----------

THE AUDIO INTERVIEW -- Bob Carver--the boy wonder...all grown up.

by Ivan Berger

Arguably the most creative audio design engineer of his generation, Bob Carver is known throughout the industry for his playful attitude and the fanciful names he's given his inventions.

Over the years, he's built three companies, lost two (which faded rapidly after his departure), and regained one, carver corporation, just weeks after this interview. Carver Corporation's remnants have now been moved in with his latest company, Sunfire, in Snohomish, Washington.

Two common threads run through most of Bob's innovations: the urge to do more with less (as in the small but mighty Sunfire true subwoofers and the Carver magnetic field amp) and his compulsion to do it in the most interesting ways possible. Two uncommon companies now occupy him, Carver and Sunfire he intends to maintain them as separate brands with separate market positions. "We're designing some neat stuff for Carver," he adds.

Bob’s wife, Diana, who helped him fund Carver Corporation, chimed in from time to time during this interview.

-I.B.

Which came first, you- interest :r electronics or yaur it serest in rtiu'sic?

They were simultaneous. My mother was a pianist, out my father was an engineer. One day, when I was very small my dad came home and said, "Lab, we're going to see ou_0 io_ces today."

And so you saw an oscilloscope.

That must have been it, because I remember being absolutely astonished that we could see a voice. On the wa7 over. I said, "H ,w can we see oar yokes? That's not possible, Dad." And I re -

member yei ing into the microphone to make the wigg&s po bigger. I think that was the beginning of it all.

When did you actually start doing electronics? When I was a Cub Scout, I built a crystal radio.

But my fist real interest in electronics was for model airplanes, radio control, so I butt a sys tem from C. magazine. Then, whet stereo records came out, I saw an article in a ntzine, "How To Build a Stereo Amplifier," and 1 bilk nne. It didn’t work right; I must have built it wrong. The instructions weren't very good. So I tried to build my own without a set of instructions, and ultimately I got it to work.

From then on, I loved building amplifiers.

How powerful was it?

It probably wasn't even 3 watts, but I thought it was a hundred. I mean, it sounded great. I had a single-ended 6AQ5 output stage.

Today, a single-ended 6AQ5 stage goes for about $15,000. Back then, it could be built for less than $2.

But my first products were all solid-state. When I finally built a commercial tube amp, at Carver-the Silver Seven--I did it as a work of love.

Tube amps are fun to watch. Didn't you once put a tube behind a little window for that reason? That's my Sunfire tube preamp. It has three tubes behind a little window. But the three tubes didn't look good enough, so I put a mirror behind them so it looks like six. Then I put mirrors on the sides. From a certain angle, it looks like an infinite number of tubes.

And I'll bet it looks great in the dark.

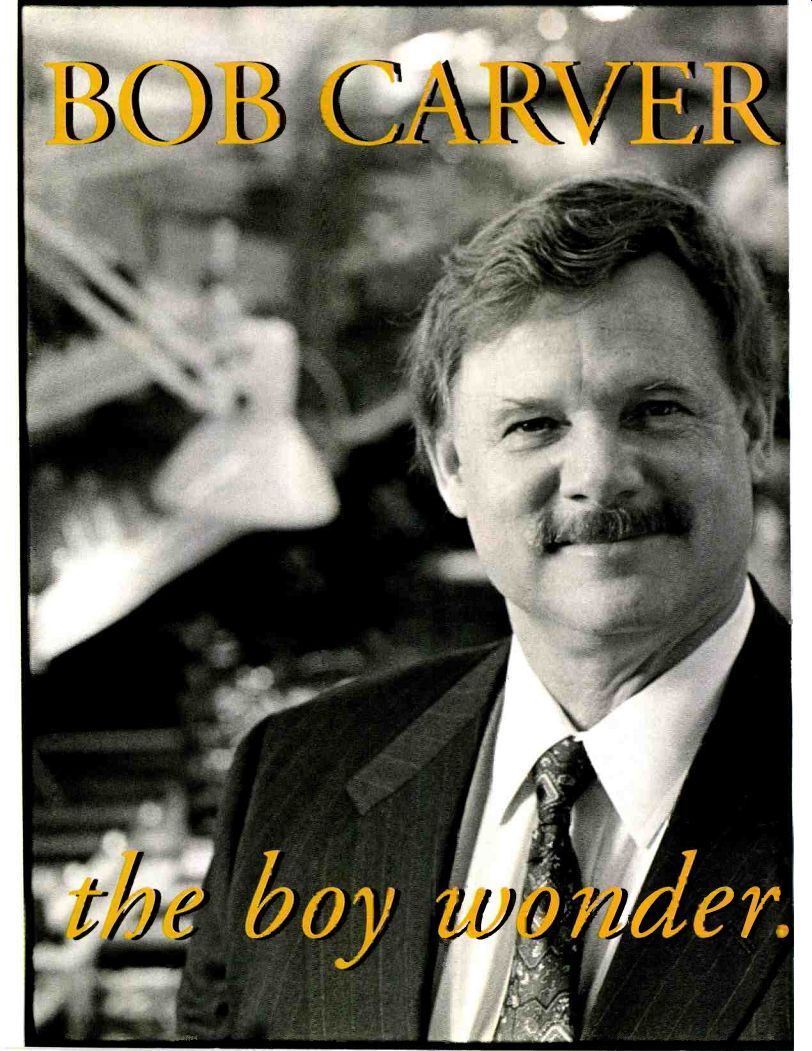

--------THE PHASE LINEAR 700 AMP WAS BOB CARVER'S FIRST COMMERCIAL PRODUCT.

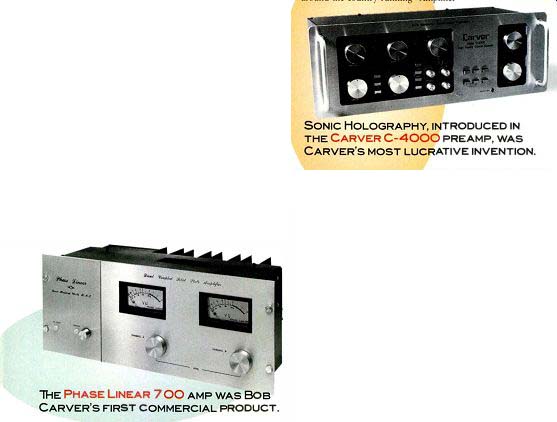

---------- SONIC HOLOGRAPHY, INTRODUCED IN THE CARVER C-4000 PREAMP, WAS CARVER'S

MOST LUCRATIVE INVENTION.

Well, it didn't quite, because the tube filaments didn't light up enough. I put little incandescent light bulbs behind each tube and ran them at a low voltage so they'd have a warm glow. Now, in the dark, it looks like there are a lot of tubes, a beautiful glow.

You once built an amplifier in a coffee can? That circuit was the basis of my very first commercial amplifier, the Phase Linear 700. But when I was designing it, I didn't have any money so I used a coffee can as a chassis. Since I couldn't afford a power transformer, I built it line -connected, which made it immensely powerful and very light in weight. It put out so much power it was silly, and I managed to get it to the point where it didn't blowup.

Back then, McIntosh had a guy named Davie O'Brien who went around the country running "Amplifier Clinics" at hi-fi stores. They'd advertise it in the papers, and every body would take in their amplifiers. It was exciting to go to a Mac Clinic and watch the amplifiers be tested. Dealer events were big things. Once, I got all dressed up in my suit and took my date.

D.C.: The quintessential nerd "I -love -you." Wonderful! B.C.: Anyway, I took my amplifier to the Mac Clinic. I knew exactly what it would do, but I needed the credibility that the McIntosh Clinic would give me. Amplifier after amplifier would go through there, and Davie O'Brien and the rep would make a graph and give it back to the owner. The graph always looked terrible; it had tons of distortion at the low end and tons at the high end. But McIntosh amplifiers always were ruler -flat, and their distortion stayed pretty much at the bottom of the graph. The Clinic was a very impressive thing for McIntosh to do. It showed that you got what you paid for.

If you could afford McIntosh, you would get low distortion over the whole band at full rated power; you couldn't do that with anybody else's amp.

What people took to the McIntosh Clinic in those days was mostly tube amplifiers. Someone would plunk his amp down to be tested and say, "30 watts." Or he'd pick up one, struggle, strain, and grunt, "60 watts per channel." Those were big amps. I took my coffee can amp and went, boop-de-do. Remember, it had no trans former, no output transformer just transistors mounted around the coffee can. With one hand, I put it down and said, "700 watts." It was a Frankenbox, with wires everywhere.

They ran it up, and Davie asked, "How much?" And I repeated, "700 watts." It went 200 watts, 300 watts, 350, 400, and everybody is really quiet in the room now, looking at the 'scope and listening to Davie calling out the numbers: 200, 250, 300, 350, 400....' Where does it clip?" he asked me. Before I could answer, the whole building went dark; my amp blew the fuses.

By and by, they got the lights back on and finished the test, though we dropped the power back to 350 watts to keep the room lit. I said to myself, "I don't know if it's going to make 350 at 20 kHz; it might not here." So I blurted out, "I want it tested at 300 watts per channel." And they gave me this beautiful curve, just flat response down at the bottom. And Davie O'Brien, his face was sort of going white.

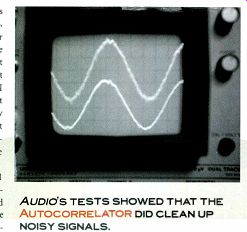

------AUDIO'S TESTS SHOWED THAT THE AUTOCORRELATOR DID CLEAN UP NOISY

SIGNALS.

As soon as I got my graph, I knew I had something very valuable. I intended to reprint it and use it in a brochure, with the McIntosh Clinic's credibility be hind me. Nobody believed that my amp would really do it. I reprinted that graph, spending every dime I had making copies of it. Then I went to a banker and told him I needed money to start up a company. He said, "Okay. I'm a high -roller; I'll lend you $5,000. You're going to buy parts with this stuff, right?" I said, "Yes." But I lied. As soon as I got the money, I went out and bought advertising. We took out a very small ad in Audio. It announced that I had these new -generation amplifiers, 700 watts rms, and told readers they should write us for more in formation. A lot of letters came in.

Was yours the most powerful amp on the market then? There wasn't anything even close. The biggest solid-state amp was the Crown DC -300, at 150 a side, and mine clipped at 450, if you re call. I was chicken to rate it at 450, so I rated it at 350. McIntosh had a 350 -watt mono tube amplifier, the MCT-3500, but it was a monster. It was half the size of a refrigerator and had who -knows -how -many output tubes in it, a big bank of them.

It was partially because of the McIntosh's 350 watts that I chose 350 watts and partially because I had done some research to find out how much power was needed to play music the way I wanted to listen to it. I had four University 315C coaxial three-way loudspeakers in a huge box. They were moderately efficient-like 86 or 87 dB, which is not all that efficient by today's standards. I remember watching an oscilloscope while I played music and deciding that I needed 52 volts of output swing to not clip the amp. That was pretty loud, but it wasn't crazy loud. It turns out that 52 volts into 8 ohms is about 350 watts rms, so there was a serendipitous convergence there.

How many amps did you sell from your ad? It got me started. When I sent out the brochures, I included a copy of the Mac Clinic graph with each brochure-that gave it the credibility I needed. I still didn't have any money, so when dealers wrote in, I said, "You have to buy two of them to be a dealer, and you have to pay for one in advance." The money for one would buy enough parts to build about two, two -and -a -half amplifiers. I'd send the dealer one amp, back -order the other, and send the second amp to somebody else who had sent me money. So I bootstrapped it; as soon as I got some more money, I'd finish the dealer's order.

And then that Audio ad got reps' attention--which is when I learned about reps, or factory representatives.

Some local dealers came over and told me about how the industry worked.

I picked the name Phase Linear for my company because it sounded familiar to everybody even though it didn't exist. Everybody said, "Oh, yeah, I've heard that name," when, in fact, they hadn't.

Where did Phase Linear go from that first amp? A smaller amp, 200 watts per channel instead of 350, and then a preamp, a speaker, and a tuner to round out the line.

Did any of those products have any thing special about them?

Yes. When I was little, one of the things I loved was show and tell at school, because when I took something, everybody would sit around and watch. I couldn't act, I couldn't play a piano, but eventually I could design amplifiers. So I said to myself, if I come out with something, it has to be really very special. I would rather die than come out with a me -too product. I wanted my products to have some real meaning.

------- CARVER'S AMAZING Loudspeaker HAD A RIBBON DRIVER THAT W DOWN TO 100 HZ.

When I designed the Phase Linear preamplifier, I felt the biggest unsolved problems were noise and dynamic range. So I developed a noise-reduction system, the Autocorrelator. It was a single -ended noise reducer that cut noise about 10 dB. And I developed a dynamic range enhancer, which I called the Peak Unlimiter and Downward Expander. The Autocorrelator was unique. The Peak Unlimiter and Downward Expander wasn't unique, but it didn't pump or swish the way all other dynamic range enhancement circuits do.

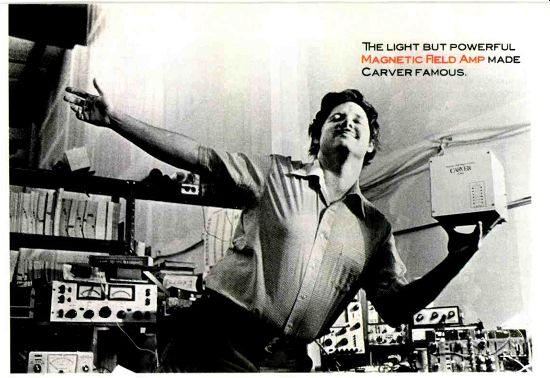

-------- LIGHT BUT POWERFUL MAGNETIC HELD AMP MADE CARVER FAMOUS.

How did you accomplish that? Most dynamic range enhancers would try for 10 or 20 dB of compression or expansion; no matter how artfully that's done, you'll hear it working. But if it's a small change of just a few dB, done art fully, you won't. The artful part was building mine to affect only the top and bottom of the dynamic range. If the Peak Unlimiter added, say, 2 dB of boost at the top of the dynamic range, the Downward Expander cut the bottom by 4 dB, and I had a great, big, do nothing middle band between, I'd get 6 dB more dynamic range without pumping.

How did the Autocorrelator work? It reduced noise and hiss, record hiss. It was a four -band voltage -controlled gating system that looked at the signal coming along in each band to see whether it was highly correlated, like the ringing of a tuning fork, or more noise-like-the sibilants in speech, for instance.

The gate's threshold would vary with the signal correlation in each band.

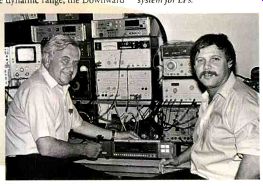

------------LEN FELDMAN, WHO OF BOB CARVER'S PRODUCTS FOR THIS MAGAZINE, WITH THE INVENTOR IN THE EARLY '80S.

REVIEWED MANY

When you're creating something, do you say, "I see a problem, let me come up with a solution," do you just tinker until something hits you, or do you say, "Hey, that's a great idea. How can I use it?"

It's "there's a problem here," and I say, "I know there is a way around it. I know how this can be solved." For example, the in tractable problem of surface noise on vinyl records. Double -ended solutions-encode/decode-were well known. They were really no big deal.

Like Dolby noise reduction, dbx noise reduction, and the CBS CX system for LPs.

Right, but doing it single-endedly, where you take a signal that hasn't been specially en coded and somehow figure out which components are noise and which are signal, and then toss out the noise without tossing the signal out-that was a trick.

Why did you finally leave Phase Linear? As time went on, I sold some of the stock in the company to some investment bankers, and they wanted a return on their money. Fair enough. One day they came to me with visions of sugarplums dancing in their heads and told me that it was time to make a public stoc quite ready. I'm not ready to se what "going public" meant-s k offering. I replied, "We're not 11 out yet." (In my mind, that's somehow selling out and losing your soul. It's not true, of course, but that's what I believed back then.) The bankers kept persisting, but I refused.

One day, I bopped into the board meeting, and I knew some thing very special was up: There were all these guys with suits who I had never seen before, and there was a tape recorder in the middle of the table. Before I knew. it, somebody said, "We make this motion. All in favor, say aye....We make another motion. All in favor, say aye." I was going, "What? What? What?" And after about three or four motions, I was out. They bought me out, and that gave me enough money to start Carver.

How long after that did you start Carver? About a year.

You made up names for two of your companies, Phase Linear and Sunfire, so why did it take a contest to come up with the name Carver Corporation? I had read a book by the advertising genius David Ogilvy, who said, "Never name your company after yourself." (He has since rescind ed t I thought that I needed a good name and ran a contest.

A lot of readers from Stereo Review and Audio wrote in, and 75% of them said that I should name it Carver.

If 75% suggested the same thing how did you pick a winner? D.C.: We had a lottery. A guy named Tony something (Redfern?) in Arizona won an amplifier and free a trip to the factory, not someplace like Paris; we didn't have enough money.

The products that people think of you for are the Carver products, and not just because your name was on them. At Phase Linear, you made your name with a humongous amp, but then other people made humongous amps. And the Downward Expander and the Autocorrelator didn't make that big a splash. Then, at Carver Corporation, you came up with a whole bunch of ideas, like Sonic Holography and the Magnetic Field Amplifier. Was that amp's name legitimately descriptive or just a name you hung on it? Mostly it was a name I hung on it. My names always hark back to something scientific that you can grab onto, but mostly they're names that I just pull out of the air.

How did the Mag Amp work? Any audio designer worth his salt is searching for a Holy Grail. That Holy Grail in amplifier design is an amp that is very efficient, so it doesn't get hot and can be very small yet have immense power out put. To do that requires a tracking power supply, which can give the designer that all-but-impossible achievement of high-almost infinite-output, zero heat, utter reliability, and minuscule size. Be cause if the power supply tracks the audio, there can be little or no voltage drop across the output transistors; it's that voltage drop and simultaneous current that make the transistors get hot, because power is volts times amperes. If the voltage is low and current is high, there is still no heat and the efficiency is high. All amplifier designers at one time or another have tried to make a tracking power supply; I was no exception.

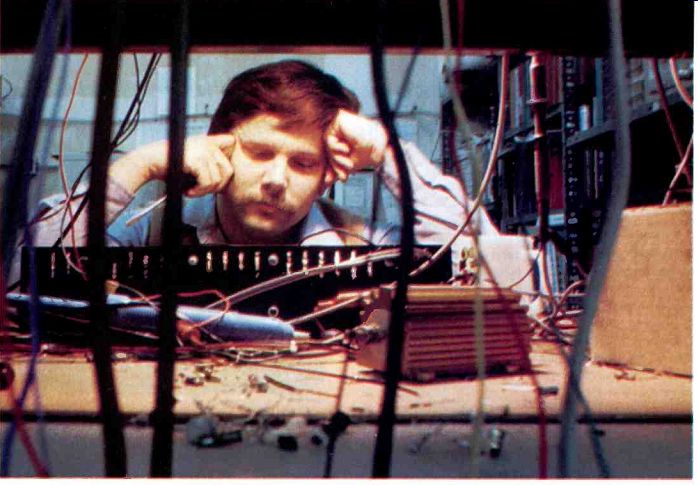

Tom Holman and I sat in a coffee shop years ago talking about tracking power supplies. We both went home to try and make one, and we both failed miserably. At one CES, Tom showed an amplifier with a tracking power supply. It was very low -powered but al ways blew up. I was at home trying to make mine. I spent almost a year working on it, and I was often almost in tears. It was always, pool. I'd get it to work for 10 minutes and then zzzip, poof, it would blow up for no apparent reason. After a year of this, both Tom and I threw in the towel. And I built the Mag Amp.

-----------THE PHASE LINEAR 4000 PREAMP UNLEASHED THE AUTOCORRELATOR, PEAK UNLIMITER, AND DOWNWARD EXPANDER.

The Mag Amp has a tracking power supply of sorts, but its tracking is a stepwise approximation, a 12 -step approximation to a sine wave. There were three positive and three negative power supplies, and the sine wave would step through the different power -supply rail voltages -12 steps, if it cycled up and down through all of them. The amplifier would switch rails as the signal amplitude went up and down.

It was crude and wasn't that efficient. The Mag Amp got hot and couldn't drive super -low -impedance loads. It had its flaws, but it was okay. And it was efficient enough to shrink the size and didn't have to have heat sinks. It couldn't drive 1.5 ohms, but it could drive 3 ohms or so successfully. That was what really put Carver Corporation on the map.

I think the Mag Amp was one of the things that got the high end to look kind of askance at you. The name was funny, and it was not a high -current design, which, if memory serves, was already a buzz word back then.

The figure of merit for an amplifier changes over time. For a while, it was high slew rate. Before that, it was high damping factor. Then it became high current. It's as if the concept of limits doesn't exist.

How much current do you need? If you need 10 amperes, is 100 amperes better? Of course not.

As I understand it, the art of engineering is largely a matter of set ting proper limits-saying, "Okay, I want more, but there's a certain point beyond which I don't." That is the art of engineering. When I look around me at the audio landscape, I see immensely talented men and women spending an immense amount of intellectual time, effort, and energy searching for something that is a sort of silliness. If they spent the same amount of energy designing something that was real, we would advance audio much faster.

I remember back when distortion of 1% and 5% was fairly common, and 0.1% was a big deal. But then we got lower and lower distortion specs, largely the result of more and more feedback. The high end turned around and said, "Wait a minute. We're using all this feed back to get this meaningless improvement, and feedback is not a good thing."

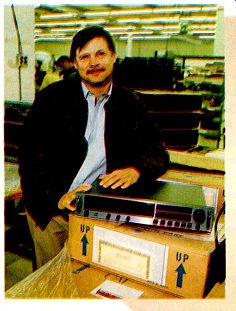

---------- AT THE CARVER PLANT, BOB SHOWS OFF ONE OF HIS TUNERS

I was so proud of the high -end guys who said that; that was great. Exactly. The concept of limits applies. What's the lower limit that's audible? To find out, you have to do some research. You have to at least listen.

Getting back to the beginnings at Carver Corporation, your first two products were the Sonic Holography preamp and the Magnetic Field Amplifier. What did Sonic Holography do? With a two -channel system, when you play a stereo program you hear a flat curtain of sound strung between two speakers. It's neither particularly convincing nor real-sounding. So I wanted to present sound waves to our ear/brain system in a way that would fool us into believing we were in the presence of a real live sound source, like an orchestra. I was trying to add depth and width and a palpable three-dimensionality.

The reason stereo turns out to be, at best, a flat curtain of sound between two speakers is that, in real life, we hear two arrivals for each single sonic event, one at each ear. When we listen to stereo, however, we hear four arrivals for each sonic event, one per speaker per ear. That's confusing. The time relationship between the two signals in real life, between the single sound's arrivals at each ear, is one of the things that tells us how far away its source is; it also tells us whether it's coming from the right or the left and gives us the sense of three -dimensionality. That's why we have two ears. If your ears are about 8 inches apart, the interaural delay is approximately three-quarters of a millisecond-or about 700 microseconds.

The Sonic Holography circuit made a cancellation signal, so that the sound the right ear heard from the left speaker was canceled by an inverted sound, 700 microseconds later, from the right speaker.

So there were two arrivals per sonic event, which is what we're used to. And when you cancel the two extra arrivals, the soundstage rather than being a flat curtain of sound-becomes something that has width and depth and even height.

I hear depth, even without Sonic Holography. Where's it coming from? Depth arises because, by sheer chance in the recording process, there are out -of -phase signal components that cancel many of the signal components flowing into our ears from the speakers, reducing much of the signal to two arrivals instead of four. To the extent that those components cancel by chance, we get a palpable, believable image and sound-stage. We hear depth when we hear two dominant arrivals during the interaural de lay; the more and louder the other arrivals, the less depth we hear.

The speakers are important, too, because a speaker can launch more than one sound wave for every electrical sound impulse put into it. For example, a speaker may have hard, diffracting edges. Or it may have multiple drivers that are not arrayed vertically, and their arrivals overlap; they make their own different arrival times. Speakers like that pretty much make a flat curtain of sound. If a speaker has good imaging qualities, it's because attention has been paid to the wave launch and the wave -launch geometry of the sound source.

The best depth I've had in my house has been with electrostatic speakers.

Panel speakers do give a great sense of depth. They're pretty coherent, so they really don't make a lot of wave launches. And they send a sound wave backward, which bounces off the wall behind the speakers and then returns. Sound travels 1 foot per millisecond, so if the speakers are 3 feet away from the wall, that's a 6-millisecond delay. That delay, in and of itself, makes a significant contribution to ambience. Simply because the signal is delayed, it helps create the illusion of a big soundstage.

With the Carver C-4000 preamp, I got tired of using Sonic Holography after a while. It was this great new toy when I first got it, so why do you think I used it less and less? I don't know. It might be that your tastes changed. It might be that the speakers you were using really did make too many launches. Re member, Sonic Holography cancels two unwanted signals by generating two others that cancel. But suppose they don't cancel? Then you've made more. You start with four signals, your two canceling signals don't cancel, and suddenly you have six or eight. That would probably make your ear/brain work very, very hard to make sense of the sound field.

For Sonic Holography to work right, you had to be exactly on the acoustic center line between the speakers. If you were half an inch off, you'd begin to dilute the effect, because the cancellation signals would no longer cancel. They would mostly cancel, but they would add as well, making more arrivals. If you didn't have the speakers just so, and the room just so, and your position just so, Sonic Holography would probably make the situation worse. These factors were far more critical in the early Sonic Holography than the later version. I worked on it a lot to make it so that if you moved around in your seat, the images would stay locked. That took some doing. With the early version, you really had to stay right dead on the center line for it to work.

Of all my inventions, Sonic Holography was the one that brought in the most money. I'd thought it would be the Magnetic Field Amplifier, the little cube, because I sold more units. But I was wrong.

What was "amazing" about the Amazing Loudspeaker you did at Carver? First of all, it was the world's first wide -area, full -range ribbon. At that time, the lowest any ribbon loudspeakers went was 800 Hz.

This one went down to 100. It went from 100 Hz all the way up to 20 kHz, with no crossover. So it was smooth and seamless. And in the voice region, that's a nice thing to have.

How did you accomplish that? By making it wide -area. I had two thin metallic ribbons going down between the magnets, but they were glued to a big, wide sheet of Kapton. The glue was Pliobond, a model airplane cement, which is compliant. At low frequencies, the ribbon would move the whole piece of Kapton back and forth. That piece had greater area than a 12-inch driver; it was about 5 inches wide and 5 feet long.

Did it have the excursion of a 12 -inch driver? No. It had, I would say, almost an eighth -inch excursion. But be cause it had a lot of area, it could play loudly.

And a speaker doesn't need to move so much air if it goes down only to 100 Hz.

Right. At high frequencies, the Pliobond would decouple the rib bon from the Kapton, so the Kapton wouldn't move. Having only the ribbon element move reduced the mass, so it would act like a very -high -frequency driver.

It couldn't decouple very much.

Think of a tweeter. Along the diaphragm's edge is what seems to be a very inflexible coupling. If you push the diaphragm, it doesn't move very much. But a tweeter doesn't have to move much.

Anyway, it worked: I was able to get a lot of SPL out at 100 Hz from a ribbon. That was the first thing that was new and unusual about it.

The second was that I was able, for the first time, to get a lot of high-SPL, low -frequency bass out of a panel speaker. The drivers in the Amazing Loudspeaker, a mix of ribbons and 12 -inch cones, were mounted in dipole fashion, so that they radiated out the front and the back of the panel. Now, a panel speaker, with no box containing its back wave, will at some point start rolling off the bass; at low frequencies, when the wavelengths get big enough, the waves from the back will come around and cancel the waves from the front. As you go down in frequency from the point where this be gins, the bass rolls off at 6 dB per octave. The bigger the panel, the lower the rolloff begins. With a panel whose dimensions are, say, 2 x 5 feet (a common size for panel speakers), the bass will normally start to roll off at 100 Hz.

------------

THERE'S MORE TO THE SUNFIRE CLASSIC VACUUM TUBE PREAMP'S PRETTY GLOW THAN MEETS THE EYE.

So panel speakers were known for not having much bass. To improve it, I made the Amazing's woofer magnets very, very tiny and the cones very, very light (just the opposite of my Sunfire sub-woofers today). Because the magnets were very tiny, the speaker was underdamped, creating a peak in the response--a giant peak, at about 28 or 30 Hz. The cones operated only below 100 Hz, so their response would rise at about 6 dB per octave below 100 Hz until it reached that peak and then go down. But the panel is an acoustic short circuit, so it rolls off response at 6 dB per octave below 100 Hz. The sum of this underdamped woofer response and the panel's rolloff was flat system response down to about 30 Hz. That had never been done before.

Carver was publicly financed? After the Phase Linear experience, I decided not to have any partners, so we financed it ourselves. Then, in 1985, we did decide to go public. That seemed to be a good idea except, again, the control left me and it was a repeat. It's my karma; I do it to myself.

Why were you kicked out of Carver? It couldn't have been for refusing to go public.

I did a very dumb thing. I chose directors who had nothing to do with the audio business. Audio companies are sort of weird, be cause we're all weird, us guys in audio. We sit around until the wee hours of the morning listening to music. We engineer at night. One of the board members said, "Bob, the fact that you can't get your job done in eight hours means you're not good. You can't do your job properly."

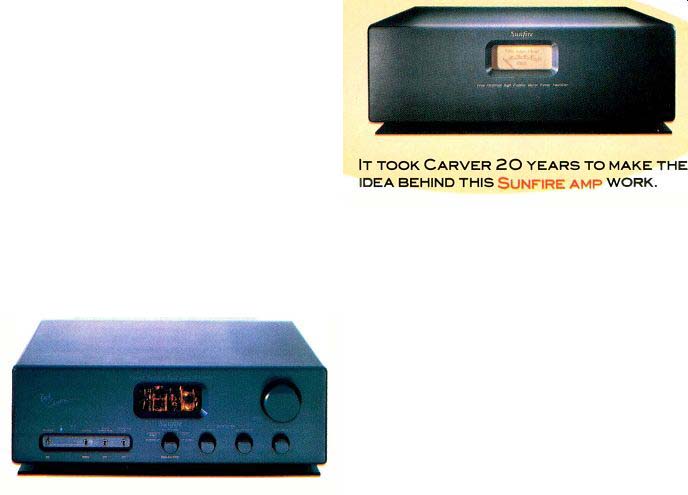

------ IT TOOK CARVER 20 YEARS TO MAKE THE IDEA BEHIND THIS, UNFIRE AMP WORK.

But it's in the evening when nobody is around to hand you all this business-related stuff that you can do research.

I didn't want to do the business part; I wanted to do research. I wanted to sit at my lab bench and invent. So, not wanting to take full responsibility for the company, I handed it over to people who weren't in audio. And when they tried to do what seemed to me crazy things, I would object. So they voted me out.

What the board of directors didn't understand was how much our industry is based on positioning-all industries are. When you think of Black & Decker, you think power tools, and you'd no more buy Black & Decker milk than a Borden power drill. But the directors wanted to grow the company indefinitely. They wanted it to enter different fields and be everything to everybody-simultaneously to be what Carver is, to be super-high-end, and to sell $29 and $39 radios to every garage and Costco. Our industry won't put up with that. When our dealers objected because that didn't go with our position, the board of directors had the CEO tell them, "If you don't buy all the Carver stuff, we're not going to let you sell any of it. We're going to cut you off." And the dealers went bananas! So Carver lost its position and lost its way.

Did you start Sunfire as soon as you left Carver? When I was kicked out of Carver, Diana and I decided to travel and to smell the flowers along the way, to be the most loving couple we could be. We decided to share life every day, all day long, together.

And to hell with business.

How long did that last? B.C.: Not long. It was wonderful. But we decided, you know, we had to be in there. And then one day, Diana evicted me from the living room.

D.C.: He was working on some kind of system that had woofers and a big -screen television, and he had six or seven pair of Amazing Loudspeakers in various stages of tweaking in the dining room, the other parlor, and the hall.

B.C.: I had them all in the living room! The rest of the house was beautiful! I didn't let it leak out of the living room! D.C.: And then he would work all night. And I never heard a finished piece of music. He would never listen to music; he would listen to parts of music. It was "musicus interruptus," passage after passage. He would listen to a few pieces that had certain kinds of energy content over and over again, trying it this way and that way to get it right. And then he would do sweeps-whooeeep, whooooeeeep. And he played one movie so loud...

B.C.: Total Recall.

D.C.:... and there was so much vibration, the ceiling came down because the plumbing broke. Water landed in the piano. And the ceiling was plaster, real plaster! My solution was a place where he could work on his projects, just outside the d I even had an architect in mind. And then Bob started Sunfit What's the difference between the Sunfire and Carver Lightstar amps? They're exactly the same. I had just finished designing the Lightstar when I left Carver. And I took that design over to Sunfire.

The reason I could do that goes back to the time, 20 years earlier, when Tom Holman and I first tried to make tracking power sup plies and both of us gave up. I came back to it during the Lightstar days, and I got it to work this time-I got it to work in spades! It had everything that a tracking power supply should have. It had immense efficiency. It didn't get hot. It didn't need heat sinks. It could drive 1 ohm. It was an ideal amplifier. And it was really my old patent that I went back to and got to work the second time around.

How did you make it work? Oh, it was so simple! It was just a dumb oversight 20 years ago. It was not because of devices or technology; it was because we didn't think of controlling transition speed. We made the amp switch very fast to maximize efficiency, but when it switched very fast, it created an electromagnetic pulse that radiated from the wires right to the switching transistors and the control circuitry. And the control circuitry would go bananas. Two transistors would turn on simultaneously, creating a short from B+ to ground, and both would blow up. This wouldn't happen all the time; the amp would be running for a while and then, for no reason we could detect, it would blow up.

Why did this happen only some of the time? To this day, I don't know. It was one of those things that was just on the hairy edge, but it would make the control circuitry hiccup.

Whenever the control circuitry would hiccup, both transistors would turn on. And since it's a straight path from B+ to ground and both transistors are on, poof city. When I finally, by intuition, realized that, I slowed the transition down.

The pulse of a signal is equal to ; that is, it's proportional to the rate of change of the current flowing through the wires. A straight -up pulse's _L is almost infinite; I bend the pulse ever so slightly, and 4- drops by orders of magnitude. Once I turned the pulse into a slope, the control circuitry was happy and the amp stopped blowing up. It was so simple, yet it took me 20 years to figure it out! And it's still 12 -step? No. That's the beauty of the Tracking Downconverter. It's infinite steps, smoothly varying.

What's in the future? By the time this interview hits print, I'll have shown my Cinema Ribbon speakers at CES. They're an extrapolation of the high-pres sure, high back-EMF driver system I use in my Sunfire True Sub-woofers. High-pressure, because it's all in a little box and the drivers are still moving violently, so the pressures are high. And the combination of high back-EMF and high pressure yields high performance from a relatively small box. I've just moved that idea up into the midrange and high frequencies.

It's a ribbon driver, in a little box that's only about 6 inches tall, 3 inches wide, and 4 inches deep. But it can play as loud as a much bigger speaker with two 8 -inch drivers and a tweeter. It can play 105 dB SPL from 100 Hz up--actually, from 85 Hz up. So it can play really loud.

It's also the first fly-by-wire speaker on the market. I call it "fly-by-wire," because it's all electronically controlled, like a modern jet.

Every speaker has to have some kind of excursion limiter-usually, the spider-to keep it from bottoming out with a loud clang. But mechanical excursion limiters throw away a lot of performance; they're crude, limiting maximum SPL and keeping the speaker from achieving minimum distortion. That's a terrible compromise to make. A better way is to throw away the spider and have the limiting done by a sensitive electronic circuit.

With a normal speaker, especially a little one, if you turn the volume up too much, it starts to sound harsh because it's being over loaded. So you back off until it sounds clean, throwing away 10 dB of useful SPL just so the peaks don't overload the speaker. But if you have the drivers under electronic control, rather than mechanical control by spiders and all sorts of nonlinear stuff, you can conform the electronic protection circuitry to the speaker's mechanical dynamics like a beautifully fitted glove. And you can get 10 dB more out of it.

In the Cinema Ribbon, electronics control the damping, the excursion, the dynamics, the details of the frequency response, and the spectral response.

What's that little amp on the desk? It's about the size of a pack of cigarettes! I can't really talk about it much yet. It's a 300 -watt subwoofer amp for cars. It goes up only to 200 Hz; then it's got to cross over.

That sounds like Class D.

Class D wouldn't be this small. I'll be showing it at CES along with a car subwoofer, a high-pressure sub. The combination will be small and high-powered, and it will have lots of bass. But unlike the Sunfire True Subwoofers' amp, which runs directly off 120 volts, this one works off 12 volts. I won't tell you how it works, but it's cool! In nearly 30 years, you've gone from a coffee -can amp to a cigarette-pack model. Care to sum it all up? To be successful in this industry, you have to have a passion, a real passion for it and a lot of common sense. And some creativity. That helps.

(Audio magazine, 1999)

Also see:

HOME RECORDING FOR THE DIGITAL MILLENNIUM

ABZ's of Stereo FM--Modern Switching-Circuit Decoder

= = = =