Company Address: P.O. Box 2198, Garden Grove, Calif. 92642; 714/554-8200.

by JOHN C. HALLENBORG

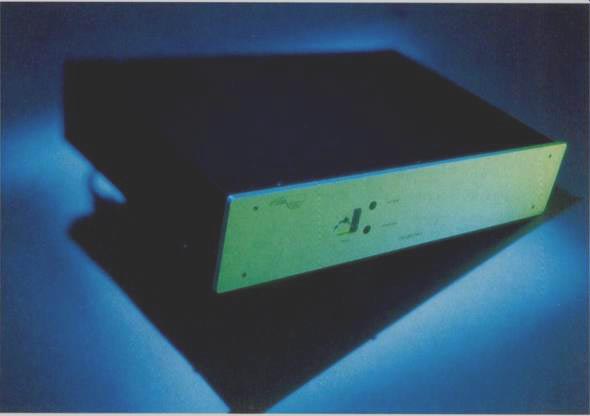

Manufacturers that develop D/A converters and market them in the $1,500 to $2,000 range encounter plenty of competition, as this type of product has for several years been well represented by a welcome selection of such machines. The experienced audiophile has come to expect a lot from these components-sophisticated, beefy power supplies; attractive, well-crafted chassis and faceplates; solid construction; and clean, uncolored sound. Muse Electronics joins the fray with its $1,700 Model Two, a machine with all the above-mentioned qualities and more. Muse, established in 1988, also offers five models of solid-state amplifiers, a solid-state preamp, a new outboard phono stage, and three powered sub-woofers. The company's electronics share a clean look of minimally etched aluminum faceplates in either black or silver; straightforward, heavy-duty well as high-quality jacks, plugs, and switches.

The Model Two D/A converter was designed by two of Muse's top people, who clearly set out to deliver more than a hint of cost-no-object performance at a judicious price.

They have created a very capable machine that includes a few design in construction; as innovations that should successfully differentiate it from the competition.

Internally, the Model Two's circuits are laid out on three p.c. boards, separated from one another to minimize interference. The signal arrives at the digital-filter board through either of two 75-ohm, S/PDIF inputs with BNC connectors.

(An adaptor is provided for standard coaxial connection; a 110-ohm, XLR-connected AES/EBU input is available for $300 and an ST optical input for $200.) The inputs are selected via a three-position toggle switch on the front panel. A blue light indicates that the converter has locked onto the incoming signal (it will accept sampling rates from 32 to 48 kHz). There's no on/off switch and no indication (other than chassis temperature) of whether or not the converter is active until a signal is applied.

Through precision pulse transformers, the signal is passed on to a specialized receiver that uses a phase-locked loop to synchronize to the incoming data stream. Left- and right-channel information is passed along with timing signals to an application-specific processor that provides eight-times oversampling and digital low-pass filtration. (Another $300 option is Pacific Microsonics' digital filter and HDCD decoder chip set, a code cruncher that has gained a considerable following in the months since its introduction. Muse Electronics does not recommend the HDCD alternative, but simply offers it to those who specifically desire it.) The signal is then reconfigured into 20-bit words and sent via a serial data port to the DAC board proper.

The DAC circuit board is the largest of the three and incorporates a number of innovations, some of which are the subject of patent applications. Extremely high-speed differential receivers are used to maintain signal quality. The signal is reclocked in that section, after which a logic circuit attempts to eliminate jitter introduced in the digital-filter stage. From this point on, the circuit is designed to prevent fluctuations in the ground or the power supply from affecting timing accuracy. At the heart of the board are four of Burr-Brown's highly regarded PCM-63K-P DAC chips, one pair for each channel. Each individual chip operates as a 19-bit device, but the pairs are configured to function as 20-bit DACs with excellent linearity around the critical zero-crossing point. Current-to-voltage conversion is achieved in each channel by means of a single resistor ahead of a passive signal-reconstruction filter. The analog output from the reconstruction filter is buffered and amplified by a single gain block that provides both balanced and unbalanced outputs. As delivered from the factory, the Model Two's output from a full-scale digital input is 1 volt-half (6 dB less than) that of most other DACs. So in most systems, the pre-amp should be capable of appreciable gain. The main component of the power-sup ply board is a special multiple-secondary transformer. Power is supplied to the main DAC board through shunt regulators and Class-A (constant-current) sources. Each channel benefits from a dedicated power transformer winding. Power for the input receiver and digital filter comes from separate windings. Supply regulation is provided locally, and power for the front-panel indicators is delivered by discrete driver components. Connection to 115-volt AC service is via an IEC power cord.

For auditioning, I fed the Muse Model Two from a Denon DCD-1015 CD player and from a Forsell CD transport. Other components in my system included a Convergent Audio Signature preamp, a pair of mono amps, and a pair of Brentworth Type loudspeakers. Cables were Kimber Silver throughout.

Fed by the Denon player, the Model Two performed very well, responding predictably to the uneven quality of various CDs. Some of the recordings were produced in the mid-1980s, when few excellent-sounding discs were made. How ever, the latest generation of CDs from audiophile labels (Chesky, Dorian, Clarity, and others) produced bell-like immediacy and robust dynamics. Clearly, all the basic fundamentals were properly reproduced.

On major-label discs, various multi-miking recording techniques were readily discernible. Samuel Barber's Adagio for Strings, with David Zinman conducting the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (Argo 436-288-2 ZH), was characterized by deep soundstaging, harmonic richness, and proper maintenance of separate orchestral sections. Through the Muse Model Two, a fresh performance of Vivaldi's "The Four Seasons," by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra with Gil Shaham (Deutsche Grammophon 439933), set a modern standard for this classic piece. And through the Forsell/Muse combination, Shaham's mastery of both his violin and the music over laid a deliciously woody harmonic texture.

The playback of music for piano is per haps the best simple test of a component's capabilities. On Earl Wild's performance of Rachmaninoffs Variations on Themes of Chopin and Corelli (Chesky CD58), each note was set forth by the Denon/Muse combination with a liquid concentricity that manifested a taste of the real instrument.

Putting the Forsell in the chain improved the effect while adding very subtle ambient cues that I could hear only late at night, when background noise was nearly nonexistent. The Muse could hardly be faulted in going about its business, although some tube-ophiles might prefer the more rounded sound of DACs with vacuum tubes in the output. Such machines tend toward a richer, more forgiving character.

In dissecting the Muse Model Two's sound, I assessed high frequencies by using CDs heavy with cymbals, violins, flutes, and piano. The Chesky brothers somehow get the "nth" degree of shimmer from cymbals in their latest generation of recordings, and the Muse was up to the task of reproducing them; feathery brush strokes, for example, decayed clearly and cleanly into blackness.

In the midrange, Dawn Upshaw's bright portrayals of Canteloube's Songs of the Au vernge, with Kent Nagano leading the Lyon Opera Orchestra (Erato 96559), were free of any stridency or unevenness that might point to deficiencies in the hardware. Can teloube's regional classics were very finely delivered, as Upshaw gives what amounts to a tutorial on singing.

Susannah McCorkle's interpretation of Carlos Jobim's "Waters of March," on From Bessie to Brazil (Concord Jazz CCD-4547), was stunning. So smooth and precise was the sound that it was easy to forget that a collection of resistors, capacitors, and so forth was involved in listening to the Forsell driving the Muse.

Son Seals's Nothing but the Truth (Alligator ALCD-4822) is a no-nonsense blast through the electric heart of modern blues.

It's easy to appreciate his guitar's forte, harmonics, through the Muse, despite the frenetic construction of his songs.

For comparison, I set the Muse Model Two head to head against two more expensive machines: Theta Digital's DS Pro Generation III, a reference unit of a year or two ago, and the Audio Logic Model 34, a single-bit machine that has a tube analog stage. The good news for potential buyers of the Model Two is that there was not much to tell it apart from the Theta, which sold for $4,000 not long ago. The $4,400 Audio Logic had a laid-back quality that some listeners would prefer, and it would do well in systems suffering from two-dimensionality.

Also, the Audio Logic has that tube magic that you either want, need, or consider a euphonic coloration to be avoided.

The Muse Model Two performed flawlessly throughout the audition period-not an unusual occurrence, but one worth noting. It must be considered among the few machines at the forefront of the $2,000 D/A converter offerings. Whatever flaws it might have were so minor that they could well be attributable to the recordings or to gremlins in other parts of the reproduction chain.

Overall, a very nice job by the Muse Electronics crew.

(Audio magazine, Jan. 1996)

Also see:

Museatex Bidat D/A Converter (Equip. Profile, Nov. 1995)

Assemblage DAC-1 D/A Converter Kit (Nov. 1995)

Philips DAC960 D/A converter (Jun. 1988)

= = = =