Peter Jurew

This is a story of how, through a marriage of acoustics and carpentry, tragedy was narrowly averted. The potential tragedy was the impending homicidal assault of one neighbor-a lover of jazz, classical, and sonically pure music-upon another, a head-banging rocker.

This story has a happy ending because, by spending about $900 and every weekend for a month, Robert Frost's aphorism, "Good fences make good neighbors," was expanded o include shared walls.

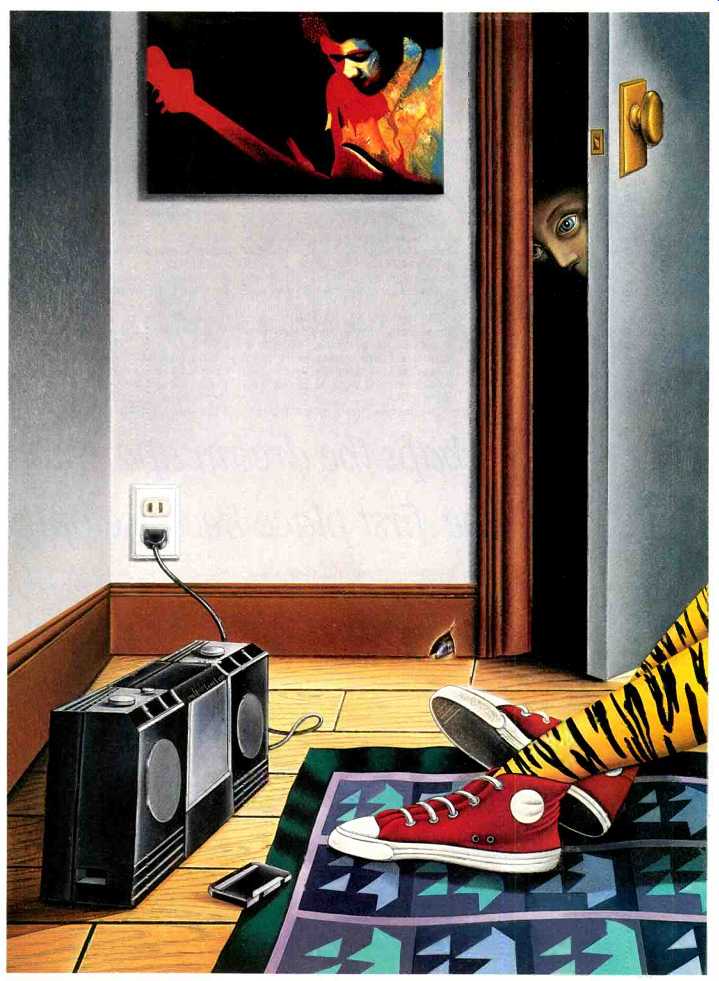

The tale begins one winter in a nearly empty apartment where two newlyweds are bedded down in sleeping bags on their first night in their first apartment together. At 8:00 a.m. the next morning, Mr. Newlywed is startled awake by the incongruous realization that someone has broken into the apartment, set up a powerful stereo, and cranked up The Grateful Dead's "Touch of Gray" as they no doubt danced around the living room.

On rising, Mr. Newlywed and his equally worried wife discover to their relief that the apartment's living room is just as barren that morning as it had been the night before.

However, the groggy couple slowly realize that they are still hearing "Touch of Gray" as if it were inside the room. Needless to say, they are extremely upset.

Searching for cracks, leaks, or holes in the wall from which the catchy tune is emanating, Mr. Newlywed finds nothing. It's a good, solid wall. He despairs at the thought of the incredible irony: They'd found a one-bedroom apartment at an affordable rent in Manhattan, and now this! The person (or persons) on the other side of the wall segues into "Disco Fever." It is 8:07 a.m. His brain spins wildly through alternatives, as though he and his wife have been trapped alive. He knows that furniture reduces echo-the moving truck is arriving today. He knows that pictures and wall hangings cut down sonic reverberation-they'll put up temporary frames, mirrors, anything. They decide that this can't go on.

Twelve hours later, Mr. and Mrs. Newlywed are sitting on their boxes, crates, and furniture, listening to their faceless friend next door unwittingly regale them with The Doors' Greatest Hits at maximum volume. "Should we say some thing?" Mrs. N asks. Taking this as his cue, Mr. N steps through the piles of belongings and makes his move.

When he gets to the door down the hall, he notices that the entire floor is echoing with his neighbor's musical over flow. He wonders if anyone else has ever said anything about the noise. He rings the doorbell, and the music goes down. A second later, clad only in leopard-print tights, the neighbor appears.

"Hi, uh,, I'm your new neighbor . . .," says Mr. N. The neighbor smiles.

"Hey, great to meet you," says Tarzan in a heavy Brooklyn accent. "I hope you don't mind the music. I like to play it loud, and the lady who lived in your apartment before you had a problem with it." "Well, I, uh, I really love The Grateful Dead. . . ." "Yeah? Seen 'em 30 or 40 times. But they're not what they used to be. Listen, you want me to turn it down, just let me know. No problem." "Gee, that's really nice of you. We love music too, but you wouldn't believe how clear your stereo sounds in our living room. In fact, we can hear everything in our bedroom, which is two rooms away." "Really? Wow, I'm sorry. I'll try to keep it down." "Hey, we'd really appreciate it.

Thanks. Oh, I have a couple great Dead tapes you might like. Fillmore East, '71?" "Got it. Great stuff, huh? Listen, take it easy. Name's Mark." The door closes. When Mr. N gets back, his wife is near tears. He immediately discovers the reason: Mark is on the phone now, his television is on, and every word is loud and clear in the newlyweds' living room. Mark is yelling

at someone on the phone; on the TV an anchorman is describing recent events. The newlyweds are petrified.

They survive the night, the week, the weekend. They decide to try to live as normally as they can. They wonder whether or not Mark was the reason their dream apartment became avail able in the first place. He is quickly driving them crazy; they are tense about coming home, expecting and receiving regular aural assaults through the living room wall. The saddest thing about the situation is that they like and even own-many of Mark's musical selections. Now these tunes are being used like weapons against them.

The breaking point comes the night they are celebrating their three-month anniversary. There is a special dinner, good wine, candles. The mood is perfect, and the newlyweds are especially happy. Then, in the middle of dinner, they hear Mark come home. They hear his door slam shut. They hear him turn his locks and flick three light switches.

They hear his stereo come on-he's dialing the radio for a station. He finds one playing Led Zeppelin. The volume goes up. Dinner is destroyed. Mr. N becomes irrational. He goes over to his trusty Marantz receiver, which puts out 100 watts per channel, pulls his speakers together, and then turns them toward the wall. On the turntable he places their one album that Mark, with his own special tastes, will likely hate-it's punk rock. Give him a very large taste of his own medicine:

Stereo war! By the middle of side one, the first stereo battle is over. Mark apparently detests punk rock as much as Mr. N thought he might. Both stereos are qui et. But Mark is on the phone. Enough for one night, Mr. N thinks, but his wife is irate. Something, she tells him, has to be done. And she's right.

The next day Mr. N makes several phone calls. One is to a friend who knows acoustics. Another call is to a friend who builds houses. He is trying to find out what solutions exist in the marketplace. He wants to buy his way out of misery.

The friends, from different backgrounds, have both suggested a floating wall. But first he's told to find out more about the source of the problem-find out what Mark's got that rocks the wall, and where it is.

That evening, the research commences. As soon as he hears Mark come home, Mr. N is at his door. Mark is surprised to see his neighbor because he hasn't even had time to turn on the stereo. Mr. N excitedly tells Mark about his plan to build a wall that will help each of them. Mark looks puzzled. But Mr. N pushes on; he just needs to see where Mark keeps his stereo so he can plan out how serious a wall he will need.

"Well, I move it around." "You what?" "I move it around. There's my box." He points to a street stereo, an AM/FM/ cassette player. Mr. N's jaw almost hits the floor.

"You make that much noise with a boombox?" "Yeah. My stereo was ripped off, and I'm down to this." "Uh, okay. Thanks a lot. But, listen, will you do me a favor and keep it away from the wall? Let's see if we can solve this thing." "Sure. No problem." The task before Mr. N seems formidable. In fact, it seems almost beyond his grasp. He's done basic carpentry, but he's never built a wall, never used sheetrock, never taped a joint. But he realizes that peace of mind, perhaps even his marriage, hinges on his success. He's got to build a wall that will keep Mark's noise out.

Construction begins the following week, when a van delivers eight 4 x 8-

foot slabs of sheetrock, forty 8-foot 2 x 3 studs, four boxes of nails, two boxes of sheetrock screws, joint tape and compound, six tubes of GE silicone caulk, 80 feet of 3-inch-wide, 1/8-inch-

thick rubber tubing, and three electrical outlet boxes. The approximate cost is $900.

The plan is this: Build two new false walls adjacent to the two existing shared walls of the two apartments effectively an "L" that will touch no single part of either of the existing

walls. By creating such a barrier, it is hoped that any aural penetration will be trapped and absorbed. The false walls will not be anchored to the existing walls in any way; they will stand free, or "float," being held in place by the combination of rubber tubing and silicone caulking where the wall meets both the floor and ceiling.

On the first day, frames are hammered together using the studs. Each false wall to be built is 20 feet long and 8 feet high. Two full 8 x 8-foot frames will be needed per false wall, and two 4 x 8-foot frames will be built to form the inside corner. By the end of the first day, the frames have been nailed together after carefully measuring each supposedly 8-foot-high ceiling. (Many ceilings are not precisely 8 feet, so cuts on the uprights will vary.) Phase II, mounting, can begin.

First, rubber tubing is rolled out along the entire length of each 20-foot existing wall, and is placed with fair precision about 2 inches out from the wall. Next, it is glued to the floor using the silicone caulk. Finally, more silicone caulk is applied to the top of the tubing, in preparation for mounting the frames.

The frames, one by one, are lifted into place and temporarily held up by jamming a wedge between the top crossbeam and the ceiling. Working down the line of top crossbeams, rubber tubing is worked into the space between the beam and ceiling, allowing one frame after another to stand on its own weight. Finally, when the entire length of one new wall frame is fixed with the rubber and the builders are confident of its strength, silicone caulk is applied to seal the gap. This amazing product, which bonds to any household material and sets like iron in hours, is the key to the project's success. It allows this new wall to be constructed 2 inches from the existing wall without a single rigid connection of any kind between them.

After the second new wall frame is similarly supported and sealed, the first phase of the project is finished. It's time to give the new wall frames a chance to settle in, give the caulk time

to set completely, and call the electrician to come and move the outlets out of the existing wall. (Crossties had al ready been cut and nailed into place between the studs closest to the out lets, in anticipation of the electrician.) While Mark's music continues to pound through their apartment, the newly weds are sleeping a little easier knowing they've at least taken matters into their own blistered hands.

The following weekend, bright and early, the electrician arrives to move the outlets. The entire operation takes about 90 minutes. It could have been done without the electrician. However, building codes make it illegal to do such operations without a professional.

Besides, it's unsafe.

At this point a dispute arises among the construction team, which has been joined by Mrs. N's father. It is a difference in soundproofing theories. One theory holds that no more insulation than the air pocket created by the new wall is necessary to effectively deaden and eliminate the sounds crashing through the old wall. The other theory is, "too much insulation ain't enough." This theory, promoted by the father-in law, calls for bringing in 6-inch fiber glass insulation, stuffing it between and behind the frames, and sealing it up with sheetrock. Under the notion that one can't be too careful, this theory wins out. Fiberglass insulation is called for, enough to run the length of a football field. No one's taking any chances.

The rest of the weekend is spent cutting the 3-foot-wide fiberglass rolls into 16-inch slices that will fit between the studs. The leftover, smaller pieces will be stuffed behind the studs to effectively blanket the entire old wall with insulation. The fiberglass installers all wear heavy work gloves to protect themselves from the glass fibers, which are painful and difficult to re move from skin. (One method is to use masking tape to lift off the glass; it works for both skin and clothing.) They also wear protective glasses and masks.

At last, they're ready to mount the sheetrock wallboards. For this purpose, a Phillips-head screw bit has been bought to employ a high-speed drill as a screw gun. The wallboards go up snugly and are quickly affixed to the frames with screws. Another theory has been modified here: It had originally been proposed (by the friend who knows acoustics) that the optimal way to mount the boards would be by using the silicone caulk only, with no screws.

But the friend who builds houses has talked the team out of that notion, saying that as long as no part of the new wall touches the old, the use of screws will have no effect whatsoever. Nevertheless, once the boards are mounted with screws, caulk is applied to seal all edges. The point is, since nobody's too sure if this thing is going to work in the first place, why not use all viable ideas? Before completing the sheetrock mounting, the team has cleverly cut out holes in the three boards that will fit over the outlets. In addition, by using a chalk line, they have located all of the studs that they will screw the boards into. And they have cut one of the boards to be used for the inside corner in such a way as to take into account the fact that the existing walls are not perfectly flush with each other. Some how, when the walls were built, the plaster warped; a slight correction has been made.

Once the sheetrock is in place, the apartment becomes transformed. And once the silicone caulk sets, an eerie silence descends over the living room.

Worried frowns come to the newly weds' faces. Is Mark out? Since the last screw has been pushed into the wallboard, they haven't heard a song or a phone conversation, not even a single flick of his wall switches. They wonder, has he moved away?

They agree that it's time for a sound check. Mr. N at last gets up the nerve to go next door and make his bizarre request.

"Hi, Mark. Uh, listen, would you mind turning your stereo up?"

Mark's probably heard stranger things in his life. But not much. He asks to what he owes this unusual fortune, for ever since the punk rock incident, he has acted distant, cornered. He obliges, however, with a singularly awful track from a long-forgotten band.

"Thanks. That sounds great. I'll be right back." With that, Mr. N returns to his own abode. His wife looks at him, confused.

"What's the matter, he's not in?" "What are you talking about? He's got it cranked . . . ." They embrace.

The newlyweds are elated over their victory. Mr. N rushes back to Mark's door, through which a gushy, string-laden disco hit can now be heard clearly.

"Thanks, Mark, you've been great. We really appreciate it." Mark seems entirely confused but is more than happy to see his normally irked neighbor looking so elated with his behavior.

So they all live happily ever after. The wall has prevailed even when warm weather brings open windows. And as it ages, it seems to become more and more a symbol of rational behavior-even if that doesn't sound like a whole lot of fun.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Dec. 1990)

Also see:

Muffling the Neighbors: Ten Tips to Reduce Noise (Nov. 1990)

Earning a Deaf Ear: Loud Music & Hearing Loss (Jan. 1989)

= = = =