Rx for RF Interference

by William Warriner

If your stereo system picks up signals it shouldn't, there may be simple ways of eliminating them.

EVERY SECOND of our lives, we are bombarded by wave energy. We swim in it, half consciously, like fish in the ocean. Its gross currents--which are variations in atmospheric pressure--come to us as sound, and human ears can get a reading on a good portion of its spectrum. But electromagnetic energy is something else. We are equipped to detect some of its wave activity with skin (check your sunburn) and with the eyes. Yet the known electromagnetic spectrum from direct current through light to cosmic rays contains 60 octaves, and our eyes respond to but one octave at around 10^15 (1 quadrillion) hertz. Clearly there is a lot going on that we don't know about.

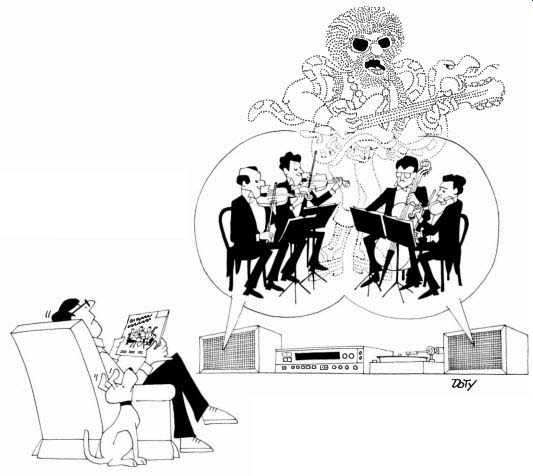

Broadcast energy-people making waves, so to speak-is a powerful current in our neighborhood of the ocean. Of course it has a job to do and does it, but sometimes it also lets us hear peculiar things: disembodied voices, strange whistles, heavenly music-and when heavenly music has a commercial tagging along, we naturally be come suspicious about its provenance. The cur rent has swept us into the little--charted sea called radio frequency interference, or RFI in the text books. The following are some scenarios of confrontations with its terrors.

First scenario: You are sitting in your living room trying to hear. broadcast information (a string quartet), and another signal source (an automobile ignition system) expresses itself through your loudspeaker. We call that noise since we don't like it, but this is an arbitrary definition.

(Dandelions may be weeds to you; to Euell Gibbons they were food.) The automobile can't work without those pulses. The tuner doesn't understand the difference and is just obeying orders.

In scenario No. 2, the original broadcast energy itself is defined as noise when it trespasses upon the wrong circuits. They may or may not be audio circuits. For example, a few years back, an Air Force radar installation near Willingboro, New Jersey, lowered its sights from satellite tracking to look for sea-launched ballistic missiles and was immediately accused of interfering with local radio, television, stereo sets, hearing aids--and heart pacemakers.

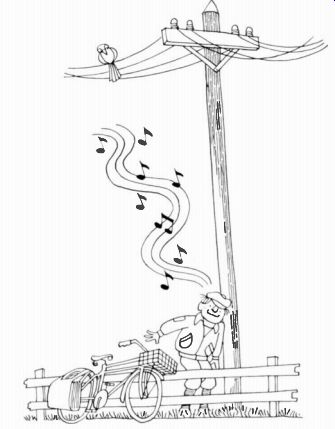

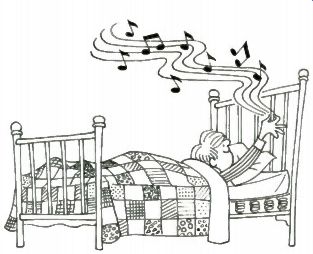

Scenario No. 3, the spookiest, can make you want to take up Eastern philosophy in your spare time. Broadcast information can turn up in places where it is not only unwanted, but unlikely, and not as inarticulate noise, but as a fully translated audio program--maybe a string quartet, but more likely Elton John. Frederic B. Jeuneman, a scientist writing in Industrial Research magazine for October 1971, told this tale: "When he was a boy, a friend of mine lay on his iron bedstead and upon touching the frame heard a local radio station. His parents, not believing the story, had no interest in observing the phenomenon." I was happy to read that from a proper authority, because when I was a kid nobody believed my story either. I was befriended by a musical tele phone pole. It had a big old transformer on top, and it was located along my morning newspaper route on New York State Highway 7, a good half mile from any human habitation. When I parked my bike and climbed over the guardrail and stood up close, I could hear an FM station from Binghamton, fifteen miles away.

The explanation of these phenomena can be quick and almost painless. The components of a simple AM radio receiver are common enough: a detector followed by an amplifier, followed by a transducer. Start with the fact that any diode can serve as a detector, passing an alternating current in one direction only and so rectifying it. A poor electrical connection can behave as an imperfect diode, and some rectification may occur at the junction. The rest, frequently, is a matter of resonance. If coupling exists with any vibrating body, there is your potential transducer. If the RF signal is strong enough, amplification may be unnecessary. A child touching a bed can serve as an antenna or may tune the welded seams of his strange receiver. A telephone pole has miles of wire acting as an antenna to pick up the initial RF: its transformer coil generates a magnetic field, which conceivably could be modulated to produce mechanical vibrations at audio frequencies in the metal casing. If you are so inclined, you can spend a free evening or more cataloguing the combinations that can add up to accidental radio.

The point is that it is naive to think that the components of a radio receiver occur only when assembled willfully and with intent to receive.

Thinking that radio comes only from tuners is like a city kid thinking that milk comes only from plastic cartons. People have picked up radio programs with the fillings in their teeth. I know of a Boston recording studio that had to rebuild its entire mixing console because audio from a nearby FM rock station showed up in everything it put on tape. An elaborate PA system, moved from a past Newport Jazz Festival to the ballroom of a Miami hotel, not only reproduced the tape-recorded music it was supposed to play, but included sotto voce the continuous patter of a disc jockey working half a mile away. In the Toronto CBC studio where he creates his radio productions, Glenn Gould had to have ...

... every piece of audio equipment "debugged." Any audio engineer will have his own RFI war stories to tell.

Of course the same thing can happen in your home audio installation, where it is no fun at all, and exorcising the spurious voices can be a lot of trouble. There are three ways to deal with RFI. You can try social action, you can putter around with your installation, or you can construct corrective circuitry. This last approach is beyond the scope of this article, but a lot can still be done with the first two.

Social Action. If your RFI is from a ham radio operator, listen for his call letters and use them to get his name and phone number from the Federal Communications Commission. Call him. Be friendly. Explain your problem. He has taken an oath to be nice. He should be able to share his knowledge of electronics to help solve the problem and may even be willing to look at your setup and lend a hand.

If your RFI is from a commercial radio station, you may get some help from its chief engineer.

Some chief engineers are harassed and crotchety.

Others are downright talkative and full of good ideas. It's worth a phone call to find out.

Except for rare cases of unlicensed or just plain sloppy operation, the offending transmitter is approved by the FCC, and nothing is going to change that fact, so RFI has to be corrected in your own equipment, not in the transmitter. Some high fidelity components are more thoughtfully designed than others, and two amplifiers (or turntables, etc.) of otherwise equal quality may differ in RFI susceptibility. If you live near a broadcast tower (or a ham or a taxi dispatcher), this is something to think about before you make a decision to buy equipment.

Puttering. Frequently RFI can be eliminated by making minor changes in wiring or even by rear ranging a high fidelity installation. RFI is such a skittish thing that almost anything you do will work sometimes. But as with any ghost, there is no one thing that will work every time.

Here is what will almost always not work: (1) Turning the AC plug around (except on rare occasions with very cheap amps that have no input power transformer). (2) Moving parallel wires so they are no longer parallel (if your wiring is the main culprit, they are acting as an antenna-and length is a bigger factor than position). (3) Cleaning, dusting, and lubricating plugs and other contact points (usually these actions won't affect the physical gap in which rectification is taking place). It seems that RFI often eludes pure logic, so the rational procedure is to take the simplest corrective actions first.

CUT LEADS. Begin by turning the preamp volume control (or whatever volume controls are avail able) down to zero. If the level of the unwanted program is unaffected, you can usually assume that the RFI is entering after that point in your sys tem. There is a good chance that it is at the output end of the amplifier. Since virtually all high fidelity amplifiers have feedback from the output stage, the speaker leads can act as an antenna, feeding the signal in at the output. One simple course of action is to shorten or lengthen the speaker wires a few inches at a time and look for improvement. If the wires are acting as a resonant antenna, altering the length should detune the circuit. But don't go too far--you may simply establish a new resonance.

TIGHTEN CONTACTS. This measure, next in order of simplicity, can be accomplished with the teeth- but a pair of pliers is better. Remembering that rectification often occurs at a poor contact point (a pseudo-diode), approach the phono plugs (RCA plugs) in your installation one at a time and com press the ground tabs so they will make tighter contact.

REARRANGE COMPONENTS. In theory, you can localize the RFI rectification point to a particular component-preamp, phono cartridge, etc.-by un plugging each piece of equipment, exclusive of amplifier and speakers, one at a time. Do so with the volume at zero. If the RFI disappears when you unplug the turntable, you may think you have isolated it in the turntable or phono cartridge, but this may not be true.

You can test the first hypothesis (rectification in the phono cartridge) by tightening the contacts on the cartridge output leads, or by substituting another turntable, or another cartridge. But these measures are becoming complicated, so the Rule of Simplicity leads us to the second hypothesis: Rectification may not be occurring in the phono cartridge at all.

The fact is that dominant tuning may depend on the relative position of two components, and the audio cable running between them may function as the antenna. The simplest action is of the trial and-error type: Move the turntable, or preamp, or amp, or all three, or every component you own into new orientations by the compass and into new positions relative to each other. If nothing else, you may end up with a lovely new arrangement of the living room.

REROUTE GROUNDS. Even if you don't succeed in isolating a rectification point precisely, with a little luck it is sometimes possible to bypass it. If you have a separate preamp and amplifier, try taking an independent wire and connecting the two chassis from ground to ground. You can also try a wire from the amplifier ground to the house cur rent ground (the screw in the center of the switch plate on the power outlet). Or you can go from chassis ground to earth ground (the old connect-it to-the-water-pipe routine). When these tactics are successful, the RF may still be there, but you will have simply rerouted it around the unidentified rectifying junction. Of course you may also have picked up some unwanted hum in the process by forming ground loops, in which case you should disconnect the extra ground wire or wires and try another approach.

IMPROVE SHIELDING. The shielding on the audio cables (patch cords) may be inadequate or nonexistent. If the patch cords are not made of shielded cable, replace them with cords that are. If they are made of spirally wrapped shielded cable, try re placing them with the braided type (theoretically, your dealer should know which is which). In some cases you will be forced to abandon simplicity al together and replace the standard audio cables with foil-shielded wire (such as Belden cable #8451), which has two conductors to connect to the phono plugs in the normal fashion, plus a foil wrapping that is in contact with a bare wire. In each cable the bare shield wire should be terminated only at one end and on the ground of a phono plug, preferably at the center of the system.

WRAP AND TRAP. Long audio cables and AC power lines can both collect RFI. You may be able to prevent the RF current from entering an amplifier (or any component that you suspect of audio rectification) by applying the following gimmick.

Get a ferrite transformer core from an electronics dealer or an old TV set-one in which the hole in the middle is big enough for line plugs to go through and still have room. Now take a suspected cable/line cord, pass it through the center of the core, and wrap it spirally around the ring several times to form a coil. This constitutes a "common mode trap." The device will pass a differential (two-way) signal, such as AC, but will inhibit a common-mode signal, one that is induced equally on both conductors and is traveling in the same direction on both. The RF is a common-mode signal, and we can hope that you will eventually find a cable or cord on which the wrapping procedure makes the RFI disappear.

Resort to major surgery. We are running out of simple tactics. You can replace the lamp-cord speaker lines from your amplifier with shielded cable. You can resolder all the phono plug sockets in sight. But if you still have RFI, you will have to consider corrective circuitry, which means wiring in filters or bypasses, usually inside the chassis of the audio components. If you want to try this your self, you can find relevant schematic diagrams in The Radio Amateur's Handbook, in William Orr's Radio Handbook, in The Audio Cyclopedia, and in the April 1975 issue of Radio-Electronics magazine.

If you are not prepared to translate the schematics into hardware, call a high fidelity repairman, and get out your checkbook and practice writing large numbers until he arrives.

But be philosophical. Puttering and soldering aside, surely the inscrutability of our electro magnetic ocean is most interesting. Some emanations, for example, seem hard to explain as errant human broadcast information. A friend of mine, who used to frequent a fried-chicken restaurant (sole tenant in a remodeled old carriage house), re ports that late at night the building sang a bleeping song that sounded like a Grade-B science-fiction movie. The song was finally found to be coming from the old brick chimney. There was nothing on the roof: no telephone lines, no antennas, no metal junctions. And the song came only around mid night-at the witching hour. Curiouser and spuriouser, as Alice might have put it.

------

(High Fidelity, Mar. 1976)

Also see:

Link | --Link | --Link | --Link | --The Best Tape Recordings You'll Ever Make-- by Robert Long and Edward J. Foster. How-to with graphic aids.