Manufacturer's Specifications:

Frequency Response: 2 Hz to 20 kHz, ±0.3 dB.

De-Emphasis Equalization: ±0.3 dB.

THD Plus Noise: Less than 0.003% at 1 kHz.

S/N Ratio: Greater than 120 dB.

Dynamic Range: Greater than 100 dB.

Channel Separation: Greater than 100 dB at 1 kHz.

Output Voltage and Impedance: 2.0 V, 47 ohms.

Headphone Output and Impedance: 280 mV, 150 ohms.

Number of Programmable Selections: 24.

Power Requirements: 120 V, 60 Hz, 25 watts.

Dimensions: 18 5/8 in. W x 5 3/16 in. H x 15 7/16 in. D (47.3 cm x 13.2 cm x 39.2 cm).

Weight: 35 lbs., 3 oz. (16 kg).

Price: $1,499.

Company Address: 6722 Orangethorpe Ave., Buena Park. Cal. 90620.

Yamaha has come up with their second-generation Series 2000 Compact Disc player featuring the company's Super Hi-bit technology and hand-selected, matched electronic components. The unit is distinctive looking, with a titanium finished front panel and walnut side panels.

Super Hi-bit technology consists of series-loaded, 18-bit D/A converters combined with four-floating-bit circuitry. Yamaha claims this achieves the effective linearity of a 22-bit system. (For more on the floating-bit approach, see my review of Yamaha's CDX-1110U CD player in the September 1988 issue.) To eliminate one source of noise spikes, the player uses series-loaded D/A converters rather than the more common parallel-loaded type. Four D/A converters are used, in a "balanced processing" system. In this system, the output of the digital filter is fed to two converters per channel, one of which operates in normal polarity while the other operates in inverse polarity. This design, according to Yamaha, achieves an excellent common-mode rejection ratio. The player also employs 20-bit digital filters with eight times oversampling, an LSI digital de-emphasis circuit, and a 20-bit digital volume control.

Shunt-regulated power supplies and independent transformers on separate circuit boards are used for digital and analog stages. The suspension and damping systems, and a new heavy-duty chassis, are said to minimize the effects of external and internal vibration or resonance.

Other features incorporated in the CDX-2020 include four-way repeat play (of the entire disc, a single selection, a marked segment, or a programmed sequence of tracks) and random play. Time readouts on the multi-function display are for total time, remaining time, elapsed time of the present track, and remaining time of the present track. Programming of up to 24 tracks is possible, as is direct track access via the player's front panel or the supplied remote control.

Control Layout

Yamaha has cleverly divided the operating controls into primary and secondary categories. The controls visible at all times on the front panel are a power switch, a headphone jack, an "Open/Close" button for the disc tray, a "Play" button, and a "Pause/Stop" button. Also normally visible is a large display window that shows track and index numbers, the various selected time displays, repeat modes, programming information, the output level setting (on a dB "meter" scale), disc emphasis (when applicable), and various other status indications. A "track calendar," consisting of numbers 1 through 24, runs along the entire lower edge of the display area.

When a hinged panel along the bottom right of the front panel is lowered, the many secondary controls are ex posed. At the far left are the display "Mode" button (which blanks all parts of the display except for time and track) and "Time" button (which selects total disc time, total elapsed time, or elapsed time within the track), followed by the buttons for repeat play. Next comes "Auto Space," which puts the player in pause for 3 S after every track; when transcribing CDs onto cassette, this ensures there will be enough blank space between tracks for a cassette player's search system to find them. To the right are the buttons for programming, "Random Play," fast search, track skip, and "Index." Along the bottom row are buttons for the numbers 0 through 9 as well as a "+ 10" button for accessing track numbers in the teens and higher. (I found accessing index points to be a bit awkward. When you push the button for indexing, the word "Index" begins to flash in the display, following which you must press the appropriate index number by using the number buttons.)

Finally, at the lower right corner of this control area are an "Up/Down" rocker switch for volume control and a "Hi-Bit Direct Out" button which allows bypassing of the analog output filters. This switch is used to determine whether the analog signals available at the player's output terminals should have no analog final filtering or if the signals should be passed through analog low-pass filters. Yamaha's D/A conversion system makes it possible to listen to the player even when no final filtering is used. However, in my measurements and listening tests, I perceived no particular advantage in doing so.

The supplied remote control duplicates every control on the front panel. The only difference is the presence of 24 numbered buttons in addition to the "+ 10" button; this allows still higher track numbers to be accessed.

The rear panel of the CDX-2020 is equipped with the usual left- and right-channel analog line output jacks as well as with coaxial and optical digital output terminals, should you want to use a separate D/A converter. In view of the excellent D/A conversion circuitry I found in the player itself, I can't see why anyone would go to the extra expense--especially since the digital-to-analog converters on those amplifiers which are so equipped have, in the main, proven to be no better than the D/A conversion systems in players such as this one.

Measurements

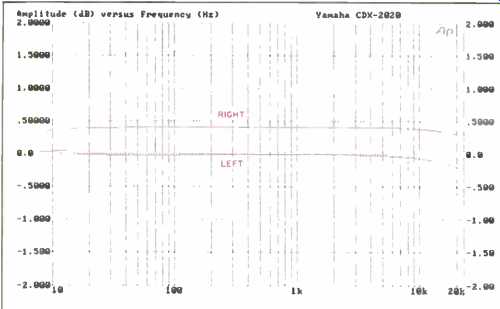

Fig. 1--Frequency response; see text.

Figure 1 shows the frequency response of the Yamaha CDX-2020, plotted from below 10 Hz up to 20 kHz. While response was certainly well within the tolerance limits specified by Yamaha (it was off by no more than-0.2 dB at 20 kHz), I was surprised by the difference in output level between the left and right channels. The right channel's output was nearly 0.4 dB greater in amplitude than the left channel's. This condition can be easily remedied with the balance control on your amplifier, but in my sample, at least, it was surprising that tolerances of the analog output amplifier stages were not held closer.

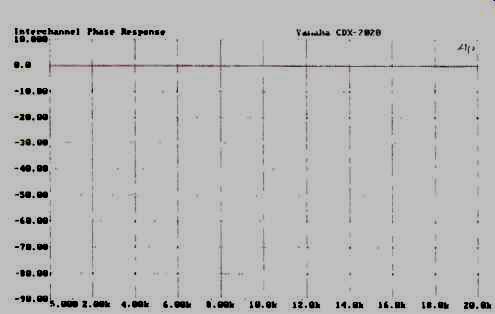

If outputs of both channels were not precisely equal in amplitude, they certainly were in terms of phase. As shown in Fig. 2, interchannel phase response was virtually perfect from 5 Hz to 22 kHz-that is, the signals from both channels were perfectly in phase, within a fraction of 1°, at all measured frequencies.

Fig. 2--Interchannel phase response, from Hz to 22 kHz.

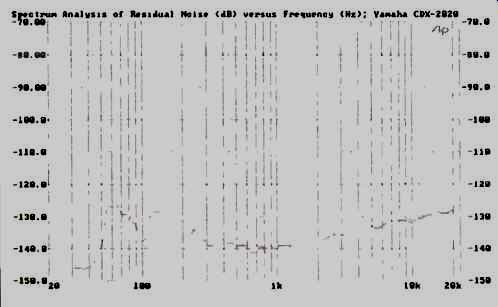

A-weighted signal-to-noise ratios were among the highest I have ever obtained for any CD player: 123.7 dB below maximum recorded level for the left channel and 122.5 dB for the right channel. Figure 3 is a spectrum analysis of residual noise emanating from the player when I played the "no-signal" track of my CBS CD-1 test disc. Even at the power-line frequency of 60 Hz, noise was more than 125 dB below maximum recorded level.

Fig. 3-Residual noise vs. frequency for "quiet" track of CD-1 test

disc. Note low noise level at 60-Hz power-line frequency and its multiples.

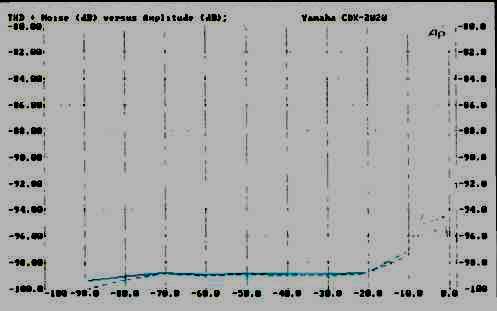

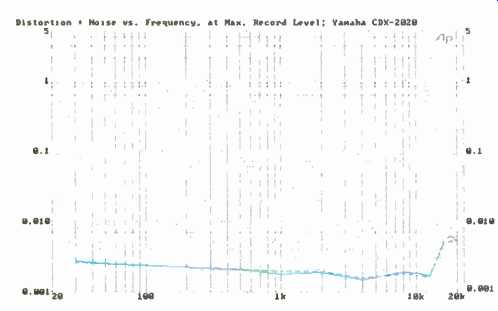

Figure 4 shows how THD + N varied as a function of output level. Plotted values are recorded in dB relative to maximum recorded output level, which is defined as 0 dB. Over most of the range from -90 to -20 dB, THD + N was 99 dB or greater. Expressed as a percentage, this corresponds to 0.0011%. At levels approaching maximum recorded output, the analog stages obviously were responsible for a very slight increase in THD + N; readings around the 0-dB level were approximately -95 dB. Again expressed as a percentage, this amounts to 0.0018%. Figure 5 shows how THD + N varied with frequency for signals at maximum recorded level. There was excellent correlation between this test and the test shown in Fig. 4. At 1 kHz, THD + N was below 0.002%, while at 20 kHz, it rose very slightly, to around 0.005%. (Remember when early CD players exhibited THD + N readings of as much as 1% at 20 kHz? Most of those readings were caused by out-of band "beats"; no beats were detectable with this player.) I also measured SMPTE-IM distortion at maximum recorded level and found it to be 0.0051% for the left channel and 0.0053% for the right.

Fig. 4--THD + N vs. signal level for left channel (solid curve) and right

channel (dashed curve).

Fig. 5--THD + N vs. frequency for left channel (solid curve) and right channel

(dashed curve).

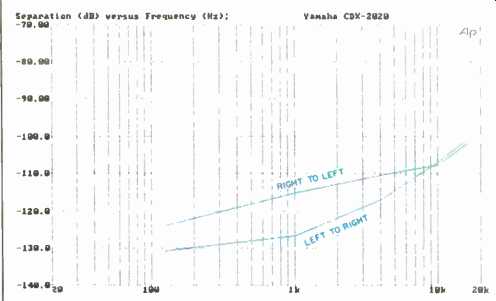

Fig. 6--Interchannel separation vs. frequency.

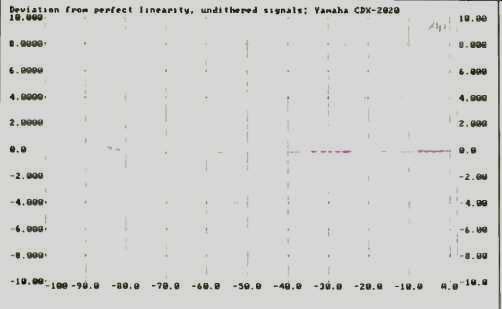

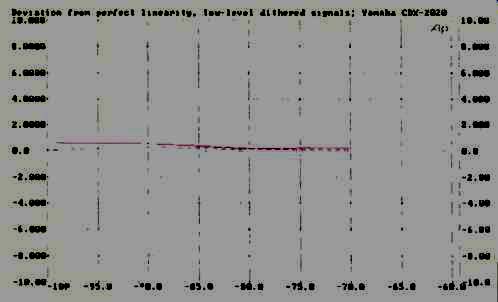

Although channel separation was not the same for left-to right crosstalk as it was for right-to-left (Fig. 6), in either case it was superb, remaining below 100 dB even at 16 kHz (the highest signal I have available for making this test). At 1 kHz, separation from left to right amounted to 127 dB; from right to left, it was 115.5 dB. As has been the case for several superb-sounding CD players recently, the chief distinguishing performance characteristic of the CDX-2020 was its excellent low-level linearity. Figure 7 shows that the deviation from perfect linearity at 90 dB below maximum recorded level, when the player was reproducing undithered signals, was no more than +0.8 dB for the left channel and just a bit less for the right. Results using low-level dithered signals, in the range from 70 to 100 dB, were even more remarkable. As shown in Fig. 8, deviation at 100 dB below recorded level was no more than +0.6 dB for the left channel and a negligible +0.2 dB for the right.

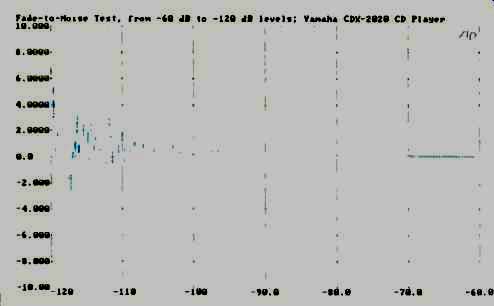

The superb low-level linearity and noise-free performance of this player were further confirmed when I plotted deviation from linearity using the fade-to-noise signal on my CD 1 test disc. In Fig. 9, you can see that the signal decreases in perfectly linear fashion right into the residual noise at 120 dB. From this graph it is also possible to determine the CDX-2020's effective EIA dynamic range, which was approximately 110 dB. If dynamic range is measured in accordance with EIAJ procedures, the results are lower, yielding 98.2 dB for either channel.

Fig. 7-Deviation from perfect linearity for undithered 1-kHz signal; solid

curve is left channel, dashed curve is right.

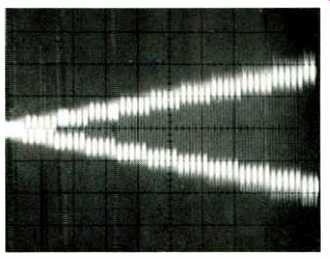

The last track of the CD-1 disc contains a test signal useful in checking the monotonicity of a player's D/A conversion system. Ideally, the "steps" of this square waveform should be equal in amplitude, for both positive- and negative-going waveforms, as the peak of the waveform progresses from "digital zero" and increases by one LSB (least significant bit) every five cycles to a maximum of 10 LSB. The results shown in Fig. 10 come about as close to this ideal as I have seen for any player.

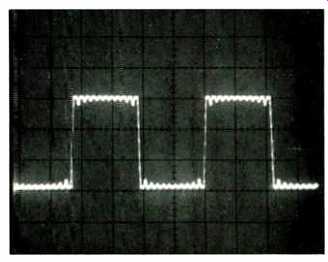

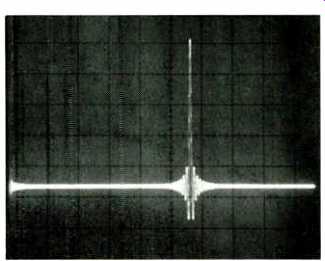

Clock accuracy, which in turn determines pitch or frequency accuracy of reproduced music, was-0.0046%. Figures 11 and 12 show how a 1-kHz square wave and a unit pulse were reproduced by this player. The polarity of the unit pulse output reveals that the CDX-2020 does not invert signal polarities.

Fig. 8-Deviation from perfect linearity for low-level dithered signals; solid

curve is left channel, dashed curve is right.

Fig. 9-Linearity deviation for "fade-to-noise" test of dynamic range.

Fig. 10--Monotonicity test.

Fig. 11--Reproduction of 1-kHz square wave.

Fig. 12--Single-pulse test.

I used a special Pierre Verany test disc to determine how well the Yamaha can track CDs that have missing data. For passages having normal "pitch" between them, this player was able to track signals in which a full 2 mm of the digital data was missing. That's almost three times the length of missing data provided on the Philips disc that I formerly used for this test! When track pitch was reduced to the minimum acceptable value, the CDX-2020 was still able to successfully track signals where there were 1.5 mm of missing data. The same held true for signals in which two successive dropouts of 1.5 mm length were "read" by the laser pickup.

Use and Listening Tests

Generally, I like to do listening tests for CD players with some of the latest discs I acquire. I have found, with few exceptions, that recently issued discs often sound better than my earlier favorites. For evaluating the Yamaha CDX2020, I chose some of Telarc's latest releases, such as their recording of Bruckner's Symphony No. 7 (CD-80188) and a two-disc set of Benjamin Britten's War Requiem (CD 80157). The latter gave me an opportunity to judge the accuracy of singing voices in three ranges (soprano, tenor, and baritone). The voices of the soloists and chorus were marvelously clear and clean, as were the softest orchestral passages. The dynamics in the Bruckner recording also came through in all their glory, with never a trace of distortion at any point in the wide-ranging and widely varying levels of sound which characterize this work.

above: Dropping the hinged panel exposes the secondary controls.

I suspect that users of this CD player will appreciate the fact that all functions are accessible from the front panel as well as the remote control. All too often, the remote for some CD player I've had connected to my system for long-term evaluation has not been readily available. If the remote is the only way I can directly access tracks (or, more often, index points), then I feel as though I am being denied some of the player's features. The Yamaha CDX-2020, by contrast, enabled me to do whatever I wanted, whether from the comfort of my listening chair or while standing up close to the front panel.

I'm still often asked whether it pays to spend more than a couple of hundred dollars on a CD player: "Aren't they all pretty much alike? Don't they all sound about the same?" I now have an excellent example to prove to these cynics that, yes indeed, some CD players are worth many times that amount, both in terms of operating features and the sound delivered. Such a player is this latest gem from Yamaha.

--Leonard Feldman

[adapted from AUDIO magazine, Dec. 1989]

Also see: Link |

Yamaha CDX-11101U CD Player (Equip. Profile, Sept. 1988)

Yamaha CD-X1 Compact Disc Player -- vintage second-generation CD player (Aug. 1984)