In its simplest form, shown in FIG. 1, an audio amplifier consists of an input voltage amplifier stage (A) whose gain can be varied to provide the desired output signal level, an impedance converter stage (ZC) to adjust the output impedance of the amplifier to suit the load, which could be a loudspeaker, a pair of headphones, or the cutting head in a vinyl disc manufacturing machine.

FIG. 1 Audio amplifier block diagram

FIG. 1 Audio amplifier block diagram

In the case of the headphones, their load impedance could be high enough for them to be driven directly by the voltage amplifier stage without a serious impedance mismatch but, with the other types of output load it will be necessary to interpose some sort of impedance conversion device- in tube operated audio systems this is most commonly an iron-cored audio frequency transformer. This is a difficult component to incorporate within a high-fidelity system, and much thought must be given both to its design and the way it is used in the circuit.

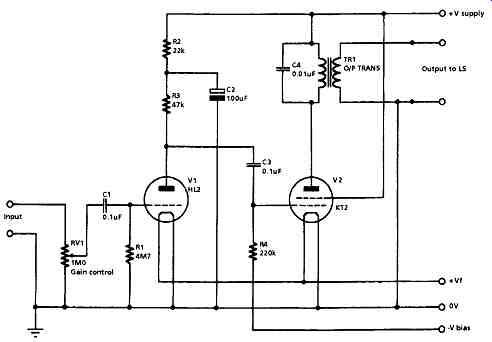

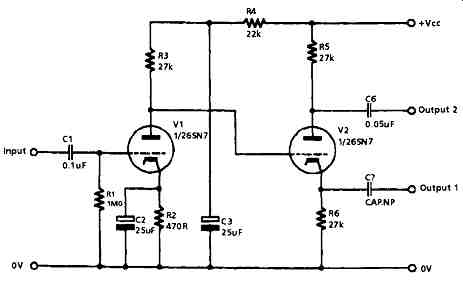

A very simple circuit layout embodying the structure outlined in FIG. 1, using directly heated (battery operated) tubes, is shown in FIG. 2. This is the type of design which might have been built some fifty years ago by a technically minded youngster who wanted some means of driving a loudspeaker from a simple piezo- electric gramophone pick-up.

For the maximum transfer of power from an amplifier to its load it is necessary that both of these should have the same impedance, and since the anode resistance (Ra) of the output tube is of the order of 10kD, and the most common speech coil impedance of an inexpensive moving coil loudspeaker is 3D, there would be a drastic loss of available power unless some impedance converting output transformer was employed.

The primary:secondary turns ratio of this component would need to be √(10k/3) = 58:1. It is difficult to design transformers having such high turns ratios without losses in performance and, in consequence, when higher audio quality was required, the LS manufacturers responded by making loudspeaker drive units with higher impedance speech coils. Before the advent of transistor operated audio amplifiers the most common LS driver impedance was 15 ohm.

With regard to the amplifier design shown, the input stage (V1) uses a simple directly heated triode, with grid-current bias developed across the 4M7-ohm grid resistor, R1, as shown in FIG. 3a. This is resistor/capacitor coupled to V2, a small-power beam tetrode or pentode, operated with fixed bias derived from an external DC voltage source.

Because both V1 and V2 will contribute some distortion to the signal- in the case of V1, this will mainly be second harmonic, but in the output tube (V2) there will also be substantial third harmonic component- the output signal will sound somewhat shrill, due to the presence of these spurious high signal frequency components in the output. The simplest and most commonly adopted remedy for this defect was to connect a capacitor (C4) across the primary of the output transformer (TR1) to roll-off the high frequency response of the amplifier as a whole, to give it the required mellow sound. The HT line decoupling capacitor (C2) serves to reduce the amount of spurious and distorted audio signal, present on the +V supply line, which will be added to the wanted signal present on V2 grid. An amplifier of this type would have an output power of, perhaps, 0.5 watts, a bandwidth, mainly depending on the quality of the output transformer, which could be 150Hz- 6kHz, +6dB, and a harmonic distortion, at 1 kHz and 0.4 watts output, of 10%. The amplifier shown in FIG. 2 uses a circuit of the kind which would allow operation from batteries, and it was accepted that such designs would have a low output power, and a relatively poor performance in respect of its audio quality: this was the price paid for the low current drain on its power source. If, however, the amplifier was to be powered from an AC mains supply, the constraints imposed by the need to keep the total current demand low no longer applied, and this gave the circuit designer much greater freedom. The other consideration in the progress towards higher audio power outputs was the type of output stage layout, in that this influenced the output stage efficiency, as examined below.

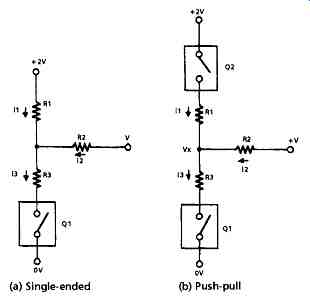

FIG. 3 Output arrangements (a) Single-ended (b) Push-pull

Single-ended vs. Push-pull Operation

These two options are shown schematically in FIG. 3, in which Q 1 and Q2 are notional amplifier blocks, simplified to the extent that they are only considered as being either open-circuit (O/C) or short-circuit (S/C), but with some internal resistance, shown as R3 (or R1 in the case of FIG. 3b). I have also adopted the convention that the current flow into the load resistor (R2) is deemed to be positive when the amplifier circuit is feeding current (as a current source) into the load, and negative when the amplifier is acting as a current sink and drawing current from R2 and its associated power supply. I have also labeled the voltage at the junction of these three resistors as V x. The efficiency of the system can be considered as related to the extent of the change in the current through R2 brought about by the change from o/c to s/c in Q1 or Q2.

If we consider first the single-ended layout of FIG. 3a, when Q 1 is O/C, the current flow into R2 is only through R1. and i 2 = V/(R1 + R2). If, however, Q1 is short- circuited, S/C, then, from inspection,

i3 = i1 + i2 (1)

...but i2 = (V - Vx)/R2 (2)

i1 = (2V- Vx)/R1 (3)

and i3 = Vx/R3 (4)

from (1), (2) and (3) we have

i3 = (2V- Vx)/R1 + (V- Vx)/R2 (5)

...but it has been seen from (4) that i3 = Vx/R3

...therefore (2V - Vx)/R1 + (V - Vx)/R2 = Vx/R3 (6)

If we insert the actual values for R1, R2 and R3, we can discover the difference in output current flow in the load resistor (R2) between the o/c and s/c conditions of Q1.

For example, if all resistors are 10-ohm in value, when Q1 is s/c, V x will be equal to V, and there will be no current flow in R2 and the change on making Q 1 o/c will be (V/20)A. If R1 and R2 are 10f2 in value and R3 is 5fL then the current flow in R2, when Q1 is o/c, will still be (V/20)A, whereas when Q1 is s/c, the current will be (-0.25V/10)A and the change in current will be (3V/40)A. By comparison, for the push-pull system of FIG. 3b, the change in current through R2, when this is 10-ohm and both R1 and R3 are 5-ohm in value, on the alteration in the conducting states of Q1 and Q2, will be (2V/15)A, which is nearly twice as large.

The increase in available output power from similar output tubes when operated at the same V+ line voltage in a push-pull, rather than in a single-ended, layout is the major advantage of this arrangement, although if the output devices have similar distortion characteristics, and the output transformer is well made, the even harmonic distortion components will tend to cancel. Also, the magnetization of the core of the output transformer due to the tube anode currents flowing in the two halves of the primary winding will be substantially reduced, because the induced fields will be in opposition.

In addition, an increase in the drive voltage to the grids of the output tubes, provided that it is not large enough to drive them into grid current, will, by reducing their equivalent series resistance (R1, R3 in the calculations above), increase the available output power, whereas in the single-ended layout the dynamic drive current cannot be increased beyond twice the quiescent level without running into waveform clipping.

However, there are other problems, which are discussed below.

Phase Splitters

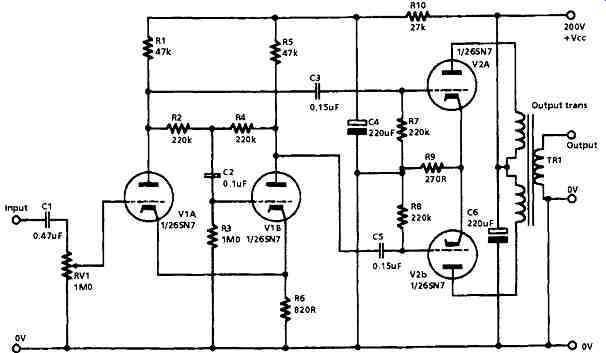

In order to drive a pair of output tubes in push-pull it is necessary to generate a pair of AC control grid drive voltages which are equal in magnitude but in phase opposition. The simplest way of doing this is to use a transformer as the anode load for an amplifier stage, as shown in FIG. 4c, but with a center-tapped secondary winding.

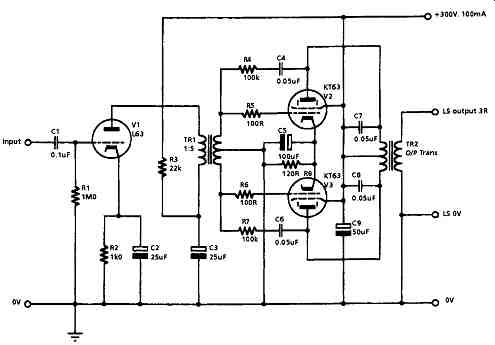

I have shown in FIG. 4 a typical center-tapped transformer coupled 20 watt audio amplifier, of the kind which would have been common in the period spanning the late 1930s to early 1940s. Because there are two coupling transformers in the signal path from the input and the LS output, which would cause substantial phase shifts at the ends of the audio spectrum, it would be impractical to try to clean up the amplifier's relatively poor performance by applying overall negative feedback (from the LS output to V 1 cathode) to the system.

Some local negative feedback from anodes to grids in V2 and V3 is applied by way of C4/R4 and C6/R7 in an attempt to reduce the third, and other odd-order, harmonic distortion components generated by the output tubes. Since the designer expected that the output sound quality could still be somewhat shrill, a pair of 0.05uF capacitors, C7 and C8, have been added across the two halves of the output transformer primary windings to reduce the high frequency performance. These would also have the effect of lessening the tendency of the output tubes to flash over if the amplifier was driven into an open-circuited LS load- an endemic problem in designs without the benefit of overall negative feedback to stabilize the output voltage.

The anode voltage decoupling circuit (R3,C3), shown in FIG. 4, is essential to prevent the spurious signal voltages from the +V supply line to the output tubes being introduced to the output tube grid circuits. This would, in the absence of the supply line decoupling circuit, cause the amplifier to oscillate continuously at some low frequency- a problem which was called motor-boating, from the sound produced in the loudspeakers.

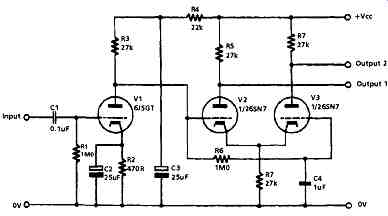

Various circuit arrangements have been proposed as a means of generating a pair of low distortion, low phase shift, push-pull drive voltages. Of these, the phase inverter circuit of FIG. 5 is the simplest, but does not offer a very high quality performance.

It is, in principle, a bad thing to attenuate and then to amplify again, as is done in this arrangement, because this simply adds just another increment of waveform distortion, due to V2, to that contributed by V1.

A much more satisfactory arrangement is that shown in FIG. 6, in which V2 is operated as an anode follower, which like the cathode follower, employs 100% negative feedback, though in this case derived from the anode. This stage contributes very little waveform distortion. Also, because both tubes operate as normal amplifier stages, the available voltage from either output point will be largely unaffected by the operation of the circuit. An additional advantage over the circuit shown in FIG. 5 is that the two antiphase output voltages are equal in magnitude, without the need to adjust the preset gain control, RV1.

FIG. 4 Simple 20 watt amplifier

Another satisfactory circuit is that based on the long-tailed pair layout, in which, provided that the tail resistor is large in relation to the cathode source resistance (1/gm), the two antiphase anode currents will be closely similar in magnitude. The advantage of this circuit is that it can be direct coupled (i.e. without the need for a DC blocking coupling capacitor) to the output of the preceding stage, and this minimizes circuit phase shifts, especially at the LF end of the pass-band. By comparison with the two preceding phase-splitter circuits, it has the disadvantage that the available AC output swing, at either anode, is greatly reduced by the fact that the cathode voltages of V2 and V3 are considerably positive in relation to the 0V line, and this will almost certainly require an additional amplifier stage between its output and the input of any succeeding triode or beam-tetrode output stage.

FIG. 6 Floating para-phase circuit

Fig. 7 Long-tailed pair circuit

This disadvantage is shared by the circuit layout shown in FIG. 8, in which a direct coupled triode amplifier is operated with identical value resistive loads in both its anode and cathode circuits. Because of the very high level of negative feedback due to the cathode resistor both the distortion and the unwanted phase shifts introduced by this stage are very low. Significantly, this was the type of phase splitter adopted by D.T.N. Williamson in his classic 15 watt audio amplifier design.

FIG. 8 Split load phase splitter

Output Stages

The basic choice of output tube will lie between a triode, a beam-tetrode or a pentode.

If large output powers are required--say, in excess of 2 watts- triode output tubes are unsuitable because the physical spacing between control grid and anode must be small, and the grid mesh must be relatively widely spaced, in order to achieve a low anode current resistance and a high practicable anode current level. This closely packed type of construction will lead to the almost complete stripping of the space charge from the region between the cathode and the grid. Experience shows that the life expectancy of cathodes operated under such conditions is short, and the only way by which this problem can be avoided is by the use of a directly heated (filament type) cathode construction, which is much more prolific as a source of electrons, and this leads to other difficulties such as hum intrusion from the AC heater supplies, and the awkwardness of arranging cathode bias systems.

So, if it is required to use a triode output stage, at anything greater than the 50mA anode current obtainable from a parallel connected 6N7 double triode (the 6SN7 has a smaller envelope and, in consequence, a lower permissible anode dissipation), a directly heated tube such as the, now long obsolete, 6B4 or PX25 would need to be found. Therefore, in practice, the choice for output tubes will be between output beam-tetrodes or pentodes. Although a fairly close simulation of a triode characteristic can be obtained in both of these tube types if the anode and G2 are connected together, this approach works better with a beam-tetrode than a power output pentode because the presence of the suppressor grid in the pentode somewhat disturbs the anode current flow.

The required grid drive voltage for typical pentode or beam-tetrode output tubes, at Va = 300V, will be in the range 20-50Vp-p for each output tube, and whether or not the tube is triode connected has little effect on this requirement. Triode connection does, however, greatly affect the anode current impedance, which is reduced, in the case of the KT88, from 12k-ohm to 670-ohm and the need for a lower turns ratio greatly simplifies the design of the necessary, load-matching, output transformer with low half-primary to half-primary and primary to secondary leakage inductances.

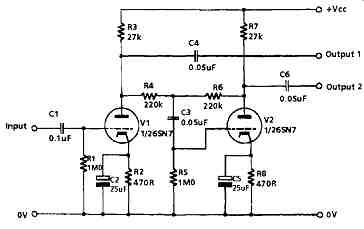

Output (Load-matching) Transformer

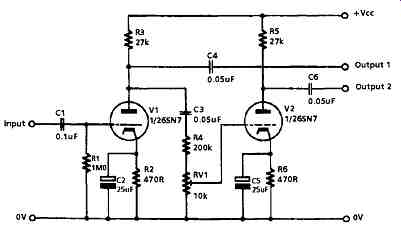

This component is probably the most important factor in determining the quality of the sound given by a tube operated audio amplifier and the performance of this component is influenced by a number of factors, both mechanical and electrical, which will become of critical importance if an attempt is made to apply negative feedback (NFB) over the whole amplifier. However, for a low power system, such as might be used as a headphone amplifier, it is possible to make a quite decent sounding system without the need for much in the way of exotic components, circuit complexity or very high quality output impedance-matching transformers, and I have sketched out in FIG. 9 a typical circuit for a two tube, 1 W, headphone amplifier based on a pair of 6SN7s or equivalents.

FIG. 9 Simple headphone amplifier

In this design the input pair of tubes acts as a floating paraphase phase-splitter circuit, which provides the drive for the output tubes. Since the cathode currents from the two input tubes are substantially identical, but opposite in phase, it is unnecessary to provide a cathode bypass capacitor to avoid loss of stage gain. Also, since this cathode resistor is common to both tubes, it assists in reducing any differences between the two output signals, because the arrangement acts, in part, as a long-tailed pair circuit.

Since the total harmonic distortion from a push-pull pair of triodes will probably be less than 0.5%, and will decrease as the output power is reduced, provided a reasonable quality output transformer is used, I have not included any overall NFB, and this avoids any likely instability problems. To match the output impedances of V2A and V2B to a notional load impedance of 100-ohm a transformer turns ratio, from total primary to secondary, of 12:1 is required.

In more ambitious systems, in which NFB is used to improve the performance of the amplifier and reduce the distortion introduced by the output transformer, much more care is needed in the design of the circuit. In particular, the phase shifts in the signal which are introduced by the output transformer become very important if a voltage is to be derived from its output, and fed back in antiphase to the input of the amplifier, in that to avoid instability the total phase angle within the feedback loop must not exceed 180 degrees at any frequency at which the loop gain is greater than unity. This requirement can be met by both limiting the amount of NFB which is applied, which would, of course, limit its effectiveness, and by controlling the gain/frequency characteristics of the system.

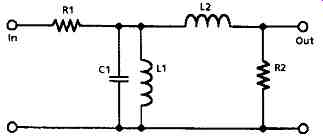

Although there are a number of factors which determine the phase shifts within the transformer, the two most important are the inductance of the primary winding and the leakage inductance between primary and secondary, and a simple analysis of this problem, based on an idealized, loss-free transformer, can be made by reference to FIG. 10. In this, R1 is the effective input resistance seen by the transformer, made up of the anode current resistance of the tube, in parallel with the effective load resistance, and L1 is the inductance of the transformer primary winding. When the signal frequency is lowered, a frequency will be reached at which there will be an attenuation of 3dB and a phase shift of 60 degrees This will occur when R1 = jWL1, where m is the frequency in radians/sec.

FIG. 10 Equivalent circuits of idealized coupling transformer

R2 is the secondary load resistance, which is the sum of the resistance reflected through the transformer and the anode resistance, and L2 is the primary leakage inductance- a term which denotes the lack of total inductive coupling between the primary and secondary windings - which behaves like an inductance between the output and the load, and introduces an attenuation, and associated phase shift, at the HF end of the passband. The HF -3dB gain point, at which the phase shift will be 60 degrees will occur at a frequency at which R2 = jωL2.

To see what these figures mean, consider the case of a 15D resistive load, driven by a triode connected KT66 which has an anode current resistance of 1000 ohms. Let us assume that, in order to achieve a low anode current distortion figure, it has been decided to provide an anode load of 5000 ohms. The turns ratio required will be √(5000/15) = 18.25:1 and the effective input resistance (R1) due to the output load reflected through the transformer will be 833 ohms. If it is decided that the transformer shall have an LF-3dB point at 10Hz, then the primary inductance would need to be 833/2 π 10 = 833/62.8 = 13.26H. If it is also decided that the HF -3dB point is to be 50kHz, then the leakage inductance must be 833/2 π 50,000 = 2.7mH. The interesting feature here is that if an output pentode is used, which has a much higher value of R_a than a triode, not only will a higher primary inductance be required, but the leakage inductance can also be higher for the same HF phase error.

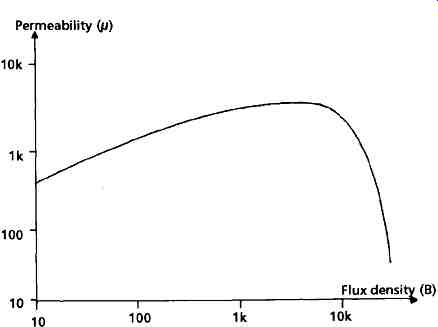

Unfortunately, there are a number of other factors which affect the performance of the transformer. The first of these is the dependence of the permeability of the core material on the magnetizing flux density, as I have shown in FIG. 11. Since the current through the windings in any audio application is continually changing, so therefore is the permeability -- and with it the winding inductances and the phase errors introduced into the feedback loop. Williamson urged that, for good LF stability, the value of permeability, μ, for low values of B should be used for primary inductance calculations.

Secondly, this change in inductance, as a function of current in the windings, is a source of transformer waveform distortion, as are -- especially at high frequencies -- the magnetic hysteresis of the core material and the eddy current losses in the core.

These problems are exacerbated by the inevitable DC resistance of the windings, and provide another reason, in addition to that of improved efficiency, for keeping the winding resistance as low as possible.

The third problem is that the permeability of the core material falls dramatically, as seen in FIG. 11, if the magnetization force exceeds some effective core saturation level. This means that the cross-sectional area of the core (and the size and weight of the transformer) must be adequate if a distortion generating collapse in the transformer output voltage is not to occur at high signal levels. The calculations here are essentially the same as those made to determine the minimum turns per volt figure permissible for the windings of a power transformer. In practical terms, the requirements of high primary inductance and low leakage inductance are conflicting, and require that the primary winding is divided into a number of sections between which portions of the secondary winding are interleaved.

Williamson proposed that eight secondary segments should be placed in the gaps left between ten primary windings. This increases the stray capacitance, C1, across the primary winding and between primary and secondary coils. However, the HF phase errors introduced by these will probably be unimportant within the design frequency spectrum.

FIG. 12a Power output vs. THD. Power output (watts). KT66 Va = Vg2 = 400V U/L

connected

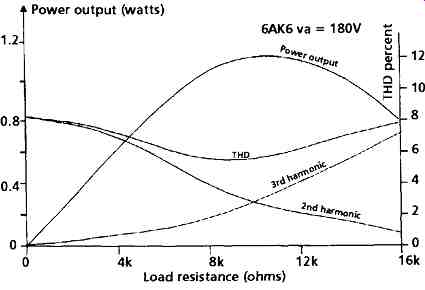

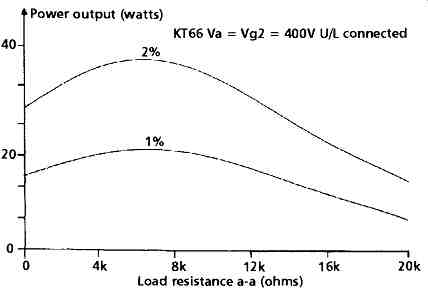

Effect of Output Load Impedance

This is yet another area in which there is a conflict in design requirements, between output power and output stage distortion. In FIG. 12a, I have shown the output power given for 1% and 2% THD values by a push-pull pair of U/L connected KT88s in relation to the anode to anode load impedance chosen by the designer. This data is by courtesy of the GEC (Audio Amplifier Design, 1957, p. 41). Since the distortion can also alter in its form as a function of load impedance, I have shown in FIG. 12b the way these circuit characteristics change as the load resistance changes. The figures given for an single-ended 6AK6 output pentode are due to Langford-Smith (Radio Designers Handbook, 4th Edition, 1954, p. 566).

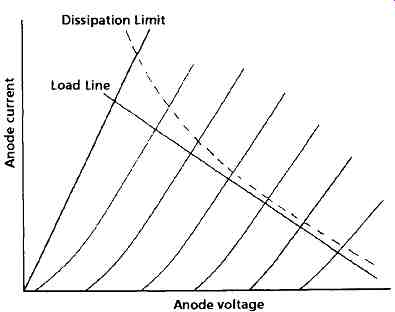

FIG. 13 Anode dissipation curve

Available Output Power

The power available from an audio amplifier, for a given THD figure, is an important aspect of the design. Although there are a number of factors which will influence this, such as the maximum permitted anode voltage or the maximum allowable cathode current, the first of these which must be considered is the permissible thermal dissipation of the anode of the tube. These limiting values will be quoted in the manufacturers' handbooks, and from these it is possible to draw a graph of the kind I have shown in FIG. 13, where the maximum permitted combinations of anode current and anode voltage result in the curved (dashed) line indicate the dissipation limits for the tube, and the load line for its particular operating conditions can then be superimposed on this graph to confirm that the proposed working conditions will be within these thermal limits.