by TED FOX

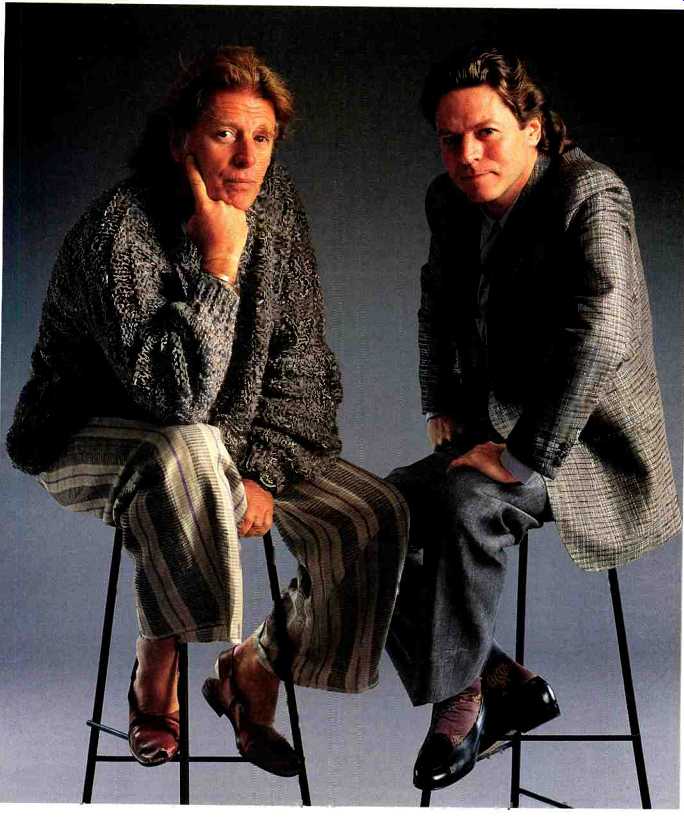

[Chris Blackwell (left) with one of his major artists, Robert Palmer.]

Chris Blackwell is one of the most fascinating figures in the history of the music business. He is both the most modern of men, in terms of taste and technology, and one of the last of the old-fashioned record industry entrepreneurs. His epic career began in Jamaica where, as the sole importer of American rhythm-and-blues records, he provided a unique and invaluable link between the sidewalks of New York and the streets of Trenchtown. Later, in England, he began producing and importing Jamaican ska music and built up his fledgling record company, Island.

After hitting it big with Millie Small's "My Boy Lollipop," Blackwell began signing seminal British rock bands, notably The Spencer Davis Group, which featured 15-year-old Stevie Winwood. When Winwood formed Traffic, he signed with Island. Soon many of the best British bands of the late '60s, such as Jethro Tull, King Crimson, and Emerson, Lake and Palmer, joined the Island roster. Blackwell also inherited the finest of Britain's folk movement, including Fairport Convention and John Martyn.

In 1970 Blackwell helped underwrite the excellent reggae film The Harder They Come starring his artist, Jimmy Cliff. Then came his most important artistic find, Robert Nesta Marley. He became close with Bob Marley and other reggae artists, and almost singlehandedly broke reggae music as an international sensation. Moving his home from Jamaica to Nassau in the Bahamas, he set up the lavish and popular Compass Point Studios.

In the mid-'70s Blackwell signed Roxy Music and then a host of top new artists such as The B-52's, Grace Jones, Robert Palmer, Malcolm McLaren, and U2. He also tried to do for African music-namely the Nigerian phenomenon King Sunny Ade-what he had done for reggae. Now he's moving actively into film. This is Chris Blackwell's first feature-length interview.

-T. F.

What did you do before you were in the music business?

I was in the waterskiing business, teaching waterskiing in Jamaica. I wasn't really doing anything much just hanging out. But I was a very, very keen jazz fan. My jazz interest started at school with boogie-woogie piano re cords-Pine Top Smith, then Jelly Roll Morton, then all the way up through traditional jazz to the contemporary jazz that was being played at the time by Eddie Condon and Wild Bill Davison. I compressed it into about five or six years as my tastes evolved through these different styles of jazz. Then I met Miles Davis in New York, in 1959, when he had his unbelievable band with John Coltrane. I spent some time with Miles, maybe five or six occasions over the course of a year. But they were so burned into my head that I felt I'd spent a year with him.

At the time, that music was on the cutting edge. Your tastes have always seemed to be on the edge.

I was never interested in pop music. I never bought any pop records. The first sort-of pop records I bought were R&B. Even Chuck Berry wasn't my thing. I'd like the odd Little Richard record, but I was never a huge fan of Elvis Presley. The music I always liked was jazz. By definition almost, jazz is on the cutting edge of music, because that's what jazz has always been doing--breaking new ground.

Let's talk about how you got started in the record business.

Before I started making records I used to import them into Jamaica. The first record I made was with this jazz band that played in Jamaica at the Half Moon Hotel. It was led by a jazz pianist, Lance Haywood, who came from Bermuda. He plays in New York now. I liked what he was playing, and I figured that at worst we could make the records and sell them at the hotel. I made the tapes, took them to New York, and got them mastered. I had some artwork designed and the covers made. Then I took the masters to Jamaica and had the covers printed there. I went to the pressing plant and watched them press the records; then I picked them up and took them around to the shops. They didn't buy any hardly any. We also sold some in the hotel. But I just liked the whole process of seeing something all the way through. I made another record with the same artist, adding the brilliant Jamaican guitarist Ernest Ranglin, and it didn't do well either. But I had caught the bug.

It was after that that I found myself in the record business. I'd go to the pressing plant and press up my 250 albums, and I'd see the press next door was for singles. I became very aware that there were lots of singles being pressed, lots more than the al bums. I saw another sort of excitement--the excitement that happens when you have a hit record. It was a whole different thing from the whole process of actually making a record. Then, what I started to do was hang around all the sound systems.

You should explain what the sound systems in Jamaica were. They were basically travelling disc jockey parties, right?

Yes. They were like travelling discos. The sound systems were owned by the various liquor distributors and run by guys called King Edwards, Duke Reid, Sir Coxsone Dodd, Prince Buster--all these characters in Jamaica. So suppose somebody wanted to have a dance. They would book these guys, and they'd come and play. The people would charge admission and these guys would then also supply the liquor.

There became a great competition over who would book which sound system, and which sound system would draw the most people. There'd be sound system wars to see who could get everybody to leave the other's party. These guys would play music through huge boxes of speakers. It was before stereo, but they'd have three or four speakers. It had a very bright treble. You'd hear them from miles away. They still have sound systems in Brooklyn. I was sort of the singular white character hanging out at these. It was a whole sort of nether world. Middle-class black Jamaicans didn't go there, and white people certainly didn't. It was just a Jamaican street thing.

Was this a Rastafarian thing? Or hadn't that come along yet?

Not really. Rasta was there, but it hadn't really evolved as much as it did in the '70s. At this time whoever had the best amps and speakers-and, of course, the best records-would draw people. So what I used to do was come up to New York and buy 78s. I'd buy them for 600 or something, scratch off the label, take them down to Jamaica and sell them for $50. Because if this guy had a hot record and that guy didn't ... it became worth that kind of money. I'd scratch the title off because if they could see the title they could also buy them for 600. So that's how I first started in the record business.

After a bit, the sound system guys and myself, at around the same time, said maybe we should make some re cords ourselves. That is essentially what happened. You'd make the re cord and just release a certain amount on a blank label. A blank label had the same value as it would if it were scratched off. That's how the blank-label thing happened. Obviously, since it was a record made in Jamaica, people would know how to get it, if they knew the title, but making it blank you could charge, let's say, $20 for the first hundred or so. That was called "pre release." Then after a bit you'd release some more, let's say 1,000, at a quarter of that price. Then you'd release it to the general public. Also, around this same time, there became sound systems in England and New York for Jamaicans who had emigrated. So these Jamaican records would be exported, or people would come down and buy a whole pack of the new, key-release records. I was one of the first people in Jamaica to make records for this market. Before that, records made in Jamaica were calypso records, or records made for tourists.

So it was records for the sound systems that you saw when you were at the pressing plant making your Lance Haywood albums?

Yeah. That's where I met these sound system guys. They'd wonder what this white guy was doing in a pressing plant. I got to hang out with them, and they'd say, "Why don't you come along to the sound system?" I discovered the whole nether-world music scene in Jamaica from people I met in a pressing plant. So the next three records I made each went to number one in Jamaica. I thought, "My God, this is unbelievable. This is easy." Then I started to try to make the records better, more polished, more carefully done.

Did you just learn your studio technique as you went along?

Oh, yes. But what happened was that as I tried to make them better and more refined, I started to lose the feel for the market, and my records were now not selling in Jamaica. They were ballad records with people like Jackie Edwards. People would say, "Boy, they're great," but in general they weren't selling. Now and again we'd have one which would sell a good amount. What happened was that in England the import market for them began to pick up until someone contacted me and wanted the rights to press them. So I found that I was, in fact, selling more records in England than I was in Jamaica. Also, the competition in Jamaica had gotten very stiff because lots of people were now making records there; they were basically ska records at that time. So on one trip I made to England, I thought maybe what I should do is start a company there.

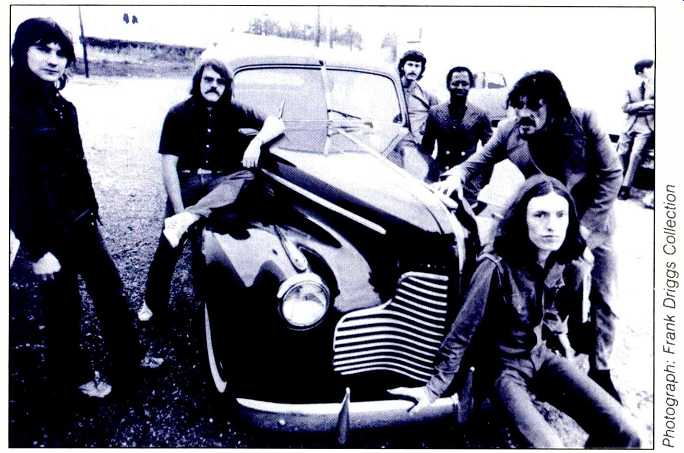

---------- Traffic (above), the band formed by ...

... Steve Winwood (above) after the breakup of The Spencer Davis Group.

I went to all my competitors in Jamaica and said, "Listen, I'm going to start in England." I made deals with all of them, with the exception of Prince Buster, to release their records in En gland. Buster and I never really got on too good. Also, he worked with the guy who owned the main record company in England for Jamaican music--his name was Emile Shallit, and he owned a company named Melodisc which re leased the ska records under a label called Bluebeat. People used to call it bluebeat music. When I started in En gland [with Island Records] I had to get over the fact that I was like a vacuum cleaner company trying to go against Hoover. The generic name for the music was another person's label! So in England we really pushed the name ska music, which is what it was called in Jamaica. We really had to get that across.

But there was no difference between bluebeat and ska?

It was the same thing. The difference was that the artists on the Bluebeat label never went on my label. When I pressed my first record in England, I took it around to the shops. I developed a kind of system of distribution which was essentially me. But it was a very efficient system.

What kind of quantities are we talking about here?

I pressed 500 of the first record in England. It was "Darling Patricia" backed with "Twist Baby," by Owen Grey. I sold out the first day. I pressed some more. I developed a system of going around to each of the shops in London twice a week. I carried my stock in my car, a little Mini Cooper. This was great service for the shops. Here I was with the new releases, then while I was there I'd say, "Well, how about this one? Do you have enough?" I'd make it my duty to be sure that I sold at least as much as what the last order was. I'd be able to do that all the time. I developed a very good relation ship with the shops, and I'd guide them as to what records to buy. If I guided them wrong, I'd take the re cords back and exchange them. There was no actual exchange thing, I just worked it out so they never bought a record from me they couldn't sell. They loved my service. They couldn't lose. This was essentially what I did from May 1962 until the end of '63.

Then you really hit it big.

At the end of 1963 I brought over Millie Small from Jamaica. She had sung on some of these Jamaican records. She sang on one of the first we released, "We'll Meet." It was a boy-and-girl song; the boy sang the first verse and she sang the second. Whenever she came in and sang everybody used to go into fits of laughter because' she has this pipsqueak voice. But every body loved it. So I thought, "I should really bring her over and see what I can do with her in England." Now, be fore I scratched the labels off the 78s I sold, I used to tape them in case I couldn't get a record again. I had a 7 1/2-ips reel of these tunes, and one of them was a song called "My Boy Lollipop." So Millie was over in England and I just happened to be playing this tape of these old records, and I said, "Boy, that's a tune we should record with her." We recorded it and it came out in early '64.

This was really at the height of the girl groups in the United States. Did their popularity make you think that maybe this was a way for a black act to cross over?

Not really. What I thought was that Millie's voice had such a charm to it that you just had to smile when you heard it. Then, when I met her, she had such an engaging personality that I thought we really had a shot with her. In fact, when that record went out, the press really went crazy for Millie. She was a dream for English people. She was an unthreatening little black girl, and they loved her. Her record is what put me in the pop music business. I never even knew what the pop business was.

That record was a smash. Didn't it sell six million copies?

Yes. But I didn't put it on my own label in England because I didn't think I could handle a hit. I licensed it to Phil ips, who released it on a label called Fontana. Then, essentially, I left the whole Jamaican business for a bit. I got drawn into the pop business. See, I managed Millie as well. In fact, I was doing pretty much everything for her. In this period I was concentrating specifically on how to promote her. As she became more successful, I just be came more busy and more into that side of things.

------------ King Crimson, which Blackwell calls "a leap forward

in rock."

You've said you were never really interested in pop music, and all of a sudden you were this pop mogul. Didn't that strike you as odd?

Well, it doesn't happen like that. I was just a guy who produced one pop hit.

My main thing was still Island Records, but I got drawn into this because it was widening one's horizons. It was still essentially the same thing. It was still Jamaican music I was promoting, but it was now becoming a worldwide phenomenon with this particular record. We toured the world, basically.

Do you think people recognized it as Jamaican? I remember when it came out; to me, it was just another neat little pop song.

It was recognized as being Jamaican in England because it was a ska rhythm, although a very polished ska rhythm. I think in America there was no knowledge of the Jamaican music scene at all. Whatever existed would have been very underground, in Brooklyn. Here in America that record would have been classed with some thing by Little Eva, or some other pop singer.

-------

YOU CAN'T EXPECT a major company to send out 200 records; that's exciting for you but not for them. Your job as an independent is to get them interested.

----------

As you were touring with Millie in Birmingham, England, you first heard The Spencer Davis Group, right?

That's right. I went to this club with Millie; she was doing a television show in Birmingham. Somebody told me there were these two bands in Birmingham I should really see. I don't know why this person rang me up, but he did. He was keen on one band and took me to see them first. They were called Carl Wayne and The Vikings.

That band became The Move. I didn't really like them; they were dressed in suits and they were very polished. You know, it was the same era as the early Beatles. They were very "smart" and dressed in suits like the Swinging Blue Jeans or The Hollies. It was good, but it was pop, and I don't really feel straight pop music. Then I went to this other club, and the guy said, "Well, this group draws a lot of people, but they're kind of rough and ready." It was The Spencer Davis Group with 15-year-old Stevie Winwood.

Was he singing when you saw them?

When I walked in, he wasn't singing. Spencer Davis was singing, but it was great. The tune was great, and I really loved that. Then Steve sang and I couldn't believe it. It was like Ray Charles on helium [laughter]. Unbelievable.

Did you approach them right away?

Absolutely. Right then and there. I said I wanted to sign them and make a record with them. These were the days when bands used to go out and play, develop fans, then try and get a record contract. Nowadays people get a re cord contract, buy the instruments, make the record, and then have videos force-fed to the media. These were real people. I was really able to sign them because I promised them that I would be able to get a record out within a month. They were amazed. I produced the first record of theirs and took it to Philips. It was a great tune called "Dimples," a John Lee Hooker song. I was really excited about it. I don't know if you've heard it done by The Spencer Davis Group, but I'm very proud of it. If you hear it right now, it sounds great, like it could have been cut yesterday. I really thought it could be a hit. Then John Lee Hooker decided to tour En gland. He essentially took all the shine off it. We had no hope for our version of the record.

Were there other rock bands you were signing at this time, in '64 or '65?

I'll tell you who I signed in '64--John Martyn. He has a new record that's just come out, so many years later, which is his best. I also signed a band that was so great, a band that slipped through the cracks-they were called The VIPs. They played the Star Club in Hamburg. That's where I first saw them, on tour with The Spencer Davis Group. They were unbelievable. Energy. Drive. Raw. They were the most exciting band. They broke up, then be came a band called Art, then Spooky Tooth. Mike Harrison was their leader. Spooky Tooth was never as good as The VIPs. But The VIPs were impossible to handle and control. I think now, today, having much more experience in putting these things together, what was needed was really to find the right producer and manager for them. What was needed was somebody to spend 24 hours a day with this band and drag out what they had in them. At the time, I was running a record company and managing Millie, and I was just over stretched.

----- Jethro Tull, the first group on the Chrysalis label, an Island spinoff.

What did Philips, to whom you licensed your records, do for you?

They got them on the radio, distributed them nationally, and collected. I would never have been able to collect the money for Millie's hit [on my own].

What does an independent record company look for in a distribution deal with a major company?

It depends. If you're doing just a straightforward distribution deal, what you want is for them to be able to give you the records when you need to get them pressed. Also, they can get re cords into a marketplace when you have some activity in that market place--a band touring, or promotion on the radio. The problem is always in motivating a large distribution company. It's very hard, in the early stages, to get them interested in sending 200 pieces of something somewhere, be cause they're geared up for moving hundreds of thousands. In the early stages, you've got to take the time to get the records into those markets yourself. If you shout and scream and go crazy, it doesn't really help you be cause it means that you're not being sensitive to the facts of how the business is run from their point of view. They can't be expected initially to get that excited about sending 200 re cords somewhere. That's exciting for you, but it's not that exciting for them. Your job as an independent is to get them interested.

When The Spencer Davis Group broke up in '67, Stevie put together Traffic, which became your first big rock act.

Right. I was always worried about Island as a name. If was formed in Jamaica, just after that movie, Island in the Sun. In my head I was always scared--since all our initial records had been Jamaican records--that we would never be able to get over the perception of being an "island music" record company. I tried another name, Aladdin Records, in England. There had been another Aladdin, but it was long gone. That didn't really work. Finally, what I thought I'd do was change the design. I had a pink label and a very pop-image pink sleeve made up. We started using that with Traffic's "Paper Sun," which was Island's first go at being a pop record company.

What happened to your Jamaican stuff at that point?

The Jamaican stuff continued on a different Island label. Actually, at that particular time I drifted away from the Jamaican side. I was really occupied full time with the pop mainstream business. During that time there was a merger with another record company, Trojan Records. Trojan dealt with all the Jamaican stuff, and Island had very, very few Jamaican releases in that period-from about '66 to '69. I got back into Jamaican music with Jimmy Cliff's Wonderful World, Beautiful People in '69.

Was it just automatically assumed that Steve Winwood would stay with Island after the breakup of The Spencer Davis Group?

No. I was also managing Stevie. EMI came up with a really good offer to sign him. I presented him with the offer from EMI, and also said that I felt we could now do it ourselves. We had this kind of P&D [pressing and distribution] arrangement with Philips. We'd evolved from a licensing deal to a P&D deal. So I felt we could now handle it. Steve said he would come on Island.

What was he like as a teenager?

He was pretty wild as a teenager. He was like he is now. When I say wild, I mean full of life, full of zest for living.

Was he sharp in business dealings?

He was never really involved in business dealings because his brother Muff looked after all his business. He's now one of the main directors of CBS Records in England. As soon as The Spencer Davis Group broke up, Muff came to Island running promotion. It was also because of that connection that Steve decided to stay.

We were really the first independent in England to go out and have the trust of the groups as a full-scale record company, as well as just a label. An drew Oldham's Immediate label and Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert's Track label also came out at approximately the same time, but neither of them had the sort of depth of catalog that we did.

They were both just labels. They were in fact very, very good. If those two hadn't sort of disappeared.... They were real talents in the record business. But Traffic became Island's flag ship group, and that enabled us to attract other rock talent, because Steve was the hero of all these guys. He was really adored by them.

After Traffic you went on to sign other great English rock bands of the late '60s such as King Crimson, Jethro Tull, and Emerson, Lake and Palmer. Good musicianship seemed to be the link there. Is that what you were after in those years?

Yeah, musicianship and good singing ability were really important to me. I think that's because, as I said earlier, the records I always liked were jazz records.

Let's talk about King Crimson.

King Crimson had a really spectacular use of sound. Their music would really create images. I think they were a seminal group-a leap forward in rock mu sic. Robert Fripp was a brilliant musician. What also started to happen in music at this time was that more of the well-educated, university-graduate types were coming in as musicians and band members. So you were starting to have a different sort of input into the music. Robert Fripp really represented that new type of performer.

---------- Emerson, Lake and Palmer, "a great group to watch," says

Blackwell.

How did you first hear about the group?

They were just one of the bands that were around that you heard about. They were building a spectacular reputation very quickly. All the different record companies wanted to sign them. Their two managers went to the same school as I did in England, so we sort of got on, on that basis. They were both motorcyclists and I was so deter mined to sign this band that I also bought a motorcycle and nearly killed myself on it, trying to hang out with them [laughter]. But I eventually signed the band, and put down the motorcycle from then on.

How did you find Jethro Tull?

I would have bands touring--Traffic or Spooky Tooth--and they'd come back and I'd say, "Did you play with any bands or see anyone that was interesting?" Gary Wright, who was one of the singers of Spooky Tooth at the time, said, "Oh yeah, we saw this guy who was really great. He was kind of weird, though. He played flute and stood on one leg." That sounded intriguing to me, so I checked it out. I found out they were a new band managed by Terry Ellis, who at the time had a partnership with Chris Wright. So I tracked him down. I made a deal with Terry Ellis.

He wanted to start his own label. I told him that was great, I could really show him how to do it and guide him. He wanted to start it right away with Jethro Tull and I said, "No, that doesn't make any sense. Island is really hot now and our name is strong. It will help Jethro Tull to be on Island. What we'll do is this: When you have five chart entries, records in the top 40--from Jethro Tull or any other acts you bring through on the same deal-we'll start the Chrysalis label. All the acts will then go on Chrysalis." Needless to say, Terry signed some other acts and worked them really hard and got five chart en tries within a matter of a year. Then Chrysalis started and it was with us for about 10 years. Now they are one of our main competitors. Chrysalis kind of outgrew us, and we made a few mis takes. There came a time when we really couldn't be of use to them any more, so they left.

Who else was on Chrysalis at that time?

At the beginning it was just Jethro Tull. Then there was Blodwyn Pig. Ten Years After, who were managed by Chris Wright, were on Decca; they only came to Chrysalis later. A group called Clouds, which never made it. Terry Elis really liked Clouds, spent a fortune on them. But Jethro Tull became a very big band.

Did you ever regret that you didn't keep them for yourself?

Not really. I think it's good for people to grow. If Island grows to contain their growth, that's great. But if they outgrow us, then they should go on.

How about your involvement with Emerson, Lake and Palmer?

They came after King Crimson's demise, which was a disaster for us. There was such great promise with King Crimson. Greg Lake [from King Crimson] and Carl Palmer from Atomic Rooster joined Keith Emerson, who had become a star with a group called The Nice. When ELP first came on the scene, I remember they had a special show for Ahmet [Ertegun, head of Atlantic, which released the group's re cords in North America] and myself at the Lyceum in London. It was great. Did you ever see Emerson, Lake and Palmer? Emerson used to stab the key board with a knife, then lift it up and throw it against the wall. At the end of it Ahmet said, "Boy, that's the first band I've ever seen play with a piano." [Laughter.] They were great at the be ginning.

They were one of the first major bands to use synthesizers. How did you feel about that?

I liked synthesizers from the beginning. I'm very keen on them. I love the new technology in music and everything. Pink Floyd would also have synthesizer sound. But it was never used as Emerson, Lake and Palmer used it--in a sort of cathedral-rock fashion. Emerson, Lake and Palmer had incredible dynamics. Where I fell out with them--and I fell out with them very badly was when they started touring with a big orchestra. I felt that the whole brilliance of ELP was all these different textures and colors of sound which were created just by these three guys on stage. When the audience saw all this sound from three guys, they were really impressed. We parted company. They were selling a lot of records, and I just said, "I don't want to deal with you anymore. Let's forget it." They were just a huge drag to deal with at the time. We were so rich in talent that it was easier just to say, "Let's split." Nowadays I wouldn't, perhaps, feel the same way.

Emerson, Lake and Palmer were really presented as one of the first new-generation supergroups.

Yep. Definitely. They really delivered on stage, and were very exciting. It was theater, really. Personally, I don't think Carl Palmer is a particularly good drummer; he doesn't keep time, which is of the essence. But he looks great a lot of drums, a lot of flash. Keith Emerson had a lot of flash, and also good musicianship. Greg Lake had good songs and a great sort of stage persona. They were a great group to go and watch.

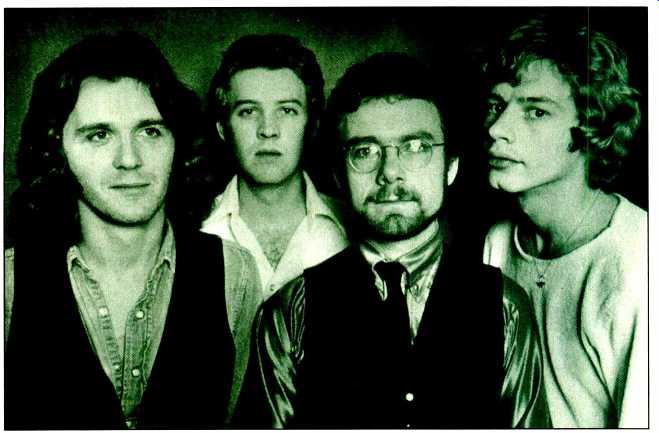

----------- Fairport Convention, which Island "inherited" from

a folk label.

How do you feel about today's heavy metal music?

I'm not a fan of heavy-metal music in terms of listening to it. I don't listen to it much, though I'm a fan of the attitude of it. I think the true spirit of a huge part of rock 'n' roll exists only in heavy metal today-real go-for-it, flat out, crazed and it's great that it's there. A lot of this art rock and fashion rock and all this stuff is sickening to me.

How involved were you as a producer with your rock bands in the '60s?

In the late '60s I was involved as a producer with Traffic. No, actually, in the late '60s Jimmy Miller was producing Traffic. He produced their really wonderful records: Mr. Fantasy and Traffic. The one I produced was Low Spark of High Heeled Boys. But producing Steve Winwood is walking into the studio and just being somebody that he can bounce off. That's it, be cause he's so. good. He's such a talent that he just has to play or sing or what ever. I would be involved in what songs would go on the album. I would work with them. I wouldn't say, "This goes, that doesn't go." I would come up with the running order of the album, and I'd work with them to mix it. If Winwood was performing, he'd per form. Then he'd come into the studio booth and we'd discuss it. I was a sounding board. When the other guys were doing their parts, Winwood would be in the booth with me. I'd be the one who actually put into words.... I'll tell you the best way to describe how it was, producing those groups: They needed somebody to actually say what needed to be said. The group would never really say it, because they were the group and I was the record company. See, if one group member was not happy with what another member did, he would never really say it or he'd spend four hours saying it, rather than just stating, "Listen, it's not very good. Do it again."

Right. This was the '60s, and I guess it wasn't cool if you weren't mellow enough to go with the flow.

Particularly our groups [laughter].

Did you run up some hefty studio time then?

The record that all studios should have up in their reception area, framed, is Sgt. Pepper. That's the record that took six months to make. After that, every body had to spend six months to make a record. Before that if you were going to make an album, you'd take maybe two or three weeks. Suddenly that was no longer possible. It had to take six months. It got to be so absurd that Emerson, Lake and Palmer, in the mid-'70s, spent $2 million making a record in Switzerland. I think the last Foreigner album also cost $2 million. It's just out of all proportion. As there are more and more tracks available to record, if you have people who don't really like to make a decision, and they're not pre pared to take the responsibility....

When a group gets big, a producer doesn't want to take responsibility, and none of the members of the band do, and the leader of the band probably wants to keep everything so he can decide later. Therefore you'll have 14 takes of a vocal, and eight takes of this, and more of that, until you have 48 tracks. You spend all this time not making decisions. When I started making records it was in mono, so you made the decision right there whether it was a good take or not. I still adopt that kind of approach of making a decision right on the spot, and getting it right on the spot. To me the mix shouldn't be something that takes a real long time. Everything should pretty much be in shape by then.

So you made sure things didn't get out of hand.

They never did get out of hand at that time. If I felt they were going to, I changed the structure of the deal so that the royalty rate was increased, but the artist was responsible for the re cording costs. For example, Cat Stevens' first album for us cost £4,000, the second one cost £7,000, and the third one cost £5,000. Now, those three al bums have sold over 20 million worldwide for us. But I foresaw explosions in costs. So in the renegotiations we made the royalty rate higher, and he absorbed the costs. In fact, those first three records were his biggest selling ones. The record after that cost £100,000, the one after that £300,000. It just went crazy and sales fell down. As the act gets stronger and more powerful, the less control you have anyhow. So if you want control, you should pay the penalty if you're wrong, and also be able to get the reward if you're right.

Whatever happened to Cat Stevens?

He is now a fully practicing Moslem in London. He teaches in school and spends his entire life in the Moslem community. He's not recording any more. Well, the last recording he did was a cassette which you could buy if you went into a mosque. It would tell you how to behave in a mosque and find your way around.

------ Cat Stevens, whose first three records for Island were his biggest,

selling more than 20 million worldwide.

That brings up another Island artist, Richard Thompson, who was a Sufi for many years. How did you come to sign his '60s group, Fairport Convention?

There was this American guy in London, Joe Boyd. He was and is a very, very tasteful person. He was involved in one of the key clubs of the late '60s where all the new acts would per form--the UFO Club in London. He started a kind of English folk label called Witch Season. On this label, which he had with Polydor, was Fair port Convention and, I think, The In credible String Band. I met him in a studio and we struck up a deal. Then he put all his productions through Island. One of the artists who I initially had, John Martyn, let his contract with Island lapse because the kind of music I was going into wasn't really this [English folk] kind of music, even though I really liked it. But I didn't really feel I knew it or knew how to make the re cords. John ended up on Witch Sea son, then with me again, and is still with me today. John first recorded with me in 1965 or '66. Nick Drake also came through Witch Season. Nick Drake was at Cambridge and he had come to see me and play me stuff. I said, "I love it, but I just don't know how to make these records." By chance he ended up on Witch Season. I got very involved in this label and this music. I got to really like it. Then Joe Boyd was offered a job in the Warner Bros. film department. He sold me his company and we inherited all these acts. I'm afraid we weren't really able to continue what he had done. I wasn't of that much value to any of those artists I inherited. Like, I don't think I was much help in guiding Sandy Denny or Fair port or any of them.

I don't see why it's important for the head of a record company to be at tuned to a particular type of music. Couldn't you just hire managers and producers who did know that kind of music?

I think you're right; I don't think it is important. But I think in that period everything would sort of emanate from my tastes. I was the only A&R guy, right? An A&R guy is the one who chooses who should be the producer for these bands. But if you don't really have the right feel for how they should go, you might pick the wrong producers. Now I don't think I necessarily picked the wrong producers, because I just stuck with the same ones they already had. But perhaps if I had a better feel for that music, I might have been able to put them with a producer who could have enhanced what they had and given them a chance to go to a wider audience. So I think I failed on those particular acts.

Is that kind of thing a problem for Island, or for any record company so closely associated with the direction and tastes of one man?

I think it's a problem if you try to sign too many acts, and be too many things to too many people. I think the key for an independent company is to be narrow, honestly, in what it's doing. I don't think you should be wide and have things all over the place. You can't possibly deal with it. If an independent company has one person's taste, if the taste is reasonably commercial you'll stay in business. If it's not, you'll go out of business-unless your costs are related to that taste, and to the narrowness of the audience you're going for.

To me the great labels are the labels that have an identity of style: Atlantic, in the early years and in the '60s and '70s with Led Zeppelin and Cream; obviously Motown in the '60s, with the album artists, the sort of icons they built, and Blue Note-you knew what kind of music you would get when you saw Blue Note. Those labels to me are great labels. It's the kind of label that I always wanted to have. We've wavered backwards and forwards at times, because one gets lured into one thing or another. But in general my philosophy is to try to have very few acts that you genuinely like, acts that are in the forefront of your thoughts all the time-not because you have a huge financial commitment to them, but because they're people that you know well and can represent in the way they like to be represented.

Couldn't your singularity of focus also be a danger for an artist? Say you get bored with an artist and decide you personally aren't interested anymore. So they no longer have your support, and that's it for them.

That's no more a danger than it is at any other company. The danger that exists in a major company is that the A&R person in charge is an employee, and as such can easily go and work for another company. So the person who sat down with you and said, "You must come and sign with me, I love your stuff, we'll do this and that," could be working for another company. Or he could get out of favor with his company because he hasn't been successful enough. Therefore, even though he may be championing his bands, he might have lost his credibility within the company, and therefore not be able to get anything done. There's no perfect way.

-- --- --

This concludes the first half of a two part interview.

(Source: Audio magazine, Feb 1987)

Also see:

Interview with George Martin (May 1978)

The Audio Interview: George Martin (June 1987)

The Audio Interview: Clive Davis: Finding Songs For Singers (July 1985)

= = = =