Just a few months before the first issue of Audio magazine (1947-2000) rolled off the presses (dated May 1947 and then called Audio Engineering), the trend-spotters at Fortune homed in on a little-understood hobbyist preoccupation. High fidelity wouldn't become a household term for several years, but Fortune's extensive coverage of the phenomenon--the text, photos, illustrations, and charts took up 11 pages in its October 1946 issue--was a shot heard round the world. "That article was the watershed for our company internationally," remarked Avery Fisher, whose Fisher radio phonographs won first-place rankings. Some four decades later, this founding father recalled the torrent of orders that flowed in from people who "literally [constituted] a Who's Who of American industry, education, and government."

High fidelity was a post-World War II hybrid, in large part propagated by Americans, and the sonic shoots that sprouted from new ground had deep roots. These reached back in several directions to broadcasting, recording, motion pictures, telecommunications, and even submarine detection. Fisher himself had become an electronics manufacturer shortly before American factories turned their efforts to military work. Head quartered in a 750-square-foot office and manufacturing space, part of a shared loft on Manhattan's West 21st Street, he was then assembling tuned radio-frequency receivers under the Philharmonic brand name. "The object was to get the best possible reproduction of local stations and the best possible reproduction of recordings," he later explained.

ABOVE: The demure woman on the cover of the May 1951 issue seems unruffled

by the monster multi-horn speaker in her living room.

ABOVE: Avery Fisher tested each of his components, like this early stereo

Model 400 Master Audio Control tube preamp, at home.

=======

FM and the LP

Edwin Howard Armstrong's idea of modulating the frequency of radio waves (FM), rather than their amplitude (AM), had numerous advantages, including substantially lower noise. RCA chief David Sarnoff had been an early supporter, but he soon turned his back on the inventor, so Arm strong resolved to finance FM radio from the substantial funds his earlier inventions--the regenerative, super-heterodyne, and super-regenerative radio circuits--had earned. On July 1 8, 1 939, he began broad casting from his own station, W2XMN, in Alpine, New Jersey. Although FM provided program material that helped hi-fi succeed, it became Armstrong's nemesis. Entangled in a web of patent lawsuits, on January 31, 1954, he hurled himself from a 10th-floor window. His widow, Marion MacInnis Armstrong, whom he had met when she was working as Sarnoff's secretary, pursued the litigation that continued for another 13 years and ultimately won.

The long-playing record was an even more significant program source for hi-fi listeners. Developed by Peter Goldmark and colleagues toiling in the electronic vineyard at CBS Laboratories, the LP combined vinyl for quieter surfaces with a narrowed groove and a reduced playing speed. Officially introduced by Columbia in 1947, it remained the reference standard for nearly 40 years.

ABOVE: Peter Goldmark's development of the LP record, at CBS Labs in

1947, was a catalyst to the fledgling audio industry.

==========

HORN SECTION

When, in the mid-1980s, numerous hi-fi makers began calling their products "digital-ready," one Audio reviewer commented that the only really digital-ready speaker was one Paul Klipsch had devised some four decades earlier in Hope, Arkansas. (Prior to that, the area's best-known invention had been the Bowie knife.) To scale the cabinet down, Klipsch folded a horn into segments connected by acute angles and split it into two lengthwise sections that re joined at the mouth. The result was the Klipschorn, which remains in the Klipsch line to this day.

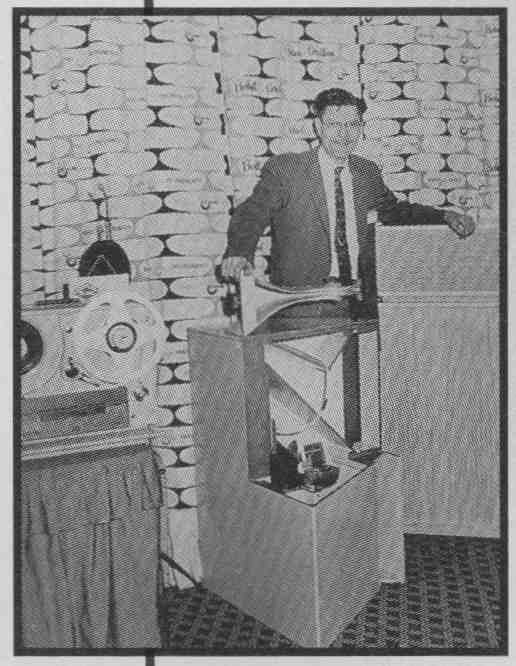

ABOVE: Paul Klipsch's folded-horn speaker, the Klipschorn, could produce

deafening sound levels from low-powered '50s amplifiers.

========

The Maestro: Sidney Harman

One of the men who helped get hi-fi out of the bock corners of radio parts stores is operating at higher volume than ever. Not long after Sidney Harman founded Harman Kardon in 1952, the company introduced the Festival D1000, the first commercially available hi-fi receiver. Harman went on to earn a do in organizational and social psychology, later both espousing and creating innovative programs to enhance quality of life in the workplace. He served for three years as president of Friends World College, a worldwide experimental Quaker institution, and has been a Deputy Secretary in the U.S. Department of Commerce. Today, as chairman and CEO of Harman International, the hi-fi pioneer presides over an audio empire that includes JBL, Infinity, Harmon Kardon, Madrigal (which produces Mark Levinson and Proceed components), AKG, Lexicon, Revel, Studer, dbx, and other companies. Sales for fiscal 1996 were $1.36 billion.

Among the earliest stereo receivers, this Harman Kardon Festival model had duplicate controls for each channel and separate dials for FM and AM tuning.

Sidney Harman, co-founder of Harman Kardon, brought his marketing genius to the audio industry. Harman International now owns JBL, Infinity, Madrigal, Harman Kardon, Lexicon, AKG, Studer, and others.

=========

Fisher, in his own words, was a "meticulous hobbyist who wanted to get the best results," and there were others like him. In its far-reaching 1946 report on hi-fi , Fortune profiled one such man, New York radio engineer Thomas R. Kennedy, Jr., "whose avocation is fine music well performed. A 'golden ear' of the richest sheen, he is one of that small band who have dedicated a good part of their lives to extending the range of reproduced sounds to the limits of human hearing," the writer explained. "Merely reproducing the highs and lows to which most prewar instruments are deaf will not satisfy Tom Kennedy or any other golden ear. A purist, he insists that the tones be noise-free and undistorted, sharp, clear, and full from treble to bass. The only damper his enthusiasm seems to know-so far not very effective-is the fact that when fidelity even approaches the degree achieved in his laboratory, the cost graph rises like a helicopter." The Fortune story went on to document the "fantastic lengths" to which Kennedy had gone in assembling his system, which, "of course, [ an FM circuit" as well as an amplifier "built at the Bell Telephone Laboratories." The speaker comprised "three units"; the record player, "to forestall phonograph vibration," employed a separate motor connected with "a dental-machine belt" to a turntable embedded in 600 pounds of sand. "The pickup arm sports a feather-light sapphire needle kept at even temperature and humidity in an airtight container until just before it is used," the Fortune writer continued. Not surprisingly, Kennedy was sometimes accused of "making a fetish" of his hobby, but he challenged detractors to compare "music from my equipment with what the aver age combination gives. You'll go home and throw rocks at your set," he boasted.

Funeral March

There was, however, a tarnished side to this glittering coin, and Fortune, which had begun its hi-fi story by noting that the American public "is getting a poor deal to day in the line of musical reproduction," was not shy about laying blame. The report fingered major manufacturers with "standards of fidelity. . .years behind practicable levels." Given "heavy investments in plants, patents, and franchises," these companies were said to find high fidelity a threat.

"Cagily," the publication observed, "they have moved out of the defensive position with an attack," contending that "the public neither wants nor likes wide-range reception or wide- range instruments." The big corporations had evidence of this. Fortune cited a test by two Columbia Broadcasting System staffers that found "audiences chose standard broadcasts (up to 5,000 cycles) over wide-range programs (up to 10,000) by more than two to one." Moreover, FM radio owners, "presumably with highly developed tastes," voted more than four to one for limited band width while professional musicians came down "against wide ranges and thus, apparently, against high fidelity" by a mar gin of 15 to one. While there are many possible reasons for this, a comment by Rudy Bozak, one of hi-fi 's first major speaker designers, may explain it best.

"The ear is a very queer thing," Bozak observed. "Our reaction to what we hear is subject to a number of things, not the least of which is our disposition of the moment. You know, I built my first radio set in 1922, and my loudspeaker system was a soup plate with a pair of earphones put in it. We were tremendously impressed about how great the thing was because, in that particular instance, the novelty matched every thing else. It's only after continued hearing or association that people begin to be critical. . . .The ear educates itself in time." For many years, the small firms that constituted the fledgling high-fidelity industry lived in fear of the manufacturing giants, even as the big companies continued to pursue resolutely no-fi marketing strategies. Had they reversed their course and marched upmarket, they may well have crushed the newcomers under their boot heels, but corporate commanders kept their division-strength columns moving straight ahead.

ABOVE: In May 1947, the cover of this man showed Norman Pickering testing

his innovative new phono cartridge.

=======

The Upper Resister

ABOVE: When McIntosh abandoned industrial gray paint for chrome chassis

and enclosed, black enamel transformer cans, sales of its power amps took off.

Frank McIntosh introduced his company's first product, the Model 50 W amplifier, in 1949. The 50-watt design was the first to keep distortion under 1% from 20 Hz to 20 kHz. It was develop from McIntosh's concept by Gordon Gow (who relinquished the patent right to McIntosh and was made a vice pre dent of the company, which he later to over and ran for many years). The 50 W was used primarily for studio and sound reinforcement applications, but a significant number of hi-fi cognoscenti we willing to pay $249.50 for it. The company made even deeper inroads into the consumer market in the mid-1950s when it substituted chrome chassis and enclosed, black enamel transformer ca for the industrial gray paint that previous products had worn. McIntosh's primary marketing tool, however, was its engineering philosophy: Build the best products possible, and build them last. A traveling clinic program w countless friends as well. McIntosh tested any amp carried into its dealer’s showrooms on specified days and compared the specs to those of its own units. The program began in 1962, and, by time it was discontinued 29 years later, more than 300,000 amplifiers had been tested.

========

Perpetuum Mobile

With a bewildering array of products crowding store shelves, it's hard today for Americans to envision a nation as starved for consumer goods as this one was in the mid-1940s. Jack Fields, for years a New York-area sales representative wholesaling various hi-fi brands, was able to shed light on that era. Shortly before the War ended, Fields related to a group of industry colleagues some time ago, "Webcor got a contract from the Navy to build 400 record changers for recreational purposes." The government had paid for the tooling, he explained, and when the War ended, the company was "prepared to produce, literally, thousands of changers." Fields went down to lower Manhattan's Cortlandt Street, which was lined with a row of radio parts stores. (Along with their counterparts on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles and in other American cities, they were to become the first outlets for early audio component manufacturers.) Fields had thought he'd sell "maybe 100 record changers," but by the end of the day he had written orders for 6,000.

The sales rep then learned, much to his dismay, that Webcor had reserved all but a few hundred units a month for console manufacturers. These companies found themselves unable to procure enough cabinets to house their allocation, however, so Webcor shipped to the Cortlandt Street dealers, and Fields was on hand the day the first cartons arrived. "I'll never forget it," he marveled, "because I never knew what 500 record changers looked like. The entire sidewalk was blocked off about 10 feet high. Everybody was loading them in, and they were selling them as fast as they could get them." Avery Fisher held a dim opinion of Cortlandt Street, which he called Swindle Street. An early experience there preceded his interest in the kind of sound that would be come known as high fidelity. He had gone downtown, he recounted, to buy a radio as a gift for his parents, whose East 94th Street apartment then had DC current. His choice came down to two models, one with six tubes and one with eight. Because "Fisher always went for quality," he opted for the eight-tube set. Some years later, when he took the radio in for service, he found that the two additional tubes "were not even in a circuit; all they did was light up." Nor did the hi-fi pioneer ever forget the Cortlandt Street merchant who specialized in used tubes and displayed a sign that stated, "Our tubes are guaranteed for life." That meant the life of the tube and, Fisher suggested ruefully, was not meant to be humorous.

Saul Marantz was just one of the young men who, after the War ended, went to electronics stores seeking parts and information. Recently discharged from the Merchant Marines, he had tried to install a car radio in his living room. "It didn't work," he noted many years afterward. "I found I had to have a 6-volt power supply. And I had to get rid of my loudspeaker because it had an electromagnetic field coil. I went down to Harvey Radio [in New York City] and asked some questions. I didn't know much about it in those days." He seems to have learned quickly. The company he later founded produced such legendary components as the Model 7 preamp, the 8B and 9 amplifiers, and the 10B tuner; today, these are valuable collector's items.

ABOVE: Many audiophiles coveted this high-end Marantz Model 150 stereo tuner

with its built-in oscilloscope display.

ABOVE: Classic '50s high end: The Marantz Model 9 tube power amplifier had adjustable

bias, DC balance, and AC balance.

ABOVE: The appearance of bookshelf speakers (top shelf), record changers,

and integrated electronics helped popularize audio in the mid-'60s. Visible

in the lower foreground are a marble-topped Empire Grenadier speaker and Bose's

first speaker, the multidriver 2201.

===========

Build It Yourself

No one will ever know just how many hi-fi aficionados cut their teeth on kits. Eico and Heath were two popular early names, but, thanks to David Hafler, Dynaco's dynamo, that name stands out. For one thing, by relegating much of the critical wiring to the factory, Hafler made sure that buyers could assemble Dynakits quickly, often in a small fraction of the time it took to put together competing products. While Hafler insisted on good sound, he also made sure his engineering staff adhered to simple design principles. This resulted in true value for every dollar that listeners allotted to Dynakit components, and later to the company's wired gear.

ABOVE: David Hafler's Dynakit Mark II amplifier could be assembled in two hours.

The 60-watt amp cost $79.95 in 1957.

ABOVE: Low-cost easy-to-build hi-fi kits, like Heathkit EA-2 14-watt mono tube

integrated amp were popular in the late '50s. See more Heathkit at: heathkit-museum.com

==========

Virtuoso Duet

Consumer hi-fi exhibitions were ideal showcases for products in a relatively obscure field. The first, the 1949 New York Audio Fair, was officially sponsored by the Audio Engineering Society but planned by this magazine and produced by its sales manager, Harry Reizes. The then-annual event at the Hotel New Yorker engendered shows in Chicago in 1952 and in Los Angeles the following year. In 1954, Japan imported the concept; the reported attendance figure, 55,000, was an early indication of what would become a nearly insatiable national appetite for high-fidelity components.

At just about the time Reizes was writing the libretto for the 1949 Audio Fair, Rudy Bozak was on the road peddling his first loudspeaker. Previously employed by Milwaukee's Allen-Bradley Company, Cinaudagraph, and instrument makers C. G. Conn and Wurlitzer, Bozak was about to turn 40 and was finally in business for himself. But even though he "made a tour from Buffalo to Boston, down the coast to New York and Philadelphia," the trip resulted in only a single sale.

Then an opportunity arose for Bozak to put his speaker in an appropriate setting for a component that was housed in a kettle drum. "I didn't buy any space at the show from Harry, but they had a loudspeaker comparison on stage in the ballroom, and we were invited to participate," he recalled in the last interview before his death in 1982 (Audio, May 1982). "We put our 201 there, and it stood up with the best in the business at that time. There was Klipsch, Altec's 604, JBL, the names that prevailed at that time, and we made a definite impression.

ABOVE--In the early 60s the AR turntable popularized the use of a floppy platter/tonearm

sub-suspension which greatly reduced rumble and acoustic feedback. See more

turntable history at: vinylnirvana.com

ABOVE--The Bozak Symphony No.1 B-4000A was a big, floor-standing speaker with

eight tweeters, a midrange driver, and two woofers.

=======

Riding on Air

Edgar Vilichur's acoustic-suspension speaker substituted the air in a relatively small, sealed box for the mechanical suspensions that previously helped control driver motion. Though he had to Form a company, Acoustic Research, to get the design into production, the AR-i went on to revolutionize the loudspeaker industry after its 1 954 debut. Henry Kloss, an AR co-founder, endowed the venture with a small Cambridge, Massachusetts, manufacturing facility in which he had been building cabinets for the Baruch-Lang loudspeaker, one of hi-fi's earliest models. Kloss also brought along two friends, Malcolm Low and J. Anton Hoffmann (son of the legendary piano virtuoso Josef Hofmann). After about three years Kloss Low and Hofmann sold their interest in AR to Vilichur and founded KLH Kloss subsequently went on to other startups including Advent Kloss Video and Cambridge SoundWorks

ABOVE--The bookshelf sized AR-1 speaker produced usable response to below

30 hz.

ABOVE--The KLH Model Eleven, designed by Henry Kloss, was audio's first

portable stereo hi-fi. The acoustic-suspension speakers folded into the ends

of a suitcase housing a record changer and a solid-state amp.

=======

"The thing that really made Bozak," the speaker designer emphasized, was his friendship with the record producer Emory Cook, "an idealist in recording. The fact that I was an idealist in loudspeakers made for a mutual meshing of feeling," Bozak remarked.

"Emory liked to dramatize things, very much so.

He came to me and said, 'Rudy, we want to steal the show at the 1951 Audio Fair. I'll make some recordings and you give me a loudspeaker with good bass and good highs, and we'll put this show on.' "Cook had just the record to do it, Rail Dynamics, a recording of trains that he had made, mainly at night, in yards at Harmon and Peekskill, north of New York City. (Cook subsequently noted that " Peekskill is a mountainous area, very nice for acoustics"; the sound, he said, would bounce across the Hudson River and then back again.) "We just stole the show," Bozak smiled. "The comments! Down the corridors, from around the corners, people would say, 'Where are those railroad trains?'"

ABOVE-- Emory Cook's demo LP recording of steam locomotives, Rail Dynamics, wowed attendees at the 1951 Audio Fair ill New York.

ABOVE--54 In the 1950s, Emory Cook made the first stereo field recording of

trains and pipe organs, which audiophiles used to show off their hi-fi systems.

ABOVE-- Avery Robert Fisher 1906-1994),

an ardent amateur violinist, donated $12 million to New York's Lincoln Center

for the Performing Arts when he sold his company.

It would have been difficult for some to follow that act, but not for Bozak and Cook. At the 1952 Audio Fair, Emory Cook turned up with a stereo record. His system, which he called binaural, divided the disc into two separate bands of grooves, one with left-channel and the other with right-channel information. To play his records, he took along a bifurcated tonearm with twin pickups.

For their next attraction, this dynamic duo provided Audio Fair attendees with truly amazing bass. In 1952, Cook began making recordings of organist Reginald Foort, who had been a popular figure in England during the War. At a session in Boston's Symphony Hall, the producer told Foort that he was going to record him playing at 16 cycles. Recording a tone that low was unprecedented, and the organist said it could not be done. "I said, 'Do it anyway,' so he did," Cook recalled nearly 40 years after ward (Audio, September 1989). "He was co operative enough to do that."

To reproduce organ tones down to 16 Hz, Bozak built a special pair of speakers, each of which had two cabinets. The lower housing contained eight 12-inch woofers and measured 4 feet wide, 5 feet high, and 21 inches deep. (A larger woofer complement would have required a box so large that it wouldn't fit through a hotel-room door.) The second enclosure held two 6- inch midrange drivers and a tweeter cluster. A visitor who had heard these speakers at the Hotel New Yorker later remembered feeling his trouser legs flap. Cook himself recalled that, when he played his organ recording, "The pedal frequencies were heard in the lobby sometimes-felt was more like it. It's not something you could resolve and say, 'Oh, that's an organ' or whatever, but it's strange how sound would travel around the hotel and up and down the elevator shafts then come out in the lobby. A feeling--not music, a feeling. . . .And it wasn't loud in the room. [ speakers] were played only somewhat louder than you would play them in your own living room." Some of hi-fi 's groundbreaking manufacturers, Rudy Bozak and Emory Cook included, held engineer's credentials, but others, like Saul Marantz and Avery Fisher, substituted hobbyist zeal for formal technical training. Fisher had two brothers who were engineers, but his own background was artistic; he had been a prize-winning book designer at Dodd, Mead and Company and was an ardent amateur violinist. Joseph Tushinsky, who did much to establish Sony on these shores, was also a musician and, while still in high school, worked as a professional trumpeter. In 1942, when lack of air conditioning led officials at New York's Carnegie Hall to lease the facility in summer, Tushinsky produced a light opera festival there and conducted every performance.

The following year, with his younger brother Irving, Tushinsky migrated to Southern California to work in the film industry. When 3-D movies became a fad in the early '50s, the pair began searching for a process that would eliminate the cumbersome glasses the medium required. As Joe Tushinsky later recounted, they were faring rather poorly when Irving devised a dual- prism widescreen process that seemed promising. The Tushinskys, who were working at the RKO studios at the time, formed a company to produce the lens and, at the suggestion of Howard Hughes, named it Superscope.

In 1957, Far East Film Laboratories invited the Tushinskys to Japan to install their system. Fantasia had just been rereleased in their process, and "the name Superscope was blazoned all over Tokyo," the elder brother recalled. This put the men in a favor able light when they visited Sony headquarters, where they spotted seven tape recorders that they learned were the world's first stereo models to have inboard amplification.

In true Hollywood fashion, Joe Tushinsky pulled a sheaf of yen from his pocket (he had received a plane-fare reimbursement in Japanese currency, but government regulations required that he spend most of it before leaving the country) and brashly offered to buy all seven machines. He told his hosts he'd show them in America, where they might prove salable. (He later confessed that he wanted to get them out of sight until he concluded a deal to become the U.S. importer.) Tushinsky got six of the tape recorders, and he closed the deal. A few years later, in the early '60s, Superscope acquired Marantz from its founder and began producing equipment under that venerable name.

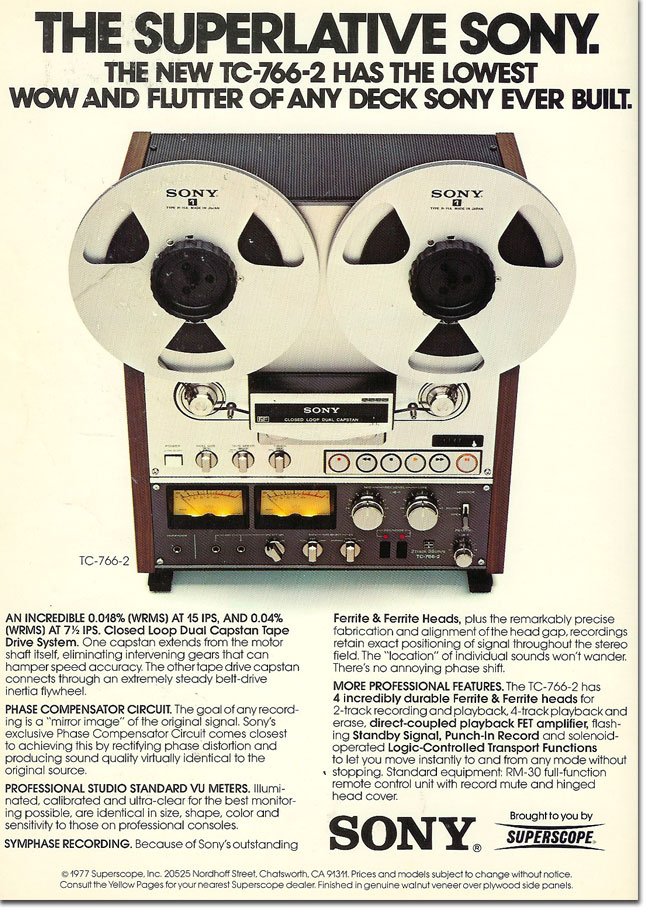

ABOVE--When Joe Tushinsky got a deal in 1957 to distribute Sony open reel stereo

recorders in America, he used the name Superscope which had used for a 3D movie

process.

Coda

A. Whitney Griswold, a former English professor and Yale University president who died in the early 1960s, once rhetorically asked if Hamlet could have been written by a committee. He could have been making a point about the high-fidelity industry. Almost without exception, individuals-not corporations-created hi-fi, and they were highly passionate about their products.

In an interview (Audio magazine, September 1990) conducted in the Park Avenue apartment where he lived for many years, I asked Avery Fisher if he had ever considered lowering the quality of his equipment in order to appeal to a larger market. "It never entered my mind," he replied, "because I had no personal interest in it. No model we ever turned out was brought anywhere near production before prototypes were brought into this home, this room as a matter of fact, and lived with for a while." In 1973, Fisher donated $12 million (more than a third of the $31 million he had received when he sold his company a few years earlier) to New York's Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. As a result, one of the city's two principal concert halls now carries his name. Other first- and second-generation hi-fi names continue to grace today's equipment; they pay homage to the talents of men named Bose, Bozak, Grado, Harman, Kardon, Klipsch, Koss, Marantz, McIntosh, and Shure. Still other names associated with the nascent hi-fi industry-some little known, some as recognizable as that of H. H. Scott-have faded into silence. But even after most or all disappear into anonymity, music lovers will owe a debt to those who cultivated the high-fidelity garden in its earliest years. At times, the soil must have seemed less than fertile.

Adapted from Audio magazine (1947-2000). Classic Audio and Audio Engineering magazine issues are available for free download at the Internet Archive (archive.org, aka The Wayback Machine)

Also see:

Audio Milestones: The March of Technology: Years and Years of Record Playing (May 1997)