Manufacturer's Specifications:

Frequency Response: 2 Hz to 20 kHz.

Amplitude Linearity: ±0.01 dB, 20 Hz to 20 kHz.

Phase Linearity: ±0.02°, 20 Hz to 20 kHz.

Dynamic Range: 96 dB.

S/N Ratio: 101 dB.

Channel Separation: 100 dB.

THD: 0.0015%.

Output Level: 2.0 V rms.

Number of Programmable Selections: 20 "blocks" (see text).

Storage of "Favorite" Tracks on Discs: 226 discs maximum; 785 "blocks" maximum (see text).

Power Requirements: 120 V a.c., 60 Hz, 20 watts.

Dimensions: 16 9/16 in. W x 3 3/8 in. H x 11.376 in. D (42 cm x 8.6 cm x 30 cm).

Weight: 7.7 lbs. (3.5 kg).

Price: $429.

Company Address: c/o NAP Consumer Electronics, P.O. Box 14810, Knoxville, Tenn. 37914.

It is to Magnavox's credit (or, more properly, to the credit of their parent company, Philips, the co-inventor of the Compact Disc system) that their very first CD players, introduced way back in 1983, employed digital filters and four-times oversampling. While other makers of CD players were employing steep analog output filters and a 44.1-kHz internal clock (one-to-one digital sampling), Philips continued to champion the four-times oversampling approach and the virtues of digital filtering. Gradually, more and more companies switched to oversampling and digital filtration, which is now the accepted standard for all higher quality CD players.

But even as companies have switched to digital filtering, most have opted to use two-times oversampling. Philips, starting CD player production back when reliable 16-bit D/A converters were hard to make, used 14-bit converters in stead, and employed four-times oversampling to make up the difference in resolution. Other companies, starting when true 16-bit D/A converters were fast becoming available, used two-times oversampling. Philips chose to wait until better chips arrived before adopting 16-bit D/A converters-and has retained four-times oversampling even with the new converter chips.

The first unit using this best-of-both-worlds approach that I've had a chance to check out, the Magnavox CDB650, is absolutely superb sounding. Among many other internal circuit refinements, this player employs a special single-chip decoder and error-correction system: The single D/A converter chip actually contains two separate D/A converters, one for each channel, so there is no time delay between channels. There's not much time wasted in getting from one track of a CD to the next, either. The new low-mass laser-pickup assembly has so little inertia that it moves from track to track in 1 sec or less.

While many of the circuit and structural refinements of this player account for its outstanding audible and measured performance, less technically oriented users will be equally enthralled by some of its unique convenience features.

Perhaps the most talked-about new feature is what Magnavox calls FTS (for Favorite Track Selection). This not only lets you program your favorite selections from a disc in any order but also lets you automatically replay those selections, without reprogramming, each time you load that disc again.

The system can memorize over 750 tracks; if you select an average of five tracks per disc, you can store enough information to handle more than 150 discs in this manner! There's no need to tell the player what disc you've loaded, for it "recognizes" each programmed disc's unique digital codes as soon as that disc is inserted. Magnavox does, however, provide a sheet of stick-on numerals that you can affix to the label side of the discs you've programmed into the FTS system; these numbers can be used for reference if you want to change or erase a specific program.

In addition to FTS, the CDB650 has more common programming abilities. Up to 20 selections can be programmed for whatever disc is currently playing. Unlike many CD players, this unit also allows you to program by index numbers (if such numbers have been encoded on your discs).

However, because this requires a bit more memory than programming by track number, you cannot store quite as many index references as tracks. Finally, you can also program the player to start and stop at given times within a track by punching in the times on a keypad; the CDB650 is the first I've ever seen with this capability.

Another handy feature, for those of us who like to copy CDs onto tape (for use in our cars and portable tape players or for creating our own "albums" of selections from more than one disc), is a "Copy Pause" play mode. This interposes 4 S of silence between programmed selections, for the benefit of tape-search systems which use such pauses as markers. Other play modes include "Single" (the player stops after the current track is finished), "Auto Pause" (the player pauses after each track until the "Pause" button is depressed), and "Repeat," which can be used to repeatedly replay a complete disc, a program, or a short section of a track (whose beginning and end have been marked by pressing the "A-43" button).

The Magnavox CDB650 provides three sets of outputs for connection to audio systems. In addition to the normal analog outputs, which provide absolutely flat response, there is a second analog output pair which is filtered to gently roll off the highs above about 10 kHz. Those sensitive listeners who continue to mistake really flat response for "digital harshness," and any others who prefer a bit less high-end response, are free to plug into these extra output jacks if they want to.

Finally, with an eye to the future, the Magnavox CDB650 provides a digital output--handling data as well as sub codes--for applications such as CM-ROM and digital signal processing.

Control Layout

The power switch is to the left of the slide-out disc tray. A large and elaborate display area to the right of the tray indicates track and index numbers, time elapsed on the current track, time remaining on the current track or the entire disc, the current play mode, and whether or not FTS is activated. Below the display area but above the major operating buttons are small, secondary pushbuttons. These select the play and time-display modes, allow you to review and check memorized programs, and activate "Scan" (which automatically plays the beginning of each track on the disc), the repeat-play functions, and FTS.

The numerical keypad, which is used for all programming modes and for direct play of individual tracks without programming, can be tilted out from the right end of the front panel when needed. Other controls for normal programming are on this keypad. After a program is entered here, pressing the "FTS" button stores it in the FTS memory for reuse whenever that disc is played again. The number keys are duplicated on the supplied remote control; this is the first CD player I've run across that offers number keys on both the panel and the remote.

The main operating pushbuttons, along the lower edge of the front panel, are the "Open/Close" switch, "Stop," "Pause," "Play/Replay," forward and reverse "Search," and "Previous" and "Next" track buttons. The search buttons operate at three speeds, depending on how long you hold them down. At first, search is audible and slow enough for you to locate a specific point with 1-S accuracy. If you hold the button down, the search speeds up somewhat but the music remains audible, so this speed can still be used for fairly accurate location of a desired portion of a track.

Finally, if you hold down either search button for about 10 S, the highest search speed is reached. The signal is no longer audible, and you must locate passages by using the time indications on the front-panel display.

A headphone jack and its associated rotary volume control are at the lower right corner of the front panel. The rear panel, in addition to housing the two different pairs of analog output jacks, is equipped with the digital output jack mentioned earlier and with a connector that links the CDB650's remote-control system to that of some other Magnavox components. The power cord for the unit is supplied separately and must be connected to the appropriate receptacle on the rear panel. Two shipping screws must be removed from the underside of the unit before the player will operate properly.

Measurements

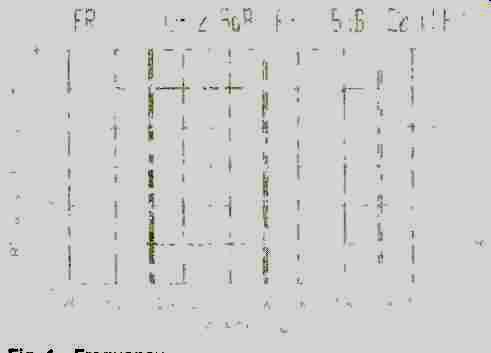

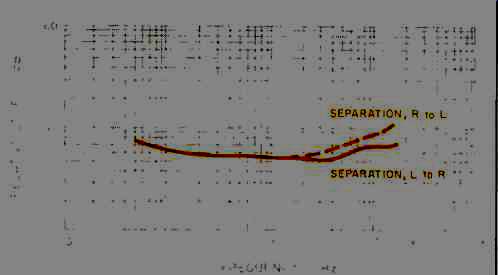

The superior performance made possible by Magnavox's new 16-bit, four-times oversampling technique was obvious from the moment I put the CDB650 on the test bench and began measuring its performance using a new EIA-approved test disc. (This disc, by the way, is now available from CBS Special Products as Test Disc CD-1. [The price for the disc is $45 each plus $3 handling; write to CBS Inc., Columbia Special Products, 8th Floor, 51 West 52nd St., New York, N.Y. 10019.] It has all of the test signals needed for checking out a player in accordance with the soon-to-be-approved EIA Measurement Standards for CD Players.) Frequency response of this player, measured from the normal outputs, was so flat that to present a graph of response curves would have been meaningless. You wouldn't be able to see anything, since the response line would fall on the horizontal calibration line corresponding to "0 dB" for each channel. As nearly as I could determine, response was flat to within less than 0.1 dB over the entire audio range. I was able to plot the player's response when outputs were de rived from the additionally filtered outputs. As you can see in Fig. 1, the effect of these filters is precisely what Magnavox intended it to be: The response through the filtered outputs was down by a bit less than 1.0 dB at 10 kHz and was about 2.5 dB down at 20 kHz.

Fig. 1--Frequency response through left (top) and right (bottom) channels

of filtered output. Response deviations from unfiltered outputs were too

small to be visible.

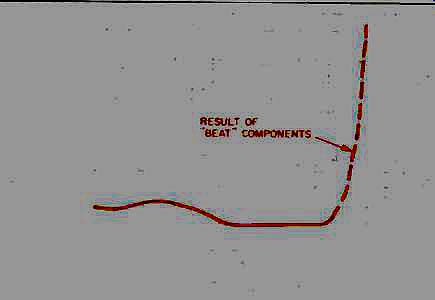

Fig. 2--THD vs. frequency at 0-dB recorded level. Dashed portion of line

shows effect of out-of-band "beat" components

rather than true distortion.

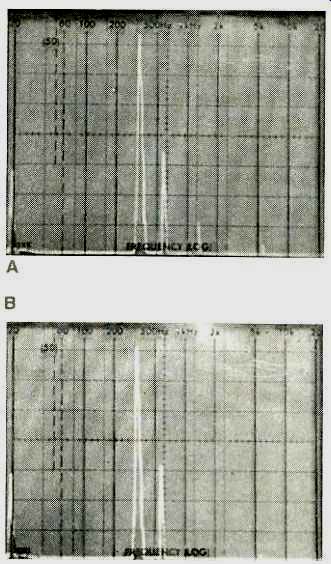

Fig. 3--Spectrum analysis of reproduced 20-kHz test signal from 0 Hz to 50

kHz, measured through unfiltered (A) and filtered (B) outputs (see text).

Harmonic distortion at maximum recorded level was just under 0.002%; more important, it remained at this low, low level over most of the audio range, as shown in Fig. 2. As usual, the dashed line in the region above 10 kHz in Fig. 2 does not represent harmonic distortion. Rather, it arises primarily from the presence of a single inaudible "beat" above the audio band, as seen in Figs. 3A and 3B, which show the spectrum from 0 to 50 kHz. The signal from the "flat" output jacks (Fig. 3A) shows the 20-kHz test signal, the major out-of-band component that almost always appears at around 24.1 kHz in this test, and a couple of low level spurious components in the vicinity of 30 and 40 kHz.

The signal from the filtered outputs (Fig. 3B) shows a very slight roll-off of the 20-kHz test tone and only a slight decrease in the 24.1-kHz out-of-band beat tone. However, those extra components at the still higher out-of-band frequencies are no longer visible within the dynamic range of the spectrum analyzer. Regardless of which outputs were used, the 24.1-kHz major beat was of very low amplitude, especially when compared to poorer quality CD players.

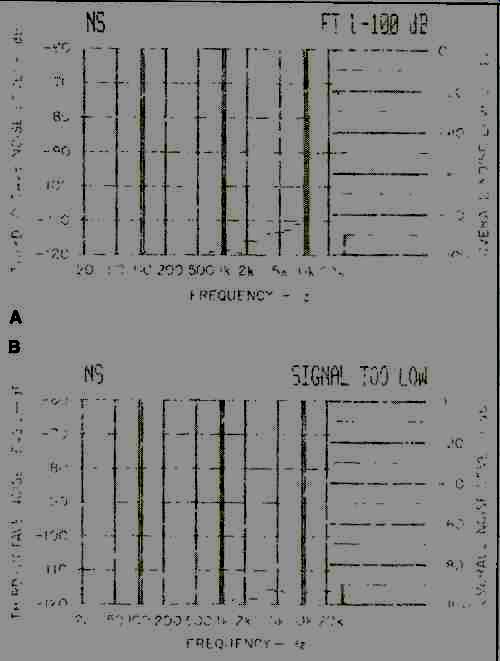

Figures 4A and 4B show the analyses of unweighted and A-weighted signal-to-noise ratios for the CDB650. The unweighted S/N (Fig. 4A) was a very high 100.0 dB (the highest I have ever measured for any CD player). As for A weighted noise, it was simply too low for my test instrument to register; hence the notation "Signal Too Low" in Fig. 4B.

Dynamic range was a never-before-achieved 115 dB! (In CD testing, dynamic range is not synonymous with S/N. The figure for dynamic range is obtained by measuring the difference between maximum [zero] recorded level and the THD amplitude generated by a 1-kHz tone at-60 dB; S/N is the difference between zero level and the noise floor.) Linearity was nearly perfect, all the way from maximum recorded level to-80 dB. De-emphasis, when activated by a disc which had been recorded with pre-emphasis (only a few use this additional noise-reduction technique), was ac curate to within 0.1 dB over the entire audio frequency range. SMPTE-IM distortion measured less than 0.003%, and CCIF IM was even lower, with a reading of 0.002% at maximum recorded level and rising to 0.006% at-10 dB recorded level.

Fig. 4--S/N analysis, both unweighted (A) and A-weighted (B).

Fig. 5--Separation vs. frequency.

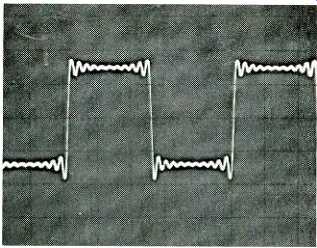

Fig. 6--Reproduction of a 1-kHz square wave.

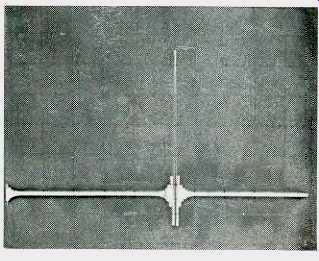

Fig. 7--Single-pulse test.

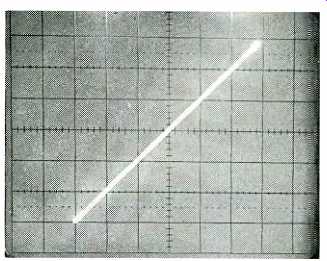

Fig. 8--Interchannel phase comparison at 20 kHz. Absence of interchannel

phase error is indicated by 45° angle of Lissajous pattern on 'scope (see

text).

Stereo separation, plotted as a function of frequency in Fig. 5, was close to 85 dB at mid-frequencies and remained around the 80-dB mark even at 16 kHz, the highest frequency at which this characteristic is measured using the new test disc. Maximum output level from the player was 2.06 V; this level was identical in both channels. Short-term access time (the time it takes the laser pickup to move from one track to the next) was no more than 1 S, and long-term access time (the time it takes to get from an inner to an outer track) measured approximately 3 S.

A 1-kHz square wave, as reproduced by the CDB650, is shown in the 'scope photo of Fig. 6. Like the square waves reproduced by other players that use digital filtering and oversampling, it is close to perfect. The departure from a perfectly flat top in the reproduced waveform is due to the absence of higher order harmonics and not to any ringing or overshoot which might have been present if steep analog low-pass filters had been used. The impulse signal shown in Fig. 7 further confirms the fact that excellent digital filters have been used in this unit.

I am now using a new approach for measuring time delay or phase error between left and right channels: I apply the output of one channel to the horizontal input of a 'scope (the X axis) and the output of the other channel to the vertical input (Y axis). If the signals from both channels are perfectly in-phase, a straight line tilted 45° from lower left to upper right should appear on the screen. As you can see from Fig. 8, that's exactly the result I got when reproducing a 20-kHz signal at the left and right outputs of this CD player.

Use and Listening Tests

When I first put a disc into the CDB650, the display showed the total number of tracks and total playing time.

Other displays were almost self-explanatory, and for those who haven't had much experience using a CD player, the brief but complete owner's manual makes everything clear after a few minutes of reading. After playing some of my favorite discs on this machine, it was clear to me that here was a true state-of-the-digital-art component. Remember the overenthusiastic claim made by Magnavox in 1983: "Perfect Sound Now and Forever"? Well, now the company has come up with a machine that comes very close indeed to realizing that early promise.

Nor is the CDB650 a particularly finicky machine. I subjected it to some rather violent vibrations during some of my listening tests, and it neither muted nor mis-tracked. Disc-drawer action is smooth and precise when loading and unloading discs. Programming and using FTS is simpler than it appears to be when you first read the manual. Once I got the hang of it, I was fascinated by the player's ability to "recognize" the discs I fed to it. Of course, here Philips is simply putting to good use some of the identification data that is part of the standard CD encoding format they helped develop in the first place. Every disc has its own digital identification code; the FTS system stores this code during programming and uses it to select the proper program when that disc is played back. Pretty clever, those microprocessors, aren't they? Some may regard such frills as superfluous, but I don't think that anyone listening to the CDB650 will be able to deny that it is among the best-sounding CD players--if not the outright best sounding one--yet to be produced by any company. And surprisingly, its suggested price belies its quality.

It almost goes without saying that the player was able to handle my special "defects" discs without any mistracking or muting. Once again, I couldn't refrain from digging back for some of my earliest acquired CDs--the ones that I and others had summarily dismissed as being overly strident and harsh-sounding--and replaying them on the CDB650.

A few of the dozen or so discs that fall into this category still were not as musically accurate-sounding as I would have liked, but surprisingly, about three-quarters of them suddenly sounded significantly better. I know that this was not my imagination, since I also played them on an early-generation player that I keep around for just that purpose. The difference is real, and I must attribute the improvement to the digital filtering, the extremely linear 16-bit D/A converters, and the other circuit refinements that have been built into this unit.

It's no secret that small, dedicated audio manufacturers such as Mission, Meridian, and Distech have consistently used early Philips CD players as the starting points for most of their own high-end models, making internal circuit modifications in an effort to achieve better sound. I wonder if that trend will continue and whether some of these manufacturers will now start modifying the CDB650 or its Philips equivalent. Frankly, I think if they do they may be wasting their time. I honestly can't see how they can improve on what the people in The Netherlands have come up with.

-Leonard Feldman

(Adapted from: Audio magazine, Mar. 1987)

Also see:

Magnavox FD1000SL Compact Disc Player (Jun. 1983)

Mission PCM-7000 Compact Disc Player (Aug. 1987)

Onkyo DX-G10 Compact Disc Player (Mar. 1989)

= = = =