Manufacturer's Specifications

Frequency Response: 4 Hz to 20 kHz, ±0.1 dB.

Dynamic Range: Greater than 96 dB.

S/N: 106 dB.

THD: 0.0025% at 1 kHz, 0-dB level.

Channel Separation: 106 dB at 1 kHz.

Channel Phase Balance: Less than 5°.

Number of Programmable Se lections: 20.

Output Voltage: 2.0 V (at 0 dB).

Output Impedance: 200 ohms.

Recommended Load Impedance: More than 10 kilohms.

Pitch Control: ±8%.

Power Requirements: 120 V, 60 Hz, 29 watts.

Dimensions: 16 15/16 in. W x 6 3/4 in. H x 14 15/16 in. D (43 cm x 16.8 cm x 38 cm); 9 1/16 in. H (23 cm) when disc compartment is open.

Weight: 32 lbs. (14.5 kg).

Price: $1,300.

Company Address: One Panasonic Way, Secaucus, N.J. 07094, USA.

Although most audio enthusiasts have finally conceded that the Compact Disc and CD players can deliver sound quality equal to or better than any other program source yet devised, there's one group of people who still find fault with the new medium. No, they aren't debating sound quality;

their problem is purely mechanical. I'm speaking about professional disc jockeys who work at radio stations, discos, and the like. Their complaint is that they are unable to cue up Compact Discs with the same precision that they can achieve manually with LP records. Indeed, that's true. I've heard many a broadcast in which the desired CD track was preceded by the last second or two of the previous track, or in which the first note or two of the desired track was missed.

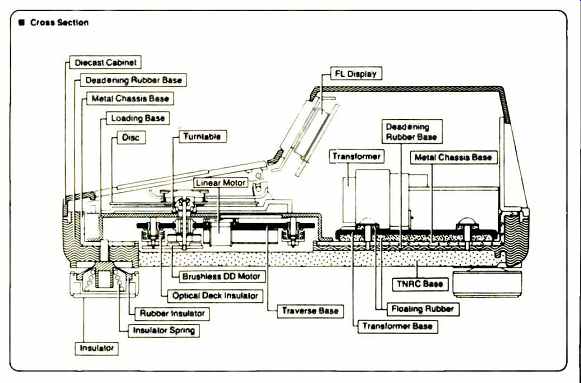

Fig.

1--Cross-section view of SL-P1200 construction. (TNRC: Technics non-resonant

compound; DD: Direct drive.)

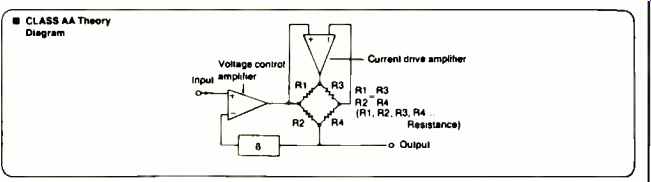

Fig. 2--Schematic diagram of Technics Class-AA circuitry.

Now Technics has come to the rescue of these professionals. In doing so, they have produced a CD player that will appeal to many serious audio enthusiasts as well. The SL-P1200 is one of the most feature-laden and best-per forming players that I have seen to date. The engineers who designed it must have been told to forget about costs and simply come up with a player which is as resistant as possible to external or internal vibration and shock and which takes advantage of every bit of subcode data on the Compact Disc.

Just consider these features: By turning a smoothly rotating dial with your fingertip, you can cue forward or back ward in precise 0.1-S increments at two search speeds. A switch lets you "lock out" this feature to avoid accidental mis-cueing. Beyond that, there's an auto-cue button which, when pressed, finds the beginning of actual music at the start of a track. Since a delay of a second or two often occurs between the time a track starts and the time the music begins, this is especially useful for tight, precise cueing. The fast-search keys, in addition to performing their normal audible-search functions, allow you to shift the laser pickup forward or backward one pit track (about 0.1 S) while in play or pause mode. This facility reminded me of the reel-rocking capability of reel-to-reel tape recorders; Technics has even labeled the keys "Rocking/Search." Here's another problem addressed by the SL-P1200: Have you ever wanted to play (or record onto tape) a disc that ran, say, 45 minutes and 22 seconds, when you had exactly 45 minutes of time or tape to work with? No problem, with this machine! Its precise pitch control allows you to vary pitch (and therefore playing time) by as much as 8% in either direction. That's something which can be done on many professional turntables, but only a very few CD players have the same capability, and the few I've seen didn't have calibration scales as accurate as the one provided on this unit.

Of course, all of the usual CD features are here too, such as 10-key direct access to tracks or index points. You can access by time too, in 0.1-S increments. Random programming by track number is also available, with memory of up to 20 tracks. You can repeat a single track, the entire disc, or a memorized random program. If you are recording a CD onto tape, an "auto-space" function adds 3 S of silence to whatever gap already exists between tracks. This helps the music-search systems on many tape decks and car players find where each track begins on the tape, and the feature can be used even when playing back a memorized pro gram. "Skip" keys are provided for moving quickly from track to track.

Construction and Circuit Highlights

A cross-section of the SL-P1200 is shown in Fig. 1. To suppress airborne vibrations, the base uses a metal chassis with a special damping rubber and a proprietary non-resonant compound. This combination of materials converts vibration into thermal energy while providing stability and strength without causing secondary resonances. The cabinet is made of a zinc die casting with vibration-damping material between it and the three-layered base. Four large rubber insulators and coil springs help block out vibrations that might be carried through the platform on which the player rests. Inside, double insulator construction floats the optical deck, isolating it further from vibration. Power transformers are floated in a rubber damping material to avoid vibrations at power-line frequencies.

Fig. 3-Frequency response, left (top) and right channels.

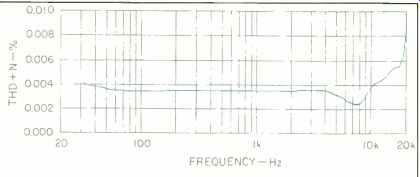

Fig. 4-THD + N vs. frequency at 0-dB recorded level.

Some time ago, Technics developed an audio amplifier circuit which they call Class AA. Featured in the company's high-end amplifiers, this circuit tends to avoid the influence of speaker load impedances upon the performance of voltage amplifier stages. In the SL-P1200, Class-AA circuitry is used in the sample-and-hold circuits and in the buffer amplifier. The sample-and-hold circuit is placed after D/A conversion, where it removes switching noise from the signal.

Here, the Class-AA circuitry is used for isolating the voltage-control amplifier from the current-drive amplifier which charges and discharges the capacitive load that follows.

This isolation enables the voltage amplifier to transfer the CD format's high-density data to later circuits with greater accuracy, according to Technics. In the buffer amplifier prior to the audio output, Class-AA circuitry serves to isolate the voltage-control amplifier from the preamplifier and from the capacitive loads it would encounter in the connection cables. (A simplified diagram of the Class-AA circuit is shown in Fig. 2.)

Dual D/A conversion is used in this player, as are two-times oversampling and digital filtering.

Fig. 5 Spectrum analysis of 20-kHz test signal. Sweep is linear from 0 Hz

to 50 kHz.

Control Layout

The SL-P1200 housing is shaped like a small studio con sole. User controls and the top-loading disc compartment are up front, on a gently sloped horizontal surface; the major display area and power switch are on a more sharply sloped vertical section toward the rear of the unit. The centralized multi-function display has, first of all, a nine-digit readout showing track number, minutes, seconds, and tenths of seconds. When level attenuation is operated from the supplied remote control, attenuation is shown in decibels. A "music matrix" of 20 illuminated numerals indicates program content and the track being played. There are also indicators for repeat, standby, auto-cue, music scan, elapsed/remaining time, and track/total time. If a disc re corded with pre-emphasis is played, that fact is also indicated at the extreme right of the display area.

The disc compartment occupies the left side of the SL P1200's front sloped panel. To the compartment's right are the numeric keys used for track and index accessing and for programming the player. Forward and reverse "Rocking/ Search" buttons, forward and reverse "Track Skip" buttons, "Stop," "Pause," and "Play" buttons are also found here, as are the "Repeat," "Auto Space," "Index," "Clear," "Memory," and program "Recall" buttons. A "Time Recall" button confirms starting time when playing a disc from a specific point.

Farther to the right are "Auto Cue" and dial "Search" buttons, "Time Mode" buttons, the large search dial itself, a two-position dial-search speed button, a slider control for pitch adjustment, and a "Pitch Control" on/off button. Even with activation of the pitch control, you can return to correct pitch by setting the slide control at its midpoint, which has a detent for easy location. For precise operation, the search dial has a depression near its edge into which the tip of a forefinger fits. A headphone jack and an accompanying headphone-level slider control are near the right end of the player's front apron.

The rear panel of the SL-P1200 has the usual pair of gold plated output jacks plus a pair of DIN-type connectors. One of these connectors provides subcode output for future use with CD-I or graphics interface boxes; the other is for wired remote control. A schematic in the owner's manual shows how a wired remote can be built to handle play, pause, and stop functions. I'm not quite certain why anyone might want to wire up such a remote for home use, in view of the fact that a multi-function wireless remote control (which does much more than those few basic functions) is supplied with this player. In a studio or other setup where you want to operate the unit remotely but do not have a direct line of sight from your listening position to the player's infrared sensor, I suppose a wired alternative would be useful. (A studio version with wired remote and balanced outputs, the Model SL-P1200X, is available for $1,500.) Incidentally, one function of the supplied remote control, digital volume attenuation, is not found on the player itself. This can be used to change output level in 2-dB steps from 0 to-12 dB. All settings of the attenuator are shown on the main unit's display.

Fig. 6--S/N analysis, both unweighted (A) and A-weighted (B).

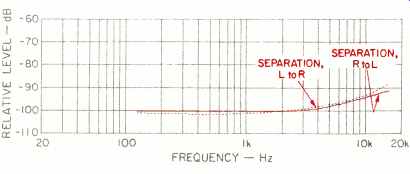

Fig. 7--Separation vs. frequency.

=============

DITHERED LINEARITY CD TEST SIGNALS

In any digital audio system, the quantization process produces errors in the output waveform. These errors are constant in level, s0 their relative magnitude increases as the signal level decreases, even if the D/A converter is perfectly linear. In order to accurately judge the linearity (or non-linearity) of a particular D/A conversion system, it is necessary to add an appropriate amount and type of dither to the test signal.

Dither is simply a form of low-level noise. Specifically, it is of constant level (half the signal amplitude that would be encoded by the digital signal's least significant bit) and of randomly varying frequency.

On the new EIA CD-1 test disc, two series of signals have had such noise added to the original sine wave be fore quantization. The spectrum of the resulting test signals on the disc therefore consists of a signal component. at the reference frequency and the specified level, superimposed upon a low-level signal containing random frequencies from 0 Hz to 22.05 kHz at equal levels. With this set of test signals, it becomes possible to demonstrate that digital audio is capable of reproducing signals at any level, including those well below an amplitude of 1/2 LSB (least significant bit). The dithered test signals extend from -60 to -100 dB.

=============

Measurements

Figure 3 shows frequency response of each channel as reproduced from the sweep tracks of the EIA CD-1 test disc.

Maximum deviation from perfectly flat response at 20 kHz was -0.3 dB on one channel and -0.4 dB on the other.

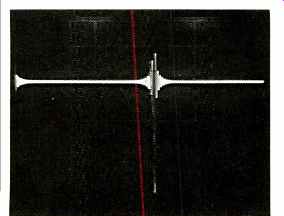

Harmonic distortion at maximum recorded output level measured only 0.0035% at mid-frequencies, but what's really remarkable is the fact that without using any low-pass filters whatever (or at least none with a cutoff below 80 kHz), THD+ N at 20 kHz measured only 0.009%. Figure 4 shows how THD + N varied with frequency. If you have been following my CD player test reports, you know that non-harmonically related out-of-band components for most players often result in 20-kHz THD + N readings several orders of magnitude higher than this. The absence of spurious components (out of band or within the audio band) is clearly evident from the 'scope photo of Fig. 5; the only output seen is the desired 20-kHz test signal itself, with not a trace of anything else on either side of it! Figures 6A and 6B depict the results of the S/N analysis that I performed using the "silent" track of my EIA test disc.

Unweighted S/N measured 92.7 dB, and A-weighted S/N was 97.6 dB. Dynamic range, measured in accordance with the recently suggested EIAJ method, was a remarkably high 114 dB.

A newly suggested EIA method for measuring dynamic range, however, yielded a more conservative result of 97.5 dB. This method requires a dithered 500-Hz test signal altered from 60 to 120 dB below maximum recorded level.

To reject noise, the player's output is then passed through a 1/3-octave filter tuned to 500 Hz, and the output at the two test levels is measured in dB relative to the output at maxi mum recorded level. In practice, these two output levels will be less than 60 dB apart since, because of the dither added to the signal, no player is actually capable of reproducing a signal at-120 dB. The ultimate determination of the noise floor is made by finding the recorded signal level for which the player's output is 3 dB above the reading obtained for the-120 dB level on the disc (the dithered noise level).

This signal level (N) is the lowest which can reliably be distinguished from the player's background noise.

Maximum signal level is 60 dB above the output reading for the- 60 dB test tone (R), and from this one subtracts the output level recorded at 3 dB above the noise level (N). In other words, dynamic range is defined as 60 + R- N. I will be using this new procedure for measuring dynamic range in all future test reports of CD players.

Stereo separation was superb, approaching or exceeding 100 dB at all but the highest frequencies, as shown in Fig. 7. These results include any crosstalk that may have occurred between output cables in my measurement setup.

It is quite conceivable that if the cables had been eliminated, I could have easily achieved the claimed separation figure of 106 dB.

Linearity was measured in two ways. For undithered signals, linearity was accurate to within 1.1 dB down to-70 dB. Using a dithered test signal in the range from- 70 to-100 dB, I was able to read down to -96.5 dB (see sidebar). SMPTE-IM distortion for this player measured 0.0085% at maximum recorded level, and CCIF-IM distortion, using twin tones of equal amplitude separated by 1 kHz, was 0.0045% at maximum recorded level and 0.0016% at-10 dB.

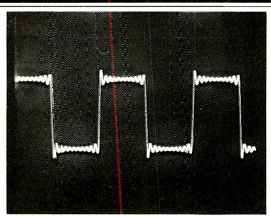

Figure 8 shows a 1-kHz square wave reproduced by the SL-P1200; it is typical of those reproduced by all CD players that employ digital filtering and oversampling. The same holds true of the unit pulse depicted in Fig. 9. Note, how ever, that this player does invert signal polarity. Finally, the Lissajous pattern of Fig. 10 confirms the fact that two D/A converters are used in this player: There is no evidence of any time or phase displacement between left and right 20-kHz output signals.

Fig. 8--Reproduction of a 1-kHz square wave.

Fig. 9--Single-pulse test.

Fig. 10--interchannel phase comparison at 20 kHz. Straight line indicates

absence of time or phase error.

You probably won't be surprised to learn that the SL P1200 had absolutely no trouble tracking the various sections of my "defects" test disc. Furthermore, external vibration of rather large magnitude caused no mistracking of any of the discs I used during subsequent listening tests. This player is one of the most ruggedly built units I have yet encountered. It wag clearly designed to operate even in the most hostile environments, such as discos, where nearby dancing feet can set up quite a lot of mechanically borne vibration and deafening SPL levels can create airborne vibration that lesser players might not be able to handle.

Use and Listening Tests

What I found especially interesting about this unit was that, for all its professional features and its rugged construction, the sound quality delivered was superb, akin to some of the more delicate high-end CD players that I've tested. In other words, don't let the rugged construction, the disc jockey features, and the odd physical configuration fool you into believing that the SL-P1200 is suitable only for commercial applications. It's price is actually lower than that of some high-end home players that don't sound nearly as good.

In using this player, I discovered a couple of things that make it particularly attractive at this juncture in the evolution of CDs and CD technology. You've no doubt heard or read about the new CD "singles" that measure only 8 cm in diameter (about 3 inches) and contain up to 20 minutes of music. These tiny discs will require an adaptor if you want to play them on most drawer-loading players. If you own a unit such as the Technics SL-P1200, with its top-loading format and its centering spindle, no adaptor is required. In fact, two of the discs I used to audition the player were "singles," one from Telarc, containing four selections from their full-sized Pomp and Pizazz disc (CD-80122), the other a new sampler from DMP (Digital Music Products) containing three short selections in a more popular vein. I also listened to some longer works, including a recently acquired Deutsche Grammophon recording (three discs) of Mozart's "Magic Flute" opera (410 967-2). Voice reproduction was extremely accurate, and the sense of depth and placement of the opera orchestra relative to the singers on stage very closely duplicated the sensation I get when attending a live performance.

Having convinced myself that this unit's sound quality left nothing to be desired, I spent the rest of my auditioning time playing with its professional features. The search dial is especially well executed and works flawlessly, and each of he two search speeds is perfect for its particular application. At one point during my listening tests, I knew that a specific orchestral crescendo was a bit farther along in the rack. I selected the slow search mode and started turning he search dial to find the exact spot I wanted. At this speed, each rotation of the dial advanced the laser pickup by only about 1 S-great for really zeroing in on an exact note, but not good for my purposes. Switching to the fast search mode, one rotation of the dial advanced the pickup by about 20 S of playing time, which suited my needs exactly.

A couple of turns brought me right to the point I wanted, and a press of the "Play" button let me hear the phrase of music I'd been looking for. No other CD player I've worked with made accurate cueing quite this easy.

When I recall that my first CD player, back in 1982, had a suggested price exactly the same as this sophisticated professional unit's price, I am amazed at what has become possible in the mere five years that CD players have been available. Whether you are professionally involved in audio or are just a serious music lover, you'd do well to check out his amazing component.

-Leonard Feldman

Also see: Link | --Technics SL-P8 Compact Disc Player (April 1984)

Thomson CD Recorder -- Exclusive U.S. Test!!! (Mar. 1990)

(Source: Audio magazine, Dec. 1987)

= = = =