by David Lander

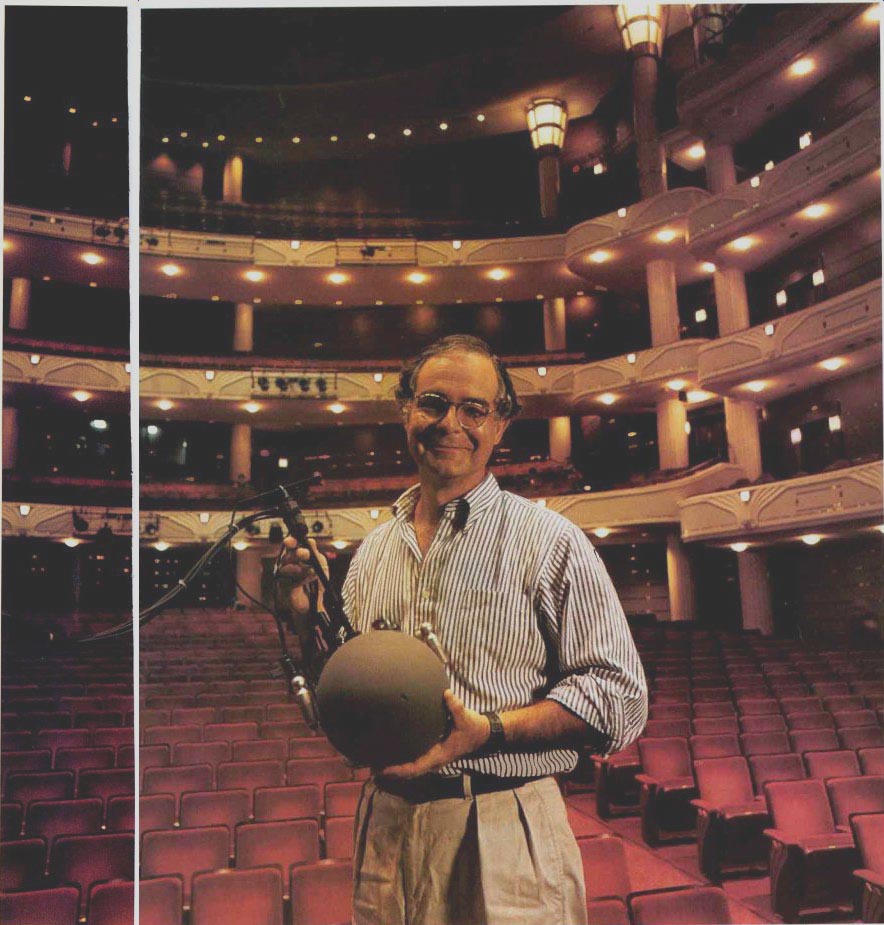

Peter McGrath has viewed-and heard-the high-fidelity industry from several perspectives. An audio enthusiast for as long as he can remember, he served an apprenticeship in hi-fi equipment retailing during graduate school and then went on to operate his own successful audio store. At the same time, he learned recording engineering, now a focal point of his career, and more recently took on the sales and marketing responsibilities for a loudspeaker company.

Born in 1948, McGrath grew up in Panama, where his paternal grandfather, an American engineer, had been killed while working on the Canal. His father became a successful entrepreneur there, and an uncle rose to the top office of that nation's Roman Catholic church. (McGrath jokingly traces his evangelical zeal to the Archbishop.) Young McGrath attended American schools in the Canal Zone before moving to the United States, where he attended the University of Notre Dame. Later, at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, he earned an M.S. in photography from the Institute of Design. 'While in the Windy City, he was intensely involved in the operations of The Audiophile, a veritable crucible of early high-end audio retailing. Then, in the early '70s, after moving to south Florida (where he still lives), he opened his own store, Sound Components. From its sales floor, he preached the high-end gospel to customers in what was then heathen territory.

Not long after arriving in Florida, McGrath began learning the recording engineer's art, and in 1979, he and Julian Kreeger, a Miami attorney with lofty connections in the classical music world, founded Audiofon Records.

Along with doing a great deal of local recording for the Florida Philharmonic, the New World Symphony, and others, McGrath has since served as recording engineer for 36 Audiofon projects as well as about 75 for other companies, including nearly 30 for Harmonia Mundi. He recently allied himself with Eggleston Works Loudspeakers, both as a shareholder and as the company's sales manager, where he finds a pleasing artistic symmetry in the fact that he met the speaker designer William Eggleston through the young man's father, also named William, a well-known photographer and longtime audio hobbyist.

-D.L.

Mark Levinson was instrumental in getting your recording career started. When was that?

Around 1975 or '76. Mark made it very clear that in order to become a master in the business of music reproduction, to really be an authority in high-end audio, I had to learn the recording side of the equation. He struck an analogy: How can you know if a photograph is a good print unless you know everything involved in the making of the negative and understand the whole chain?

I'd always had an interest in becoming involved with musicians and music, and recording seemed to be the best possible way that someone with my background could do that. So in the mid-'70s I started going up to New Haven and was privy to a lot of the recording activities Mark was involved in. I ultimately wound up buying a Stellavox tape recorder. Mark arranged for me to get some B & K microphones and his early microphone preamps and recording equipment. Then I pretty much went off on my own and started using these tools.

Can you relate your approach to recording sound to the stance you took when recording visual images?

In many ways, the approach-which is to use the best possible tools with the least amount of technical intervention-is very similar. The type of photography I was interested in was non-manipulative, which sometimes meant going to such extremes as printing the black borders of the 35-millimeter frame to show definitively that you'd not even cropped the photograph.

Those borders around photographs have become ubiquitous in magazine and advertising design in recent years. So today's art directors are borrowing something that noncommercial photographers used a long time ago.

They're applying a concept that started a lot earlier with people like Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, and my teacher, Gary Wino grand, who was a major influence on me. What Gary did was teach a fundamental respect for the power of the medium. Imagine him standing there making the following statement: "I would never presume to think that what goes on in here [and he'd point at his head] could ever be as interesting as what goes on out there [and he'd point away from his head]." For him, that was one reason why you don't manipulate an image.

So there you were in Chicago at the Institute of Design, where Bauhaus veterans Mies van der Rohe and the sculptor Mo holy-Nagy once taught and where the less-is-more aesthetic remained a cornerstone. School, however, was one of two realms of involvement for you then. Tell us about the other.

I was working in an audio store, The Audiophile, which was owned by two gentlemen who had doctorates in musicology, Jerry Roberts and David Shooks. What they taught me about audio was that it is meaningless if it doesn't convey you to the world of musical sound.

The Audiophile was a seminal high-end dealership. Where in Chicago was it?

At 8 East Erie Street. It later came to be known as Victor's Stereo, and now it's one of the Audio Consultants stores. To my knowledge we were the first Audio Research dealer the first to be taken on and the first to be terminated [laughs]. We were the first to sell the original Magneplanar Tympani loud speaker. As a company, we were involved with the distribution of many brands that have since fallen by the wayside but also many that became major staples. For example, we were the first people importing and distributing Linn Sondek turntables and Stax headphones. There were Quad electro static loudspeakers, Spendor and Rogers speakers, Decca phono cartridges from England, and Grace cartridges from Japan. It was very much the infancy of high end, a fun time.

After working for The Audiophile from 1969 through 1972, you moved to Miami to complete your master's thesis. Why did you choose Miami?

It was a place I had visited almost every summer as a child, the port of entry for Americans from Panama visiting this country. Coming from a place like Chicago, where the light was generally drab, I fell in love with the constant intensity of the south Florida light. It seemed the logical place. When I came down here, I realized that there was no store even remotelycom parable to what I had experienced in Chicago. Through a financial gift from my family, I was able to start one. I opened the business in late '73. I continued photographing, and the business grew.

How did you meet your Audiofon partner, Julian Kreeger?

A guy wandered into my store with some thing broken, and I didn't want to deal with him because I hadn't sold it [laughs]. He turned out to be an attorney, and the more I got to know him, the more I realized he knew everybody in the classical music world. I told him that I really wanted to explore the possibility of more involvement with recording. Julian said it didn't make a lot of sense to put forth all of this effort on local talent when he knew a number of very significant musicians who, for a variety of reasons, were being neglected by recording companies. He thought it would be wonderful to see if we could document what those musicians were doing, that it might have significant merit. This struck me as a wonderful idea, so we formed a company.

The first artist you worked with was Leonard Shure, an American-born pianist who died in February 1995. He had been a pupil of Artur Schnabel and became his teaching assistant before returning to America after the Nazis came to power. Shure, like Schnabel, did a lot of teaching, and he's said to have been difficult at times. What was he like to record?

Leonard remains in my mind a really extra ordinary man, a fabulous musician to work with. My understanding of Beethoven matured while working with him. He has indelibly printed on my mind what great mu sic-making can be.

Many people think that the jewels of the Audiofon catalog are its piano recordings. You've also worked with the pianists Earl Wild, Lazar Berman, Ivan Davis, David Bar-Illan, and Seymour Lipkin.

Seymour Lipkin is now head of the piano program at Juilliard and is having a major revival. He's currently performing the en tire Beethoven sonata cycle. We recently re leased his "Hammerklavier," and many people who have had the opportunity to hear it regard it as one of the better ones on record. And we're currently involved with two absolutely wonderful Russian pianists, 27-year-old Valentina Lisitsa and her husband, Alexei Kuznetsoff.

You've recorded Lisitsa in the Ural Mountains playing Shostakovich with the Ekaterinburg Philharmonic under the legendary Boston Opera conductor Sarah Caldwell. You've recorded her and Kuznetsoff as a duo and have released a pair of solo Lisitsa albums. Her CD covers show a face like Goldie Hawn's. Play the discs, and you hear hands like Glenn Gould's. As someone-Ira Gershwin, I believe--once said about Art Tatum, she should be arrested for speeding.

[Laughs.] In the many years that I've had the pleasure of working with pianists, I've never encountered a player quite like this. In four days of recording Valentina and her husband, there was never once a sheet of music in the hall. They were phenomenally well prepared.

I've never heard anyone who could pedal, who could get the nuance and color out of the left hand combined with pedal technique quite like she does. She's a relatively small person, yet she seems to be capable of devouring the Steinway. The power and dynamics she can get out of that instrument surpass anything else I've ever experienced, with the single possible exception of Lazar Berman, and you could fit three Valentina Lisitsas inside of him.

What's your ultimate goal in recording?

One of Gary Winogrand's strongest statements was that a really great photograph is one that renders you speechless. What I've strived to achieve in my recordings is the excitement of the event. I'm trying to re create the emotion and excitement conveyed when someone like Valentina is playing Liszt or of Leonard reaching the Olympian heights of the finale of Beethoven's Opus 110. It's not necessarily the performance I'm trying to re-create but that intellectual and emotional feeling you get when you're really involved in the music. I think it's a tired cliché to say that you're trying to capture the sound of the original event, because it's terribly naive to think there's that much correspondence. One of the most seductive aspects of a photograph is that it's trying to describe reality when, in point of fact, it has little to do with reality.

A photograph is in two dimensions; it may be black and white; it's separated from the context. What becomes obvious is that it has a reality unto itself. Through the photographic process, the artist has created a new reality, which has its own merit. In many ways, one can view the process of making a recording that way. The final product has a life of its own.

Julian Kreeger was the producer on all the recordings in the Audiofon catalog. How does he compare with the other producers you've worked with?

He's not dogmatic. On the contrary, he's very free-spirited. He loves to gamble on the possibility that anything can happen.

I've worked with producers who scrutinize and cover every note in a score. With Julian it's sort of free-form. Some of the most magical things you could ever imagine have evolved from this method. I mean, we're making recordings that are really performances...

...to the extent, in the case of your Valentina Lisitsa solo CDs, that the results are completely unedited. There are also performances on your Leonard Shure recordings that you made in just single takes. How often does that sort of thing happen in the recording world?

I think it's fairly rare unless, of course, the recordings are of live concerts. Even that can be questionable, because there's a lot of touch-up editing with post-concert takes to fill in gaps. Ours are truly recordings that are full performances. The philosophy behind that is to give, in the context of a recording, something that most closely approximates the real concert experience. And I think it engenders in the performer a certain kind of risk-taking that would not hap pen otherwise.

Let's talk about microphone technique. How do you determine placement?

The methodology is very simple. Julian, the artist, and I come back to my living room in the old days, we came back to the store and we listen to all the different experiments in terms of where I positioned the mikes. Then I make a selection that meets my requirements and keeps everyone else happy.

You use one method for recording orchestral music and chamber performances, but you prefer another setup for soloists.

The way I now approach a symphony orchestra evolved out of a specific micro phone that really has enabled me to rethink how you can deal with the size, scope, beauty, and dynamics-particularly in a good hall. The mike is the Schoeps KFM-6, which was introduced to me by Jerry Bruck in about 1991. He sent me the prototype after Schoeps sent it to him and he played with it. The KFM-6 is spherical, about the size of a bowling ball, with two omnis in it. I've not been able to get it to work to my ultimate satisfaction on a piano, but, boy, does it do a job on an orchestra. Incidentally, that was the mike I used to make the first recording of the Anonymous Four for Harmonia Mundi.

Jerry is the Schoeps distributor for the United States.

And also a very, very fine recording engineer. And one of the great teachers, a man of infinite patience. He has been and continues to be one of the great mentors, not only for me but, I would say, for most of the people who consider themselves purist recording engineers.

What mike setup do you use for piano recording?

I'm pretty much sticking to the same miking technique that I developed back in the '70s, a pair of spaced omnis. Back then it was the B & K 4133, later the Schoeps MKII-S. In some of our latest releases, we've gone back to that original B & K microphone, which is still startlingly beautiful.

But for orchestral music or concert events involving chamber music, I'm pretty much committed to the KFM-6 with, when necessary, additional mikes. On Harmonia Mundi's Mahler First with the Florida Philharmonic, I used six additional mikes for added detail and color.

Has all your recording been two-channel?

It has been up until very recently, but I've decided, for this entire season, to record the Florida Philharmonic in four-channel. I believe that the time has come. In order to start documenting this orchestra for future technology, I need to do that. Jerry has evolved a technique I have used, one which I believe is the most beautiful way to replicate an acoustical sound field, employing the KFM 6 with a pair of figure-of-eights in what we call a dual M-S [middle-side] matrix. We have one M-S pair looking at the right rear versus right front and another matrix pair looking at the left rear versus left front.

What associated equipment are you using?

A Nagra-D digital recorder with the Prism 24 bit A/D converter or sometimes other converters instead or in addition, whichever makes sense. I use, and have used exclusively, Transparent cable.

You spent more than two decades in audio retailing before leaving it about three years ago. What advice do you have for people interested in getting the best sound for their money?

Be as honest and as straightforward with the dealer as you can. If you have a specific objective, name it. Don't beat around the bush, don't play games. Typically, people are fearful that the dealer is out to take advantage of them. But the minute you start playing games, that invites the dealer to start playing games with you, and no one is served. At its best, buying a stereo system is really buying a passport. It's a doorway into another world. I'm on the boards of both the Florida Philharmonic and the New World Symphony. At one point, most of the Florida Philharmonic board members were former customers of mine. Not that I sold them equipment after they became board members. Rather, their involvement with hi-fi opened the door to music for them. That's the potential this medium has. Right now, hi-fi is the best way to learn about music. Going to concerts is not the experience a lot of people think it should be. I'm not suggesting you give up going to concerts, but many halls are not proper showcases. Either they're too large, have too much mechanical noise, or are filled with discourteous audiences who don't stay quiet. No one knows that more than I do, because on my tapes I've immortalized every hack and cough. I see people cringe when you have the most exquisite trailing cadenza in a Mozart concerto and this tubercular ward lets loose.

What are your plans for the future?

Three things. I'm hoping to further my involvement in the local recording scene. I'm hoping to build the name of Eggleston; I'm dedicated to seeing this speaker company grow. I'm also hoping to spend more time making commercial recordings. I'm open to recording acoustic music for anyone.

At Sound Components you became southern Florida's high-end pioneer. Do you think you might get back into retailing?

At this time I have no desire to get back to retail--although, in traveling around for Eggleston and seeing high-end stores and what I believe is lacking in them, I have been fantasizing about what I call a high-end boot camp, where I could train people.

I did it at Sound Components. David Shooks and Jerry Roberts engendered in me the fundamental aesthetic of what hi-fi's about: to create a musical experience. You glean tremendous wealth from these little machines that glow or these transistors that run hot. These boxes may look ugly in your room, but they create this emotional experience. It really is magic.

How much does a person have to spend for magic? Sound Components specialized in very expensive equipment.

During my last years there, we sold just about everything. And there were some aw fully good components avail able in the so-called mid-fi realm that really did make beautiful sounds. A pair of small planar speakers with a high-current receiver is still a sublime musical experience.

Adapted from Audio magazine Feb. 1997.

Also see:

The Audio Interview: Mastering the Art of Vinyl--Mobile Fidelity's Herb Belkin (Jan. 1996)

The Audio Interview: Sheffield Lab's DOUG SAX and LINCOLN MAYORGA (Jan. 1984)