Electrostatic loudspeakers in their various manifestations have been around the hi-fi scene for a long time and have held a peculiar fascination for many audiophiles. Such speakers have always been admired for their clean, open sound; low distortion, transparency and, above all, their lightning-fast transient response. Many people fail to realize that music primarily consists of transient sounds, and therefore accurate reproduction of such transients is of paramount importance.

Many audiophiles have been aware that the desirable attributes of electrostatic loudspeakers are usually offset by many basic problems inherent in this design. Fragility of the thin film of the speaker diaphragm, especially before the advent of Mylar, causes frequent failure due to discrete arcing when overdriven. Efficiency is low, dynamic range restricted, and in those speakers which are supposed to be "full-range" units, bass response usually falls off rapidly below 50 Hz. Added to this is the difficult capacitive load these speakers present to the amplifier.

Despite all of these problems, many audiophiles have continued to admire the special qualities of electrostatic loudspeakers. New models are a fairly rare occurrence in comparison to the never-ending flow of dynamic speakers to the hi-fi market. Hence the hearty welcome to the new Quad ESL-63 and several new electrostatic loudspeakers from the Acoustat Corp. of Fort Lauderdale.

Acoustat introduced its first electrostatic loudspeaker, Model X, in 1976. In recognition of the fact that all electrostatic loudspeakers present a highly capacitive load to an amplifier, the Model X had its own built-in direct-drive, solid-state/ tube hybrid amplifier. The tubed output stage of the amplifier mated well with the capacitive load, but there were some problems associated with this unit. Of course, the basic idea of the built-in drive amplifier was to eliminate the input transformer that is common to all other electrostatic loudspeakers. The transformer is a source of various nonlinearities and exhibits other undesirable properties. While Acoustat had some technical problems with the drive amplifier, a more difficult problem was that most audiophiles already had their own amplifiers and resented the fact that they could not use them to power this electrostatic speaker. Thus, after considerable research, in 1980 Acoustat introduced the MK-121 Magne-Kinetic Interface passive drive system. This device (previously described in my May 1981 column) essentially is a "bi-former" design. Two specially optimized transformers cooperatively "overlap" at about 1 500 Hz and handle the midrange frequencies, while one of the two handles bass frequencies and the other one, treble frequencies. Acoustat calls the MK-121 "revolutionary" and claims it is a near-perfect power/impedance match. Efficiency is very high and impedance is rated at 4 ohms and is claimed never to drop below 3 ohms.

The design is said to eliminate the spurious resonances and "ringing" of conventional transformers. With the MK-121 Interface, all solid-state and tube amplifiers can be used to drive Acoustat ES systems, and since most amplifiers deliver more power at 4 ohms, this is an added bonus.

The current Acoustat Models Two, Three and Four all use the same electrostatic panels. Acoustat hand-makes these panels in their Florida plant.

Sheathed conductor grids are chemically welded to extremely rigid "honeycomb" plastic panels. Sandwiched between the grids is the conductive Mylar diaphragm, only 0.00065-inch thick with an equivalent mass of 7 mm of air! The MK-121 Interface accepts the incoming audio signals from a power amplifier, routes them through the special transformers, and thence to the wire grids. A bias transformer imparts a static charge to the conductive Mylar diaphragm. This grid "sandwich" permits true push-pull piston action over the entire surface of the diaphragm. The result is audio output with extremely low distortion and ultra-fast transient response.

The electrostatic panels on the Models Two, Three and Four differ only in their number, with Acoustat claiming exceptional uniformity and consistency of performance.

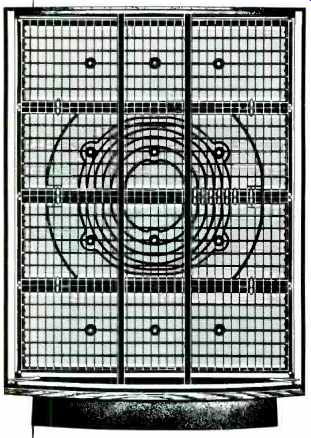

I have had the pleasure of living with the Acoustat Model Four for some months now. This is the largest of the Acoustat electrostatic speakers, standing 59 inches high by 28 inches wide by 3 1/2 inches deep. It has four of the electrostatic panels, the outer two panels being 9 inches wide and the inner two being 8 inches wide. The idea of the different widths is to stagger the individual resonances of the panels to avoid any possible reinforcement of a particular frequency. Two criticisms often directed at electrostatic speakers are their marginal bass response and their inability to reproduce music at high loudness levels.

The Model Four's frequency response is listed at 28 Hz to 20 kHz, ±2 dB. The speaker is said to be capable of an output of 115 dB SPL at 22 feet in a 16 x 26-foot room on program peaks. I have been driving the Model Four with a Levinson ML-3 200-watt power amplifier and have played many recordings with substantial bass response, including my own Virgil Fox organ recording which has pedal frequencies below 20 Hz.

While the Model Four cannot reproduce fundamentals of such low frequencies, it acquitted itself quite well with clean, smooth bass response down to 35 to 40 Hz. With heavy bass drum strokes and lower pitched tympani, the sound from these instruments was very clean, well defined, and of considerable impact. I am not saying that the bass response was of the full-blown, high-energy level available from a good subwoofer, such as that made by Janis Audio. (Incidentally, the Janis W-1 mates especially well with the Model Four if you are inclined to augment its bass response.) As for high-level playback, the Model Four meets its published specifications, and then some. Certainly in the average domestic listening situation, there is more output available than most music lovers would accept. The Model Four does quite well in coping with wide dynamic range, but when I hooked up a JVC 16-bit recording system for direct digital playback, there were some distressful sounds! Like all of the Acoustat speakers, the Model Four is a dipole radiator. I have used them positioned well away from a paneled wall, with good results as to imaging and depth, but when I placed them in my Sonex-treated "live end / dead end" listening room, the absorption of the back wave was quite an aid.

Such treatment with this sound absorber removes most first-order reflections and damps the back wave, so with no reflections arriving later in time, there is a dramatic increase in imaging and depth perception as well as more precise localization of orchestral instruments. Speaking of secondary arrival times, the panels of the Model Four are slightly curved (six degrees of arc), but the total displacement from a plane is less than an inch and therefore arrival times from all four panels are substantially the same.

The Acoustat Model Four is a mercilessly revealing speaker. It really is a reflection of the old computer adage "garbage in garbage out." Play some analog or digital master tapes and the Model Four can give you gloriously realistic sound. Play some really high-quality records and your ear will delight in the clean, smooth response and incomparable transient attack and accuracy. But play some poor recording with "crackly" scratched surfaces, and the Model Four will give you a mirror image of this sonic horror. It should also be noted that in addition to the Model Four's clinical view of program material, it can be equally devastating in showing up poor quality links in the entire chain of reproduction. Try to use an inferior phono cartridge, for example, and the resulting screechy first violins in a symphony recording will cut your ears off! With fine recordings, the Model Four can reproduce violins with that magical sheen and airy transparency so sought after by the dedicated audiophile. Play something like the Sheffield drum record or M&K's Hot Stix, and the revelation of transient attack capabilities will help you understand what all the fuss is about.

I should mention that since Acoustat introduced the Models Two, Three and Four, there have been some worthwhile updates and modifications. The necessary parts, including a newer type of bias transformer, and the substitution of polystyrene and polypropylene caps for the original types, come in kit form and are available for $65.00. The modifications provide about a 1.5-dB increase in output, tighter low bass response, smoother midrange and top end, and even less distortion. These modifications were installed on the Model Fours which I have, and it does indeed make a fine speaker even better. There are no protection circuits in these speakers. Acoustat claims the panels are virtually "indestructible," and with more than 24,000 panels in the field, they have never had a failure! I can sum up my impression of the Acoustat Model Four by stating that it combines the near-legendary performance values of electrostatic loudspeakers while eliminating most of the drawbacks and establishing a very high standard of reliability.

From JVC comes word of an important new development. Would you believe a digital audio cassette recorder? It looks very much like our conventional analog units, but JVC has come up with a very high density (46.3k BPI) recording system to make this machine a reality.

The cassette is the same size as our present audio cassette, and it uses metal tape. However, I have a feeling this tape is of the metal evaporated type. Tape speed is higher, at 7.1 cm per second.

Evidently the PCM recording and playback is via new LSI (large scale integrated) chips. Quantization is "equivalent to 14 bits," and sampling rate is at the rather odd figure of 33.6k per second.

Perhaps this was chosen with an eye to the future when a machine like this might be used with some of the European digital broadcast systems which use 32k sampling rates. Recording time is 30 minutes per side. On this tiny cassette tape width, four tracks for each channel are provided! One is a service track which permits random access, program indication, etc.; the other tracks are for data and error correction. The unit has an erase head and a combination record/play head. The tape transport is a direct-drive capstan system with a newly developed tape-tension servo system. Most significantly, JVC is emphasizing the use of prerecorded digital cassettes for this unit, and in fact, they have developed a high-speed duplicating system for such recordings. (JVC currently has a metal-particle tape duplication system for analog prerecorded tapes.) The new JVC digital cassette recorder is slated to become available in late 1982 or early 1983. As you might expect, pricing is not yet finalized, but an educated guess would be "somewhere between $2000 and $2500." This new system is expected to be demonstrated at the AES Convention at the Waldorf in New York and possibly at the CES in Las Vegas. We'll keep you posted. (Editor's Note: Pioneer and Sony showed basically similar units during the. Japan Audio Fair in Tokyo; both use the Philips-type cassette, like JVC, but coding systems will be different for each of the three machines. While coding systems would have to be an object of standardization, the introduction and widespread use of particular A/D and D/A chips, which are only now being developed, seems to be the main stumbling block to production of single-unit digital audio recorders.

Sony reports they are currently experiencing upwards of 70 percent success in making such chips.

-E.P.

-----------

(Adapted from: Audio magazine, Jan. 1982; Bert Whyte )

= = = =