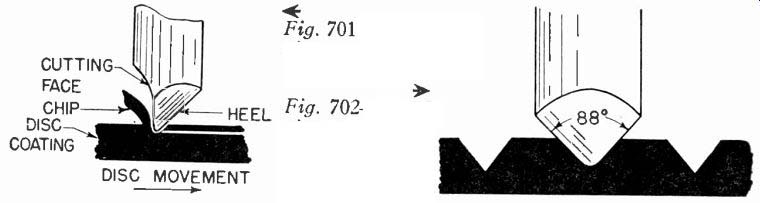

THE stylus is another highly important link in the recording chain. It is a specially shaped, precision ground and lapped tool. Fig. 701 shows a side view of the stylus tip. Note that the cutting face of the stylus is flat, while the heel makes an angle of about 60 degrees with the cutting face. Fig. 702 shows a front view of the tip, with the observer looking directly at the cutting face. Notice that the bottom is not a perfect point (except in a steel stylus) but is very slightly and symmetrically rounded. The radius of the tip is about .0022 inch. The angle of the V, approximately 88 degrees, is known as the included angle.

Fig. 701--Side view of stylus tip.

Fig. 702--Front view of the tip and cutting face, showing included angle.

Fig. 702 shows 2 important facts : first, that the shape of the groove is the same as the stylus cutting face ; and second, that the entire cutting face is not used. Fig. 702 shows that as the stylus cuts a deeper groove it cuts a wider groove. This bears directly on the matter of cutting pitch or number of lines per inch.

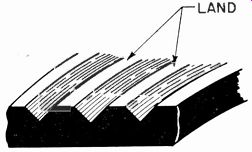

Fig. 703--Several adjacent grooves, showing "land" between

grooves.

Fig. 703 shows several adjacent grooves. If the pitch remains constant and the grooves are cut deeper and therefore wider, the land separating the grooves becomes too narrow or disappears. The pickup then jumps grooves or becomes stuck in one groove and produces the familiar "broken record" effect of repetition. If stylus movement in one groove causes the walls of adjacent grooves to assume somewhat the same shape as the groove being cut, there will be an "echo." Because the playback needle traveling in any groove will reproduce, not only the sound recorded in that groove, but also (at a lower level) some of the sound in adjacent grooves, the name echo is appropriate.

In practice, weight on the stylus is adjusted so that the depth of cut is between .0015 and .0025 inch for all pitches. Instructions for making this adjustment are given in Section 10.

Fig. 704--Stylus cutting face must be perpendicular during recording.

During recording, the cutting face of the stylus must be absolutely vertical.

Fig. 704 shows that a stylus in the wrong position will dig into the disc surface and tear the material rather than engraving, or will glide over the surface. This adjustment is also described in Section 10.

An irregularity in the stylus tip will affect the shape of the cut groove.

Raggedness, caused by wear, will tear the record coating. Any stylus imperfection results in an increase in surface noise and a dull rather than a shiny cut.

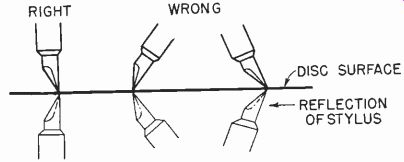

Styli are made principally of 3 materials.

The least expensive initially is the steel stylus (Fig. 705), made from a single piece of metal.

The upper portion of the shank is flat on the side opposite the cutting face.

When the stylus is inserted into the chuck of the cutter, the setscrew hits the flatted portion and automatically places the cutting face in the proper position.

Steel has at least two disadvantages. The first is a comparative softness. As it engraves, the frictional heat produced at the tip quickly dulls it and small ragged irregularities appear, which make the stylus worthless for further use. As a matter of fact, even the minute irregularities in the surface-for steel cannot be polished to a high degree of smoothness-make a noisy cut unavoidable.

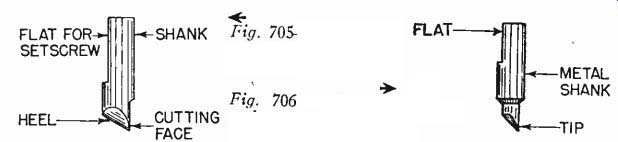

Fig. 705-Steel stylus--note heel and cutting face. Fig. 706--Sapphire stylus,

mounted in hard metal shank.

And since steel is flexible, at higher frequencies, the stylus, instead of conforming stiffly to the armature movements, sways and bends slightly. The cut groove does riot vary its path as much as armature movement warrants and there is less response in the high-frequency range. The steel stylus is priced under 50¢, but cannot be used for more than 30 minutes of recording.

The sapphire (natural or synthetic), acknowledged the best material for recording, is almost as hard as diamond and can be polished to an almost unbelievable degree of smoothness. Fig. 706 shows a sapphire stylus. It consists of a sapphire tip mounted in a shank of hard metal. at higher frequencies, the stylus, instead of conforming stiffly to the armature movements, sways and bends slightly. The cut groove does riot vary its path as much as armature movement warrants and there is less response in the high-frequency range. The steel stylus is priced under 50¢, but cannot be used for more than 30 minutes of recording.

The sapphire (natural or synthetic), acknowledged the best material for recording, is almost as hard as diamond and can be polished to an almost unbelievable degree of smoothness. Fig. 706 shows a sapphire stylus. It consists of a sapphire tip mounted in a shank of hard metal.

The assembly is extremely stiff, and, when good discs are used, frequencies up to 10,000 cycles can be recorded without perceptible attenuation caused by stylus flexibility.

Sapphire is especially valuable because its smooth edges polish the groove as they cut and the groove becomes extremely smooth and very quiet.

Sapphire styli are originally several times more expensive than steel ones. However, unlike the steel, sapphires can be re-sharpened at comparatively small cost and will give as good service as new ones.

Generally, if the worn stylus is taken to the distributor, a new or sharpened one will be supplied for a moderate resharpening charge in ex change for the worn unit.

Sapphire styli are economical for recording as little as 3 or 4 hours monthly, since the original cost plus occasional sharpening charges add up to less than the price of a new steel tool every half hour or less. Under proper conditions of adjustment, a sapphire will cut for several hours before it must be re-sharpened.

Sapphire is brittle, and a chipped stylus is a total loss. Therefore, take every precaution to see that a sapphire stylus is not dropped or hit against anything. When it is not in use, treat it with care. Usually a small plastic tube is furnished with each stylus, which will contain it safely. During recording, lower the stylus very gently onto the rotating record surface. Do not start the turntable with the stylus resting on the disc! The stellite stylus is more economical than one of sapphire. Stellite, a metallic alloy which gives cutting characteristics almost as good as sapphire, lasts much longer than steel but not as long as sapphire. However, original cost and resharpening charges are less. Stellite tips are mounted the same as sapphires.

To determine whether a sapphire or stellite stylus needs resharpening, cut a few grooves with the stylus. Using a single light source, hold the disc so that the light is obliquely reflected to the eye. If the grooves are shiny, all is well. If they are dull, re-sharpen the stylus.