Manufacturer's Specifications

Frequency Response: D.c. to 20 kHz, ±0.3 dB.

Harmonic Distortion + Noise: 0.002% at 1 kHz.

Dynamic Range: 100 dB.

Signal-to-Noise Ratio: 115 dB.

Channel Separation: 95 dB at 1 kHz.

Output Voltage: 2.0 V rms.

Number of Programmable Selections: 24.

Dimensions: 17 1/8 in. W x 5 1/2 in. H x 16 1/4 in. D (43.5 cm x 14 cm x 41.3 cm).

Weight: 46 lbs., 3 oz. (19.6 kg).

Price: $2,500.

Company Address: P.O. Box 6600, Buena Park, Cal. 90620.

--------------

The full-function remote has two features useful for speaker testing, A-B repeat and level controls.

Manufacturers of CD players seem intent upon squeezing the very last bit of performance they can out of the 16-bit, 44.1-kHz sampling format that is the world standard for Compact Disc. And indeed, every time the pessimists conclude that nothing more can be done to improve CD player performance, someone comes along with a major innovation to prove that there is still room for improvement, how ever modest it may be in audible terms. Yamaha is the latest company to come up with an important technological innovation, which they call "Hi-Bit Technology." This actually comprises not one but two major refinements, both of which have been incorporated into Yamaha's flagship player, the CDX-5000. This is a "heavyweight" product in more ways than one: It tips the scale at more than 46 pounds, making it heavier than many high-powered amplifiers.

The first technical refinement is the use of a Hi-Bit digital filter. This filter performs quadruple oversampling, raising the standard 44.1-kHz sampling frequency to 176.4 kHz so that a wider buffer zone exists between the top of the audio spectrum and the sampling frequencies. Two benefits immediately accrue. First, a gentler analog filter can be used at the final audio stage without affecting phase response within the audio band. Yamaha is not alone in employing four-times oversampling and digital filtering, but their approach to it is unique here. The digital filter, which oversamples by "filling in" between the actual data samples with three additional data values generated by computation, is an 18-bit, rather than the usual 16-bit, ROM. This is the source of the second benefit: Those two extra bits can reduce quantization-error noise and distortion in the audio band by a factor of four.

The Hi-Bit filter, operating with 32-bit coefficients and a 26-bit accumulator, performs with 40-bit accuracy. There fore, the filter can calculate 192 additions and 192 multiplications for each of the 44,100 CD sample inputs per second, at a clock rate of 16.93 MHz. A total of four 18-bit digital output values is generated for each CD sample.

Yamaha tells me that this entire filter circuit is contained on a single LSI of some 49,000 transistor elements! The second technical refinement, taking full advantage of the first, is the Hi-Bit D/A converter. Since the introduction of CDs, many audio purists have argued that a 16-bit system is inadequate. They reason (correctly, I believe) that when you're dealing with a very loud passage of music-one whose samples are near the top of the available dynamic range-16 bits is enough, but that when the music is at a very low level, 16 bits is not adequate.

Look at it this way: If an actual instantaneous sample is supposed to have a binary number smack between 1111111111111110 (a number whose decimal value is 65,534) and 1111111111111111 (65,535), the error would be 0.5/65,535 at the most! In terms of distortion, this works out to a very low 0.00076% or so. Hardly worth getting excited about. But suppose the music is at a very low level-one that requires only the first couple of binary bits near the bottom of the binary number scale to be changed from zeros to ones. For example, suppose the true value of the musical sample is supposed to be midway between a level of 0000000000001110 (equal to our more familiar decimal value of 14) and 0000000000001111 (decimal equivalent of 15). If we try to define this value, then we have to call it either 14 or 15, when it should be 14.5 (for which we have no available binary equivalent). Now the maximum distortion is quite substantial-0.5/15, or a whopping 3.3%. No won der manufacturers don't quote THD for CD players at low levels. All other things being equal, distortion varies inversely with output level in CD players. If we had more bits per sample, proponents figure, all music, loud and soft, would be shoved farther away from the least significant bit. Add one more bit, and you cut the errors in half; add a second bit, and you cut them down by three-quarters.

The Hi-Bit D/A converters used in Yamaha's CDX-5000 and some of their other new models are "quasi-18-bit" converters. They cannot decode all 18 bits of the digital filter's output at once, but they can match the dynamic range, S/N, arid distortion of true 18-bit decoders most of the time.

The Hi-Bit chip actually decodes just 16 bits at a time. During soft passages, when the two highest (most significant) bits are zero, this D/A converter decodes the lowest 16 bits of the 18-bit filter output. The decoder's action is equivalent to shifting the input digits upward into higher-numbered bit positions, in what is called "floating bit" operation. If the most significant bit is zero, the input bits are shifted up by one position; if the two most significant bits are zero, the input is shifted up two notches.

The instantaneous values of the input samples are there fore made two or four times larger, depending on whether the input was shifted up by one or two bits. If the decoded analog output of the sample has been amplified by a factor of two or four, then that output must be attenuated by the same factor to restore its original amplitude. When this is done, any error in the amplitude (distortion and noise) will be decreased by the same factor. Theoretically, after the entire process has been completed, the reduction in noise will be 6 or 12 dB, and distortion will be reduced to one-half or one-fourth its previous value. These two results are equivalent to those that would be obtained if an actual 18-bit D/A converter had been used; hence the designation of the Yamaha 18-bit converter as "quasi." Naturally, when either or both of the most significant bits are occupied (as during a very loud passage), all the digits must be shifted back where they belong. At the same time, the attenuation that was used in playback to decrease the amplitude of the recovered analog signal to its proper level has to be switched out of the circuit.

Aside from circuitry innovation, the CDX-5000 offers a host of features designed to make use of the player easy, convenient, and reliable. A 44-key remote control permits operation of all functions except drawer open/close, including 20-bit digital volume control. A double-floating suspension system isolates both the disc tray and the laser pickup assembly. The pickup assembly offers extremely high speed access to a given track: Well under 1 S from one track to the next and, by my stopwatch, not much more than that from an outer track to an inner track.

In addition, the CDX-5000 employs a triple-beam laser pickup, dual-transformer shunt-regulated power supplies, discrete circuit configuration, and photo-optical coupling between the digital and analog sections. It features direct-

access programming of up to 24 tracks (or index points), four-way repeat play, random play, and a "calendar" display that shows the numbers of the tracks available on a disc (or in a program) and those that remain to be played.

The unit can be turned on, and play can be started, by means of an external timer.

Control Layout

As you can tell by its weight and dimensions, the CDX 5000 is large and rather bulky. The disc tray, at the left, occupies only a relatively small portion of the front panel.

Beneath the drawer are a "Power" switch and buttons for "Space Insert," "Index," and "Random Play." The display area, to the right of the disc tray, shows track and index numbers, three time modes (elapsed track time, elapsed disc time, or remaining disc time), location of the laser pickup (shown on a ruler-like scale numbered from 1 through 24), operating status of the machine, and, by means of a vertical bar-graph, the setting of the digital volume control.

Under the display area are the buttons needed for pro gram commands, for repeat play, and for altering the display modes. Below these are numbered buttons used in programming and for direct access of tracks and index points. Along the bottom edge of the panel are the "Open/ Close" button and various operating buttons such as "Play," "Pause/Stop," and the fast-forward and fast-reverse keys for moving ahead or backwards to another track or within a given track. The stereo phone jack and a rocker switch for controlling volume level are at the extreme right of the panel.

The rear panel, in addition to its gold-plated output jacks, has a digital output terminal that can be used with external D/A converters.

Measurements

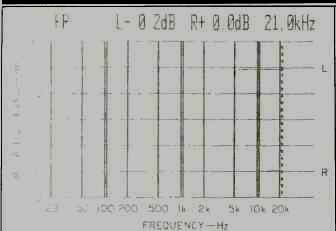

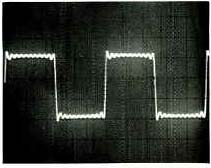

Fig. 1--Frequency response, left (top) and right channels.

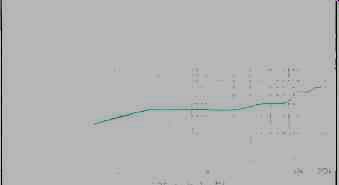

Fig. 2--THD + N vs. frequency.

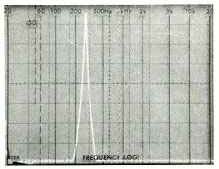

Fig. 3--Spectrum analysis of reproduced 20-kHz test signal from 0 Hz to 50

kHz.

Fig. 4--S N analysis, both unweighted (A) and A-weighted (B).

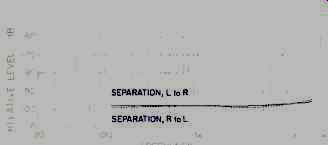

Fig. 5--Separation vs. frequency.

The incremental performance improvements which Yamaha claims for this machine were immediately apparent as I began my lab measurements. As Fig. 1 shows, response was flat right out to 20 kHz, within only-0.2 dB for one channel and with absolutely no roll-off for the other. Harmonic distortion at maximum recorded level at 1 kHz measured 0.0035%. This in itself is not that unusual; what is remark able is the fact that even at 20 kHz, THD + N was only 0.007%, with no low-pass filter of any kind inserted in the measurement path. These results are plotted in Fig. 2. Their significance is further shown in Fig. 3, a spectrum analyzer plot of a 20-kHz signal as reproduced by the CDX-5000.

The sweep is linear and extends from 0 Hz to 50 kHz. The only signal visible is the desired 20-kHz output. Gone is the usual "beat" frequency at 24.1 kHz that has been typical of most CD players-even those that employ oversampling and digital filtering. If there are any spurious products above or within the audio band, it is fair to say that they are at least 80 dB below maximum signal output, since that is the dynamic range of the spectrum analyzer's display. In fact, a reading of 0.007% THD (for the 20-kHz test signal) actually works out to a dB value of-83.1! Figures 4A and 4B show, respectively, unweighted and A weighted signal-to-noise ratio. Overall weighted S/N measured an even 100 dB, and unweighted S/N measured 95.5 dB. Stereo separation was very high too, as shown in Fig. 5.

At mid-frequencies, separation was 98 dB, decreasing only very slightly (to 96 dB from left to right and to 95 dB from right to left) at 16 kHz, the highest frequency in the CD-1 test disc that I use for making these measurements. Dynamic range, measured as THD + N (expressed in dB) for a-60 dB signal, plus 60 dB, added up to exactly 100 dB. Wow and flutter was below the limits of my test equipment.

Further evidence of the benefits derived from Yamaha's Hi-Bit technology came when I measured output linearity. At 90 dB below maximum recorded level, linearity was still accurate to within 0.3 dB. This is the best linearity figure have ever obtained for a CD player. Even the very finest machines usually begin to show departures from linearity at - 70 to- 80 dB. I also measured pre-emphasis/de-emphasis accuracy and found it to be within ±0.3 dB over the frequency range from 125 Hz to 16 kHz. CCIF-IM (twin-tone) distortion was only 0.001% at maximum recorded level and remained almost as low--0.0012%--at-10 dB. Output voltage for maximum recorded level was 2.18 V at the left channel and 2.18 V at the right.

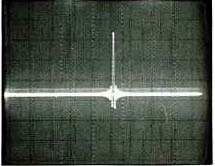

Figure 6 is a 'scope photo of a 1-kHz square wave as reproduced by the CDX-5000. The result is as good as I have observed from any CD player tested to date, and much the same applies to the unit-pulse signal shown in Fig. 7. Both 'scope photos are typical of those obtained from CD players that employ oversampling and digital filtering. In this respect, at least, I could not detect any difference between Yamaha's Hi-Bit digital filter circuitry and the more usual digital filtering employed in other players.

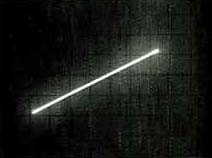

Figure 8 is the Lissajous pattern produced when I fed the 20-kHz output from the left channel to the vertical input terminal of my oscilloscope while the 20-kHz output from the right channel was fed to the horizontal input. No ellipse is visible, indicating that the two output signals are perfectly in phase, with no time delay between them. This is the result I generally get when a CD player employs separate D/A converters for each channel, with timing compensation.

There was no evidence of mistracking and certainly no instances of muting when I played through the three types of defects on my Philips "defects" test disc. The CDX-5000 also did very well with all but the most severely scratched and damaged discs that I keep around for checking tracking ability and for assessing error detection, correction, and interpolation. The sophisticated double-floating suspension system was very effective, making the player extremely resistant to external shock and vibration.

Fig. 6--Reproductior of a 1-kHz square wave.

Fig. 7--Single-pulse tested

Fig. 8--Interchannel phase comparison at 20 kHz. Straight line indicates absence

of interchannel phase error.

Use and Listening Tests

The CDX-5000 is very easy to program and use. The sample in my possession, one of the first available in this country, was supplied without an owner's manual, but that did not in any way slow me down. Nomenclature on the panel is very clear, and it takes only a few minutes to become familiar with all the features and control functions.

As for this player's sound quality, it was, very simply, superb on a wide assortment of discs. If there is anyone out there who still has doubts about CDs and CD players, I earnestly suggest that you listen to the CDX-5000.

If $2,500 is a bit steep for your pocketbook, you might want to listen to Yamaha's CDX-1100, which has a suggested price of just under $1,100. According to Yamaha, this unit is very similar in design to the flagship CDX-5000, using the same Hi-Bit quadruple-oversampling digital filter and the same twin quasi-18-bit D/A converters. Yamaha states that the major differences are a slightly longer access time from innermost to outermost tracks and a single-floating suspension system instead of the double system used in the CDX-5000. (This may account, at least in part, for the fact that the lower priced unit is nearly 15 pounds lighter.) Could I perceive a difference in sound quality between this unit and some of the other well-designed high-end players I have tested? Most of the time, no. Once in a while, a given disc seemed to offer slightly more transparent sound, especially during low-level passages. I particularly looked for such passages so that I might see if the Hi-Bit floating-point D/A converter really cleans up these sounds to the degree that Yamaha claims. In a very few instances, I thought I could hear a difference, a lessening of the "edginess" that I could sometimes detect during quiet musical intervals when I turned up the volume control on my amplifier. The Glenn Gould recording of the Bach "Goldberg Variations" (CBS Masterworks MYK 38479) was one disc in which I could hear an improvement. If you've heard this recording, you know that Gould's low-level murmuring or singing can be heard along with his playing; when I listened to the recording on the CDX-5000, that vocal accompaniment seemed more lifelike than ever, as if Gould were adding his vocal presence right in my listening room.

Admittedly, $2,500 is a lot to spend on any CD player these days, but for some, the extra cost may well be worth it.

At least one will be getting some really new technology and not just upgraded electronics in an old package.

-Leonard Feldman

[adapted from AUDIO magazine, Jan. 1988]

Also see: Link |

Yamaha CDX-11101U CD Player (Equip. Profile, Sept. 1988)

Yamaha CDX-2020 Compact Disc Player (Dec. 1989)

Yamaha CD-X1 Compact Disc Player -- vintage second-generation CD player (Aug. 1984)

Yamaha K-1020 Cassette Deck (Mar. 1986)