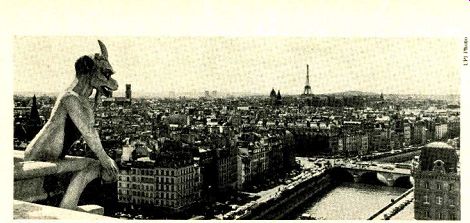

Eric Salzman reports on the "Paris Autumn" Festival AUTUMN in Paris ... duh-duh-duh dah dee ... Paris is a pleasant place to be-at least before winter fog and damp set in- and, for whose who can afford it, it is still a city devoted to the art of living well. But Paris is also, for better or worse, a city rushing to catch up with the twentieth century before it slips away into the twenty-first; so the French capital now has smog, traffic, high-rise apartments in Montparnasse, and suburban shopping centers. It has also demonstrated an admirable desire to climb out of the creeping mediocrity and provincialism that had nearly overcome its artistic life in the last decade or so.

The "Paris Autumn" is a festival intended to bring Paris to the world as much as to bring the world to Paris. It was organized with the avowed intent of bringing the best new art from everywhere to France and of trying to create a new audience, a new awareness, and, above all, a new artistic "scene" within which new ideas can flourish. And, to a degree, it has worked. For three months every fall Paris once again feels like the artistic capital of the world.

For more than a quarter of a century, Paris, like some great, dyspeptic old dowager, has been living on her reputation while becoming increasingly more cut off from the world around her. This closed attitude seemed to express itself in many areas of French life:

rudeness toward foreigners, for example, or the attitude of mistrust and even anger among the French themselves. Literature and film (in France it is almost a branch of literature) are less immediately dependent on the existence of a "scene" and therefore were less affected.

But the visual arts--traditionally an area of French dominance--and the performing arts were overcome by mediocrity and bureaucracy; leadership quickly passed elsewhere, mostly (to the chagrin of French intellectuals) to America.

The most shocking symbol of the decay of French artistic life was composer-conductor Pierre Boulez, an authentic home-grown innovator in the very best French tradition, who could not continue to work and create in his own country and had to go to Germany, Eng land, and America to achieve his present eminence. Well, France has changed and even Boulez will be going back home.

The turning point in France occurred in May of 1968--the famous student rebellion.

That aborted rush to the barricades created a whole new spirit in French life. A silent generation came to life, and the new French public--like the new public here--is young.

Avant-garde art was and is for many young people an expression of faith and contemporaneity, a blow against worn-out tradition, and an affirmation of the future.

The French government, partly in the hope of keeping the peace and partly to retain France's image of cultural leadership, has supported new art fairly generously. It sup ports the Paris Autumn, and the new public has responded in kind. Interest and enthusiasm are high, the succession of events astonishing. Slowly but surely, the climate is changing; Paris is beginning to feel like the New York of ten years ago.

The autumn festival covers music, dance, the theater, and the visual arts. Under the shrewd and knowing direction of Michel Guy.

the festival has been host to (among others) Richard Foreman's Ontological-Hysteric Theater from New York, the Wroclaw The ater Laboratory of Jerzy Grotowski, Grupo TSE from South America, Maurice Mart's Ballet of the Twentieth Century, a pack of young dancer/choreographers from New York, music and dance from the Court of Korea, Jean Dubuffet's "Coucou Bazar" (with music by Ilhan Mimaroglu), the Xenakis Polytope 11, the young American composer Phil Glass and his group, the Philadelphia Composers' Forum, and a new production with the ballet of the Paris Opera choreo graphed by Merce Cunningham with music by John Cage and decor by Jasper Johns (undoubtedly the most ambitious and, for the dance-minded but traditionalist French, the most sensational event of the festival).

THE above events-music and all-were actually separate from the Journees de Musique Contemporaine, an eleven-day festival 1,ithin the festival and itself made up of two separate projects conceived and put together by the French critic and festival director Maurice Fleuret. The first of these was the complete works of Anton Webern--posthumous works and all-in six concerts with l'Orchestre de Paris and Carlo Maria Giulini, the French Radio Orchestra under Gilbert Amy, the North German Radio Orchestra of Hanover and Hamburg Radio Chorus under Friedrich Cerha, the Parrenin Quartet, sopranos Catherine Gayer, Rachel Szekely, and Emiko Ilyama, the pianist Carlos Roque Alsina, and many others.

This astonishing overview of the works of a man who was, for a time, the most influential twentieth-century composer suggests immediately his very secure and very historical niche. Webern was-didn't we always know it?-an exquisite, intense, highly personal artist, somewhat precious, quite in the great (Central European) tradition and quite inimitable. His work is far from uniform: the early, traditional works are quite weak and surprisingly padded. The expressionist atonal works are, almost without exception, wonderful.

The early twelve-tone works, including the much-performed and much-vaunted Symphony, are (one must finally admit) unbelievably awkward and ugly. Only after a struggle did Webern actually master the Schoenbergian twelve-tone idea and produce the beautiful final synthesis of the three cantatas.

THE other half of the festival within a festival carried the rather mystifying title of "Degree Second." With this label, Fleuret wanted to point up and bring together some examples of the rather extraordinary tendency of recent European avant-garde music to base itself on or otherwise take off from earlier music. It is really surprising to note how much new European music employs one or another form of this idea. We are already familiar with Karlheinz Stockhausen's Hvmnen, which uses various national anthems, and with Luci ano Berio's Sinfonia, which incorporates a whole movement out of Mahler. Less familiar is the piano music of Paolo Castaldi-a whole program's worth of generous slices of Roman tic keyboard music amusingly stitched togeth er and performed as a kind of theatrical meta-recital- hands in the air, second thoughts, arrivals, departures, and all.

Mauricio Kagel's Variations Without Fugue for Large Orchestra, after "Variations and Fugue on a Theme by G. F. Handel, Op. 24 of Johannes Brahms" is therefore distinctly third degree. Furthermore, although the title does not mention it, Kagel's work included appearances by two of the three composers: Brahms represented by an actor in costume coming down the aisle reading his letters (in French!), while Handel, bewigged, appears from backstage with an expression of concern. I didn't care for the music itself very much; however, I am going to take care of that little problem by writing a Fugue With out Variations on "Variations Without Fugue for Large Orchestra, after 'Variations and Fugue on a Theme by G. F. Handel, Op. 24 of Johannes Brahms' by Maurizio Kugel," and I plan to ask Kagel to appear in the performance reading from his program notes.

Also on the festival program: Kagel's wonderfully outrageous Beethoven anniversary television film Ludwig van; Stockhausen's television film Telemusik: Johann-Simultaneous Bach. a musical happening devised by Fleuret with various participating artists; other keyboard, vocal, and chamber works on the degre second theme; and, most unlikely of all, a recital by Cathy Berberian consisting entirely of songs set to famous tunes of classical composers with texts ranging from Geraldine Farrar's words for the Air for the G String to Sigmund Spaeth's music-appreciation lyrics of ill fame. The last item brought down the house and produced a twinge of nostalgia in me. I used to collect lyrics for classi cal tunes myself ("Morning was dawning and Peer Gynt was yawning; a coconut fell on his head") and occasionally even used to make them up myself. (Try the Mozart G Minor Symphony to "Take a bath, take a bath in the bathtub; take a bath, take a bath in the bath tub; take a bath, take a bath in the bathtub; take a bath, take a bath in the bathtub; don't forget to take your shoes off. . ." and so on.) There were two principal weaknesses in the festival. One was the unevenness of the performances, particularly those involving French orchestras-quite obviously unfamiliar with and rather unprepared to play this music. Of course, the performance level of visiting artists, such as Cathy Berberian or the choirs of the North German Radio, was high, but with some honorable exceptions the home forces were the least impressive.

A second point concerns the exceptional lack of American works in the Journees. This was particularly surprising, not only because new American art figured so prominently in the rest of the festival but also because the "second degree" idea in new music was so clearly an American development, with specific origins in the work of Charles Ives and many reference points in John Cage. George Rochberg was certainly a pioneer in this field; other examples include Lukas Foss' Baroque Variations, Murray Schafer's Son of Heldenleben (Canadian, to be sure, but indubitably North American), Michael Sahl's A Mitzvah for the Dead, several works by William Bolcom, my own The Nude Paper Sermon and Foxes and Hedgehogs, and many other works from the 1960's. Berio's and Stockhausen's adaptation of earlier music in Hyninen and Sinfonia represents a real departure in their music and a distinct American "influence." However, except for a rather (unfortunately) unsuccessful concert by the Philadelphia Composers' Forum (a group improvisation, a Rochberg piece, and a long work by the group's director Joel Thome), there was no American music at all in the Contemporary Music Days proper. But then there was very little French music either! STILL, there is no doubt that in some very essential ways the festival--the larger Paris Autumn as well as the Journees de Musique Contemporaine- was a success. Most impressive of all were the large and attentive audiences that turned up at the newly refurbished Theatre de la Ville (excellent acoustics), the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris, and one or two other locations for two or three events a day for eleven days.

Stockhausen (who directed the live version of Hymnen twice) and Berio (who also conducted his own music), as well as Cathy Berberian and other exponents of new music, have reached the status of stars-almost pop stars, one could say with only a slight measure of exaggeration. I am no fan of the "star system," but there is very definitely something to be said for a cultural situation in which the creative artist is regarded with respect and admiration. And there is something to be said for critics like Fleuret who, far from trying to maintain the meaningless (and impossible) stance of objectivity, decide to play a committed role and help create an ambiance within which new ideas can flourish. In America the "cultural explosion" seems to be over; mediocrity and bureaucracy seem to have over whelmed arts management and the state councils; the big foundations, twice shy, seem to have backed out altogether, and all the unions seem to be out on strike. Meanwhile, American artists, creativity, and new arts are being feted in Europe. Once upon a time American artists went to Europe; then ten or fifteen years ago European artists began coming to America. They still do so, but there are fewer and fewer each year. Is the new reverse expatriation about to begin?

----------------

Also see:

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF NEGLECTED FRENCH MUSIC--There are still many gaping holes in the specialist's library, RICHARD FREED

Link | --GUIDE TO UPGRADING The when, what, and how of replacing your components JULIAN D. HIRSCH (June 1974)