By Peter Mitchell

BECAUSE your stereo system can be no better than its weakest link, and because the phono cartridge is usually the first link, the selection of a cartridge is critically important. If the stereo signal leaving the cartridge is distorted, nothing in your amplifier or in your loudspeakers can restore the lost fidelity. Moreover, the task of the cartridge is extraordinarily difficult: its stylus must be able to resolve groove wiggles that are microscopically small, and it must be agile enough to accurately trace a groove that may change direction 40,000 times per second, all without damaging the fragile groove walls it is moving along.

Phono-cartridge performance has greatly improved during the past decade, in both obvious and subtle ways, induced every major manufacturer to in corporate these improvements in his products. So you can hardly go wrong: virtually any pickup you buy from a reputable manufacturer will prove to be very good in absolute terms and probably audibly better than the cartridge you bought five or six years ago.

As cartridges have gotten better, they sound more nearly alike than formerly--they are, in other words, more closely competitive in performance. But significant, audible differences still re main, and as you shop for a cartridge you should consider not only the inherent virtues of various models but also their suitability for your audio system.

For instance, there is the delicate question of ...

Price

It may seem obvious, but it's worth repeating: if you have a $100 record changer, it would be a mistake to install an exotic $300 imported cartridge in it.

You won't hear the special virtues claimed for the pickup because your tone arm can't provide the delicate guidance the cartridge requires, assuming it would play at all. Conversely, if you have a $400 turntable with a fine low-mass arm, a $30 pickup would likely under-utilize the investment you have made. A rough but generally reliable rule of thumb suggests that a suit able phono cartridge will usually cost one-third to one-half the price of your turntable (although ratios from 20 to 100 percent have yielded fine results in some cases).

Tracking Force

The recommended vertical tracking force (VTF) of a phono pickup is a good index of its compatibility with your record player's tone arm and also a pretty good guide to the relative quality of the various models in a manufacturer's line. Inexpensive record changers typically are designed to function best with a cartridge tracking at 2 to 3 grams; cartridges designed to operate a VTF below 1 1/2 grams should be used only in high-quality tone arms with low-friction bearings.

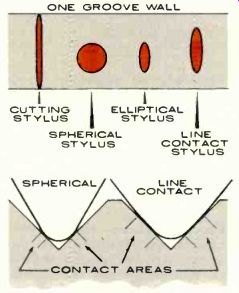

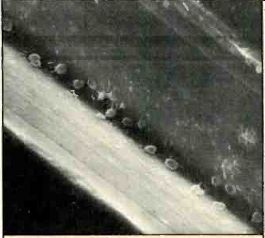

Figure 1. Upper: lateral view of a groove wall showing contact areas of

different stylus shapes. Lower: vertical cross section of a record groove

showing the comparative fit of spherical and line-contact styli.

Some pickup manufacturers specify a single optimum VTF while others specify a range of suggested settings. In the latter case the optimum VTF (yielding the least record wear as well as the cleanest sound) nearly always turns out to be in the upper half of the suggested range. In other words, if the manufacturer's rated VTF range is from, say, 1 to 2 grams, don't expect satisfactory performance at 1 gram unless you have an exceptionally fine tone arm and, perhaps, play un-warped recordings of flute solos. In most arms you'll need a VTF setting between 1.5 and 2 grams in order to track the loudest, most heavily modulated grooves without distortion.

Using a very low tracking force in an attempt to minimize record wear is a mistake. A VTF that is too low cannot maintain the stylus in secure contact with the undulating groove wall during loud passages. When a mistracking stylus bounces off the groove wall (with a burst of harsh, shattering distortion) it produces permanent groove damage.

With a VTF setting near the upper end of the recommended range, the stylus sinks into the groove wall a few millionths of an inch as it passes, but the elastic vinyl quickly springs back to its original shape.

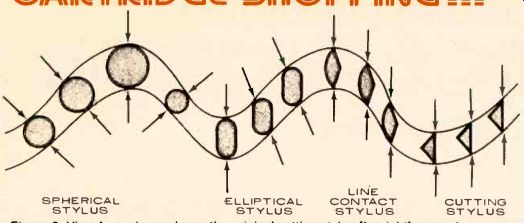

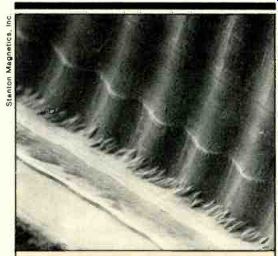

Figure 2. View from above shows the original cutting stylus (far right)

engraving a record groove with channels of information on opposite walls.

A line-contact stylus can maintain the correct tracing geometry; other types

tend to shift the contact area.

Stylus Shape

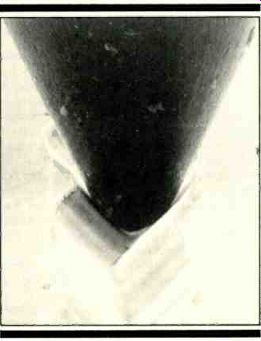

The simplest and least costly styli have spherical (also called "conical") tips. (All styli are actually cone-shaped overall; what matters is the contour at the tip of the cone.) Spherical styli have another advantage besides low cost: they make contact with the groove wall over a relatively large area (called the "contact patch" or "footprint"), thus spreading out the tracking pressure and allowing VTFs as high as 3 or 4 grams to be safely employed without excessive groove wear.

When records are made, the grooves are cut with a sharp-edged stylus, but because of its rounded shape the spherical stylus tip cannot follow exactly the groove contour made by the sharp cut ting stylus (see Figure 1), especially in the congested inner grooves near the label. So, in order to provide more accurate tracing of the groove, the majority of cartridges today employ an "elliptical" or "bi-radial" stylus tip with a narrowed front-to-back dimension. Be cause this results in a smaller contact area, elliptical styli should generally be used only with tracking forces of 2 grams or less.

In recent years manufacturers have developed a variety of "line-contact" styli (Shibata, Stereohedron, Hyperbolic, etc.) which combine a very small lateral "scanning radius," for accurate tracing, with an elongated vertical con tact span that distributes the tracking force over a larger area of the groove wall (see Figures 1 and 2). The most extreme form is the Van den Hul stylus, which is nearly as sharp-edged as a cut ting stylus. Line-contact styli have two drawbacks: high cost and a greater need for critical alignment of the stylus as it rides in the groove.

Transducer Types

Any phono pickup is a transducer, meaning that it converts one kind of energy (mechanical motion of the stylus) into another (an electrical signal).

Much of the vocabulary used to de scribe how cartridges work concerns how this transduction is done. Of course, as is true elsewhere in hi-fi, how it is done is much less important than how well it is done. Moreover, it is important to remember that the transducing mechanism itself is not tracing the groove: the groove vibrates the stylus jewel which is cemented or otherwise mounted on a thin bar or tube (called the cantilever) which transmits the vibration to the transducer in the cartridge body. Many of the improvements in cartridge sound in recent years have resulted from lowering of mass in the tip and reducing distortions caused by cantilever bending and twisting at high frequencies, rather than from any transducer improvement. Still, you'll probably want to know what kind of transducer you're buying. A few very-high-quality cartridges employ non magnetic designs--the electret, for ex ample. However, most transducers operate on a magnetic principle, meaning that a magnetic field is moved through a coil of wire to produce a flow of current in the coil. Cartridges vary mainly in what is being moved-the magnet, the coil, or something between them.

Moving coil (MC). Two tiny coils, one per channel, are mounted on the end of the cantilever so that they vibrate within the magnetic fields of large stationary magnets. Many of the best cartridges are of this type, but they tend to be expensive, stylus replacement may have to be done at the factory, and the miniature coils usually pro duce a low output voltage, requiring a special transformer or pre-preamplifier to step up the signal to normal cartridge voltage levels. Some makers have developed "high-output" MC cartridges that don't need a step-up device. Still, MC pickups are-at least in the U.S.-in the minority; most cartridges are one of the next four versions of the moving-field principle.

Moving magnet (MM). A magnet (sometimes two, one per channel) is mounted on the end of the vibrating cantilever. The magnetic impulses are transmit ted through "pole pieces" (magnetically permeable iron rods or laminations) which transmit the magnetic flux through large coils wound around the pole pieces. This is the most common design.

Moving iron (variable reluctance). The pole pieces include stationary magnets on either side of an air gap which the magnetic flux is reluctant to cross. A bit of non-magnetized iron is mounted on the cantilever so that it vibrates within the gap, varying the flow of magnetic flux across the gap.

Induced magnet. Similar to the moving iron, except that the small iron sleeve on the cantilever is specifically designed to be magnetized by adjacent magnets.

Moving flux. Similar to the moving magnet, but the pole pieces are eliminated and the coils form a close arch around the magnet to pick up its flux directly.

Moving-magnet pickups in particular can be designed to provide large output at low cost (which accounts in part for their popularity), and they can also be refined (usually with lower output) for very good performance.

Compatibility: Impedance

Although it is less true today than previously, most moving-magnet cartridges tend to have a mechanically determined frequency response that rises at high frequencies toward an under-damped ultrasonic resonance. However, the many turns of wire on the cartridge's coils have a fairly high inductance which, coupled with the capacitance of the turntable's signal cables and the input impedance of the preamp, becomes a filter rolling off the pickup's high-frequency output.

If everything has been designed correctly, the rising mechanical response and the falling electrical output neatly nullify each other, producing a flat sys tem response. But if you use significantly different values of cable capacitance and preamp input impedance than the cartridge designer intended, you may alter the effective frequency response by several decibels at high frequencies. Some pickups work best with around 400 picofarads of total capacitance (including both the signal cable and any capacitance in the preamp in put), while other cartridges work best with less than 200 pF. Still others don't seem to care at all. If your amplifier has adjustments for phono-input resistance and capacitance, you can experiment to find the combination of settings that sounds best with your cartridge.

Low-inductance cartridges, a category that includes some moving-magnet designs, all moving coils, and electrets (which have no inductance), are unaffected by cable capacitance and preamp impedance. Since a low-inductance pickup doesn't filter its own out put, its frequency response is essentially that of the stylus assembly, which must be well controlled if the cartridge is to be accurate. (In fact, the perceived brilliance and "clarity" of some low-inductance designs probably result from a rising high-frequency response produced by an under-damped ultrasonic mechanical resonance.)

Compatibility: Sensitivity

Exact matching of cartridge-output and preamp-input sensitivities is not necessary. Modern amplifiers generally have enough extra headroom to accommodate cartridges with higher-than-average output and enough extra sensitivity for pickups with lower-than-average output. But if the cartridge output is substantially lower than 2 millivolts (mV) at the standard test level of 3.54 cm/sec, be prepared to use a relatively high volume-control setting, and expect to encounter audible hum and hiss unless your preamp has a better-than-average signal-to-noise ratio.

Test reports are your best guide to phono signal-to-noise (S/N) figures; manufacturers' specs are often misleading, usually having been measured with a short-circuit input instead of a cartridge. Of course, if you plan to use a low-output moving-coil cartridge, you will need an amplifier that has an MC input (as many do these days) or an outboard step-up device.

Compatibility: Mass and Compliance

The stylus system in a phono cartridge has a springy resilience which is measured as its "compliance." The tone arm has an "effective mass" consisting mostly of the net weight of the head-shell assembly, plus the weight of the cartridge itself. The mass and compliance jointly form a resonant system which tends to vibrate at some very low (infrasonic) frequency. The higher the mass and/or compliance, the lower the resonant frequency; if it is too low (be low about 8 Hz) it will tend to be stimulated by motor rumble, disc warps, footfalls, and acoustic feedback. Too high a resonant frequency can peak the low-end frequency response. Try to avoid the troublesome combination of a high-compliance cartridge in a high-mass arm. (Generally speaking, a high-compliance cartridge is one whose optimum VTF is 1 1/2 grams or less.) Many recently designed tone arms have relatively low mass and are fine for use with high-compliance cartridges, but if you have an older tone arm (or even a new one) with medium-to-high effective mass, stick to cartridges with medium compliance--which is to say those with art optimum VTF above 1 1/2 grams.

=================

A SHORT GLOSSARY OF CARTRIDGE TERMS

Compliance--A measure of the elastic restoring force that re-centers the stylus when it is deflected. The higher the compliance, the less the stylus resists being moved, the less force the groove wall need exert to move the stylus, and the better the low-frequency tracking.

Contact radius--see Scanning radius Effective tip mass--A measure of the inertia of the vibrating parts of the stylus assembly and thus of the tendency of the stylus to continue in a previous direction rather than changing direction when the groove wall does. In recent years tip masses have been halved in many designs, yielding much better high-frequency tracking ability.

Electret--A permanently charged capacitor used as a sensitive transducer in microphones and some phono cartridges. Varying pressure on the electret surface produces a varying voltage output.

Magnetic flux--The energy in a magnetic field. Magnetic flux is conducted efficiently through metals such as iron but comparatively inefficiently through the air.

Mechanical impedance--A measure of the tendency of the stylus to resist being moved back and forth by the groove walls. Essentially determined at low frequencies by the compliance (low compliance equals high mechanical impedance) and at high frequencies by the effective tip mass plus the resistance of whatever damping is included to sup press ultrasonic resonances. The higher the mechanical impedance, the greater the vertical tracking force required to hold the stylus in contact with the undulating groove walls.

Modulation velocity--The strength of the recorded signal is described by the speed (velocity) of the back-and-forth vibration of the stylus (which is not related to the longitudinal speed of the stylus traveling through the groove). The standard reference level used for calibrating phono-cartridge output is a mono (that is, laterally cut) signal with a velocity of 5 cm/sec. The corresponding motion along the 45-degree axes used for stereo is 70.7 percent of that figure, or 3.54 cm/sec. Loud passages in music can produce peak velocities more than ten times higher than that level.

Rake angle--The tilt of the stylus forward or backward from the vertical as it rests in the groove. Ideally it should match the tilt of the cutting stylus, which is angled a couple of degrees back from the vertical in order to scoop material out of the groove as it cuts. Adjustment of the rake angle is said to make an audible difference with line-contact styli, but it is relatively unimportant with spherical and elliptical styli.

Rise time--A measure of response speed, usually tested with a square-wave signal. In a cartridge with approximately flat frequency response, rise time depends simply on bandwidth: the more extended the response, the shorter the rise time. Since low-inductance cartridges (including electrets and moving coils) don't filter their own output, they usually have extended ultrasonic response and the shortest rise time.

Scanning radius--The horizontal radius of curvature of the sides of the stylus.

The smaller the scanning radius, the sharper the stylus edges contacting the groove walls, the narrower the contact patch, and the more accurate the tracing of the finest groove modulations The contact radius, on the other hand, de scribes the curvature of the stylus edge in the vertical direction; the larger its radius, the longer the zone of contact up the groove wall.

Transients--Sudden changes in a signal--such as the beginning of a note or a percussive impact-as opposed to continuous steady-state tones. A square-wave signal is actually a continuous tone, but it involves sharp changes of direction in the groove, so it simulates the difficulty of reproducing transients.

Tracing distortion--A geometric distortion due to the difference in shape be tween the cutting stylus and the play back stylus. The narrower the contact patch where the edge of the stylus touches the groove wall, the lower the tracing distortion.

Tracking ability--The ability of the stylus to stay firmly in contact with the undulating groove wall. With any cartridge, the tracking ability improves somewhat with an increase in vertical tracking force, up to the pickup's maximum VTF.

Vertical tracking angle (VTA)--Stereo involves a mixture of lateral and vertical groove modulations, but, because the cutting stylus is pivoted from a point above the disc surface, its "vertical" modulations actually follow an arc tilted back from the vertical by 15 to 20 degrees (the exact angle depends on the cutter used). For minimum distortion, the playback-stylus assembly should also be designed to swing in the same tilted arc. In actual operation the VTA may be affected by the mounting of the cartridge in the headshell, the height adjustment of the tone arm on the turntable, and the setting of the tracking force.)

================

++++++++++++++++

A Stereo Review Forum on WHAT MAKES A GOOD PHONO CARTRIDGE

Sixteen industry experts discuss the engineering aspects of performance for one of audio’s most highly developed technologies

Moderated by Robed Greene

IT has been said that the wonder of modern record-playing equipment is not that it works so well, but rather that it works at all. This is really a tribute to that marvelous device, the phono cartridge.

Given the hypothetical problem of designing--from scratch--a mechanism to play today's highly refined and complex records (assuming that they somehow existed in a cartridgeless world), engineers might say it couldn't be done. Elsewhere in these pages you'll get some idea of the Herculean tasks (on a minuscule scale, to be sure) these units must perform. They require the highest level of the watchmaker's and lapidary's art exquisitely combined with the sciences of metallurgy, physics, magnetics, and electronics.

Fortunately, however, the cartridge evolved along with the phonograph record. Perhaps the present level of performance could have been reached only through such a process; without the incentive of constantly improving records, cartridge improvement would have been unnecessary, and without cartridges to realize their virtues, improved records would be useless. As a perhaps inescapable by-product of this complex pro cess, the audiophile finds him self inundated with cartridge in formation and misinformation.

To help our readers see what these problems are, how they are being solved, and how the designers feel about them, STEREO REVIEW conducted a survey among the chief technical personnel of a number of cartridge manufacturers. As in previous symposia of this kind, our questions were de signed to draw out fact, opinion, and even emotion. What follows was extracted from nearly fifty pages of technical (and some not-so-technical) comments from our respondents. For the sake of brevity and clarity, we have distilled and at times paraphrased the original remarks. We have, of course, done our best to pre sent accurately the content and intent of our forum contributors' responses. If we have at any point gone astray, we tender our apologies to the parties involved; insofar as we have succeeded, some light should be shed on a much misunderstood subject.

------------------

1. From the standpoint of audible performance, what cartridge measurements are most meaningful?

The great variety of opinion elicited by this seemingly simple question was explained succinctly by Denon: there are no agreed-upon standards for the cartridge specifications quoted by manufacturers. Sonus concurred, adding that "unfortunately, with to day's high-quality cartridges, measurements and specifications are often of little help in defining the subtleties of audible performance." Despite a somewhat pessimistic opening, Denon did note that effective tip mass and stereo separation are the two key specifications from a listening point of view. The tip-mass specification implies a veritable flood of data on how well the cartridge will couple with the record groove, its ability to provide high-frequency detail, the quality of stereo imaging, etc. Nagatronics' position on specifications was that a good frequency response is important and reflects the overall quality of the cartridge, but distortion figures, not frequently published, would be far more revealing and pro vide considerable insight into the performance potential of the cartridge.

Astatic was explicit, listing the measurements in descending order of importance: trackability, frequency response, separation, output level, and inductance. The thread of "track-ability" ran through most of the replies.

Since Shure has been concentrating on just this factor for some time, their reply was not surprising: "Trackability is generally the least understood, the most taken for granted, and the single most important cartridge characteristic. It is the result of a judicious balance of design factors. Insufficient trackability will result in gross distortion. It is analogous in a more complicated way to a low clipping level in an amplifier.

Of course, once good tracking is achieved, other factors such as uniform frequency response and reduction of geometric distortion must be dealt with." The regard for tracking is implicit in B&O's comment as well: "The obvious fact that, to reproduce a record correctly, the stylus must remain in constant contact with the groove and deform it as little as possible is often forgotten in today's world of fashionable, exotic phono cartridges. In spite of many suggestions, no single measurement adequately specifies this ability. Assuming stylus/groove contact, the next most important specification is still probably frequency response." Stanton did not disagree, but their emphasis was different: "A cartridge may track flawlessly, but internal resonances of the moving system and the electrical resonance may change the sound of the pickup. Tracking ability is a basic condition which should be met. From the standpoint of audible performance, frequency response and ability to respond to transients are key specifications once the condition of positive tracking is achieved." ADC detailed different points, but central to them was good tracking: "Assuming no mistracking, a cartridge, in order to be free of the common audible problems, would have no significant amplitude or phase errors in either its mechanical and electrical systems, a fast but well-controlled transient response, and no distortion, particularly odd harmonics." Empire cited low distortion (both phase and amplitude), low noise, a flat frequency response, and good crosstalk, but qualified these concerns:

"However, these are directly affected by tracking ability, stylus design, shape and polish, etc." Adcom and Audio-Technica both under lined frequency response, but with different emphases. Adcom: "Linearity or flatness of frequency response under actual performance conditions is a critical specification. Of course, linearity isn't everything, but lack of linearity is nothing! No amount of money spent to achieve linearity in the rest of the system can overcome the lack of it in the transducer which transfers the sonic image from the record groove. Who today would seriously consider a non-linear preamp or amplifier?"

Audio-Technica's position was slightly different: "The overall smoothness of the frequency-response curve is important more so than the flatness of the curve--because abrupt changes in response are undesirable. Tracking ability also is a key specification because it shows the ability of a cartridge to perform without distortion and record wear. The high-frequency separation measurement is critical since it indicates how well the stereo image is presented." Micro-Acoustics brought in a point not previously mentioned, and with it an interesting explanation: "Audible performance can be predicted by frequency response, separation, distortion, and rise-time measurements. Frequency response measures the balance between low-, mid-, and high-frequency levels. Separation response is an indicator of stereo-image fidelity, and distortion measurements check the fidelity of the reproduced waveform. Rise-time measurements allow evaluation of transient response. Although test records for most measurements use sine-wave signals similar to the simplest musical sounds, actual re corded program material is full of sudden bursts of sound or transients, hence rise time is a key measurement. It is also important that listening tests be carried out with the cartridge operating under the same conditions used during test-record measurements. Improper alignment or mistracking could add sufficient distortion to completely alter a listener's judgment." And, finally, Ortofon cited frequency response, tracking ability, channel separation, and phase as the most important phono-cartridge measurements and specifications.

They did not judge that any one of these is more important than any other, but rather that all must properly interact in order for the phono cartridge to perform properly.

2. How do tracking-force ratings and tracking ability relate to each other?

Micro-Acoustics answered this question with an explanation that included some historical perspective: "The stylus must exactly follow or scan the mechanical waveforms of the record groove, and unless the stylus/ groove contact is continuous, we cannot even begin to reproduce the recorded signals accurately. Tracking ability, then, is a prime quality factor. When our design experience began thirty years ago, 5- to 8-gram tracking forces were not unusual. In an effort to prevent record damage and avoid the need for frequent stylus replacement (every ten hours or so) tracking-force reduction became a prime design objective." Ortofon agreed with the importance of tracking ability and added that "in general, tracking ability improves as tracking force is increased. Tracking ability is also a direct function of the equivalent stylus-tip mass. The lower the tip mass, the greater the tracking ability of the cartridge." Stanton also picked up on this point: "Because of current long-con tact-area / large-bearing radius stylus shapes, pressure per unit area may be much lower than with conical styli; the groove wear is reduced, and distortion products are minimized."

Denon took a very practical point of view: "Such problems as turntable resonance, acoustic feedback, and record warp effectively establish the lower limits on tracking forces. It's clear that cartridges should track below 2 1/2 grams to avoid excessive record wear, but the specific force used should be consistent with overall cartridge/ tonearm mass and cantilever compliance.

Cartridges and tone arms are part of a complex system that must function as an integrated working whole." Audio-Technica pointed out that, in addition to the other ad vantages attained by reducing the cartridge's moving mass, the stylus' resonant frequency is shifted above the audible range, thereby reducing the need to damp it. Reduced record wear is an additional benefit.

Shure commented simply that stylus force is a prime ingredient of trackability, so the maximum tracking ability at the minimum stylus force is a prime quality factor. Sonus felt that tracking ability and tracking-force requirements are significant in that they tend to indicate whether a cartridge has high enough compliance and low enough mass that it can track at relatively low forces. Although tracking ability is seldom a problem per se in modern cartridges, mistracking of a more subtle kind may still be encountered, particularly with some of the new audiophile discs.

Empire's terse comment was that, what ever its origin, any form of mistracking generates considerable distortion.

3. What influence does cantilever material and construction have on cartridge performance?

Audio-Technica's response to this question provided considerable insight into the problem: "The cantilever transmits to the generating element the vibrations which the stylus tip picks up from the record. In order to do this with accuracy, it is necessary for the cantilever to be at once as light as possible and as rigid as possible. The less tendency a cantilever has to flex, the greater its ability to transmit the information in the record groove accurately. However, increasing cantilever stiffness without a corresponding mass reduction may not result in improved performance. Likewise, reduction in mass taken to an extreme may result in a cantilever of insufficient stiffness."

Pickering's view was that exotic cantilever materials should be evaluated on the basis not only of their cost, but on their mechanical performance: "The cantilever should be light, strong, non-resonating, electrically conductive, reasonably easy to manufacture, dimensionally precise, and durable. Cantilever materials like diamonds and sapphires do not meet these requirements in several areas. Most of the exotic materials being used in a relatively small number of very expensive cartridges exhibit fairly high dynamic tip mass. Such a cantilever assembly has sharp resonances at ultrasonic frequencies, and the vibration can damage the groove walls. Solid diamond and sapphire cantilevers are non-conductive, extremely difficult to manufacture, and excessively expensive. The strongest and lightest cantilever shape is a hollow tube. No matter how much lighter than aluminum the basic material is, it is heavier when the cantilever is made of solid diamond or sapphire rod. Other exotic metals may offer better alternatives than diamond or sapphire, but their stiffness-to-weight ratio is not much better than aluminum and their cost is extremely high." Adcom agreed, adding that "sapphire, ruby, and diamond materials offer great promise for future designs, but they offer maximum advantage only when formed into thin-walled tubes (laser drilling is one method)." Astatic agreed, and Shure pointed out that the mechanical characteristics of the cantilever become increasingly significant in respect to a cartridge's tracking ability as the frequency of the recorded signal goes higher. Ortofon indicated that the desirable combination of low mass and extreme rigidity can be achieved by combining different cantilever shapes (stepped designs, tapered designs, etc.) with various construction materials.

Looking at another physical aspect, Empire cautioned that using some exotic space-age material may actually degrade performance unless the material can be fabricated to a design that takes advantage of its special properties.

Denon takes a pragmatic approach, stating that their present use of a vapor-condensed boron cantilever just happens to be their way of arriving at the desired result: "The choice of cantilever material should depend on the overall cartridge design. If it works well, then the material is good. We don't believe there is any magic cantilever material."

4. How important do you find stylus-tip shape in respect to (1) the ability to trace high frequencies, (2) distortion, and (3) the tendency to accumulate dust and groove debris

Ortofon, ADC, and Empire all mentioned that the best performance can be obtained through the use of styli that have a large contact area and small scanning radii, ADC explaining that the former distributes tracking force over enough groove-wall area to prevent excessive groove indentation and the latter extracts high-frequency information from the innermost grooves. But within this general agreement the thinking differed somewhat. Denon and Nagatronics felt that no single tip shape is best for all purposes, and reactions from users of Denon cartridges (which have five different tip shapes available) seem to indicate that preference for the sound and type of distortion produced by each tip shape is essentially a matter of taste. For example, conical tips track worn surfaces with less noise and distortion, but they do so with some loss of musical information.

Astatic and Audio-Technica held that playback-stylus shape resembling that of the cutting stylus is desirable, the latter adding that unfortunately "the greater the conformity, the greater the difficulty in aligning the cartridge precisely." On this point, Sonus indicated that the more exotic tip shapes are very critical with regard to form, polish, and accuracy of mounting: "If great care is not taken with these criteria, one is better off with simple spherical or bi radial tips." Shure pointed out that one important result of the better tracking ability of such shapes is that it minimizes the very-high-frequency distortion that could be shifted down into a more audible part of the audio spectrum through intermodulation.

The only respondent differing somewhat on this issue was B&O, who observed that though shape was vital in the heyday of CD-4 and though it remains a factor in the highest-quality applications of today, other design parameters are more important to basic performance. In regard to the dust problem, B&O said, "Dust accumulation is a function of the polish on the entire stylus surface, not just of the very tip or of the shape of the tip." Shure stated that if the stylus' projection from the cantilever is too short it will tend to retain dust and debris and so necessitate frequent cleaning; if it is too long, torsional (twisting) effects may occur. Stanton commented that accumulation of debris at the stylus tip may be due to electrostatic attraction of the cantilever or to the kind of liquid cleaner used on records or stylus, but that the shape of the stylus tip has little to do with this unless it starts scraping the bottom of the groove. In any case, all panelists agreed that records should be kept scrupulously clean.

5. Do you believe that any one type of cartridge transducer design (moving magnet, moving coil, etc.) is inherently superior?

As expected, a number of companies ex tolled the virtues of their proprietary de signs in terms not much different from those found in their ads. What was a surprise was the number of respondents who, like ADC, felt that state-of-the-art cartridge design is possible with any type of generating system, and that the quality of a phono cartridge resides in the execution of the design.

Shure put their emphasis on "the design of the cantilever, tips, and suspensions, major parts of the cartridge's performance. All designs share these elements, which are not associated with any particular transducer principle." B&O agreed, stating that the means used to transfer stylus movement to the armature is much more important than the type of transducer. Denon makes both moving-coil and moving-magnet types, so they conduct continuing research on both; they assume that the question will remain unresolved indefinitely--except in the mind of the end purchaser.

Stanton felt that the moving-coil designation is frequently a misnomer. In their view, most moving-coil cartridges are actually moving-iron types due to the bobbins (small spools) on which the coils are wound.

If the soft metal bobbins were removed there would be almost no signal produced.

----- " all panelists agreed that records should be kept scrupulously

clean."

They claim that the difference in sound heard from many moving-coil designs is due to "loose wires in the bobbin and those connecting the coil. That extra brightness is due to the harmonics generated by these wires working as an artificial reverberation device." Despite the fact that this effect is pleasing to some listeners, Stanton prefers that signals be reproduced "without enhancement or alteration." Audio-Technica, ADC, Sonus, Shure, and Empire were largely in agreement that the use of a particular transducer type isn't the absolute key to good sound, that good design and proper application are the important factors. Or, as Audio-Technica summed it up: "What type you make is less important than how well you make it."

6. How does tracking force affect record and stylus wear, and what other factors are involved?

ADC pointed out that either too high or too low a tracking force can cause groove-wall damage; for minimum wear and proper tracking, a figure at the center of the manufacturer's specified range should usually be used. Micro-Acoustics commented that tests have shown that dust on the records played can cut record and stylus life in half.

They mentioned that other factors such as arm mass, arm friction, unbalanced skating force, and warped records can all demand increased tracking force for good performance. And Denon also cautioned that too low a tracking force is detrimental to records and styli. After all, a diamond flailing through the groove at massive G forces is all the vinyl needs as an excuse to deteriorate.

The simplest and most effective way to pre serve both stylus and record is to keep them both immaculate.

Ortofon started by pointing out that there is an inverse relationship between record wear and stylus wear that has to be taken into account. They feel, however, that a more important factor is the amount of actual stylus-contact area over which the tracking force can be distributed; the larger the stylus-tip contact area, the lower the record wear. Astatic was generally in agreement with this and with the slightly-heavier-is-better thinking mentioned earlier, and Audio-Technica commented that stylus pressure is the more important consideration: a line-contact stylus permits an in creased tracking force with decreased stylus pressure compared to other stylus configurations. Stanton noted that pressure per unit area applied over the correct part of the groove is the key factor in low record wear.

High compliance is a must for large, low-frequency excursions, and low dynamic tip mass is essential for high frequencies; record and stylus wear are in direct proportion to both of these properties.

Sonus played down tracking force per se as a factor in record wear, stating that as long as it doesn't exceed 1 1/2 to 2 grams and the stylus is well-polished and-mounted, then groove contamination, a damaged stylus, and mistracking are much greater wear factors. Empire held that the shape and polish of the diamond tip are just as important as tracking force.

7. Do you have objections to or preferences for any of the currently available test discs? In general, how valid in respect to revealing cartridge quality are they?

While there was a certain division of opinion among the panelists, the consensus seemed to be that test records can be useful provided one is familiar with their limitations. Audio-Technica felt that their own test discs as well as those from JVC and Shure are "reliable" and those from B & K "useful," but that those from CBS aren't "state-of-the-art." Ortofon was rather neutral, stating that they don't find any of the present test records to be either deficient or superior. Micro-Acoustics provided a "laundry list" of test records (mostly CBS) they like, but each for a specific purpose.

Stanton felt that too much doctoring of test records takes place--and that the most ac curate test records commercially available are those from JVC.

Adcom liked at least two of the CBS test records but found that many other records can give unreliable results. Nagatronics commented: "Most currently available test discs involve a great many compromises, but they do serve as comparison standards within the laboratory." The limitation they find, however, is that because the consumer is unfamiliar with the discs' defects, the required lengthy explanations make the presentation of test results difficult. Shure continued along somewhat the same lines when they said that all test records can give usable results if their calibration is known, but that some aspects are hard to know. For ex ample, there are significant differences in crosstalk with the same pickup measured on CBS STR-100, B & K QR 2009, and JVC TRS 1003, and it is difficult to know which is closest to the 45-degree standard. Test records, they concluded, are useful, but they are no substitute for listening. Astatic and Denon pretty much went along with Shure. ADC's comment was that an almost insoluble problem is created not only by the differences between different records but between different pressings of the same record. Their solution is to choose one record and supplier and then press the supplier to maintain quality and particularly uniformity in his product over time.

Two other respondents were also fairly negative. B&O: "Even test discs cut and pressed under laboratory conditions are of ten inadequate to determine many of the performance limits of the best cartridges.

Use of commercial records as a test of absolute quality is therefore not recommended unless a statistical method can be used to remove the differences." And, finally, Empire, summing up for the cons: "The industry is in dire need of a good standard test record and procedure, particularly for tracking ability, distortion, and crosstalk."

8. What qualities do you feel are most important in a ton arm? Is there an optimum tone-arm mass?

The laws of physics being the governing factors here, all engineers have to work within the same limitations; they may point up varying aspects, but, by whatever means, they must deal with the same problem.

Stated briefly, in order for the cartridge to produce a signal the stylus must move relative to the body of the cartridge, not with it, so the cartridge and tone arm must together provide enough mass to resist being driven by the stylus. At the same time, the total mass must be low enough to be relatively unaffected by such extraneous elements as record warp, off-center (eccentric) records, and external shock and vibration. However, a given combination of arm mass and stylus compliance will inevitably produce a mechanical resonance at some low frequency.

Below this resonant frequency the arm and cartridge will tend to follow the stylus deflection, resulting in a loss of output; above this resonant frequency the arm and cartridge remain stable relative to the stylus and the cartridge is able to produce a nor mal signal. At the resonant frequency, the cartridge overreacts and can jump grooves if the resonance coincides with record-warp frequencies, which are mostly concentrated below about 10 Hz. The engineering trick, then, is to work out the best possible mass/ compliance compromise in order to keep the resonant frequency at the least objection able point.

According to Shure, the optimal combination of effective arm mass, cartridge weight, and stylus compliance should result in a resonance in the range of 8 to 15 Hz.

Stanton pointed out that there is no specific magic resonant frequency but only an approximate range (8 to 12 Hz), since tonearm and cartridge weights and stylus compliances vary considerably. A number of the panelists mentioned figures around 10 Hz.

Audio-Technica felt that while there are optimum tone arms for specific cartridges, there is no optimum arm for all cartridges.

They also stated that the stylus tip should be vertical to the record surface and that the cartridge must be installed firmly.

ADC noted that desirable characteristics in a tone arm are accuracy and stability: "It should be possible to set up a tone arm to Empire summed up the situation succinctly: "An ideal tonearm/cartridge sys tem would have the stylus tracking only the groove modulation, while the tone arm would track only the warp and wow components on the record."

------ " . . . either too high or too low a tracking force

can cause groove-wall damage." meet the proper conditions and then have

it remain that way."

9. How critical, in general, is cartridge installation in respect to sonic performance?

B&O, Pickering, Empire, Astatic, Shure, and Stanton appeared to feel that optimum installation is important, but not a matter of life and death. Shure held that while installation should be done as carefully as possible, minor misalignments do not seem to produce audible disasters. Stanton pointed out that though cartridge installation is important for maximum separation and lowest distortion, even the most careful lateral alignment can be negated by incorrect anti-skating compensation, physically biasing the cantilever off its centered position.

Adcom, however, stated that proper installation is vital, and Ortofon held that it is extremely critical in order for the cartridge to perform at its design parameters. Sonus felt that if both the arm and cartridge are correctly designed, correct installation, al though very important, should be simple and non-critical.

Denon's response was the strongest: "Cartridge installation is absolutely, positively, undeniably critical, and never let anyone tell you otherwise. With geometric factors as small as we are dealing with, what else could anyone expect?"

10. Considering the about-to-be-released all-digital audio discs, what do you feel about the future of conventional LPs and the devices that play them?

Many of STEREO REVIEW'S readers will probably be relieved to learn that the panelists were in virtually universal agreement that, as Audio-Technica put it, "conventional phonograph recordings will be around for many years to come." Shure's reasoning was that the LP will be with us for a considerable time because it affords good value for the money and has many practical conveniences. ADC pointed out that the vast amount of existing soft-wear (records) in the present form will continue to require high-quality devices to play them. Stanton, Astatic, Nagatronics, Micro-Acoustics, Pickering, and Ortofon all held pretty much the same opinion. B&O felt that the digital disc will ultimately re place the present analog type (they didn't say when), and Denon's respondent, despite being very high on digital, says he wouldn't stop buying records in the near future.

Empire felt that a practical digital-disc system will provide little performance ad vantage over a good analog LP system.

They added, however, that "since many technocrats in large organizations believe that a complex state-of-the-art design is al ways better, we will have to accept the inevitability of considerable lobbying for video disc-derived technologies" but that acceptance of a final system may take longer than presently anticipated because of the inevitable major confrontations between different digital systems.

Sonus envisioned somewhat the same kind of future and elaborated: "To be economically viable, industry standards must be adopted, and that will probably not hap pen without a considerable struggle be tween the giants of the industry. Further more, there is a great danger that when such standards are agreed upon, they will be such as to limit the highest attainable fidelity due to considerations of cost. Mean while, the analog disc is still capable of enormous improvement and may render the pure digital disc either unnecessary or economically unjustifiable."

11. Do you have any suggestions to pass on to record-player and preamplifier manufacturers that would make your job as a cartridge de signer easier?

Aside from the single simple request (from Astatic) for a permanent mark on the turn table to indicate optimum tip position, the items our engineers wanted to find in their technological Christmas stockings were complex but fairly uniform. As Ortofon put it, standardization of such parameters as cartridge/headshell overhang and tracking angle, and a standard mounting socket for the headshell, would yield better cartridge and tonearm interfacing and performance.

Concurring with this point of view to one degree or another were Audio-Technica, Shure, and ADC.

Standardized load capacitance in turntable cables and in preamplifiers was called for by Ortofon as well as Audio-Technica and ADC. Pickering would be happy if preamp manufacturers would publish (or even be aware of) the input capacitance of their preamplifier circuits. Also in the preamp area, B&O requested that manufacturers stick to standards established for input impedance and not make "improvements" with oddball values.

Stanton suggested that record-player manufacturers should specify the dynamic mass of their tone arms correctly and with out exaggeration. This would permit the cartridge maker to suggest proper cartridge/tone-arm combinations with specific tracking-force recommendations.

Denon and Adcom were somewhat pessimistic, Denon stating that suggesting standards that will not be met is useless and that it is up to the cartridge manufacturer to make his product workable in as many situations as possible. Adcom's comment was: "Standardization obviously would be helpful, but given the biases of competing manufacturers and differing technologies this is highly unlikely."

12. Are there any other matters you think should be commented on in this subject area?

Audio-Technica brought up quality control: "Intensive quality control is a vital part of manufacturing uniform consumer products. The real measure of quality is whether the same performance attained in a lab report is consistently available to consumers who purchase the product in retail stores." Astatic pointed out that phono-cartridge specifications must be carefully considered in relation to the total system and particularly to the tone-arm/turntable combination in which a cartridge is mounted. They felt that it's their job to give the consumer reasonable choices and recommendations, but that it's also up to the consumer not to misuse equipment for which he has such in formation available if he expects reasonably good performance.

ADC, Denon, and Empire saw transducer design and execution as an evolutionary process that can only get better. Many of the problems, said ADC, are extremely complicated, and all are interrelated, but they are solvable. Empire closed with an old but still valid truism: the most cost-effective improvement you can make in your hi-fi system is to upgrade your cartridge.

THE FORUM PANEL

Duane E. Punkar, The Astatic Corp.

John Kuehn, James O'Neill, and Eric Park, Audio Dynamics Corp. (ADC)

S.K. Pramanik, Bang & Olufsen a/s (B&O) Robert Heiblim, Denon America, Inc.

Roland Wittenberg, Empire Scientific Corp.

Newton A. Chanin, Adcom Norman H. Dieter, Micro-Acoustics Corp.

David B. Monoson, Nagatronics Corp.

George Alexandrovich, Pickering & Co., Inc.

Bernhard W. Jakobs, Shure Brothers, Inc.

Peter E. Pritchard, Sonic Research, Inc. (Sonus)

Norman Levenstein, Audio-Technica

Walter O. Stanton, Stanton Magnetics, Inc.

Henry A. Roed Jr., Tannoy Ortofon, Inc. (Ortofon)

Note: Space limitations precluded our canvassing all existing cartridge manufacturers for this forum.

Those selected, we feel, present a representative sampling of viewpoints.

Also see:

A TURNTABLE PRIMER: What buyers need is a little understanding, by GARY STOCK

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)