MANUFACTURER'S SPECIFICATIONS:

Speeds: 15, 7 1/2, and 3 3/4 ips.

Wow and Flutter: Less than 0.08% at 15 ips: 0.10% at 7 1/2 ips; and 0.15% at 3 3/4 ips.

Frequency Response: 30 20,000 Hz ± 2dB at 15 ips; 30-17,000 Hz ± 2dB at 7 1/2 ips, and 40-14,000 Hz ± dB at 3 3/4 ips.

Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Better than 60 dB referred to 0.2% THD, unweighted.

Input Levels: Line, 50 mV to 10 V; Microphone, 300µV to 15 mV.

Output Levels: 2.0 V at 600 ohms; 300 mV at 10,000 ohms.

General Specifications:

Dimensions: 20 1/4 in. W x 17 1/2 in. H x 10 in. D.

Weight: 55 lbs.

Price: $1025, plus $125 for Dolby B, $50 for amps and speakers.

Ferrograph is highly respected not only in England, its country of origin, but it is known all over the world for solid, well-engineered products (what we used to call "built like a battleship"). The original makers of the Ferrograph tape recorder, Wright and Weaire, were established back in the 1920s and I remember buying tuning coils from them in the late 30s. Huge copper can monsters they were, wound with Litz multistrand wire on glass formers, and boasting a fantastic Q-factor.

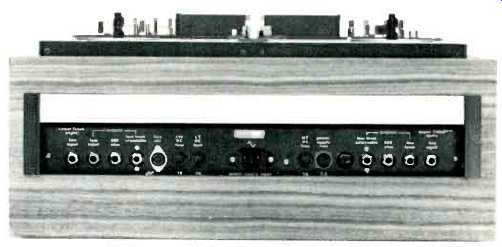

Fig. 1: Socket panel.

Their tape recorders were among the first made in England and the machines' reliability soon made them a first choice for many airports and shipping lines. The Super Seven, then, comes with an impeccable pedigree based on more than 20 years experience. At first glance it looks much like any other semi-professional recorder but there are significant differences, some innovations and, let's face it, some idiosyncrasies. The unit tested has built-in Dolby B and the three speeds are 3 3/4, 7 1/2 and 15 ips. It's also available without the Dolby, or with 1 7/8, 3 3/4, and 7 1/2 ips speeds.

Another option is a pair of built-in 10-watt amplifiers with small loudspeakers mounted on the sides behind grilles.

Styling is neat and workmanlike with the charcoal black center section housing the head assembly contrasting nicely with the satin aluminum panel and controls. Looking at the left, there are two dual-concentric controls, one for Microphone and Line input for channel 1 and the other for Equalization. Then come the two VU meters and in between is a mode switch for selecting upper track, lower track or stereo.

To the right of the second VU meter are two more dual controls, the first a level control (marked Volume), the second is the Microphone and Line input control for channel 2.

At the bottom are Bass and Treble controls for each channel, tape monitor switches, and in the middle are two pushbuttons marked U>L and L>U (more about these later), a Bias switch, a Dolby switch and one for MPX filter. Under the VU meters are preset controls for adjusting the bias which is indicated on the meters by using the bias switch. A nice idea-and it works! That's one of the innovations... . At the left, beside the head assembly, is the tape motion control lever with the functions indicated by Fast, Stop (reset), Pause, and Run. A small locking catch is just above that, and on the right side is a Fast Wind knob and another for reel size, 10 inch and Others. In the center is a large red Record bar switch, a digital counter, and a Reset light. At the top is the three-speed control, and at the very top is a tiny On-Off switch.

The head assembly is exposed by lifting a lid and inside is a retractable lever to facilitate tape loading. Microphone input sockets are in recessed positions at the left and right on the bottom panel, and all the other inputs are located on a recessed panel at the top. (That is, if you operate the machine in the vertical position, otherwise you could say the socket panel is at the rear!) There are three output sockets for each channel, a high impedance at 300 mV, another bypassing the level control, and a 600-ohm output from an emitter follower connected to a point prior to the tone and level controls. Also located on this panel are a.c. power line fuses, d.c. fuses, and a socket for a remote control unit.

Now for some explanations: that Reset light comes on whenever an incorrect setting is made, as for example, if the equalization or speed change knobs are turned when the tape is running. It also operates when the automatic stop is activated. The procedure is to return the tape motion lever to Stop, as the machine will not function when the light is on. Having done that, you then put the controls in the correct positions.

The two push-buttons inscribed U>L and L>U are for track transferring. In other words, the recorded signal from one track can be transferred to a second track. This signal can in turn be transferred to the third or fourth tracks to produce a kind of multi-play recording. As there has to be a small delay between the record and replay signals, it is possible to obtain some echo effects too.

The Fast Wind arrangement is a little unusual as there are two controls. The function lever is turned to Fast and then the Fast Wind knob is rotated left or right to give direction and speed.

An MPX switch cuts the frequency response above 18 kHz so that the 19 kHz FM carrier will not interfere with the Dolby operation. The equalization switch is marked High, Medium and Low, referring to the tape speeds. These are selected by a knob at the top which rotates an indicator disc located behind a window just below. And if you select the wrong equalization for a particular speed, you know what happens! The rest of the controls are conventional enough, although tone controls are rarely found on tape recorders this side of the Atlantic. If you prefer to use the amplifier tone controls, you can disregard those on the recorder or you can use the 600-ohm output sockets. On the other hand, if you play non-standard tapes, the instruction manual gives the correct tone control settings to compensate. By nonstandard, I mean tapes made to other standards such as CCIR and IEC (European).

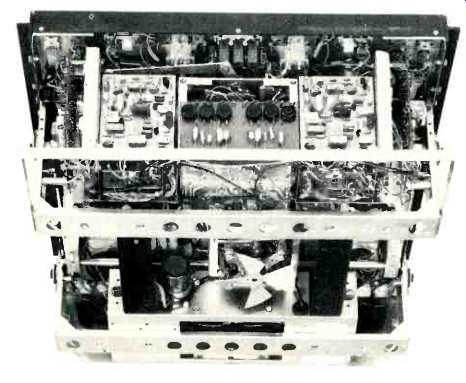

Fig. 2: Interior view.

Three motors are used, one for the capstan drive and two capacitor-start types for the reels. When the switch is set to Fast, these two are connected in series but with the Fast Wind control in parallel so its resistance can be divided between them to produce a rotation in either direction. The capstan motor is a split-phase induction type so its speed is controlled, within certain limits, by the power supply frequency.

Measurements

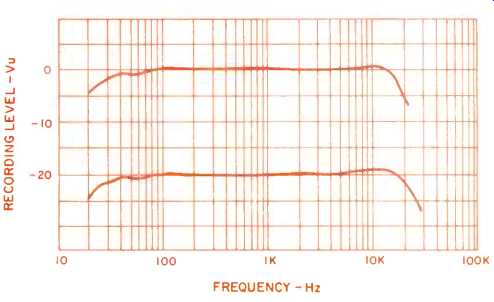

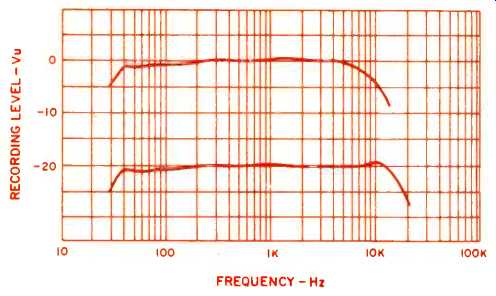

Fig. 3: Record/Play response, 15 ips, Maxell UD-35 tape.

Fig. 4: Record/Play response, 7 1/2 ips.

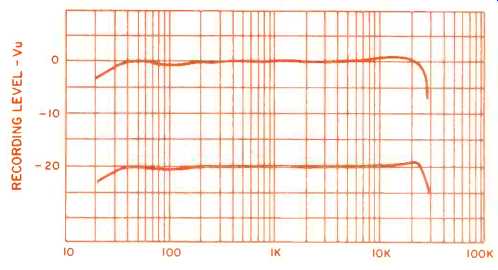

Fig. 5: Record/Play response, 3 3/4 ips.

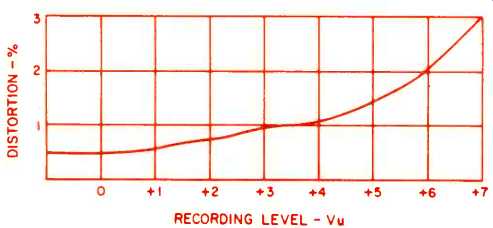

Fig. 6: Distortion versus recording level (1 kHz, 7 1/2 ips).

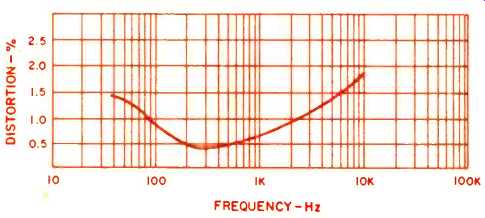

Fig. 7: Distortion versus frequency, 7 1/2 ips, 0 VU.

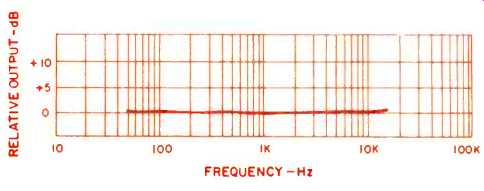

Fig. 8: Playback response with standard test tape, 7 1/2 ips.

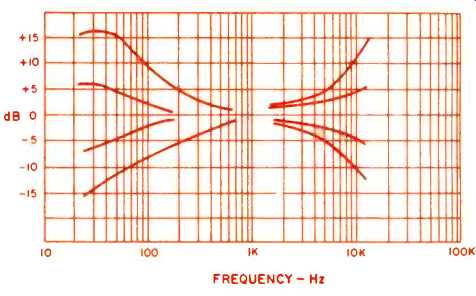

Fig. 9: Tone control characteristics.

Before taking any measurements, the bias was checked by pressing the switch so its value appeared on the VU meters.

According to the instruction manual a setting of 0 VU is suitable for Scotch 203, BASF LGS 35, and similar low-noise tapes and this was found to be the optimum value for the tapes used. Figure 3 shows the Record/Play response with Maxell UD-35 tape at 15 ips and Fig. 4 shows the response at 7 1/2 ips. Results with Scotch Classic tape were very similar.

At 15 ips the 3dB point was 23.5 kHz and at 7 1/2 ips response is down the same at 21 kHz. Tape saturation was slightly less at 15 ips but the effect of saturation can be clearly seen in Fig. 5 which shows the response at 3 3/4 ips. The 3 dB point was 15.5 kHz. Distortion for various recording levels at 7 1/2 ips, 1 kHz is shown in Fig. 6. Note that the 3% distortion level is not reached until + 7 dB, indicating ample recording headroom. Distortion versus frequency can be seen in Fig. 7, and playback response with a standard (Ampex) 7 1/2 ips tape is shown in Fig. 8.

Input required at the line input for 0 record level was 19 mV and 250 µV for microphone. Output levels were measured to be 360 mV at the high impedance output jacks and 1.9 volts at the 600-ohm outputs. Signal-to-noise ratio was 56 dB (ASA weighted) referred to 0 VU, or 63 dB referred to the 3 percent distortion level. Using the Dolby system added another 10 dB, as expected. Wow and flutter measured 0.07 percent at 15 ips, 0.09 percent at 7 1/2 ips, and 0.15 percent at 3 3/4 ips, very satisfactory indeed.

Fast rewind time was 72 seconds for a 1200-ft. reel. Finally, the Dolby system was checked and found to be well within specification, but more about this later.

Listening Tests

For most of the listening tests the Super Seven was teamed up with a Soundcraftsmen PE 2217 preamp and a Phase Linear 400. I must confess it took a little while to get used to some of the controls, specifically the two separate ones for speed change and the two controls for fast rewind (or forward). But I imagine it's like changing from a Detroit Automatic 8 to a Mercedes or Porsche: there's a lot more flexibility. There's that forward-to-reverse rewind facility and the bias adjustment and multitrack switching. All these will score heavily with the serious recording enthusiast. And that reset warning system is really foolproof. At one point in the tests I had set all the controls correctly but the red light still said "no." So I looked again and found that I had not put the tape around one of the tape guides! One question many will ask is this: is the Dolby system really necessary with a machine having such a high standard of performance? Well, there is no doubt whatsoever that the Dolby system is relatively more effective with cassette recorders but even so, the extra 10 dB of noise reduction is worth having. You can use it to get that much more headroom or dynamic range. So the answer is, no, it's not necessary but it does give you more latitude when making recordings. This was confirmed by some recordings made with high quality microphones using the 3 3/4 speed.

Summing up then, the Ferrograph Super Seven is a well-engineered machine with most impressive specifications, all of which were met or exceeded by a comfortable margin. It must certainly be included in that exclusive list of the top four or five recorders made for the exacting home user as well as the professional. Are there any criticisms? Yes, I must say I didn't like the tiny on-off switch, I much prefer a nice large lever type. But of course this is a minor point and I don't suppose everyone would agree!

-George W. Tillett

(Audio magazine, Mar. 1975)

Also see:

Ferrograph RTS-1 Tape Recorder Test Set (Jun. 1972)

Ferrograph Series 7 Tape Deck (Jun. 1970)

Dual Model C 939 Auto-Reverse Cassette Deck (Apr. 1978)--Link |

= = = =