by DANIEL KUMIN

This year, the last of the millennium, would be a good time to find some great bargains in analog cassette recorders. It's also an excellent time to save big on dos computers, black-and-white TVs, steam-powered autos, and washboards and mangles.

The hard fact is that for serious home recording, the cassette medium (and analog tape in general) is a "mature technology," which is a polite way of characterizing one whose development curve resembles Francisco Franco's ekg. Today's r&d departments--whether in America, Asia, or Europe--are not spending much on cassette refinements, and even inventor and patent-holder Philips is moving two-footed into digital recording.

Before bidding the cassette adieu, how ever, a tip of the cap: it is nothing short of astonishing just how advanced cassette music recording became in its 25-year life. The medium inherently suffers some potentially crippling flaws, including excessive broadband noise, limited high-frequency dynamic range, trouble some flutter, a tendency to avoid flat frequency response, and substantial noise modulation. And yet, with the application of band-aid upon band-aid, the cassette eventually reached remarkable competence, thanks to the tireless efforts of deck makers (most notably advent, Nakamichi, Teac, and Sony), tape formulators, and Dolby labs.

But the year 2000 indeed signals the start of the digital millennium, and the battle is on to displace the 35-year-old compact cassette in consumers' hearts.

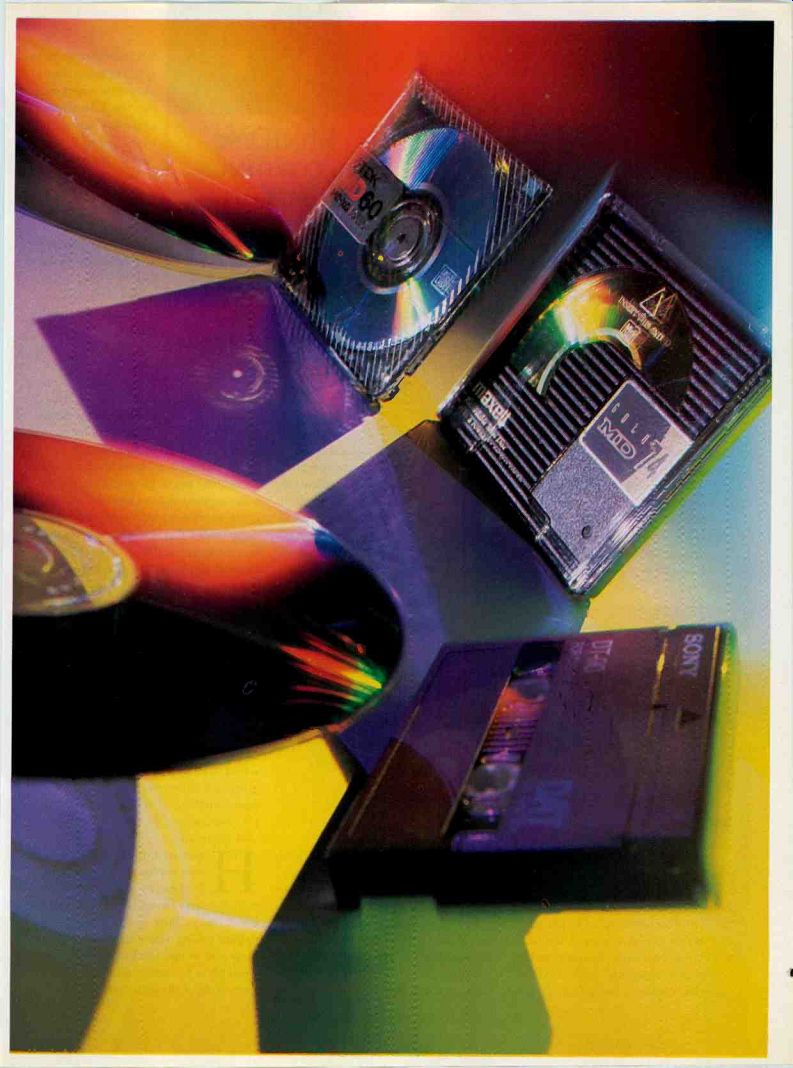

Attentive readers will recall Philips's own contender, the digital compact cassette (DCC), a clever superimposition of digital recording on the cassette's physical dimensions. DCC flared brightly-and briefly-about six years back. Today, the home recordist has three widely accessible digital recording formats at his disposal: minidisc (md), digital audio tape (dat), and two flavors of cd-for mat optical discs-cd-r and cd-rw.

MINIDISC

Sony introduced its MiniDisc con currently with Philips's launch of DCC, but it would be unfair to at tribute the latter's rapid demise to the former's success. The truth is, consumers worldwide (particularly those in the United States) greeted both formats with more or less deafening silence. In the long run, how ever, MD's random-access, optical-disc for mat proved to have the edge. Sony stayed the course, "repositioning" its subcompact magneto-optical system and abandoning its prerecorded MD push in favor of promoting MiniDisc as a recordist-oriented medium, specifically targeting it to cassette users.

A quick Ml) recap: A MiniDisc is about 2 3/8 inches square, with a shuttered case housing a 21-inch disc. The mechanical arrangement resembles a 3 1/2-inch computer disk (another Sony development). Magneto-optical recording exploits laser heat to modify the polarity of a very-high-coercivity magnetic layer; on playback the recorded polarity changes deflect reflected laser light just enough to permit the interpretation of data bits. Recorded MiniDiscs are nearly impervious to everyday magnetic fields, though some anecdotal evidence suggests partial erasure is possible by very strong fields.

A 74-minute audio MiniDisc stores approximately 160 megabytes of data, which reflects its reduction of stereo audio data from CD's 16-hit, pulse-code-modulated (PCM) 1.4 megabits/second to just under 300 kilobits/second, a compression factor just short of 5:1. Sony's proprietary perceptual-coding algorithm, dubbed ATRAC (Adaptive Transform Audio Coding), is in principle similar to Dolby Digital (AC-3) and MPEG-Audio codecs, though different (particularly from MPEG) in its details. In playback, MiniDisc hardware funnels all data through a large memory buffer, from which it is reconstructed and reclocked out as CD-standard 16-bit PCM. Since the disc can thus be read ahead by a comfy margin, MD decks can be made substantially jolt-proof, an attribute that is particularly exploited in the design of portable MD players. This same margin enables MD players and recorders to use random-access data reading and writing to disc. In other words, data is "burnt," or recorded, onto a MiniDisc noncontiguously, as disc space and multisession recording/editing needs dictate. This means that recordings can be extensively edited, divided into multiple tracks, rejoined, deleted, and moved about with terrific freedom.

From the start, Sony has carefully avoided characterizing MD sound as "CD-trans parent." The ATRAC encoder has been through four generations (all fully compatible with all ATRAC decoders) since the for mat's debut in early 1993, and each has de livered audible refinement. First-generation machines were widely agreed to be less-than-sumptuous-sounding, but the latest top-of-the-line MD hardware, which uses ATRAC version 4.5, is another sonic landscape altogether.

Even experienced listeners find the newest flagship MD players and recorders to be very, very close to CD quality on virtually all programs, and audiophiles who dismissed MiniDisc five years ago owe the format another serious listen.

All MD recorders implement the Serial Copy Management System (SCMS), a bit- flag copy-protection scheme that limits dig ital dubbing to a single generation. (SCMS is also required on consumer DAT and CD R/RW machines.) Unfortunately, SCMS doesn't care if that first generation is a dub of a copyrighted CD or of your home-recorded bagpipe concert; you still get only one subsequent pure digital copy. What's more, even digitally dubbing MD does not yield bit-replica copies; an MD deck's S/P DIF digital output delivers reconstructed PCM, not raw ATRAC-encoded data. Copying from MD to MD thus involves ATRAC decoding followed by another round of ATRAC encoding. Consequently, the impact of copying more than a few generations (as you can via the analog inputs) is reported to be substantial. Note that many recent MD machines incorporate sampling-rate converters that enable direct digital dubbing of 48-kHz and even 32-kHz sources, even though the MD format is 44.1 kHz only.

Hardware for MD, both component and portable, is currently produced by at least eight major manufacturers (Sony, Denon, JVC, Kenwood, Onkyo, Pioneer, Sharp, and Yamaha), and pricing is quite aggressive. It's relatively easy to find blank discs at prices of about $5 to $6 each at retail and a mini mum of about $3 each in bulk.

===========

Is Bits Bits?

Bits may be bits, but where and how they are recorded and played can make a big difference.

CD-R and CD-RW technology are living parallel lives: one in the personal computer world and one in consumer electronics.

The underlying technologies are identical, but their applications are anything but.

CD-R/RW combo drives, both internal and external, for personal computers are available from Hewlett-Packard, Ricoh, Yamaha, and others. The combo drives cost about $450; CD-R only variants come at half, or less than half, the price and from many more sources. Various models capable of writing CD D/RWs at twice or four-times normal speed and reading any CD-ROM at 4X, 6X, or even 8X are on the street. All are marketed toward those who need to create CD-ROMs for archiving, distributing, or backing up computer data. But, combined with very affordable CD-mastering PC applications (several are available for Windows and Macintosh), any can also be used for CD-R or CD-RW audio recording, free from the SCMS impediment. In practical terms this requires only a reasonably current I'C with a gigabyte or so of free hard-disk space. Many CD-R/RW drives for PCs can, in fact, dub audio CDs in real time via "pass-through" from a second CD-ROM drive. Doing so, how ever, risks wasting an entire CD-R if, for instance, the process is interrupted by any sort of glitch in the data flow, which might be as seemingly innocuous as a screen-saver or calendar reminder. So most CD burners recommend "premastering" to the hard disk.

The obvious attraction of burning your tunes at your desk instead of in the listening room is the addition of a flexible data drive to the office PC. But there's another equally powerful and far less ethical pull: money.

This Pandora's box opens because CD-R and CD-RW blank discs are sold in two versions: as data discs and as audio discs. There are only two important differences, both of which stem from the Audio Home Recording Act of 1992. First, "audio" discs contain a permanent, pressed-in data header identifying them as such; this must he present for any consumer-model audio CD-R/RW recorder to arm its record mode.

Second, audio blanks also carry a royalty tariff, amounting to 3",, of their wholesale cost. This is distributed among artists and publishers (based on record sales and airplay), under administration by the Library of Congress, as compensation for losses induced by digital copying.

Quick-thinking readers have doubtless surmised the inverse- that data CD-WRW recorders can dub audio CDs onto cheaper "data" blanks-and have posed the obvious question: Once finalized, would these recordings (CD-R for now) play on all audio CD players (home, car, and portable)? The answer is yes.

But doing so would be a clear violation of copyright and, there fore, just plain illegal.

At this writing, audio CD-R blanks cost from $6 to $10 each (depending on the brand, source, and quantity), whereas blank data CD-Rs are routinely available for less than $3 each in any quantity (or, if bought in bulk with manufacturers' rebate coupons, as little as $1 per platter or less). CD-RWs, by comparison, cost about $30 for audio-coded blanks and bottom out at $13 for blank data discs. I will observe without comment that these price discrepancies are far, far, greater than the difference the 3%-of-wholesale Home Recording Act tariff should be expected to exact.

-D.K.

===========

MINIDISC STRENGTHS

Low cost: Recorders are available for less than $300 in both component and portable versions.

Unmatched ergonomics and random access: Track-access speed matches Com pact Disc, with similar options for fast search, random play, and programming.

Highly editable: With a MiniDisc recorder, you can delete, insert, and join or break tracks, in the process recovering any unused disc space. Start and end points are easily trimmed, and you can reorder tracks at no penalty in access speed or smoothness.

Unparalleled portability: A playback buffer gives MD superb jolt-proofing (joggers and sky divers, take note). The combi nation of digital quality and vest-pocket size have made portable MD recorders a popular choice among the live-concert recording/trading set.

MINIDISC WEAKNESSES

Uses data reduction: MD's reliance on ATRAC data reduction means that full transparency is never guaranteed (late-generation models come very close). Data reduction makes generational losses unavoidable, even when you're making digital copies, which in turn makes MD less attractive for serious archiving.

SCMS copy protection can limit dubbing options, even of originals.

Blank discs are considerably more ex pensive than analog cassettes.

Overall, MiniDisc is best suited for dubbing commercial recordings for personal use at home, in portables, and in the car and for making casual live recordings. It is least suited to pro-quality live recording.

DIGITAL AUDIO TAPE

-----Sony's professional PCM-M1 DAT portable has defeatable MS copy protection and records at sampling rates of 48, 44.1, or 32 kHz.

Digital Audio Tape is the finished evolution, circa 1986, of the rotary-head "R-DAT" concept developed by an 81-firm conference spearheaded by CD creators Sony and Philips. In 1981, even as the CD itself debuted, the format was regarded as a recordable companion to the optical digital disc, but nearly a full decade of legal wrangling over copyright and digital dubbing issues ensued. As a result, DAT was largely relegated to pro audio, where it remains an accepted standard for digital mastering and referencing. Although the DAT medium has not changed substantially since its inception, it has benefited from the advances in digital audio technology engendered by CD's great success.

A DAT machine is essentially a marriage between a VCR and a CD player. Its miniaturized, protected cassette, roughly 2 x 3 inches, encases a videotape-like formulation that is 4 millimeters wide. DAT em ploys a rotating helical-scan head, identical in principle to a VCR's, to achieve sufficient writing density. On the playback side, a DAT recorder is very similar to a CD player.

Though data is necessarily formatted differently, DAT's standard-mode digital audio is essentially identical to CD's: 16-bit linear PCM. (At least one manufacturer, Tascam

[Teac], now makes a semipro DAT deck able to record 24-bit PCM.) Of course, DAT decks also require record electronics, metering, and analog-to-digital conversion for their input ends, all of which intensely influence ultimate quality.

There are three official DAT modes.

"Standard" handles 16-bit PCM, just like CD but with a 48-kHz sampling frequency; all DAT decks include this setting. Next, nearly all DAT decks can be set to record (or play) at the CD-standard 44.1-kHz sampling rate instead, permit ting digital dubbing of CDs without requiring sampling-rate conversion. (Pro DAT decks include 44.1 kHz so that studio projects destined for CD can be mastered at the final production sampling rate.) Last, the original DAT specification incorporates an optional, long-play (LP) mode combining 12-bit adaptive PCM (nonlinear coding) with 32-kHz sampling in order to double record time; in this mode, there's a 15-kHz high-frequency limit and a rather modest penalty in dynamic range. A small minority of today's DAT machines offer the LP mode.

Currently, only Sony offers con sumer-targeted DAT hardware, with a solid handful of models that includes several nifty, Walkman-sized portables. On the pro side, however, sever al manufacturers (Fostex, Panasonic, Tascam/Teac, and Sony) produce relatively affordable recorders.

All of the consumer models .include SCMS copy protection (as noted above in the "MiniDisc" section). However, tips on disabling SCMS on a number of DAT models (by simple key sequences or turn-on/key combos) are easily found on the Web, and several semipro models make it easily defeatable.

Blank DAT cassettes have become somewhat more affordable. Available lengths range from 16 to 180 minutes, but pros tend to stick with R-90s or shorter for important work. Bought right, 90-minute DATs will run less than $6 per tape; so-called data-grade DATs can be consider ably cheaper but are not legal for home recording of copyrighted material; that is, you don't pay the home recording royalty when you buy them (see "Is Bits Bits?").

DAT ADVANTAGES

Sound: DAT is CD-transparent or better (at the 48-kHz sampling rate). There is no generational loss; DAT recordings can theoretically be duped (SCMS aside) indefinitely without sonic penalty.

Standardization: DAT is the pro standard, so virtually any studio, broadcaster, or other audio facility will be able to play and record it.

Live recording: DAT is the standard for most live stereo recording, with archival quality available in a number of portable (and even some pocket) models. A number have perfectly usable internal mike preamps (though serious recordists usually bring external mike preamps). Sony makes an external, battery-operated Super Bit Mapping (SBM) add-on for use with its portables, which can deliver near-20-bit resolution at middle frequencies.

===============

Tales from the Pro Side

Despite its current fascination with retro signal processing gizmos and vacuum-tube microphones, the pro audio world is also increasingly digital. A great deal of production mastering takes place on DAT.

True, this work is usually done on professional decks, but aside from their four-digit price tags, confidence heads (an extra set that enables off-the-tape monitoring), and time-code capabilities, not all that much distinguishes these machines from far less costly consumer and semipro models.

Several other pro-oriented digital recording formats are worth noting, however.

Multitrack digital tape recorders have become all but universal, in two basic flavors: Alesis's ADAT format, which uses familiar S-VHS videocassettes, and Tascam's DA-88 family, based on 8-millimeter videotape. Both record eight tracks of 16-bit linear PCM onto affordable, widely available videocassettes, each with CD-standard quality. Of course, eight tracks are six too many for most home recordists interested merely in archiving commercial recordings or in creating casual live-event tapes. But for serious live recordists who routinely use multiple microphones, these machines are a powerful tool, as each feed can be tracked individually for subsequent mixdown, after the heat of the moment.

(And if that's not enough, multiple units of either system may be synched via a simple cable, effectively forming 16-track, 24-track, etc. recorders.) Alesis's second-generation ADAT-XT20 machines even offer 20-bit recording/playback. Equally interesting to leading-edge recordists is Rane's RC24A, a device that permits up to 24-bit digital audio recording to any ADAT deck, using two tape tracks per channel; on playback it can re-dither down to 16-bit PCM for digital mastering destined for CD.

----------The Fostex FD-4 marries an analog mixer to a four-track digital-to-hard-disk recorder. It will perform cut-and-paste editing digitally.

--------- The Fostex DMT8v1 is an eight-track hard-disk recorder combined with an eight-track mixer in one console.

-------The Tascam DA-88 uses an 8mm video mechanism to digitally record eight tracks of 16-bit linear PCM audio

----Akai calls its PS12 a Digital Personal Studio.

It will mix and record 12 tracks of digital audio to a hard disk.

An increasingly popular alternative is a stand-alone, multitrack hard-disk recorder, offered n various types and capacities by Akai, Fostex, Roland, and others. Now available for well under $1,000 and yielding very respectable CD-grade quality, these computer-based disk recorders have a dedicated computer built into a table top, mixer-like console. All permit flexible multitracking and overdubbing, with copy-paste editing, and many include (some as an option) DSP mixing, signal routing, and such effects as reverb, delay, and chorus. These machines are intended more for the multitracking musician/producer of rock/pop music than for real-time recording of live music. All record CD-standard, 16-bit linear PCM except for Roland's HD line of multi-trackers, which use a proprietary data-reduction system. Of course, in all cases recording time is dictated by free hard-disk space and how many tracks "wide" the recording is; all (save the Rolands) run at about 5 megabytes per track per minute.

Sony, Tascam, and Yamaha now all offer briefcase-sized, four-rack "porta-studio"-type multitrack recorders that store data on data-grade MDs, using late-generation ATRAC data reduction. All require more costly blank MD-Data discs (as opposed to ordinary audio MDs) and feature overdub multitracking and mixing. Again, all such models are more appropriate for the project musician/recordist than for live location recording. D.K.

===============

Many semipro models permit disabling of SCMS copy protection for original recordings.

DAT DISADVANTAGES

Compatibility: DAT tapes won't play at your friends' homes (unless they are fellow audio nuts) or on the road (unless you have a DAT portable).

Convenience: Track access and start/end marking can be laborious and are also far slower than on disc-based media such as MD and CD-R/RW.

Longevity: As a magnetic medium, DAT is subject to accidental erasure by stray magnetic fields or damage from exposure to excess heat. (DAT's high-coercivity tape formula is considerably more robust than analog audio tape, however.) The archival life of DAT tapes is unknown, though its powerful error-correction system augurs well. In DAT's 10 years of existence, there have been some reports of block-error-rate (BLER) increases, but the same thing hap pens with manufactured audio CDs, too.

Under sensible storage conditions in the home, a DAT recording's life span is likely to be somewhere between 25 and 100 years.

Blank DATs are relatively costly.

SCMS copy protection can limit dubbing options, even of originals (but see the discussion of pro DATs, above).

Clearly, DAT is great for live recording and least suitable for compilation tapes for car and portable use.

CD-R/CD-RW

-----Philips's CDR 870 records CD-Rs, which play on ordinary CD players, and re-recordable CD-RWs, which currently play only on CD-RW machines.

------ Pioneer's PDR-555RW will record, play, and erase CD-RWs and record and play CD-Rs.

Recordable Compact Discs have long seemed the Holy Grail of home recordists. But be careful what you wish for: Both write-once CD-R and erasable CD-RW have various quirks and limitations that keep them from suiting everybody.

CD-R was developed in the early 1990s for write-once, read-many (WORM) computer CD-ROMs, as codified by the Orange Book II standards. The technology uses one of two organic dyes in place of a manufactured CD's aluminized layer; a very powerful recording laser permanently burns the dye, inducing a color change that affects reflectivity enough to mimic a pressed CD's pits and lands. CD-R reflectivity characteristics are different from those of manufactured CDs, but CD-Rs retain readability and acceptable error rates on virtually all consumer audio (and CD-ROM) players, with the possible exception of a few very early models. Note, however, that few DVD decks (except dual-pickup machines, avail able primarily from Sony and Pioneer) can read CD-Rs because of wavelength incompatibilities. What's more, the documentation accompanying many DVD players warns against playing CD-R/RWs because of unspecified possible damage, but I am unaware of any specific episodes.

CD-R is, to reiterate, a write-once medium: You can record but not erase. Audio CD-R recording, however, is a two-step process, the first being the actual burning of audio data and the second being finalization, the permanent marking of table of contents (TOC) directory data. Audio can be written in multiple sessions, and recorded tracks can subsequently be "deleted" during any session before finalization, at which point their addresses are simply re placed by a permanent auto-skip code (but you do not recover the disc space of such deletions).

CD-RW-Compact Disc-Rewritable was initially called CD-E (CD-Erasable). An elaboration of CD-R technology, CD-RW uses an erasable, phase-change material in place of CD-R's unidirectional dye layer.

The magic layer comprises a crystalline mix of silver, indium, antimony, and tellurium (Merlin would have been proud) with some very particular behavior. When laser-heated to a predetermined temperature (about 900°), it changes to a less reflective, amorphous structure. Applying a somewhat cooler thermal cycle to the same spot changes the material in that region back to crystalline; another high-temp cycle reverts it to amorphous, and so on.

CD-RW discs can be recorded, erased, and overwritten freely, with essentially no limit (a thou sand or more cycles). However, in its CD-audio mode the medium does not permit random access, so in practical terms erasure and rerecording are limited to the last track or to the entire disc. (This is not true, of course, of CD-RW data drives.) There's an other catch: CD-RW discs are significantly less reflective than even CD-Rs and thus are unreadable by virtually all preexisting audio CD players. CD-RWs do play on their native recorders as well as on (projected) new-generation audio CD and CD-ROM players employing multi-read pickups.

(These pickups, designed to comply with the Universal Disc Format standard, are in tended to ensure interoperability between all future CD-R/RW/DVD/ROM players and drives. So far, only Philips and its associated brands have committed to using multiread pickups in their future consumer audio models.) CD-RWs do play on certain, seemingly randomly selected, models of DVD players-but not, paradoxically, the very dual-pickup designs that can play CD-Rs! Confusing, ain't it? Beyond their individual optical-disc specifics and their 16-bit linear PCM, CD-format audio coding, both CD-R and CD-RW recorder/players are functionally identical to DAT recorders.

They have the same virtues and liabilities of various A/D, D/A, and analog audio circuits and topologies.

So far, only three manufacturers have offered consumer recordable-CD hardware (and none of them is Tandy, for all you long-memoried readers). Pioneer offers a selection of CD-R recorder/players in its regular and Elite lines and at least one CD R/RW machine. Philips makes several CD R/RW decks-including a dual-well CD player/CD-R/RW recorder that's tailor made (and actively marketed) for creating "mix" discs (compilations) from prerecord ed CDs; it even has a double-speed dubbing mode. Marantz makes one CD-R/RW deck, the DR700 [reviewed last issue], which is a tweaked-up version of parent Philips's top model. All of the above include the SCMS copy-protection system.

CD-R ASSETS

Finished recordings are playable on virtually any standard CD player-home, car, or portable.

-All stand-alone audio CD-R recorders also function as conventional CD players with any commercial CDs.

Longevity: Despite some recent debate, it appears that with reasonable storage pre cautions, CD-R recordings should outlast similarly archived magnetic media by a significant margin.

CD-R LIABILITIES

CD-R recordings cannot be edited: Any edits made before finalization reduce CD-R capacity, and once a disc is finalized, none are possible.

Before finalization, discs are playable only on CD-R decks.

CD-Rs won't play on most DVD machines, except for dual-pickup models.

The presence of SCMS copy protection prevents second-generation (digital) dubbing, even of original material.

'Blank discs are still relatively expensive (see "Is Bits Bits?") and are not reusable; hence they're not very ecological.

Because no CD-R portable recorders are yet on the market, the format is not convenient for live recording. (Additionally, no current models include internal micro phone preamps.)

MORE CD-RW ASSETS

Blank rewritable discs permit deleting the last track or erasure of a complete disc for rerecording. The discs are reusable.

CD-RWs may play on some DVD decks and should play on DVD-ROM systems.

MORE CD-RW Liabilities

CD-RWs typically will not play on current CD players, only on forthcoming (from Philips) multi-read CD players and on CD/DVD-ROM drives that adhere to the new UDF (Universal Disc Format) pickup requirements. Of course, CD-RWs play on all CD-RW recorders.

Disc erasure is slow; reformatting (required to rerecord a complete disc) can take as long as 30 minutes.

Blank CD-RWs are quite expensive.

CD-R/RWs are appropriate for archiving LP and analog tape collections, archiving and backing up DAT recordings, and compiling "mix" discs of CD tracks. They're least suited to live location recording.

If these three formats don't seem like enough options, just wait a few years.

Solid-state recording is already upon us, in the form of Diamond Multimedia's no-moving-parts MP3 (MPEG-1/Layer-3) player. As the cost of silicon memory be comes ever more like an asymptote to zero, higher-performance options are sure to arise. In the meantime, will traditional home recording survive? Copying LPs to cassettes to preserve them or play them in a car is no longer necessary, and dubbing commercial CDs for these applications makes little sense given that affordable CD players are available for every context. And the cost of the blank tapes or discs is often not far off the price of a second original.

More serious recordists, however, are finding that our wealth of digital options makes for exciting opportunities. It seems probable that anyone with a serious recording bug will eventually end up with at least one machine of each format: a DAT deck for serious live sessions, a MiniDisc portable for casual use and travel (and business dictation), and-sooner or later-a CD-R recorder to make universally playable copies of original recordings.

(Audio magazine, 1999)

Also see:

Departments: FAST FORE-WORD, LETTERS, AUDIO CLINIC, SPECTRUM, MONDO AUDIO, FRONT ROW--GAIN 2: ELECTRIC BOOGALOO

Three Car Radios Tested (July 1976)

= = = =