Manufacturer's Specifications:

Frequency Response:

4 Hz to 20 kHz, ±0.5 dB.

THD: 0.02% at 1 kHz.

Dynamic Range: 90 dB.

S/N Ratio: 96 dB.

Channel Separation: 83 dB at 1 kHz.

Wow & Flutter: Not measurable.

Number of Programmable Selections: 36.

Line Output Level: 2.0 V.

Power Consumption: 15 watts.

Dimensions: 17 3/8 in. W x 3 3/4 in. H x 10 1/8 in. D (44.2 cm x 9.5 cm x 25.7 cm).

Weight: 8 1/2 lbs. (3.9 kg).

Price: $529.

Company Address: 240 Crossways Park West, Woodbury, N.Y. 11797.

For a while there, it looked as though Compact Disc players would become more and more complicated and offer more and more features (at higher and higher costs). Evidently, Harman/Kardon has elected to return to less complex formats with their HD800. Although its layout is simple, for the most part the HD800 offers all the convenience features users are likely to want or need. Most listeners don't require such fancy operating features as segment or A-B repeat, random program play, and the like.

But with an increasing number of CDs now incorporating index points within a track, being able to access them is important. The Harman/Kardon HD800 can be directed to move to a given index point within a given track but only if that selection is made before play begins. Once the unit has begun playing a disc. the search control--previously used to access index points--now moves the laser pickup assembly ahead rapidly, increasing the search speed if the button is held down for more than a couple of seconds.

In their effort to keep things simple. Harman/Kardon's designers may have gone a bit too far in having just one front-panel control adjust both the line and headphone output levels. I found that normal line output levels required fairly high control settings: for headphone listening, I had to turn the control way down. I think Harman/Kardon would have done better to lower the headphone gain or to provide separate level controls for each output. This minor inconvenience can, however, be forgiven when one considers the relatively low price of this unit.

Control Layout

The uncomplicated panel layout of this unit should prove to be less intimidating to first-time buyers of CD players. The panel is equipper with the usual transport controls (play/ pause, stop, both directions of track skipping, and the aforementioned search buttons). Display, repeat, and programming buttons are found near the multi-display window that shows track number, status (play, pause, program, disc repeat, or program repeat), and three time modes. When the CD tray is first closed with a disc in place, the display shows total time in minutes and seconds as well as the total number of tracks on the disc. When a disc is playing, the display normally shows elapsed time of the track being played. Depressing the "Display" button once shows track and index numbers, and a second push restores the normal elapsed-time display.

The power on/off pushbutton is at the left end of the panel, adjacent to the disc tray. This tray, activated by a nearby open/close button, is ore of the fastest acting I have ever seen. Push the button, and the tray opens before you can lift your finger: the same speed is evident when closing the tray. A headphone jack and the combination phone/line output level control complete the front-panel layout. The panel is finished in matte black, and the nomenclature is a sort of buff color that stands out very well.

All front-panel controls-with the exception of the power switch, the open/close button, and the level control-are repeated on the supplied remote. In addition, there are number keys on the remote, so you can directly access any track on a disc without having to use the skip buttons repeatedly. A pair of AA batteries is supplied for the remote.

Measurements

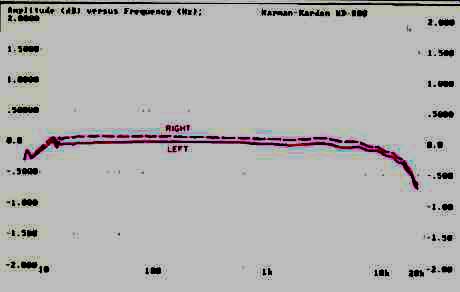

Fig. 1-Frequency response.

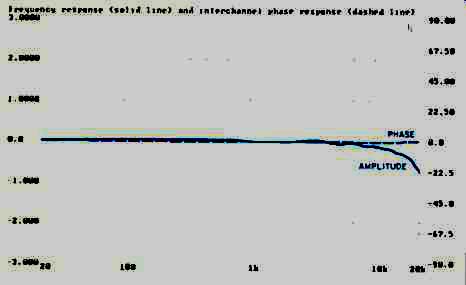

Fig. 2-Comparison between amplitude response of one channel and relative

phase response of opposite channel. Phase, in degrees, can be read from

right-hand scale.

Harman/Kardon did not go overboard in making outrageous performance claims for this CD player. The claimed frequency response of Hz to 20 kHz is accompanied by a tolerance of ±0.5 dB. If one wants to be generous, one could say that the claim is met. The response curve of Fig. 1 never rises above 0 dB, even though it drops to-0.7 dB at 20 kHz. (The upper curve, for the right-channel response, is displaced because of the slight difference in output levels between the two channels.) It's an old audio game to say that this one-way drop of 0.7 dB falls within the rated spec of ±0.5 (or even ± 0.35) dB. Figure 2 repeats the response plot of one channel (solid curve) and adds the interchannel phase response, which was absolutely flat. This suggests that separate D/A converters were used for each channel and that there is accurate time compensation between the two data channels, which are interleaved on the disc's single track.

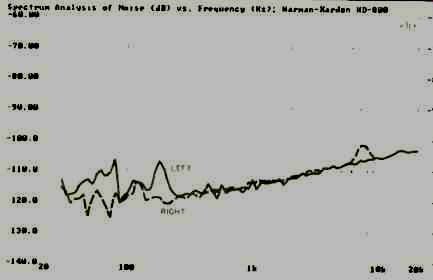

A-weighted S/N, measured while playing the "quiet" track of my CD-1 test disc, was 96.6 dB for the left channel and 95.7 dB for the right. It should be emphasized that this reading represents the S/N of the analog section. The D/A converters are not being exercised when the disc's quiet track, which consists of digital "words" made up of 16 zeros, is played. A spectrum analysis of the residual noise output from that track, as scanned with a Y3-octave filter, is shown in Fig. 3. Unlike what we have seen with a great many CD players that are more expensive, there is very little noise contribution at the power-line frequency of 60 Hz or at its harmonics.

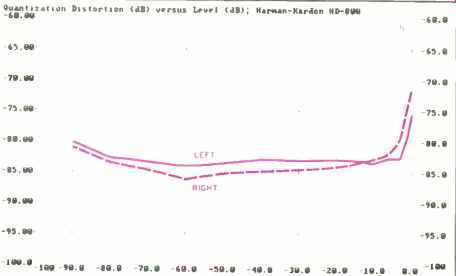

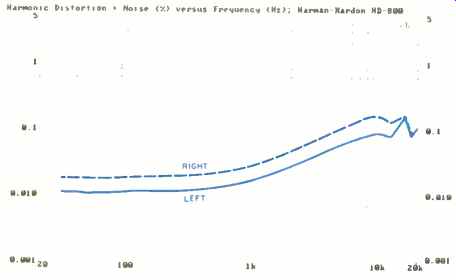

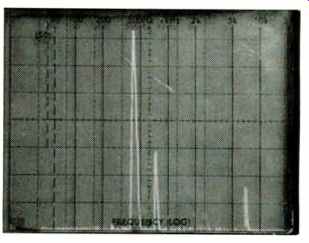

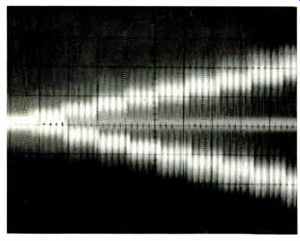

Track 18 of the CD-1 test disc offers 1-kHz signals at various recorded levels, from maximum (0 dB) to 90 dB. A plot of quantization distortion versus recorded level is shown in Fig. 4. Note that the quantization distortion (sometimes referred to as quantization noise) is always referenced to maximum recorded level and is expressed in dB. Quantization distortion remains fairly constant at signal levels from around -5 to-80 dB, but it rises significantly for signals from -5 to 0 dB. This can only be attributed to the beginnings of overload in the system's final analog stages. This explanation is confirmed by the results in Fig. 5, for which I plotted THD + N versus frequency, at a uniform 0-dB recorded level. At 1 kHz, THD + N was 0.0165% for the left channel and 0.027% for the right. Both values are far higher than one would expect if the distortion came solely from the player's 16-bit D/A converters. At higher frequencies, THD + N rises still more, reaching 0.1% at 20 kHz. Confirmation of this rise can be seen in the spectrum analysis in Fig. 6.

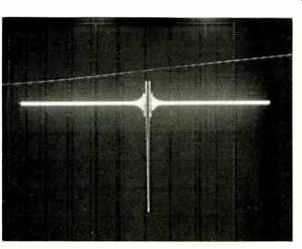

Here, a steady-state, 20-kHz tone, as reproduced from the test disc, was analyzed. The tall spike near the center of the screen is the desired 20-kHz output; the spike immediately to its right is the familiar, 24.1-kHz "beat" often encountered in these analyses and is not truly "harmonic" distortion.

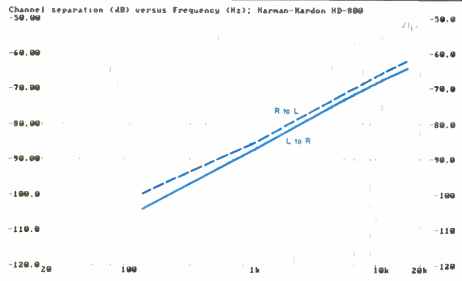

However, further to the right you can see another component. It is the third harmonic of 20 kHz and is about 60 dB lower in amplitude than the 20-kHz signal; 60 dB, expressed in percent, is exactly 0.1%. Figure 7 is a plot of channel separation versus frequency.

At 1 kHz, the unit more than meets its published specification, with separation readings of 87.5 dB from the left to the right channel and 85.5 dB from the right to the left. However, at higher frequencies, separation decreased rapidly.

Though certainly adequate from an audible standpoint, separation at 16 kHz was only 65 dB from the left to the right channel and 62.5 dB from the right to the left. The linear manner in which separation decreased with frequency suggests that the cause of this decrease is in the analog stages. It is more than likely the result of some capacitive coupling between channels-possibly between adjacent wires carrying signals from opposing channels.

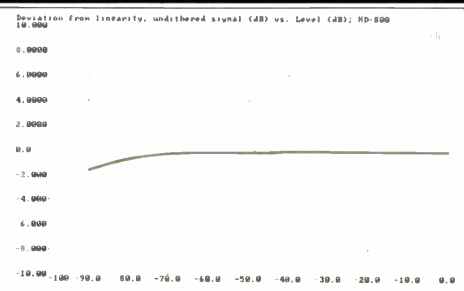

Perhaps the best indication of the quality of a CD player these days is its ability to reproduce low-level signals at their correct relative amplitudes. Any deviation from linearity at low levels must be viewed as a form of distortion. In this regard, the Harman/Kardon HD800 provided a superb example of how the choice of high-quality D/A converter chips can make a difference. Consider Fig. 8, which shows deviation from linearity, measured in dB, from maximum recorded level to -90 dB. At that lowest level, deviation from perfect linearity, using undithered signals, was a fairly insignificant -1.7 dB. This is about the best I have ever measured in any CD player, regardless of price.

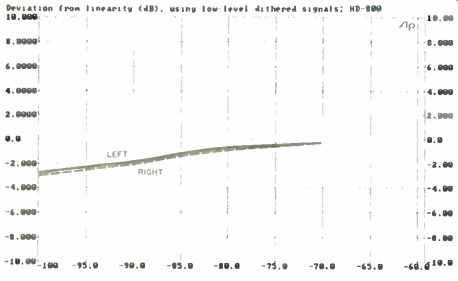

A more meaningful indication of linearity is obtained from Fig. 9. Here, the test signals were dithered and extended from -70 to-100 dB. Even at-100 dB, signals were easily recovered, and deviation from linearity was approximately -3 dB.

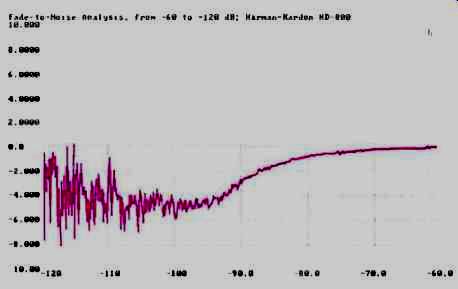

Further confirmation of the excellent linearity of this player was obtained during the "fade-to-noise" test (Fig. 10), in which a gradually decreasing signal from -60 to -120 dB is played through the unit under test. If conditions were ideal, the curve would run straight along the 0-dB line, from-60 right down into the noise level. In this Harman/Kardon unit, signals were still easily separated from the noise (i.e., the noise spikes were within ±3 dB in amplitude) at 100 and even at 110 dB.

Fig. 3-Residual noise vs. frequency for "quiet" track of CD-1

test disc. Note the absence of noise peaks at the 60-Hz power-line frequency

and its harmonics.

Fig. 4-Quantization noise and distortion as a function of recorded level.

Fig. 5-THD + N vs. frequency at 0-dB signal level.

Fig. 6-Spectrum analysis of HD800's output when reproducing 20-kHz signal.

Sweep is linear, from 0 Hz to 50 kHz. Note the "beat" component

at 24.1 kHz and the 60-kHz third harmonic of the 20-kHz test signal.

Fig. 7-Interchannel separation.

Fig. 8-Deviation from perfect linearity for undithered, 1-kHz signal at

levels from 0 to-90 dB.

Fig. 9-Deviation from perfect linearity for dithered, 1-kHz signal at levels

from-70 to-100 dB.

Fig. 10-Deviation from linearity for EIA "fade-to noise" test

of dynamic range, using dithered signal.

Fig. 11-Monotonicity test.

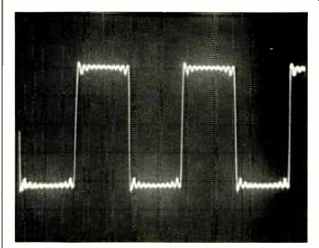

Fig. 12-Reproduction of 1-kHz square wave.

Fig. 13-Single-pulse test.

The monotonicity test on track 21 of the CD-1 provides steadily increasing square-wave signals that start at "digital zero" and increase by 1 LSB after every five cycles, to a maximum of 10 LSB. The averaged steps should, in an ideal situation, show up in the 'scope photo as symmetrical and uniformly increasing above the zero axis and as uniformly decreasing below the zero axis. That is almost the case in Fig. 11, where, upon close examination, you can see that only the very first step shows a bit of asymmetry. All remaining steps are uniform in their incremental positive and negative directions.

The EIAJ dynamic range for this player measured 85.5 dB for the left channel and 87.3 dB for the right; both figures fall somewhat short of the 90 dB claimed by Harman/Kardon.

Clock-frequency accuracy, a factor that determines how accurately musical pitch is reproduced, was off by a negligible-0.015%. Figure 12 shows how a 1-kHz square wave was reproduced by the HD800. The resulting waveform is typical of those obtained from CD players which employ digital filtering and oversampling. Figure 13 shows that the Harman/Kardon HD800 inverts signal polarity; in a noninverting CD player, the signal would appear as a positive going unit pulse.

At long last I have obtained a test disc that taxes the error correction and tracking capabilities of even the most sophisticated Compact Disc players. If you have been reading my test reports for a couple of years, you may remember that I started off with a "defects" disc produced by Philips.

That disc had an opaque "wedge" inscribed on its surface, whose widest dimension was 900 microns (0.9 mm). Many of the earliest players I tested could not traverse the entire wedge without mistracking or, at the very least, getting "hung up" in a spiral, repeating the same instant of music over and over again. After a time, however, more and more players were able to play right through the entire wedge without so much as a single glitch. Eventually, I simply stopped using the disc, as just about every player I tested was immune to the opaque area. I longed for a more meaningful check of error-correction capabilities, but no such test disc was available. Until now! From France came a pair of masterfully produced test discs bearing the Pierre Verany label and distributed in this country by Harmonia Mundi. The discs contain a wide assortment of test signals and also offer a variety of excellent material that is useful for checking out the musicality of any or all parts of a stereo system.

Of particular interest to those who test CD players are the tracking and error-correction tests that go far beyond those of the earlier Philips test CD. One series of recorded signals tests how well a player performs when presented with discs having variations of linear "cutting" velocity. Another series combines variations in velocity with changes in track pitch (the space between two adjacent "spirals"). A third series varies track pitch alone. The tracks which interested me most were those containing various forms of dropouts. I must say that the Harman/Kardon HD800 did as well in these tests as my very best reference CD player. With normal track pitch, there was no audible evidence of mistracking-even for a gap in the data that measured 1,250 microns (1.25 mm). When the HD800 was subjected to test tracks having smaller than normal track pitch, it was able to get through 1-mm wide areas of missing data without any audible discontinuities. The same held true when I played tracks in which there were two such defective areas per disc rotation. The ability of the Harman/Kardon HD800 in this regard goes far beyond the standards required by Philips and Sony of their CD licensees.

Use and Listening Tests

Since the two test discs which provided the extended tracking and error-correction tests also contain a wide variety of musical selections, I decided to use them in my listening tests as well. For those "purists" who believe that no correlation exists between bench measurements and listening tests, let me say that the benefits of the excellent low-level linearity which I had measured on the bench were clearly audible when I listened to music via the HD800 and my reference system. These sonic advantages were especially apparent during quiet passages of a guitar solo and during a clear soprano vocal selection (tracks 4 and 6, respectively, of the first of the two Verany discs). I sensed a clarity of reproduction that I had not heard on Compact Disc players which exhibited poor linearity. To be sure, you have to listen very carefully to hear such subtle differences, but they are nevertheless evident.

The HD800 earns high marks for ease of operation and simple panel layout. And with its high S/N ratio, relatively wide dynamic range, and nearly flat frequency response, the HD800 outperforms many Compact Disc players costing considerably more.

-Leonard Feldman

(Source: Audio magazine, Jan. 1989)

Also see: Link |

Harman Kardon HD7600II CD Player (Feb. 1992)

Harman/Kardon Citation 16 Basic Amplifier (Dec. 1976)

= = = =