GIVING RECORDS THE BRUSH-OFF

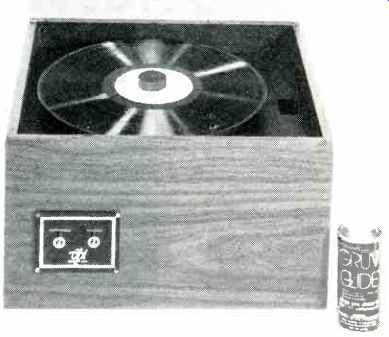

above: Pristine surfaces result from treatment with the HW-16 cleaning machine

followed by Gruv-Glide.

This month some brief reports on diverse items of audio equipment which I have found to be particularly interesting and worthwhile.

The vinyl phonograph record can be a wondrous thing. If the requisite tender loving care has been applied in the plating and pressing processes and the vinyl is virgin and of unquestioned purity, one can enjoy rock or Rachmaninoff from immaculate record surfaces, blissfully free of the snaps, crackles, pops and other extraneous noises that plague record playback.

Unfortunately, the vinyl record is also an extremely fragile thing. The vinyl is relatively soft and is particularly prone to the generation of electrostatic charges. This attracts dirt and dust, which is deposited into the record grooves. To make matters worse, even at a tracking force of one gram, enormous instantaneous pressure and heat are generated at the stylus tip and the dust is ground into and welded to the record grooves. Surely, no thinking person handles records so carelessly that they are covered with oily, dust catching fingerprints. However, people do leave records on turntables after playback, where dust can settle on them. Even the mere act of withdrawing and replacing the record in its protective sleeve can induce static charges. Cigarette smokers create their own particular problems. Some years ago, the late Percy Wilson of that venerable British journal "The Gramophone" made a series of studies which showed that fly ash produced by cigarette smoke was readily attracted by static charges on records. He also noted that heavy smokers created enough smoke so that various tars and other contaminants were deposited on vinyl records. From these studies, the well-known Keith Monks record-cleaning machine evolved. The efficacy of Keith Monks machines have been well documented and many of them are in use throughout the world. However, the high price of the Keith Monks cleaner has made it an item more for institutional and commercial use than for audio consumers. An "economy" model of the Keith Monks cleaner was introduced, but at $995.00 it is still beyond the reach of most audiophiles.

The average audiophile appears to be fairly conscientious in caring for his records, a fact which has produced a myriad of commercial record-cleaning and anti-static devices and chemical agents. Many of these products are long on exaggerated claims of efficacy and short on actual results. Some are close to being outright frauds. Most.

merely rearrange the dust, and few indeed are those which are genuinely helpful. The main problem with most of these agents is their tendency to leave sticky residues in the record grooves, thus further exacerbating the dust problem. It also makes the stylus more prone to pick up this amalgam of grunge.

For some months now, I have been enjoying the benefits of immaculately clean records through the use of the HW-16 record-cleaning machine made by VPI Industries of Ozone Park, N.Y. Harry Weissfeld, the entrepreneurial head of VPI, has come up with a device that embodies many of the basic essentials of the Keith Monks machine, albeit in much simplified form. The HW-16 measures 15 1/2 in. W x 14 1/4 in. D x 9 in. H. The cabinet is walnut veneer, and the top cover is of smoked plexiglass. There is a 12-inch turntable platter driven by a very high torque motor at 18 rpm. The turntable spindle is threaded to accept a 1 1/4-inch Lucite hold-down clamp. The turntable is activated by a toggle switch on the front panel of the unit. On the underside of the plexiglass cover is a vacuum suction chamber, and when the lid is in the closed position the chamber is connected to a high-capacity vacuum pump. A four-inch brush with a high density of specially shaped nylon bristles is supplied, as is a plastic squeeze bottle of 25% isopropyl alcohol. When using the HW-16, a record is snugly clamped to the turntable by the threaded Lucite clamp. The brush is saturated with the alcohol (I also dribble a thin stream of alcohol around the middle of the modulated portion of the record) and positioned so that the tips of the bristles engage the grooves in the direction of record travel. The turntable is switched on and the brush held against the record for about 20 seconds. The brush is then removed, the top cover closed, and the vacuum device activated by another front-panel toggle switch. I have found in practice that more efficient removal of the alcohol/dirt sludge can be accomplished by exerting a moderate downward pressure on the cover in the area over the vacuum device. The vacuum is maintained for about 15 seconds, and then both turntable and vacuum are switched off. The record is removed, the brush flushed clean under running water, and the procedure repeated on the other side.

I have found the HW-16 to be an outstanding performer. The record surfaces are microscopically clean and are so pristine they look new! It must be noted that the machine does not attenuate the sounds of scratches or other surface blemishes, but a lot of the crackly, steady-state noise due to dirt in the grooves is substantially reduced.

A few notes on my experiences with this unit. Even though the alcohol solution is on the record surfaces a relatively short time, some slight leaching of ingredients in the vinyl compound which migrate to the surface does occur. This causes a slight increase in "stiction" (stick/slip friction) on the record. This condition can be overcome by a very light application of GruvGlide. It should also be noted that the alcohol cleaning process is not antistatic and in fact induces a moderate charge on the record. Thus, the GruvGlide not only lubricates the grooves but also reduces static on the record.

Alternatively, the freshly cleaned record can be zapped with a Zerostat anti-static pistol. Brand-new records may look great to the naked eye, but the grooves are actually full of record jacket lint, cardboard motes, vinyl shreds and other assorted debris. Run the brand-new record through the HW16 and you'll have a better chance of getting and keeping quiet record surfaces.

Another point is that ethyl alcohol (ethanol) causes less leaching than isopropyl or methanol. To get ethanol of the highest purity, one can buy a quart of 100-proof vodka, which means the fluid is 50% alcohol. Dilute this bottle with a quart of distilled water and the result is a half-gallon of 25% ethanol. The price of the HW-16 is $295.00. Not cheap, but obviously it is a good item for an audio club, or the cost can be shared among several friends with extensive record collections. The HW-16 is simple, efficient and is most highly recommended.

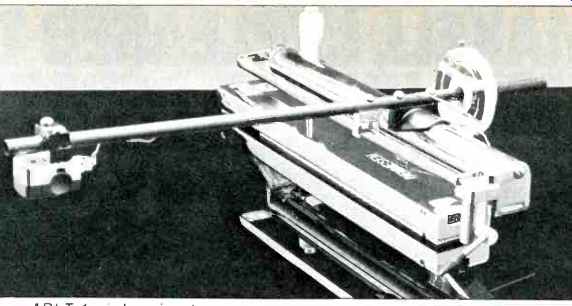

In the July 1982 issue of Audio, my colleague Barney Pisha gave an excellent review of the Dennesen ABLT-1 air-bearing linear tracking tonearm. I am also using one of these remarkable tonearms, and feel that the accolades Barney gave to this arm are fully justified. It is true the Dennesen ABLT-1 is a bit tricky to set up. Overhang adjustment must be precise, and the tone arm must be absolutely level. Satisfy these two parameters, and the air bearing provides the frictionless tracking that permits the arm to operate without lag or deviation from true tangency to the record groove.

above: Dennesen ABLT-1 air-bearing tonearm.

I bring up the Dennesen tonearm because of a particular incident. In my column last month I mentioned Professor van den Hul in connection with the new EMT/van den Hul moving-coil phono cartridge. At the SCES, the Professor had given me a cartridge to try.

At home, I had mounted it in one of the best conventional pivoted tonearms, and during a visit the Professor listened to it and pronounced that I had set it up properly, especially in regard to the all-important azimuth. I was pleased by his comment. However, I remarked that I really wanted to use the cartridge in the spare arm tube of the Dennesen tonearm which I had not yet set up. The Professor promptly called for tiny screwdriver, long-nosed pliers, etc. and proceeded to install the cartridge in the Dennesen arm.

After everything was adjusted we played the same passage from the Mahler Fourth Symphony, at the same level as when the cartridge was in the conventional tonearm. The differences were dramatic. Bass was much fuller and better defined, midrange had more clarity and projection, the treble was smoother, imaging was more precise, and the gain in depth perception was marked. This was a most convincing demonstration of the superiority of the Dennesen air-bearing tonearm. For those who can afford it, this is unquestionably the tonearm of choice.

-----------

(Source: Audio magazine, Nov. 1982; Bert Whyte )

= = = =