone; yet despite this the distributor refused to purchase Barraud's masterpiece. Disappointed, Francis let the painting hang around the studio for more than five years, finally deciding to copyright it by having Phillip take a photograph of it for submission to the Copyright Office. This was in 1899, and immediately afterwards Barraud found another opportunity to sell it.

Nipper Is Sold

A friend suggested that the painting might be more saleable if the ugly japanned-black trumpet were re placed, however unauthentic it might be, with one of the smart looking horns used on the new Berliner gramophones. So Francis went to see William Barry Owen, who'd been sent by my grandfather to found British Gramophone. Astutely, Owen advised Barraud that the company was in the disc business, not cylinder, and thus if Francis were able to replace not just the horn but the entire Edison machine with a Berliner disc gramophone.

Owen would buy the painting ... for £50 plus £50 more for the copyright.

Interestingly, Barraud had brought with him only one of Phillip's photographs, and not the painting itself to show Owen, but this was more than enough to convince Owen of the design's commercial value.

Nipper was a great hunting dog and a strong adversary who'd think nothing about taking on a dog twice his size. In fact, it was difficult to get the hound to release his hold if he ever sank his teeth into you. In 1893, about the time the painting was created, Francis Barruad moved to Kingston-on-Thames.

Nipper died there two years later, in September at age 11, and was buried under a mulberry tree at the back of Mayall's Photographic Works.

On September 18, 1899, exactly five years after Nipper's death, Francis received from William Barry Owen the model he would use to shape the course of history . . . what was to become known as the "trade mark model" Berliner Gramophone, the third in a series of designs created by Emile and the model which introduced Eldridge Johnson's spring-wound motor that made constant cranking un necessary. Exactly one month later the finished painting was delivered to the Gramophone Company offices and was already titled by the artist, "His Master's Voice."

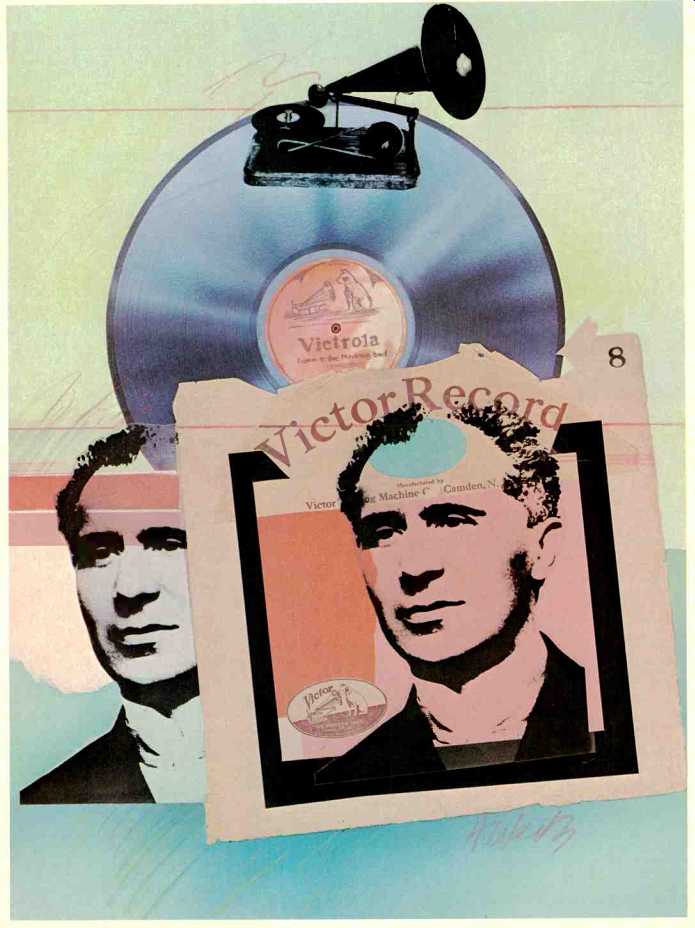

top: Oliver Berliner stands with the trademark model Berliner Gramophone

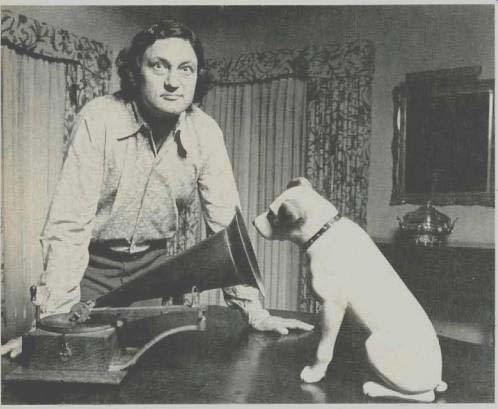

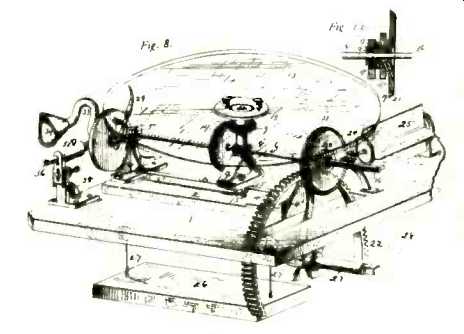

and a paper maché Nipper. middle: This is one of the sketches that accompanied

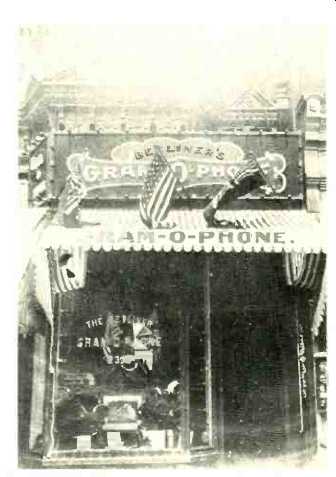

Emile Berliner's 1877 patent application, and (above) shown is the front of

one of the company-owned Gram-O-Phone stores in Montreal, Canada.

The HMV painting was reproduced immediately via lithographs made by Rembrandt Intaglis Printing Company, and were shown in stores owned by Gramophone Company. Nipper truly rocked the record business, to such a great extent that the company's real name became promptly obscured, and the firm became known as His Master's Voice, as it is today. Though not great art, the painting has majesty and is truly awesome when you consider its contemporary impact and the fact that, even today, it symbolizes the industry almost as much as it does its owners. (In fact, HMV has three owners: Nippon Victor for Japan, no relation to RCA Victor, and EMI for the rest of the world, except for the Americas where it is owned by RCA which now has relatively little interest in HMV but zealously guards against any possibility of losing it.) When Emile Berliner was visiting his English facility he was exposed to the Nipper painting for the first time, and he immediately carried the idea one step further. Where Owen saw Nipper only as an attention-getter, grandpa envisioned him as a trade mark. So, on July 10, 1900, Nipper joined the ranks of the immortals. British Gramophone, however, was loathe to acknowledge HMV as its trade mark, for they were attached to their design of a "recording angel," but about eight years later they succumbed to the inevitable. Barraud was several times commissioned to paint replicas of his original (minus the cylinder phono beneath the gram phone), but made very little money and lived in obscurity. Recognizing its oversight, the HMV Company instituted a pension for the old gentleman, £250 annually and later in creased to £350.

Yesterday and Today

From the time Nipper took the world by storm, the record business has been a strange one. There are today no company-owned stores, whereas in the old days a customer could walk right into HMV's shop and ask what was new on the label. Railroads had no freight classification for records and players, and categorized these items as dynamite, thus charging the highest rates. My father, Edgar, finally persuaded the carriers to regard his products as musical instruments, like pianos. Incidentally, he had the distinction of being president of all three successive Canadian companies . . . Berliner Gramophone, Victor Talking Machine Co., and RCA Victor, from which he resigned in 1929 as did many record-men who didn't want to work for the Radio Corporation whose goal was to promote radio using Victor's manufacturing capabilities, distribution ... and trade mark.

Because of the fact that three quarters of all single records released and 60 percent of all pop albums are financial failures, all recording artists today are paid on a royalty basis, with the top stars easily capable of grossing a million dollars annually. Royalties may be anywhere from six to 20 per cent of the suggested retail price of the record. Recording sessions are nothing short of astronomical, but the diskeries don't discourage this because they generally feel that the more that is spent, the better the master recording will be ... and the recording costs are deductible from the royalties earned by the artists. Nowadays, it is not un common for an album which should have required six to eight hours to pro duce to take six to eight weeks instead-sometimes more-and cost $30,000 to $75,000 for studio, musicians, arrangers, et al.

Once the late, and not too lamented, David Sarnoff, head of behemoth RCA, had boasted how he would "handle" James C. (for Ceasar, and not without cause) Petrillo, then head of the dreaded American Federation of Musicians, who by the way, never ever shook hands. The outcome of " Davie's" uncanny prowess was the best deal the musicians had gotten out of the record companies in history.

Subsequently, negotiations between the labels and the union have been handled by a trade group called the Recording Industry Association of America, just as is done in the movie industry by the Association of Motion Picture Producers. But unlike AMPP, the RIAA does not have an overpowering compulsion to keep the cost of musicians' services down. You see, diskeries come out of the woodwork daily with hundreds of low-budget garage operations born, while an equal number fade into oblivion annually.

Obviously, if the cost of recording sessions is high, fewer of these upstarts will be able to afford it. Simple, eh?

above: Society ladies and gentlemen dancing to the strains

of a waltz played on a Berliner gramophone along the banks of the Rhine in

1911.

Unions and Royalties

But, you say, the record labels also must pay these exorbitant recording costs (which include $80.00 to $150.00 per hour of studio time). They do? Don't be so sure. While it is true that the cost of musicians, orchestrations, studio facilities, and "amenities" is paid by the record firm producing these "sessions," these costs are all charged against the featured artist's royalties. So, despite the fact that the artist is the one who ultimately pays the recording session costs, he is not privileged to have a say in determining the rates he must pay for backup musicians ("sidemen") and supporting services.

As a consequence of all this, the "bootleg" session has long been on the scene. Here union musicians willingly work at reduced rates without the knowledge of their union because it's good money and nicely supplements their income ... to say nothing of the fact they are aware that a fledgling producer shouldn't have to pay the same wage scale as that of a well-established label--especially when the unknown was really being forced into contractual requirements that were set for him in absentia by the RIAA of which he isn't even a member (few record labels are). There are various "safe" studios in each of the major union-controlled production centers of America-Hollywood, New York, Nashville, Montreal-whose names are legion wherever bootlegging is known. Despite an occasional "raid" by a union steward, these recording studios are generally left alone, perhaps tacit testimony to the fact that the union is aware that its membership derives considerable employment thusly. Better that they work in this manner than have no work at all, right? Royalties were not always the rule in the record industry; originally artists were paid a fixed fee, depending upon their stature. Sir Harry Lauder is the one to thank for getting royalties started. The great Scot's HMV contract was up for renewal, and he was in a commanding position. He told the Gramophone Company that if they wanted him to record for them in the future it would have to be on a royalty basis-plus royalties on all the records sold in the past! Nipper howled in pain. They paid, and from that moment on the artist was king.

above: Four record presses were imported from the United States in

1898 to start production of "Gramophone" records in Hanover, Germany,

Berliner's birth place.

Neither movies nor television in their respective heydays can match to day's phenomenon, the rock groupie--the record business equivalent of the Judy Garland fan of yore. By a stroke of good fortune, I have frequent occasion to drive past one of the palatial residences of no less a figure than the late Elvis Presley. Although his majesty, even before his recent death, had long ago vacated the premises upon termination of his celebrated matrimonial alliance and had moved his famous hips back to Memphis, his yesmen were still ensconced in the Monovale Drive Taj Mahal on that transitional strip between Beverly Hills and Bel Air known as Holmby Hills, the district now presided over by Hugh Hefner. Apparently there to keep the place in good order until a realtor could unload it for Elvis, the yesmen saw no reason to forego the privileges of their rank . . . especially with nobody there to supervise them. Consequently, nearly every night an array of groupies stealthly parked their cars out in front of those massive gates, waiting-often in vain-for a call on the gatehouse intercom that would signal their permission to enter those hallowed grounds.

I'd been hopeful of latching onto one of the leftovers from time to time, but scrutiny revealed that virtually all were fat and acned. I asked one girl why she waited day after day. She momentarily stopped peering through the hedge to inform me that she'd been invited in once and it was fantastic. I inquired as to how it could possibly be so great with Presley absent. She indicated that she was quite content to settle for a yesman because this made her feel close to "him." Soon boys began to be present in considerable force, presumably to grab off any girls who didn't meet the entrance requirements. The police had to erect "no littering" signs, probably demanded by the neighbors who had been unsuccessful in getting rid of the groupies under the anti-loitering ordinances.

I've seen them standing outside in the rain at one-thirty in the morning. In good weather they wile away the tedious hours tossing a football back and forth. They congregate in the mid dle of the street and only with great reluctance will they budge, and then just slightly, to avoid being struck by passing automobiles. I've seen middle aged women rummaging through the garbage cans, perhaps desirous of finding a pair of discarded undershorts. Now that's the real showbiz we all know and love. The record industry has truly come of age.

Promotion and Promotions

Despite the fact that records are the oldest of the professional home entertainment media, the disc business has always been the least sophisticated of them all, particularly in the realm of advertising and promotion. For decades the industry was content to ally itself with its arch-enemy, radio, coupled with some co-op newspaper advertising with selected powerful retailers, as the virtual sole source of promoting its artists and their recordings.

But when Hollywood's fabled Sunset Strip became "hippie haven" a few years back, some sharpie decided that a judiciously placed billboard might prove its worth. Today if you're not a diskery, you'll find tough sledding in securing an available billboard along "the Strip." And the degree of puffery and press-agentry knows no bounds, what with spectacular lighting, special display materials, and three-dimensional designs that run the gamut from tasteless to distasteful. Whereas the Nevada casinos used to be Sunset Strip's principal contributors, today all the mafia-men's muscle isn't enough to do battle with the recordmen.

Spurred on by the first bloodletting on the Sunset Strip yet wary of the payola problems of radioland, the diskeries have plunged headlong into the promotional fray. They work actively with concert promoters and rock-nitery operators. They fight to get a new artist on the same program with an established headliner. They buy window space at major record dealers.

They make promotional tie-ins with unrelated products, sometimes using records as premiums. They've expanded into motion picture making and tele-production. Most all record labels own one or more music publishing companies, often in association with their important recording artists, for they want to pay themselves that penny-a-disc royalty that normally goes to the copyright proprietor ... to say nothing of the performance royalties earned by the writers and publishers when a song is played on the air (live or in recorded form), in nightclubs, arenas, ballrooms, and even in parades up New York's Fifth Avenue.

In fact, the independent music publisher not affiliated with a record label or major artist today couldn't even get himself arrested because the artist and/or his record company want to own the songs they record. Certain major artists won't record a song they don't "have a piece of." Many times they even have the audacity to demand that their names be listed among those of the songwriters.

Diskeries "Peter Principle"

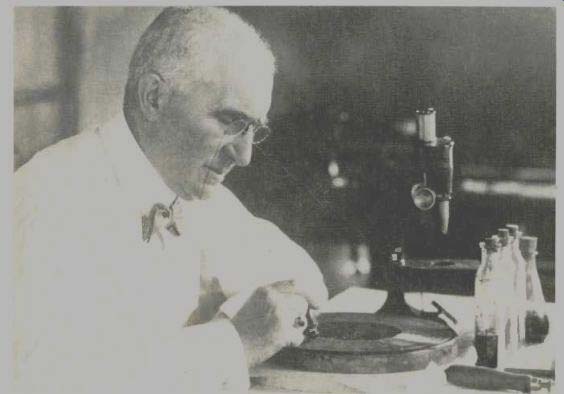

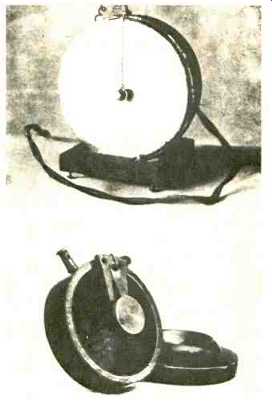

(top) Emile Berliner examining the grooves on a newly cut disc

for imperfections. (middle) This year also marks the 100th anniversary of

Berliner's invention of the microphone, with the original model of March

4, 1877 at top, while the other is the telephone transmitter which, with

the mouthpiece added, saved the Bell System from ruin. (above) The infant

Deutsche Gramophone Co. of 1898 with just a few machines and handful of workers.

But for all their newfound sophistication, the record companies still lack a knowledge of people. Job hopping is rampant, even in the highest echelons, and the man who's gotten his name in Billboard the most times is the one who's thought of first when a position opens up at a label. I recall a couple of guys who were responsible for a privately owned firm's losing a couple of million dollars and going bankrupt in a brief period of time, and within the blink of an eye turning up at an even larger diskery where they immediately proceeded to do the same thing. One of them even thought nothing of listing his earlier catastrophe in his resume when he joined the next firm. Another guy, whose bad judgment helped wreck a label so that he was forced out, had no trouble getting himself an even more prestigious job in a trade association ... where presumably he couldn't do any harm ... all because of personal publicity he'd garnered in the "trades." Then there's the sound technician who'd been earning a couple hundred dollars a week in a small independent recording studio. He had the good for tune to mix a recording session which resulted in a then-pennyless artist being skyrocketed to fame and fortune.

As a reward, this technician was hired away to manage the artist's own new recording studio. Being merely an equipment operator, the technician suddenly found himself cast not only in the role of a manager and administrator, but a studio designer as well. His first efforts were a total wipeout, but with the artist earning so many millions that the government paid the bulk of his losses in the form of expense write-offs, and the technician (today unemployed) continued to earn tens of thousands of dollars annually, drive a Cadillac, and at the drop of a hat would proudly show you his $350.00 digital readout wristwatch that he'd bought before they flooded the market at a mere $50.00. And you thought this sort of thing happened only in the Hollywood movie industry's halcyon days, eh? But, most inexplicable of all was the case of Sal lannucci ... so audacious, even by showbiz standards, that NBC's Rowan and Martin couldn't resist taking a poke at one "Salvatore Anuchi" on an episode of their show "Laugh In." lannucci had been a second-string, resident legal counsel at CBS in New York City. No one in the record industry had ever heard of him and, apparently, few people in broadcasting had either. Incredibly, out of the shadows he suddenly emerged as, of all things, President of Capitol Records. Today, while Salvatore is safely ensconced elsewhere, industry observers are still trying to figure out this miraculous ascendency to "Cap's" helm and what relationship he may have had to that diskery's continuing troubles. Interestingly, more than one Capitol bigwig has used his short-lived tenure there as a stepping stone to even greater glory (hopefully, in less volatile atmospheres).

Piracy--Then and Now

Thanks to the advent of magnetic tape and the considerable consumer acceptance of recordings in this form rather than on disc, record piracy has risen to major proportions, siphoning off untold tens of millions of dollars rightfully belonging to the recording artists and their respective record labels, music publishers, and composers. Sophisticated pirates using the finest of equipment secretly stashed in unobtrusive locales, not only avoid the difficulties in copying from disc to disc (most of this having been done in the Phillipines in the not-so-good old days of counterfeiting), but even have brazenly offered to pay royalties to all parties involved. But it must be remembered that these crooks make no investment in the costly recording session, take no risk, because they copy only the hits, and spend no money in building the stature of a heretofore unknown artist nor in promoting the sale of his records.

A lot of water has gone under the bridge since the time Eldridge Johnson, with an assist from Emile Berliner, launched the Consolidated Gramaphone Company in Camden, New Jersey, soon afterwards to be renamed the Victor Talking Machine Company (incorporated Oct. 13, 1901) in recognition of my grandfather's court victory over a former employee, Frank Seaman, who, in cahoots with a slick lawyer for Columbia Graphophone Co., Phillip Mauro, had used an obscure legal loophole to challenge the inventor's right to manufacture his own records and players. They'd miraculously obtained an injunction preventing grandpa from continuing in business. But Johnson, a top-flight machinist who'd developed the spring-powered turntables used in the trade mark model Berliner Gramophone, persuaded grandpa that he should be allowed to make discs and talking machines until the lawsuit was re solved. He then talked the court into voiding the injunction brought against him.

Emile Berliner won a year later, but was financially ruined, while Johnson was enjoying considerable success not only in filling the demands of the domestic market, but also in furnishing turntables to British Gramphone as well. Victor quickly became the most powerful label in the world, aided in no small way by the use of grandpa's trade mark of the little dog listening to his master's voice on the gramophone.

It has truly been stated that, "If Eldridge Johnson be king of Camden, Emile Berliner crowned him so." Johnson enjoyed his newfound prosperity in regal splendor, particularly aboard his palatial 171-foot yacht, the Caroline, reputedly purchased for nearly a half-million dollars in the late 1920s. My father, Edgar, who headed Montreal's Berliner Gramophone, which became part of Victor in 1924, loved to tell of the directors' meetings Mr. Johnson liked to hold on board.

One time Mr. Johnson asked the steward (the ship required a crew of 30) to pass out cigars after lunch. But before the men could light up he stopped them, saying he wanted to continue the meeting out on deck and since these cigars were too good to be "wasted" outdoors, he'd have the steward pass out some cheaper cigars.

The cheaper ones were Corona Coronas selling in 1927 for $1.00 each! Nowadays Victor, owned by RCA since 1929, with said purchase being closely followed by the death of Emile Berliner and nearly that of the stock market as well, is not the supreme leader it once was, Warners and Columbia Records having long ago taken over dominance of the industry. Decca has been swallowed, and dropped, by upstart MCA (Universal Pictures).

Other labels, unknown in the days of yore, have risen to prominence such as WEA (Warner-Elektra-Atlantic), and little powerhouses such as A&M and Mo town have flexed their new muscles, with a host of other upstarts nipping at their heels.

Perhaps the following anecdote correctly characterizes the record business in a nutshell. Decades ago a number of Canadian Victor officials were visiting British Gramophone.

They'd checked out of their hotel and had brought their luggage to the Gramophone Co. offices at Hayes for a final conference prior to catching the boat-train. Realizing they were late and unable to find a taxi, one of the group spied a group of workmen digging a ditch. With a wink at his associates, he sauntered over to the ditch-diggers and, affecting a (phony) British accent, asked, "I say, old chaps, would you mind carrying our bags down to the railway station? We're from His Master's Voice." With this, one of the workmen looked up and exclaimed in a typically British (understated) tone, "Oh, f_ _ _ His Master's Voice!" Whereupon the ditch-diggers proceeded to chase the group down to the station. Enough said.

-----------

(adapted from Audio magazine, Dec. 1977)

Also see:

Phonograph Reproduction --1978: part 1 (May 1978)

Phonograph Reproduction --1978: part 2 (Jun. 1978)

Recordings for Critical Listening (Jan. 1978)

= = = =