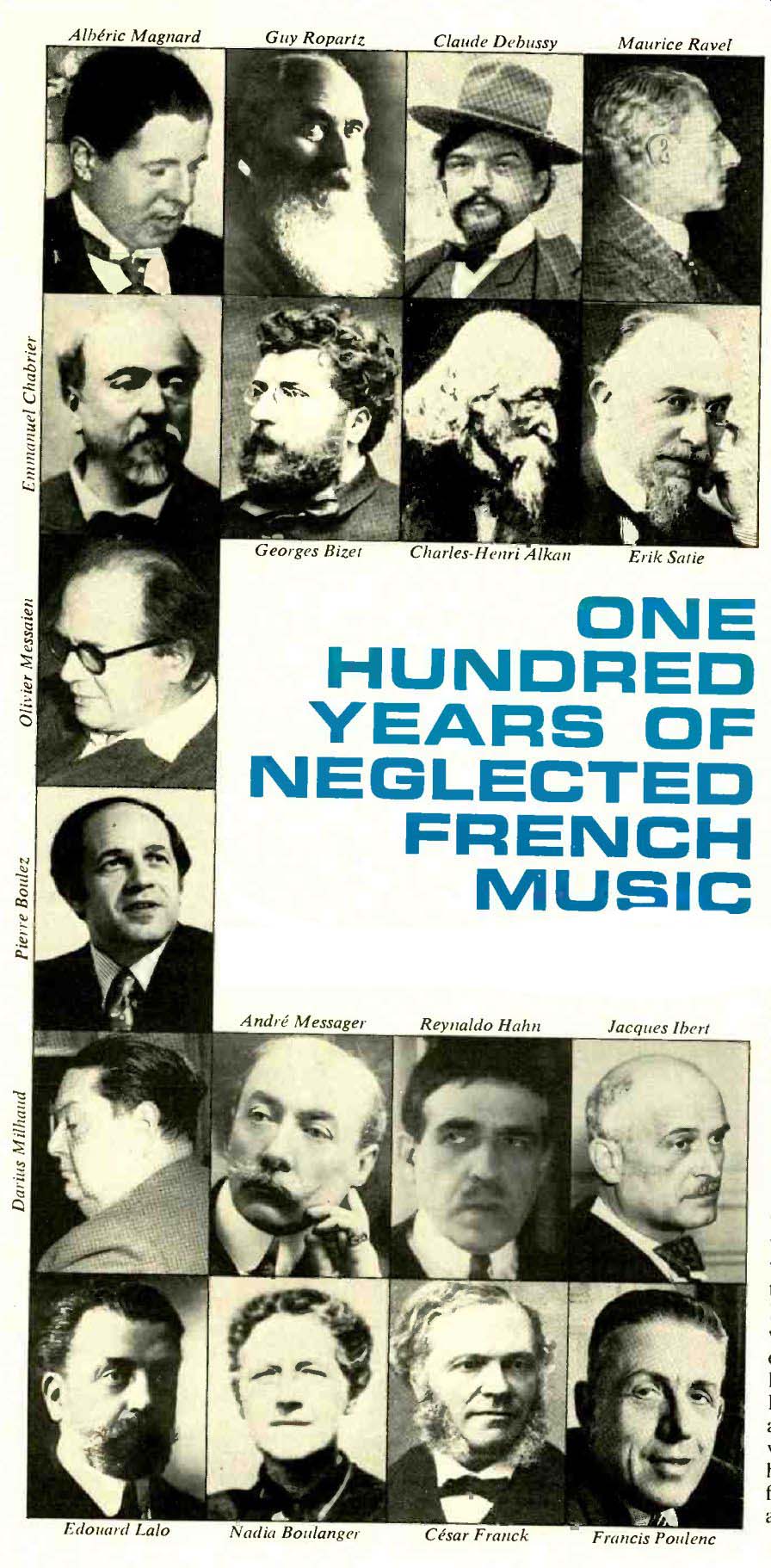

Alberic Magnard

Guy Ropartz

Claude Debussy

Maurice Ravel Edouard Lalo

Georges Bizet

Charles-Henri Alkan

Andre Messager

Reynaldo Hahn Jacques !bell Nadia Boulanger Cesar Franck Francis Poulenc

A specialist's library assembled by Richard Freed

Last year marked the centenary of the births of Sergei Rachmaninoff and Enrico Caruso, with Feodor Chaliapin and even Max Reger, of course, coming in for their share of centennial attention as well. But, as the foregoing examples may suggest, we do tend to concentrate our celebrations in any given year in favor of the bigger name, the glossier reputation, with the result that many a worthy candidate for commemoration is forgotten. The year 1973, for example, might have been an opportunity to rediscover a few French composers (and their music) we may have heard of and forgotten or never heard of at all: Jean-Jules Roger-Ducasse (1873-1954), Henri Rabaud (1873 1949), and Deodat de Severac (1873 1929). No one of them is a monumen tal figure, surely, but they are interesting ones.

It takes a really determined curiosity to verify that statement, for these three Frenchmen share not only a common centenary year, but also the common fate of having their music almost totally forgotten both at home and abroad. Quite a number of their compatriots- specifically, composers active during the last hundred years share the latter bond with them; as Harry Halbreich observes (in his an notation for the Musical Heritage Society set "The French Piano School," MHS-1155/1157), "Not Germany or any other nation can claim such a line-up within the period in question-but the Germans cultivate and honor a Reger or a Pfitzner, and the French don't even know Magnard and Ropartz!" Debussy and Ravel cast long shadows, and they effectively obscure all but a handful of their contemporaries and near-contemporaries.

French music of the last one hundred years is a remarkable category, embracing, in addition to Debussy, Ravel, and "Les Six," the still underrated originality of a Chabrier, the foreshortened promise of a Bizet, various creative responses (both positive and negative) to Wagner and the Russians, the eccentricity of the for ward-looking Alkan and Satie, the enduring benevolence of Faure and Pierne, the latter-day ascendancy of Messiaen and Boulez (whose status as a conductor is a fairly recent development compared with his long history as a composer), and a peculiar fascination with certain instruments and instrumental combinations.

Ignoring that small army of French organists who composed so prolifically for their instrument, and forgetting the celebrated Debussy, Ravel, Milhaud, Messiaen, and a few others, we might list at least two dozen lesser-known Frenchmen (and women) whose work is worth investigating.

The mention of Jean Francaix, Charles Koechlin, Henri Dutilleux, or Andre Jolivet may draw no more response than the names of Severac and Magnard from music-minded Americans, and a reference to Albert Roussel, Andre Messager, Reynaldo Hahn, or Gabriel Pierne is not likely to raise more than a flicker of recognition. Jean Martinon's name will be recognized at once, but few here are aware that the famous conductor is also a composer of stature. Jacques Ibert we know for his once-popular Escales, Edouard Lab for his Sym phonic Espagnole, Chabrier and Dukas for Espana and The Sorcerer's Apprentice, respectively. Is it possible they wrote more? It is, they did, and phonographic attention to this repertoire has deepened appreciably in the last few years, with conspicuous activity on the labels of the Vox group and the Musical Heritage Society.

The fastidious craftsmanship, elegance of style, and overall refinement exemplified by Ravel have been distinguishing characteristics of French music since the time of Francois Couperin. The strong continuity of this tradition is accounted for, in part, by the almost equally prominent tradition of longevity among French composers, a tradition which goes back at least to Rameau. Those with an eye for such things will find a sizable contingent of French musicians who not only lived well into their eighties but continued at that age to be active as composers, teachers, per formers, and all-round "influences" (Darius Milhaud and Nadia Boulanger are today's outstanding examples) --a factor by no means to be discounted in explaining the maintenance of the standards and general outlook that continue to characterize French music at its best.

The greatly beloved Gabriel Faure (1845-1924) did not quite make it to eighty, but his long life, which saw the birth and death of Debussy, Mag nard, Chausson, and Severac, enabled him to emulate Haydn's relationship with Mozart by "learning" from younger composers who had themselves learned from him (such as Ravel, who composed his Pavane pour une Infante Defunte while studying with Faure and who subsequently dedicated his String Quartet and other works to him). Faure wrote several of his finest works in his seventies- both of his cello sonatas after Debussy's death and the solitary String Quartet in the last year of his own life-and they show that, while he retained his individuality, he did not live in the past. (Indeed, when Faure became director of the Paris Conservatoire in 1905, the reactionaries of the day complained that he was turning the institution into "a temple for the music of the future." Ironically, one of his first acts was the introduction of Monteverdi and Palestrina into the curriculum.) Gabriel Faure It cannot be said that Faure is either unknown or in the "one hit" category of Dukas, but few of his works are widely performed, and most of the half-dozen-or-so familiar items (the Requiem, Ballade for Piano and Orchestra, Pavane in F-sharp, Pelleas et Melisande, and a few others) are relatively early works. The later ones, particularly in the realm of chamber music, constitute one of the most rewarding areas still awaiting wide spread discovery.

Faure wrote very little for orchestra, and in some cases he left the actual orchestration to associates. The very rarely heard Prelude to his opera Penelope and his last orchestral com position, the suite from the stage entertainment Masques et Berga masques, are conducted by Ernest Ansermet on London CS-6227, together with the Pelleas suite and the Debussy-Busser Petite Suite. Basic to any Faure discography now (and to any representative collection of French music) is the MHS five-record set of the chamber music (two piano quartets, two piano quintets, two violin sonatas, two cello sonatas, and the two valedictory works-the Piano Trio and the String Quartet); performances on M H S-1286-1290 feature such musicians as cellists Paul Tortelier and Andre Navarra, pianist Jean Hubeau, and the Via Nova Quartet.

Evelyne Crochet has recorded all of Faure's piano music in two three-disc Vox Boxes (SVBX-5423/5424), and Grant Johannesen has done it for Golden Crest in three two-disc sets (S-4030, 4046, 4048). There are two or three recordings now of the Dolly Suite for piano, four hands, in its original form (a good one by Walter and Beatriz Klien on Turnabout, another by Genevieve Joy and Jacqueline Robin-Bonneau on MHS), but even more attractive is Henri Rabaud's composer-authorized orchestral version, conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham on Seraphim S-60084, a disc made up entirely of French bon bons (music from Delibes' Le Roi S'Amuse, Debussy's L'Enfant Prodigue, and Gounod's Romeo et Juliette as well as "standards" by Saint Saens and Berlioz).

Of similar importance, both as a composer and as a major influence in 2 French music, is Vincent d'Indy (1851-1931), a pupil of Cesar Franck (whom he glorified rather naively in art almost fictional biography), one of the founders of the Schola Cantorum (in 1894), and president of the prestigious Societe Nationale de Musique.

His catalog of compositions is larger and more varied than Faure's (fewer songs, but many orchestral and choral works, six completed operas, much piano and chamber music), but far more uneven in quality. D'Indy had different aims and a more restless nature; he was influenced strongly by his mentor Franck, by Bach, Beethoven, and Berlioz, and by Wagner, whose principles he sought to modify as the basis of a new French music.

D'Indy's opera Fervaal, intended as an epic French nationalist work, showed the Wagnerian strain, and its successor, L'Etranger, produced in 1903, ignited a rivalry between partisans of d'Indy and those of Debussy which was to roll on until the beginning of World War I. To their credit, the respective composers themselves did not participate in this skirmish between "sensuality" and "foreign intellectualism": Debussy, in fact, included in his book Monsieur Croche the Dilettante-Hater an enthusiastically laudatory chapter on d'Indy and L'Etranger, observing: "Say what you will, Wagner's influence on Vincent d'Indy was never really profound: Wagner was a strolling player on the heroic plane and could never be linked to so strict an artist as d'Indy. If Fervaal owes something to the influence of the

Wagnerian tradition, it is protected from it by its conscientious scorn of the grandiloquent hysteria which ravages the Wagnerian heroes." It is possible to overlook "the influence of the Wagnerian tradition" in the music of d'Indy known to us, for the more pronounced influences of Franck and Berlioz led d'Indy to shape a vocabulary very much his own. What is known to us, in general, consists of only two works: the Sym phony on a French Mountain Air and the orchestral variations Istar; nei

Vincent D'Indy

ther is performed with great frequency. The latter is an ingenious illustration of the "program," in which Istar is divested of her garments, one at a time, by the warders of the seven portals of the underworld; the theme it self, representing the naked heroine, is not revealed until the very end. It is a gorgeous piece of orchestration--lush, opulent, and not the least bit in conflict with the sensuality of Debussy's Afternoon of a Faun, with which it is roughly contemporaneous.

One of d'Indy's finest orchestral works, perhaps his true masterpiece, is the Second Symphony, in B-flat, which makes use of one of the themes used earlier in the Symphony on a French Mountain Air; it is an astonishingly beautiful score, one in which Tristan and the Sirenes seem quite happy together. What is more astonishing still is that a work so beautiful and so highly regarded by those who know it can be so utterly ignored.

Apparently the Symphony has not been performed (in the Western Hemisphere, anyway) since Pierre Monteux and the San Francisco Symphony recorded it for RCA Vic tor more than thirty years ago. There was a short-lived LP reissue of that recording in the early Fifties (LCT 1125), and recently there was talk of reviving it on Victrola, with Monteux's Istar as filler, but RCA has now shelved its Monteux project.

Not even Istar is available on records now, so let us hope that RCA will reconsider.

At present, apart from the Symphony on a French Mountain Air, the active d'Indy discography includes only three titles, all non-orchestral, all un familiar, but worth getting to know: Jean Doyen leads off his "French Piano School" collection (MHS 1155/1157) with Le Poeme des Montagnes, violinist Henri Temianka and pianist Albert Dominguez play the Sonata in C on Orion ORS-73105 (with Lalo's Violin Sonata in D), and Vladimir Pleshakov plays the Piano Sonata in E Minor, regarded as d'Indy's most ambitious and fully realized keyboard effort, as well as a more generally recognized (if hardly heard) landmark of French piano music, Dukas' Variations, Interlude and Finale on a Theme of Rameau, on another Orion disc (ORS-7266).

Paul Dukas

The Dukas work is available in two fine recordings now. In addition to Pleshakov's (which is followed by Dukas' elegy for Debussy, La Plainte, au Loin, du Faune), there is a newer one by Grant Johannesen, a specialist in the French repertoire, who plays works of Severac and Roussel on the same disc (Candide CE-31059). On yet another Orion record (ORS-6906), Pleshakov introduces us to the Dukas Sonata in E flat Minor (and to Chausson's Quel ques Danses, a work which, like the Roussel items played by Johannesen, is also in Doyen's MHS album). Both the Variations and the Sonata give evidence of a master from whom one is eager to hear more-but there is not much more to hear.

For a man so long and intensely active, Dukas left but a small catalog of works when he died a few months short of his seventieth birthday. He had taken care to destroy the compositions he considered below his standard, and most of what he chose to publish maintains the extraordinary level of imagination and technical mastery evident in The Sorcerer's Apprentice and these two piano works. Only three years younger than Debussy, Dukas studied at the Conservatoire with one of Debussy's teachers, Ernest Guiraud, whose opera Fredegonde he completed, in collaboration with Saint-Satins, after Guiraud's death. Dukas' own opera Ariane et Barbe-Bleue (1907) has a text by Maurice Maeterlinck, the author of Pelleas et Melisande, who conceived Ariane from the outset as a work for which Dukas would provide the music; it is regarded as one of the finest works in its genre, but it is never heard now, and it is not recorded.

Jean Martinon and the ORTF's Orchestre National have now re corded all of Dukas' orchestral music on two discs for different companies.

For EMI, they have done the Sym phony and the Prelude to Ariane. No U.S. release is planned for that disc, but MHS has already issued Martinon's Erato recording of La Peri (the voluptuous "poeme danse," with the introductory Fanfare composed as an afterthought), the early Overture to Corneille's Polyeucte (which does have echoes of the Venusberg), and the ubiquitous Sorcerer's Apprentice.

Albert Roussel Dukas' name has, in any event, been kept before the public uninterruptedly by his one big hit, but the music of the more prolific and no less gifted Albert Roussel (1869-1937) has only recently begun to make in roads into the international scene. As Nielsen and his music remained in the shadow of Sibelius until some years after World War II, so Roussel and his work were largely overshadowed by Ravel. Roussel was born about midway between the births of Debussy and Ravel, and he died in the same year as Ravel, who, although younger than he, was widely recognized be fore Roussel embarked on his career.

Roussel does share many characteristics with Ravel-the brilliance, the polish, the elegance, the strain of refined exoticism-but his style is leaner, veering toward neo-classicism; a page of lush harmonic coloring and sinuous melodic line is likely to be set off by a sequence of spiky rhythms and dryish textures. His finest works were written quite late in life: the ballet masterpiece Bacchus et Ariane, the last two symphonies, the Suite in F, Petite Suite, Piano Concerto, Cello Concertino, and String Quartet all came during his last dozen years.

--------------

THIS MONTH'S COVER

Ada Calabrese's timbrage (from French timbre, a postage stamp, and collage, an artistic composition of printed matter pasted on a picture surface), which graces our cover this month, was originally conceived as a visual representation of Claude Debussy's La Mer.

Its clarity, wit, and brilliant colors, however, qualify it as a metaphor for much of French music of the past hundred years. Ms. Calabrese's timbrages, assembled from cut and shaped postage stamps, have been exhibited frequently, particularly at philatelic shows, and are a happy lesson that art can come even from the bureaucratic desiderata of our time. JG

-------------

Though the Third Symphony (1930) was one of the works commissioned for the fiftieth anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Roussel's music is still not widely performed in this country, and it is only in the last twenty years or so that a Roussel discography of any proportions has been assembled here. Jean Martinon, who studied with Roussel himself, has been his most ardent champion, both in concert and on records. So far, MHS has issued three of his Roussel records with the Orchestre National: the Petite Suite and the complete score of the ballet The Spider's Feast on MHS-1372, the Second Symphony and its "appendix" Pour une Fete de Printemps on MHS-1201, and both suites from Bacchus et Ariane on MHS-1244. A recording of Roussel's last ballet, Aeneas, in which a chorus joins the orchestra, was released in Europe two years ago and should be offered by MHS soon. (Martinon's more brilliant account, with the Chicago Sym phony, of the Second Suite from Bacchus is on RCA LSC-2806; that disc is twice the price of the MHS and the coupling is the familiar Ravel Daphnis et Chloe Suite No. 2, but it is one of the really outstanding items in this discography.) MHS may also be able to reissue the Munch recordings of the Third and Fourth symphonies, formerly on Epic BC-1318, and the Suite in F, a fabulous performance formerly on Westminster WST-17119 (with Dutilleux's Second Symphony). There is at present a more than acceptable record of the two symphonies con ducted by Ansermet (London STS-15025), but none at all of the Suite in F, the bristling, ebullient work with which Roussel began his richest creative period.

The Serenade, for flute, violin, viola, cello, and harp, enjoying some circulation on records now, is Roussel's contribution to the substantial literature for the peculiarly French combi nation known as the harp quintet and is, in fact, the outstanding work produced for that instrumentation. It is handsomely performed on a Turnabout disc (TV-S 34161) by a Munich group which also offers the Debussy Sonata in which the ensemble is reduced by two (violin and cello omitted) and Ravel's Introduction and Allegro, in which the quintet is augmented by clarinet and second violin.

The Melos Ensemble presents (on L’Oiseau-Lyre SOL-60048, at twice the price of the Turnabout) the same program plus Guy Ropartz's Prelude.

Marine et Chanson for harp quintet.

On MHS-892 the Marie-Claire Jamet Quintet plays the Serenade, the Ravel (with additional personnel), and Florent Schmitt's Suite en Rocaille, one of the four works by that interesting composer on records now.

In contradistinction to Debussy and Ravel, whose string quartets were youthful works, Roussel, like Faure, wrote his single quartet quite late (1932). The Roussel and Faure quartets are paired, in performances by the veteran Loewenguth Quartet, on Turnabout TV-S 34014 (the same performances are also in Vox Box SVBX-570, with the Debussy and Ravel quartets and the only current recording of the Franck quartet).

Those who buy the MHS set of Faure' s chamber music, though, will wish to avoid duplicating his quartet and may turn to MHS-135 1 , on which the Via Nova Quartet plays the Roussel and the unfinished quartet of Ernest Chausson, another most interesting figure.

Ernest Chausson

Chausson (1855-1899) was, like d'Indy, a pupil of Franck and one of the leading representatives of the Franck school. His "big number" is the Poeme for violin and orchestra, but his other works are rarely per formed, though his sumptuous Sym phony in B-flat, with its strong themes and superb colors, is one of the finest of the Franck-type symphonies (many consider it superior to Franck's own). Chausson was another late starter: he studied law before taking up music and was nearly thirty when he began to compose. What might well have been one of the most significant careers in French music was cut short when Chausson died in a bicycle accident at the age of forty four.

Possibly no other composer in France or anywhere else has so enthusiastically endorsed in his works Faure's maxim that "art . . . has every reason to be voluptuous," but there is nothing mawkish or unconvincing in Chausson's aural enticements. The haunting Poeme de l'Amour et de la Mer, one of his most distinctive works, is a superb demonstration of his sensitive and subtle way of balancing sentiment with an unfailing regard for the details of musical design and construction. Angel has given us a marvelous recording of this work, sung by Victoria de los Angeles with the Lamoureux Orchestra under Jean-Pierre Jacquillat (S 36897, with selections from Canteloube's Chants d'Auvergne), and Janet Baker sings the later Chanson Perpetuelle with the Melos Ensemble on Oiseau-Lyre SOL-298 (with music of Ravel and Maurice Delage). Violin ist John Corigliano and pianist Ralph Votapek are the soloists in the only current recording of the concerto for their instruments and string quartet, on Mace MCS-9074. The posthumously published Piano Quartet, played by the Richards Piano Quartet on Oiseau-Lyre SOL-316 (together with Martinu's Piano Quartet), is worth looking into, and, as already noted, there are two fine recordings of the Quelques Danses for piano.

Only one recording of the Chausson Symphony is available now, the early stereo version by Robert F. Denzler and the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra recently reissued on Lon don STS-15145 (with Berlioz's Ben venuto Cellini Overture). One of Chausson's three other works for orchestra, the early (1882) tone poem Viviane (after an Arthurian legend), figures in an interesting assortment of little-known music by little-known French composers performed by the New Philharmonia Orchestra under Antonio de Almeida on RCA LSC 3151. The other pieces on the disc are a similar work by Henri Duparc-Lenore, after the ballad by Burger which touched off the symphony so titled by Raff- and the ballet score La Tragedie de Salome by Florent Schmitt.

Henri Duparc

Duparc (1848-1933) was one of Franck's earliest pupils, and the one the master himself considered his finest. Lenore, composed in 1875, antedates all of Franck's own orches tral works and may actually have influenced both his and Chausson's efforts in this genre. In any event, while Duparc's awareness of Wagner and Liszt is easily discerned, Lenore is very much of a piece with Viviane and Le Chasseur Maudit. Duparc lived long but did all his work early; a nervous ailment at the age of thirty seven left him incapable of further production. His output was small: one other brief orchestral piece, a short piano suite, a vocal duet, and sixteen songs. Ironically, it is the songs, so exquisitely fashioned (Phydile, L'Invitation au Voyage, L'Extase, _Le Manoir de Rosamonde, etc.), that have kept Duparc's name alive, but they are not to be had on records now; surely Philips will make some of Gerard Souzay's recordings of them available again.

-------

Florent Schmitt

Schmitt (1870-1958), whose music makes him one of the most fascinating of the "unknowns," went the Conservatoire route, studying with Massenet and Faure. He was productive well into his seventies in virtually all musical forms (including film scores), and he followed Faure's example in offering his only string quartet as a valedictory work (1948). The influence of his Conservatoire teachers is hard to find in La Tragedie de Salome, which suggests Wagner and d'Indy, but even more strongly Richard Strauss and Rimsky-Korsakov, tempered (as Stravinsky's Firebird is) by an acknowledgment of Debussy. The score bears a dedication to Stravinsky, and is said to have influenced the composition of The Rite of Spring.

(Stravinsky had no orchestral works but the Op. 1 Symphony in E-flat be hind him in 1907, when Schmitt's bal let was introduced; the dedication may have been added in 1912, when Schmitt revised his score to even grander proportions, perhaps under the influence of Petrouchka, which had been premiered the previous year.) There are inescapable reminders of Strauss's Salome (given its first Paris performance just six months prior to the production of the Schmitt ballet), but Schmitt's work, which has parts for an offstage soprano and chorus, was inspired by a poem by Robert d'Humieres, not the play of Oscar Wilde. La Tragedie de Salome, heretofore more heard about than heard, makes a terrific impression; it is good to have two splendid recordings to choose from, the newer one being Martinon's on Angel S 36953, on which disc he also con ducts Schmitt's grand choral setting of Psalm XLV II.

Inspiration came to Schmitt from many sources-Oriental lore, the Bible, Edgar Allan Poe, Hans Christian Andersen-and he was capable of writing on an intimate scale as well as a grand one, as demonstrated in the charming Suite en Rocaille for harp quintet mentioned earlier (in the con text of the Roussel discography).

Certain facets of Schmitt's personality may have mitigated against the success of his music (he was a notorious anti-Semite and pro-Fascist, and led a group of likeminded younger composers in shouts of "Vive Hitler!" during a Paris concert of music by the refugee Kurt Weill in 1933), but perhaps it is time now for the music to be heard and evaluated independent of such considerations.

--

Charles Koechlin

Another of Faure's pupils, and perhaps the most colorful of all, was Charles Koechlin (1867-1950), who also studied with Massenet, though there is little in his own highly original music to suggest it. His enormous catalog runs to well over two hundred opus numbers, and there are more than a few surprises among the titles.

Opus 132, composed in 1933, is The Seven Stars Symphony, whose movements are headed (1) Douglas Fairbanks (du Voleur de Bagdad), (2) Lilian Harvey, (3) Greta Garbo, (4) Clara Bow et la Joyeuse Californie, (5) Marlene Dietrich, (6) Emil Jannings (de l'Ange bleu), and (7) Char lie Chaplin (d'apres La Rueevers l'or, etc.).

Koechlin left himself open to every subject, every influence, every inspiration; he dabbled in dodecaphony when it was new and experimented with virtually every passing style. He encouraged his younger colleagues to do the same, but he never attached himself to any "school." He remained an "original," his unique style at all times honoring the principles of con summate craftsmanship he had absorbed from Faure. It is difficult to accept the fact that Koechlin seems to be remembered now chiefly as a biographer of Faure and as orchestra tor of works by Faure (the Pelleas music) and Debussy (Khamma), for his own music is not only abundant in its quantity and varied as to its "subject matter," but brimming over with unusual colors and rhythms.

Novels, plays, history, and the movies all inspired music from Koechlin (in addition to The Seven Stars, he wrote an Epitaph for Jean Harlow, scored for flute, saxophone, and piano, and an orchestral piece called Danses pour Ginger, "en Hommage a Ginger Rogers"), but the most recurrent single theme in his music is Kipling's Jungle Book, on which he composed a large-scale choral work and four tone poems for huge orchestra-one of which, Les Bandar-Log, has been recorded by Antal Dorati and the BBC Symphony Orchestra (on Angel S-36295, with works of Messiaen and Boulez). The one other Koechlin work on records now is the stunning sequence Ong Chorals dans les Modes du Moyen Age, performed by Jorge Mester and the Louisville Orchestra on the Louisville "First Edition" label (LS-682, with works of Henry Cowell and Robert Starer).

A dozen years before Schmitt wrote his Salome, a ballet on the same theme was composed by ...

--------

Gabriel Pierne

Gabriel Pierne (1863-1937), whose March of the Little Lead Soldiers and Entrance of the Little Fauns-the only pieces of his performed in this country-can hardly suggest the breadth of his catalog or the depth of his serious works. Pierne studied composition with Massenet and organ with Cesar Franck, whom he succeeded as organist at Sainte-Clo tilde. As conductor of the Concerts Colonne for thirty years, he was able to introduce a good deal of new music (the prime form of encouragement to young composers), and it was he who conducted the premiere of The Firebird in 1910. The Entrance of the Little Fauns is the opening number in his own ballet Cydalise et le Chevre-pied, as one is reminded by the attractive Pierne collection conducted by Martinon on MHS-1489: the Suite No. 1 from that ballet, the Divertissements sur un Theme Pastoral, and, with Lily Laskine, the Concertstfick for harp and orchestra.

---- Jean Martinon

Martinon himself, sixty-three now, is one of the more interesting com posers working within conventional forms today; his music testifies to the vitality of the Romantic tradition in concise, boldly drawn statements, thoroughly contemporary in spirit but unruffled by the stunts of the avant gardistes. Martinon is probably the only French conductor to involve himself with the music of Mahler with which his own has little in common except the dominant characteristic of compassion which runs through it all.

Like Pierne before him and his own contemporary Manuel Rosenthal (the brilliant orchestrator of Gaite Porisienne), Martinon has allowed his activity as a conductor to overshadow his substantial accomplishments as a composer, though he did introduce some of his music during his tenure as music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and included his Overture for a Greek Tragedy in his recent tour programs. His impressive Violin Concerto No. 2 has been recorded by Henryk Szeryng, for whom it was written, with Rafael Kubelik and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (Deutsche Grammophon 2530.033, with the Berg Concerto), and his Symphony No. 4 (Altitudes), commissioned by the Chicago Symphony, was played by that orchestra under his own direction on a recently deleted RCA disc (LSC-3043, with Peter Mennin's Symphony No. 7). More striking than either of these is the powerful, luminous Symphony No. 2, titled Hymne o la Vie, which Martinon composed in 1944, shortly after his release from a German prison camp. His recording of it, paired with Henri Dutilleux's Symphony No. 1, should be available from MHS soon, and both the Over ture and the Concerto Lyrique for string quartet and chamber orchestra have been taped by EMI.

Dutilleux (born 1916), a major composer in France, is still ridiculously little-known elsewhere. Munch's recording of the Second Symphony, it is to be hoped, will surface again on MHS, whose catalog now includes his performance of the Metaboles composed for the Cleveland Orchestra. The MHS catalog also lists sever al works of Andre Jolivet (born 1905), Andre Jolivet a pupil of Varese and a co-founder, together with Messiaen, Daniel Le sur, and Yves Baudrier, of the group called "La Jeune France," whose aims were to promote con temporary music within a "national istic" context. Jolivet is "convinced that the mission of musical art is human and religious"; he has been called (by the French critic Bernard Gavoty) "the cosmic musician . . . a free man in the tonal jungle." Especially recommended from his current discography is MHS-137 I , on which Jolivet conducts his Second Cello Concerto (with Rostropovich, its dedicatee) and Five Ritual Dances.

Of all the French composers of the generation following Milhaud's, none carries on the tradition of urbanity, wit, and disciplined craftsmanship with more distinction than Jean Francaix (born 1912), who is also an outstanding pianist (he formed a memorable partnership with the cell ist Maurice Gendron, with whom he has given exceptional performances of Beethoven, Brahms, and others).

In terms of inventiveness and polish, Frangaix has been compared to Rav el, but perhaps a closer likeness would be Poulenc, another composer noted for music richer in charm, grace, and wit than in profundity.

(One of Frangaix's operas, La Main de Gloire, is labeled "histoire macaronique d'une main enchantee.") An exception and, in this context, a counterpart to Poulenc's Dialogues des Carmelites is L'Apocalypse de Saint Jean, an oratorio scored for four vo cal soloists, chorus, and two orchestras, the second of which includes a saxophone quartet, mandolin, guitar, harmonium, and accordion.

While neither L'Apocalypse, Scu ola di ballo, nor the sparkling Concertino for piano and orchestra (probably Francaix's best-known work) is on records now, his chamber music production, which began with the masterly String Trio of 1933 and now numbers ten works (each for different instrumentation), is fairly well represented. Candide is about to release a disc on which Frangaix himself con ducts the Radio Luxembourg Orchestra in his Piano Concerto (Claude Paillard-Francaix, piano), Suite for Violin and Orchestra (Susanne Lautenbacher), and Rhapsody for Viola and Small Orchestra (Ulrich Koch).

THERE are of course more composers very much worth mentioning, and more titles by those already listed here. In the current catalogs are unfamiliar treasures by Ibert, Messager, Massenet, and the altogether wonder ful Chabrier. The heretofore unsuspected Fourth and Fifth symphonies of Saint-Saens have just come to light, and the entire cycle is being recorded by Martinon for EMI. Investigation of this material may bring the listener the excitement of "discovery," but it offers more lasting rewards: the refined blend of disciplined Romanticism, warm-hearted wit, charm beyond measure, and un self-conscious loftiness of purpose makes this body of music unique in its appeal and in its satisfactions. We should not have to depend on some centennial excuse to discover it.

----------------

Also see:

RAYMOND LEPPARD--A scholar-performer who hears-and understands-his critics, ROBERT S. CLARK

Link |